Distinguished Churchmen and Phases of Church Work/Alfred Barry

CHAPTER III

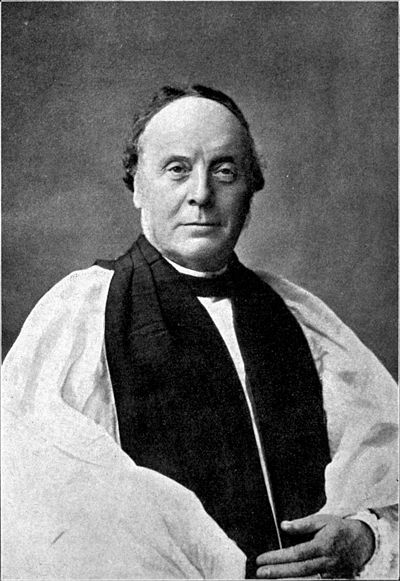

THE RIGHT REV. ALFRED BARRY, D.D.

Formerly Bishop of Sydney, Metropolitan of New South Wales and Primate of Australia.

CHURCH INFLUENCE IN GREATER BRITAIN.

“I say that the real and permanent grandeur of these states must be their religion; otherwise there is no real and permanent grandeur.”

—Walt Whitman.

We live in an age of territoral expansion, and since this policy carries the influence of Great Britain into many lands, few things can afford more interest to the average Briton than the observance of the readiness of fellow-subjects across the seas to adopt the laws, customs and religion of the Mother Country. So entirely is this spirit of emulation abroad that we are brought to speak of “Greater Britain,” knowing full well that much in common obtains throughout the Empire. Of civil and business affairs we are, fortunately, kept well informed through the columns of the daily press, and the achievement of Colonial Federation has been one of the most important events of recent times. But matters religious are less generally known to the world at large, and it is only by such side winds as the return of Bishops and clergy that we become possessed of any definite information in relation to the welfare of the Church and other religious bodies in our colonies. With regard to Australia, it will be admitted that Bishop Barry is eminently fitted to speak, by reason of his five years tenure of the three-fold office of Bishop of Sydney, Metropolitan of New South Wales, and Primate of Australia and Tasmania.

Bishop Barry has had an eventful career, and has served his Church well in numerous capacities. Like his Episcopal brethren, Dr Talbot, of Rochester; Dr Cowie, of Auckland; Dr Jones, of Cape Town; Dr Bickersteth, late of Exeter; Dr Chalmers, of Goulbourn; Dr Blunt, of Hull; Dr Wallis, of Wellington, and several others, he is a native of London, having been born at Ely Place in 1826, the second son of Sir Charles Barry, of architectural fame. His boyhood was for the most part spent in London—after leaving Ely Place, at Langham Place, and, later on, at Westminster, whence he went to King's College. And it seems to have been a very happy boyhood, if one may judge by the incidents which the Bishop himself has recorded in the page devoted to reminiscences of popular religious leaders in the Sunday Companion. In this record the Bishop, after recalling the tolling of the church bell in 1830, in token of the death of King George IV., as the earliest thing within his recollection, describes the rural condition then of many districts now among the most crowded in London and the suburbs. “Travelling was not easy,” he says. “Railways had hardly begun, and we children were taken to see the first out of London—the Greenwich railway—as one of the wonders of the world. London households had to be content in the summer with a change of air in the suburbs—at Blackheath, or Wandsworth, or Putney and the like—and even for this were very much dependent on the old-fashioned stage coaches or the omnibuses, which were just coming into vogue.”

