English Caricaturists and Graphic Humourists of the Nineteenth Century/Chapter 17

although the design was his, not one line of the etchings which bear his name are due to the artist's point.[1]

The father of Robert William was an engraver and enameller, and under his directions he acquired a knowledge of this technical branch of art; but evincing a taste and preference for drawing and painting, he became a pupil of George Clint, A.R.A., under whose direction he studied subject and portrait painting. He painted fifteen theatrical portraits for Mr. Cumberland in illustration of his "British Drama," and a collection of these works was afterwards exhibited at that melancholy monument to past exhibitions, the Colosseum in the Regent's Park. He was employed by Charles Knight in the illustrations to his "Shakespeare," "London," "Old England," "Chaucer," and the now forgotten "Penny Magazine," for all of which publications he executed many designs on wood.

It must not be supposed because Robert William Buss was not considered the right man to illustrate "Pickwick," that he was therefore an indifferent draughtsman. His finest book etchings are probably those which he executed for Harrison Ainsworth's novel of "The Court of James II."; but in a higher and far more ambitious walk in art he was not only more successful, but achieved in his time a considerable reputation. Among his pictures may be mentioned one of Christmas in the Olden Time, which, apart from its merits as a painting, showed that he possessed considerable antiquarian knowledge. Other works of his are, The Frosty Morning, purchased by Lord Charles Townshend; The Stingy Traveller, bought by the Duchess of St. Albans; The Wooden Walls of Old England, the property of Lord Coventry; Soliciting a Vote, and Chairing the Member; The Musical Bore; The Frosty Reception; Master's Out; Time and Tide Wait for no Man; Shirking the Plate The First of September; The Introduction of Tobacco; The Biter Bit; The Romance; and Satisfaction. For Mr. Hogarth, of the Haymarket, he painted four small subjects illustrative of Christmas, entitled, The Waits; Bringing in the Boar's Head; The Yule Log, and The Wassail Bowl; all afterwards engraved. For Mr. James Haywood, M.P., he executed a series of drawings illustrative of student life at Oxford, Cambridge, Durham, London, and Paris; while two vast subjects, The Origin of Music and The Triumph of Music (each twenty feet wide by nine feet high), were painted for the Earl of Hardwick, and are, or lately were, in the music saloon at Wimpole, in Cambridgeshire. His pictures were seventy-one in number, twenty-five of which were engraved. On the whole, therefore, Robert William Buss might afford to bear the refusal of Charles Dickens's patronage with equanimity.

The paintings and etchings of Robert William Buss evince a strong leaning in the direction of comic art, a taste which prompted him, in 1853, to deliver at various towns in the United Kingdom a course of very successful and interesting lectures on caricature and graphic satire, illustrated by several hundred examples executed by himself. In 1874, the year before his death, he published for the amusement of his friends, and for private circulation only, the substance of these lectures, under the title of "English Graphic Satire and its Relation to Different Styles of Painting, Sculpture, and Engraving." The numerous illustrations to this work were those drawn for his lectures by the artist, and reproduced for his book by the process of photo-lithography. So far as comic art and caricaturists of the nineteenth century are concerned, the author has comparatively little to say; but the work is valuable as regards the subject generally, and might have been published with advantage to the public. The artist delivered also lectures on "The Beautiful and the Picturesque," as well as on "Fresco Painting."