A refreshing little touch of early nineteenth-century London life, surely. But what is more to the point in this work is Bishop Barry's happy sketch of the conditions of Church life at that time. The contrast with those of to-day is indeed marked. In the same account he describes the period intervening between 1826 and 1841 as “a rather dull, prosaic time, socially and politically,” and then goes on to say: “In respect of Church life, it was certainly a dead time, except where parishes and churches were touched and quickened by the influence of the Evangelical revival. In most London churches it was hardly considered to be in good taste to join in the responses or the singing. All this was left to the parish clerk and some Sunday School children in the gallery. Chanting, except in cathedrals, was practically unknown. I can remember when the chanting of the Venite in an ordinary London church was considered an innovation—probably a dangerous innovation. Hymnody was only in its infancy; what was sung was largely from Brady and Tate, or, in some old-fashioned churches, from Sternhold and Hopkins. The sermon, almost always preached in a black gown, was made the all-important matter, as the old “three-decker,” entirely obscuring the east end of the church and the Holy Table itself, very plainly showed. It was generally a written sermon in London churches—rather long and, to young people, mostly tedious. Church architecture and church decoration were at a low ebb, for the Gothic revival and the impulse of church restoration had hardly yet begun. Ministration of the Holy Communion, even in town churches, was infrequent—seldom more than once a month. Confirmations came about once in three years for any district. The cathedrals kept up some tradition of stateliness in service; but there was little vitality about them. I can remember that the whole congregation of St Paul's and the Abbey was easily contained in the choir; the naves lay cold, empty and unused, except at St Paul's for the gathering of the charity school children once a year.” Odd reading this in the present day, but there can be no doubt that it is substantially correct, and that the Bishop has not in the least degree overdrawn the picture. With him “we may well thank God for the revival which He has given us—for the marvellous quickening of spiritual life.”

But let us pursue the Bishop's history further, and in less detail. From King's College, under Bishop Lonsdale, to whom, and to Frederic Denison Maurice, Bishop Barry perhaps owes as much as to any man his early religious bent—he went to Trinity College, Cambridge, where among his contemporaries must have been such men as the late Bishop Westcott, Bishop MacKenzie, and Lord Alwyne Compton, the Bishop of Ely. He did uncommonly well at the University, standing high in the first class of the Classical Tripos, and fourth among the Wranglers in the same year (1848) as the senior Wranglership fell to Todhunter. A fellowship of his college was the proper reward. In due course he proceeded to the M.A., B.D. and D.D. degrees, and on later dates the D.C.L. was conferred on him by the Universities of both Oxford and Durham. He was ordained Deacon at Ely, and Priest at Oxford, the latter in 1853. Subsequently he went the tutorial way of many Bishops—Dr Tait, Dr Benson and Dr Temple, to wit—and became successively Sub-Warden of Trinity College, Glenalmond; Headmaster of Leeds Grammar School; and Principal of Cheltenham College. Then came the more strictly clerical experience. For four years he was Examining Chaplain to the Bishop of Bath and Wells, and for ten years Canon of Worcester, during five of which he was also Hon. Chaplain-in-Ordinary to the Queen, and for three, Boyle Lecturer. Moreover, for fifteen years, commencing in 1868, he was Principal of his old London College (King's). In 1879 he had progressed from the honorary position to that of Chaplain-in-Ordinary to the Queen, and continued so to serve her late Majesty when, in 1881, he migrated from Worcester to a Canonry at Westminster. Three years later he was consecrated by the Archbishop of Canterbury Lord Bishop of Sydney, Metropolitan of New South Wales, and Primate of Australia, with jurisdiction over something like 8,000 square miles. On Bishop Barry's return to Great Britain, in 1889, he became assistant Bishop in the Diocese of Rochester, Bampton Lecturer at Oxford, and Hulsean at Cambridge. In 1891 he was appointed Canon of Windsor, and in 1895 Rector of St James', Piccadilly. Under Dr Temple he occasionally rendered Episcopal assistance; but Bishop Barry's commission as assistant Bishop of London really issued from Dr Creighton, and in 1900 he retired from the Rectory of St James' in order to take up more work in the metropolis. Notwithstanding his very active participation in the affairs of the Church in the general sense, Bishop Barry has found time and opportunities for furthering her interests with his pen, among his many publications being The Teacher's Prayer Book, Side Lights of Science on Faith, Notes on the Gospels and the Catechism, The Ecclesiastical Expansion of England, etc., besides several volumes of sermons. From his college days onwards he has been a zealous supporter of the cause of Religious Education, and in the seventies he brought his ripe experience into practical use as a member of the London School Board.

In London Bishop Barry is well known both in the pulpit and out, and his services are much appreciated. In times like the present, when at the Round Table Conference there is undeniable proof of many parties in the Church—Extreme Ritualists, High, Broad, Evangelical and moderate Churchmen—it is difficult to gauge precisely the particular school to which an individual belongs. In this, as in many other cases, the prelate or clergyman is keeper of his own conscience, and therefore the best judge, but with regard to Bishop Barry it is quite safe to assert that he has never posed as an extreme man, one way or the other, and that he has consistently followed after the things that make for peace and goodwill among men.