Mr. Buss, if not very original as a comic designer, possessed nevertheless a keen sense of humour. One of his pictures (engraved by H. Rolls), entitled Time and Tide Wait for no Man, represents an artist, sketching by the sea-shore, so absorbed in the contemplation of nature that he remains unconscious of the fast inflowing tide, and deaf to the warnings of the fisherman who is seen hailing him from the beach. ****** The comic publications which either preceded or ran side by side with Punch had for the most part a somewhat short and unsatisfactory career. Perhaps the most successful of them was Figaro in London, 1831-36, which we have already noticed. The Wag, a long forgotten publication, enjoyed a very transient existence. In 1832 appeared Punchinello, on the pages of which Isaac Robert Cruikshank was engaged. Punchinello, however, ceased running after its tenth number. Asmodeus in London, notwithstanding the support it derived from Seymour's pencil, was by no means a commercial success. The Devil in London was a little more fortunate. This periodical commenced running on the 29th of February, 1832, and the illustrations of Isaac Robert Cruikshank and Kenny Meadows enabled it to reach its thirty-seventh number. Tom Dibdin's Penny Trumpet ignominiously blew itself out after the fourth number. The Schoolmaster at Home, notwithstanding Seymour's graphic exertions, collapsed at its sixth number. The Whig Dresser, illustrated by Heath, enjoyed an existence exactly of twelve numbers. The Squib (1842) lasted for thirty weeks before it exploded and went out. Puck (1848), illustrated by W. Hine, Kenny Meadows, and Gilbert, died the twenty-fifth week after its first publication. Chat ran its course in 1850 and 1851. The Man in the Moon, under the literary guidance of Shirley Brooks, Albert Smith, G. A. Sala, and the Brothers Brough, enjoyed a comparatively glorious career of two years and a half. Diogenes (started in 1853, under the literary conduct of Watts Phillips, the Broughs, Halliday, and Angus Bethune Reach), notwithstanding the graphic help rendered by McConnell[2] and Charles H. Bennett, gave up the ghost in 1854. Punchinello (second of the name) flickered and went out at the seventh number. Judy (the predecessor of the present paper) appeared 1st February, 1843, but soon died a natural death. Town Talk, edited by Halliday and illustrated by McConnell, lasted a very limited time. London, started by George Augustus Sala in rivalry of Punch, soon ceased running; while the Puppet Show, notwithstanding the ability of Mr. Procter, enjoyed but a very brief and transitory existence. The strong and healthy constitution of Punch enabled him not only to outlive all these, but even a publication superior in some important respects to himself. We allude to the Tomahawk, whose cartoons are certainly the most powerful and outspoken satires which have appeared since the days of Gillray.[3]

Among the draughtsmen whom Punch called in to help him in his early days was a useful and ingenious artist, inferior in many respects to Kenny Meadows, his name was Alfred Henry Forrester, better known to most of us under his nom de guerre of "Alfred Crowquill." The scribes of the "Catnach," or Seven Dials school, of literature are satirized by Forrester (in the second volume), wherein we see a "Literary Gentleman" hard at work at his vocation of a scribe of cheap and deleterious literature, consulting his authorities—"The Annals of Crime," a "Last Dying Speech and Confession," and the "Newgate Calendar." In The Footman we have a gorgeous figure, adorned with epaulets, lace, and a cocked hat, reading (of all things in the world) the "Loves of the Angels," over a bottle of hock and soda-water! The Pursuit of Matrimony under Difficulties is a more ambitious performance. "Punch's Guide to the Watering Places" (vol. iii.) is illustrated with a number of coarsely executed cuts, wholly destitute of merit; the fourth volume contains a cartoon entitled Private Opinions. But the graphic humour of Alfred Crowquill, although amusing and sometimes bright and sparkling, was unsuited to the requirements of a periodical such as Punch. As better men came forward, he gradually dropped out of its pages, and we see nothing more of him after the fourth volume.

Alfred Crowquill was a sort of "general utility" man, essaying the character of a littérateur as well as that of an artist, and achieving as a natural consequence no permanent success in either. In his literary capacity, Alfred Henry Forrester made his first appearance (we believe) in "The Hive," and "The Mirror," under the editorship

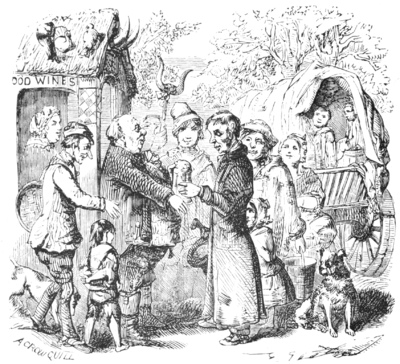

Alfred Crowquill.][From "The Book of Days."