Complying with a request for an interview, Bishop Barry told a most interesting story in relation to the Church in Australia.

“The earliest British settlement in Australia,” his lordship observed, “was in 1788, when the first batch of convicts was landed there; and, strangely enough, the Government of the day had made no provision whatever for the spiritual care of either the convicts or the soldiers who guarded them. It is almost incredible, but it is true, that only just before the expedition started could Mr Wilberforce and the Bishop of London induce the Government to allow the Rev. R. Johnson—an English clergyman who volunteered for the purpose—to accompany the party, not with any official authority, but simply by permission; and to him is due, humanly speaking, under very great difficulties, and with little encouragement, the foundation of the Church of England in Australia. The work was carried on by the voluntary effort of certain English clergy (aided by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel at home); among whom may be named the Rev. Samuel Marsden, who was afterwards the apostle of New Zealand, and the Rev. William Cowper, and others. By degrees the civil authorities began to recognise and support the work, congregations were formed and churches built; and in 1829 there was an attempt made to organise the Church under Archdeacon Broughton, who, whimsically enough, was called the Archdeacon of Calcutta—Calcutta being about 6,000 miles away! Afterwards, in 1836, he was consecrated as the first Bishop of Australia; and from that time Church advance was rapid and steady. As years rolled on new Bishoprics were created, and the Church organisation followed up the extension of Colonial Settlement.

“The Synodical Government of the Church in Australia and, in fact of the Colonial Churches generally, was brought about in the year 1850, when six Bishops met at Sydney under the presidency of Bishop Broughton. The Church in Australia is now completely organised as to government; it has its Diocesan Synods meeting annually, its Provincial Synods meeting every three years, where the Dioceses are formed into provinces, and every five years its General Synod, embracing the whole of Australia and Tasmania. There are now in Australia as many as sixteen Bishoprics, viz., Sydney, Goulburn, Bathurst, Newcastle, Grafton and Armidale, and Riverina—these forming the province of New South Wales; Melbourne, Ballarat and Tasmania, in the south-east; the three Bishoprics in the north—Brisbane, North Queensland and Rockhampton; Adelaide, in South Australia; and Perth, in Western Australia. Recently there have been created two which may be called missionary Bishoprics—one in Carpentaria, on the mainland, and one in New Guinea. Under these sixteen Bishoprics there are now, at least, 1,200 clergy, and, roughly speaking, the Church population must be between one and a half millions and two millions.

“In 1872 it was arranged that the Bishop of Sydney should become Primate of the whole of Australia and Tasmania, so that, curiously enough, Colonial Federation, which has only recently been secured in civil matters, was long ago accomplished in the ecclesiastical sphere. In all the government of the Church it should be observed that representatives of the clergy and representatives of the laity are co-ordinated under the presidency of the Bishops, and no Canon of the Church, either Diocesan or general, is carried without the consent of both clergy and laity and the sanction of the Bishop, or Bishops, as the case may be. It may be noted also that the election of the Bishop is made by the Diocesan Synods.

“As to the constitution of the Church, it is to be observed, in the first place, that by a free act of their own the Synods have determined not to depart in essential doctrine, worship or discipline from the Church at home. In other things they are entirely independent. The work of the Church in Australia for our English people only differs from the work at home in the fact that it requires continually to expand, in the geographical sense, in order to follow the expansion of the population. Every year new parishes are being formed and new missions established. The great difficulty is the sparseness of population in newly-settled country, there being many so-called parishes which are really missionary circuits, perhaps 200 miles round. As the country is still mainly pastoral, the population is very scattered, and there is in consequence great difficulty in providing for it—a difficulty which it would be impossible to cope with except by the very free use of lay agency.

“Besides, however, the regular work of the Church in Australia for our English people—and it may be remembered that of all the colonies Australia is the most predominantly British in character—there has to be undertaken some distinctly missionary work among the subject races. First, among the remnant of the aborigines, now chiefly found in Queensland and Western Australia, for whom provision is made by the Civil Authority, and, as far as possible, by Church missions also; next, among the Chinese immigrants, found in most of the colonies, but especially in the northern part of Australia. There are missions to the Chinese in several Dioceses, and by these Chinese congregations have been formed, and Chinese converts have been ordained. In Sydney, for instance, near Botany, there is a very flourishing Chinese church, to which I myself ordained the first Chinese clergyman of our own Church. It may be noted that the influence of these missions for good over the Chinese population extends far beyond the circle of actual conversion.

“Then, again, in Queensland there is at present a population consisting of those commonly, but improperly, called Kanakas, who have been brought from the islands of the Pacific for work in the semi-tropical or tropical plantations. A good deal has been done to Christianise them in Queensland, in connection with the Melanesian Mission in the Pacific Islands. Next comes the Melanesian Mission itself, founded by the great Bishop Selwyn, afterwards ennobled by the martyrdom of his successor, Bishop Patteson, and subsequently nobly served by Bishop John Selwyn, the son of the founder. Its principal object is to educate and convert native boys and youths, and then to send them out as missionaries to their own countrymen—as Bishop Selwyn said, ‘to float the black net by a few white corks.’ And this effort, which has its centre at Norfolk Island, is now one of the most successful of English missions, and is mainly supported by the Church in Australia and New Zealand, although it still receives help from at home.

“Lastly, there is the mission to New Guinea, founded and directed by the Board of Missions appointed by the General Synod of the Church in Australia. This mission was begun some fifteen years ago, while I was Primate of Australia, and a Bishop has been recently consecrated to superintend its work.

“The Church in Australia, it will be seen, affords an illustration of the important fact that every Colonial Church has a double function—first, to care for our own English people; and, next, to serve as a new centre of missionary expansion.

“In its earlier stages, the Church in Australia was supported by the State, and, subsequently, that State support was divided between it and certain other of the greater English religious communions. All support has now been withdrawn, and the Church has but very slight endowment. The effect of the want of endowment is to render the clergy more dependent upon their congregations, and also to make it difficult to maintain works of Church extension, of which the immediate necessity may not be apparent. But it is due to Australian Churchmen to say that, speaking generally, there is liberal support of religious ministrations, and that the standard of contribution for Church purposes annually is considerably higher than in England. At the same time, as I have already indicated, lay agency and co-operation are freely forthcoming, and are absolutely indispensable for the maintenance of any effective religious influence.

“One great difficulty in the way of Christianity in Australia is, of course, the existence of religious divisions. Indeed, the evil of such divisions is perhaps even more felt, owing to the need of continual expansion and the occupation of new districts, than is the case in the more settled condition of Christianity in the old country. Outside the Church of England the chief religious bodies are the Roman Catholic, almost entirely Irish in its composition; the Presbyterian, largely Scottish, and especially powerful in Victoria; the Wesleyan and the Congregational. There are, of course, other religious Communions, but of little influence compared with these. The difficulty created is painfully visible when we visit some little outlying settlement, and see there the co-existence of rival Churches and places of worship where there is only sufficient need and resource for one.”

“To what extent, my lord, are laymen allowed to assist in the ministrations of the Church?”

“Their scope of service is very considerable. In Sydney, for instance, we had two Orders of Lay-readers. The members of one placed their services unreservedly at the disposal of the Bishop, to go, as far as possible, wherever they were needed; and the members of the other Order were called Local Lay-readers, and undertook duty only in the parish or neighbourhood with which they were connected. When I tell you that, even in Sydney, which was a comparatively settled Diocese, there was one parish so-called, where the clergyman, otherwise single-handed, had no less than twelve places at which he had to minister, you will easily see that, without the free use of lay agency, the maintenance of even occasional services would have been impossible. Accordingly, lay-readers are allowed to do almost everything, except to celebrate the Holy Communion and to pronounce the Absolution. Of course, as far as possible, they work under the direction of the clergy, and always under the authority of the Bishop. They are mostly gratuitous helpers. Expenses, of course, are paid; and in some few instances there is a moderate stipend.”

“What is the strength of the Church in comparison with that of the other denominations combined?”

“It is difficult to tell. I should say, however, that the Church of England is far the most powerful body. In New South Wales it includes about 45 per cent, of the population; the proportion may be somewhat less in other Colonies. I found that the Primate of the English Church was practically considered as the leader (always provided he did not assume leadership), by all the denominations except the Roman Catholics, who were very bitterly hostile. But one effect of the absence of Establishment in Australia is that at public and national functions there is no minister of religion who would naturally, and, as a matter of course, occupy a representative position, and on this matter difficulties have often arisen.”

“What is the position as regards education?’