"SWEARING THE HORNS" AT HIGHGATE.

"When any person passed through Highgate for the first time on his way to London, he, being brought before the horns, had a mock oath administered to him, to the effect that he would never drink small beer when he could get strong, unless he liked it better; that he would never eat brown bread when he could get white, or water-gruel, when he could command turtle-soup; that he would never make love to the maid when he might to the mistress; and so on . according to the wit of the imposer of the oath, and simplicity of the oath-taker."

[Face p. 369.

In these days a man like Forrester would be almost at a discount, but at the time when he started there was less competition, and a useful, clever man, like he undoubtedly was, was fortunately not lost. His hands, in fact, were always full, and a list of some of the books to which his pen and his pencil contributed will be found in the Appendix. One of the best of his designs was a title-page he executed for a work published by Kent & Co., under the title of "Merry Pictures by the Comic Hands of Alfred Crowquill, Doyle, Meadows, Hine, and Others" (1857), a réchauffage of cuts and illustrations which had previously done duty for books of an ephemeral character, such as "The Gent," "The Ballet Girl," and even of the superior order of "Gavarni in London."[4] Some excellent designs executed by him on wood will be found in Messrs. Chambers' "Book of Days." In his dual character of a writer and comic artist, Crowquill was an inveterate punster. Leaves from his "Memorandum Book" (1834) will give us a good idea of his style. In "Tea Leaves for Breakfast," Strong Black is represented by a sturdy negro carrying a heavy basket; a tall youth with a small father personating Hyson; a housemaid shaking a hall mat, to the discomfort of herself and the passers-by, is labelled Fine dust; a cockney accidentally discharging his fowling-piece does duty for Gunpowder; while Mixed is aptly personified by a curious group of masqueraders. The vowels put in a comical appearance: A with his hands behind him listens to E, who points to I as the subject of his remarks, which must be of a scandalous character, as the injured vowel looks the picture of anger and astonishment. E finds a ready listener in O, who opens his mouth and extends his hands in real or simulated amazement and horror.

Crowquill was a clever caricaturist, and began work when he was only eighteen. We have seen some able satires of his executed between the years 1823 and 1826 inclusive. One of the best, published by S. Knight in 1825, is entitled, Paternal Pride: "Dear Doctor, don't you think my little Billy is like me?" "The very picture of you in every feature!" Ups and Downs (Knights, 1823), comprise "Take Up" (a Bow Street runner); "Speak Up" (a barrister); "Hang Up" (a hangman); "Let-em-Down" (a coachman); "Knock-em-Down" (an auctioneer); "Screw-em-Down" (an undertaker). The following are given as Four Specimens of the Reading Public (Fairburn, 1826): "Romancing Molly," "Sir Lacey Luscious," a "Political Dustman," and "French à la Mode." Two, in which he was assisted by George Cruikshank, entitled, Indigestion, and Jealousy, will be found in the volume published (and republished) under the name of "Cruikshankiana." The latter shows on the face of it that, while Crowquill was responsible for the design, the etching and a large share of the invention are due to Cruikshank.

If not a genius, the man was talented and clever,—a universal favourite. He could draw, he could write; he was an admirable vocalist, setting the table in a roar with his medley of songs. Even as a painter he was favourably known. Temperance and Intemperance were engraved from his painting in oils, and called forth a letter of

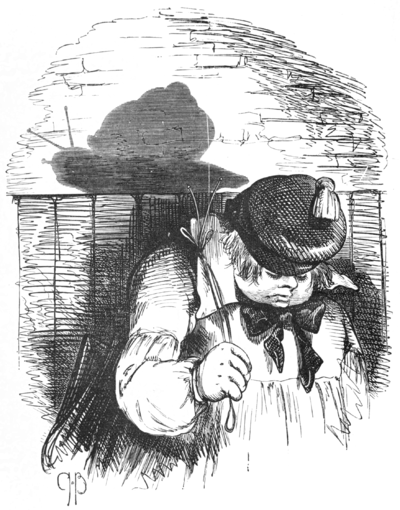

Chas. H. Bennett.]["Shadows and Substance."

. . . creeping like a snail

Unwillingly to school."—As You Like It.

[Face p. 371.

****** Some of our readers may possibly remember seeing in one of the comic publications published concurrently with or shortly after the appearance of Mr. Charles Darwin's work, a series of comical designs ridiculing the theory of the "origin of species" in a manner which must have astonished as well as amused the learned philosopher. The origin of the genus footman, and of the dish he carries to his master's table, is traced out as follows: The dish carries a bone, which eventually finds its way into the jaws of a mongrel cur with a peculiarly short tail. The process then goes merrily onwards; the dog gradually develops; his skin turns into a suit of livery with buttons, the dog-collar gradually assumes the form of a footman's tie, until the process is ended and the species complete. In like manner, a cat develops into a spinster aunt; a monkey into a mischievous urchin; a pig into a gourmand; a sheep into a country bumpkin; a weasel into a lawyer; a dancing bear into a garrotter; a shark into a money-lender; a snail into the schoolboy to which Shakespeare likens him; a fish into a toper, and so on. These "developments" (twenty in number), which were dedicated to Mr. Darwin, are signed "C. H. B," and these are the initials of Charles H. Bennett, one of the gentlest, most promising; and withal most original graphic humourists of the century.

Amongst the earliest of the serials which he illustrated was, we believe, Diogenes, a sort of rival of Punch, which made its appearance and ran a brief course in 1853-4. Associated with him in the illustrations were McConnell and Watts Phillips, the latter of whom contributed largely also to the literary matter. We find a clever design of his (in Leech's style) in the second volume: "Now, gentlemen of the jury," says a brazen-faced barrister, "I throw myself upon your impartial judgment as husbands and fathers, and I confidently ask, Does the prisoner [the most murderous-looking ruffian un-hung] look like a man who would knock down and trample upon the wife of his bosom? Gentlemen, I have done!"

There was considerable originality in the designs of Bennett, which is more particularly manifested in the well-known series of humorous sketches in which the effect intended to be produced is effected by means of the shadows of the figures represented, which are supposed to indicate their distinguishing failings and characteristics. Among them may be mentioned a tipsy woman amused at the shadow cast by her own figure of a gin bottle; an undertaker, in his garb of woe wrung from the pockets of widows and orphans, casts the appropriate shadow of a crocodile; a red-nosed old hospital nurse of a tea-pot; a worn-out seamstress of a skeleton; a mischievous street boy of a monkey; an angry wife sitting up for a truant husband of an extinguisher; a tall, conceited-looking parson, with a long coat, of a pump; while a sweep, with his "machine," to his mortal terror beholds his own shadow preceding him in the guise of Beelzebub himself. The series is continued in a work published by W. Kent & Co. in 1860, under the title of "Shadow and Substance," the letterpress of which is contributed to Bennett's pictures by Robert B. Brough. Literary work of this description, like William Combe's "Doctor Syntax," is necessarily unsatisfactory; but the pictures themselves are distinctly inferior to the series which preceded them, the best being Old Enough to Know Better,—a bald-headed, superannuated old sinner behind the scenes, presenting a bouquet to a ballet girl, his figure casting a shadow on the back of the scene of a bearded, long- eared, horned old goat.