“With regard to education the systems of the different Colonies vary considerably. But education is always undertaken and maintained by the Government, voluntary schools not being forbidden, but receiving no Government support. I may note that these voluntary schools are mainly found in the Roman Catholic body; and their position is rather a curious one; for the Government allow attendance at these voluntary schools to be substituted for attendance at the public schools, and yet take no pains whatever to inspect them or to ascertain their efficiency. In New South Wales it is laid down in the Public School Act that ‘secular education’—by which, I suppose, is meant education for the work of this life—is impossible without ‘general religious instruction,’ and, accordingly, such general instruction ought to be given, and in some considerable degree is given, by the teachers of the schools. I should say, from my own experience, that this general instruction would be as systematic and as effective as that given under the London School Board, if it were not for the opposition of the Roman Catholics, who, on this matter, from wholly different motives, may be said to join hands with the Secularist party. Besides this provision, the New South Wales Act allows authorised religious instructors to enter the public schools under proper arrangement during school hours, and to give unfettered Church instruction to children of members of their own Church and indeed of any other religious denomination, if the parents choose that it should be so. This provision was largely taken advantage of by our Church. In the Sydney Diocese in my time—and, I have no doubt, it is so still—we had many thousands of children under clerical and lay instructors—the expense being, of course, borne by the Church itself. As a rule, the other religious Communions did very little in this direction. Had they done more, no doubt greater difficulties of arrangement would have existed. In other Colonies the system of education was generally secular, although facilities for voluntary religious instruction, mostly out of school hours, were generally given. I must add that the effect of that secular system upon religious knowledge and upon character was most injurious, as the Bishop of Manchester has shown in relation to Victoria.”

“What of the parties in the Church in Australia?”

“I should say that the High Church influence is less in Australia than in England. The ecclesiastical position, however, varies considerably in various Colonies. In New South Wales the Roman Catholic population in my time was considerable, and generally voted solid on all subjects, religious or secular. The result was the creation on the other side of what we should call here a strong Orange party in things secular, and this reacted in some degree upon things ecclesiastical.”

Going more into detail, the Bishop spoke of the important work undertaken by the Temperance and Purity Societies in the Church, and of efforts like those put forth by the Church Army at home, for the special benefit of people whom it is desirable to raise in the social scale. Nonconformists wishing to become ordained, and giving proof of proper qualifications, are, it transpired, freely admitted to the service of the Church. The Bishop made it clear that Colonial Dioceses differ very much in character. In a Diocese like Sydney, for instance, the religious exigencies are very different from those of the newer and more rural Dioceses. The life of the country clergyman in Australia often requires great power to bear physical hardship. Large tracts of country have to be covered, generally on horseback, and the almost complete impossibility of getting domestic servants throws additional and heavy responsibilities on him, and still more on the wife and ladies of his family. On the other hand, in the great towns the life and work of the clergy are much the same as in England. The pressure of what is called the “voluntary system” on the rank and file of the clergy is great, because of their comparatively dependent position; and, as a consequence, young men, with their natural love for independence, are somewhat slow to take Holy Orders. Although probably the average income of the clergy in the Diocese of Sydney in Bishop Barry's time was quite up to the average of English Dioceses, there were very few men of independent means in the ranks of the clergy, and the disadvantage of this condition of things may be better understood, when regard is had to the number of livings attached to the Church at home which could not possibly be worked but for the readiness of men with private means to serve them. In Australia, the outlying parishes are generally helped from a Central Church Fund, and in that case the appointments are made by the Bishop. But where parishes are independent and self-supporting they can, if they like, have what is termed a Board of Nominators, partly parochial and partly appointed by the Synod, who can select and present to the Bishop.

Notwithstanding the many difficulties which have to be overcome, Bishop Barry regards the prospects of the Church in Australia as very hopeful. When he left, the average Church contribution in the Diocese of Sydney alone amounted to about £80,000 per annum. This, no doubt, has increased since, and will go on increasing, and the many interesting phases of the work may be confidently expected to yield still happier results.

The work of the Colonial Churches for the Evangelisation of the world may not have about it the romance, so to speak, of what is generally known as missionary work. But it is at least as important and effective; its solidarity with the work of the Church at home is more obvious, and, caring as it does both for our own people, “the children of the Dispersion,” and for the heathen races within the sphere of their influence, it is, perhaps, the means of the most natural and solid progress of the Kingdom of God.