We are in no position to give a detailed list of Charles Bennett's work, which was of a very miscellaneous kind, comprising among others a series of slight outline portraits of members of parliament, which appeared in the Illustrated Times, an edition of the "Pilgrim's Progress," edited by the Rev. Charles Kingsley; "John Todd," a work by the Rev. John Allen; "Shadows," and "Shadow and Substance," just spoken of; "Proverbs, with Pictures by Charles H. Bennett," etc., etc. His talent at last attracted the notice of the weekly Punch council, and he received the coveted distinction of being engaged on the permanent staff of that periodical.His life, however, was a brief one. The diary of Shirley Brooks, who took much personal interest in him, refers 'with some anxiety to his illness on the 3oth of March, 1867. On the 3ist of March the report was somewhat more favourable; but the 2nd of April brought a letter from the editor of Punch, Mark Lemon, which said that Charles Bennett had died between the hours of eight and nine o'clock that morning. "I am very sorry," adds Shirley Brooks in an autograph note appended beneath the letter referred to. "B[ennett] was a man whom one could not help loving for his gentleness, and a wonderful artist." The obituary notice by the same hand which appears in Punch records that "he was a very able colleague, a very dear friend. None of our fellow-workers," it continues, "ever entered more heartily into his work, or laboured with more earnestness to promote our general purpose. His facile execution and singular subtilty of fancy were, we hoped, destined to enrich these pages for many a year. It has been willed otherwise, and we lament the loss of a comrade of invaluable skill, and the death of one of the kindliest and gentlest of our associates, the power of whose hand was equalled by the goodness of his heart." Charles Bennett was only thirty-seven when he died.

He left a widow and eight children unprovided for, for his health having precluded it, no life insurance had been effected. The Punch men, however, with the unselfishness which so nobly characterizes them, put their shoulders to the wheel for the family of their stricken comrade. "We shall have to do something," said Shirley Brooks in his diary of the 3rd of April; and they did it accordingly. A committee was immediately started, on which we find the names of Messrs. Arthur Lewis,[5] Wilbert Beale, Mark Lemon, Du Maurier, John Tenniel, Arthur Sullivan, and W. H. Bradbury. Then came rehearsals, and, on the 11th of May, a performance at the Adelphi in aid of the Bennett fund. Mr. Arthur Sullivan had, in conjunction with Mr. F. C. Burnand, converted the well-known farce of "Box and Cox" into an operetta of the most ludicrous description. This was the opening piece—the forerunner of "Pinafore," "Pirates," "Patience," and other triumphs. Arthur Sullivan himself conducted, and the players were Mr. Du Maurier, Mr. Quinton, and Mr. Arthur Blunt. Then followed "A Sheep in Wolf's Clothing," in which Mesdames Kate Terry, Florence Terry, Mrs. Stoker, Mrs. Watts (the present Ellen Terry), and Messrs. Mark Lemon, Tom Taylor, Tenniel, Burnand, Silver, Pritchett, and Horace Mayhew took part. This was succeeded by Offenbach's "Blind Beggars," who were admirably personated by Mr. Du Maurier and Mr. Harold Power. The evening concluded with a number of part songs and madrigals sung by the Moray Minstrels—so called from their chiefly performing at Moray Lodge, the residence of Mr. Arthur Lewis. Between the two portions of their entertainment, Shirley Brooks came on and delivered an address written by himself, which contained the following allusion to him for whose family the generous work had been undertaken:—

"Only some friends of a lost friend, whose name

Is all the inheritance his children claim

(Save memory of his goodness), think it due

To make some brief acknowledgment to you.

Brief but not cold; some thanks that you have come

And helped us to secure that saddened home,

Where eight young mourners round a mother weep

A fond and dear loved father's sleep.

Take it from us—and with this word we end

All sad allusion to our parted friend—

That for a better purpose generous hearts

Ne'er prompted liberal hands to do their parts.

You knew his power, his satire keen but fair,

And the rich fancy, served by skill as rare.

You did not know, except some friendly few,

That he was earnest, gentle, patient, true.

A better soldier doth life's battle lack,

And he has died with harness on his back."

The last verse alludes to Kate Terry's approaching marriage:—

"Last, but not least, in your dear love and ours,

There is a head we'd crown with all our flowers.

Our kindest thanks to her whose smallest grace

Is the bewitchment of her fair young facé.

Our own Kate Terry comes, to show how much

The truest art does with the lightest touch.

Make much of her while still before your eyes—

A star may glide away to other skies."

By this performance, a second which took place at Manchester on the 29th of July, and the efforts of Shirley Brooks and the members of the committee, a large sum was raised. ****** The Punch volumes, prior to his withdrawal from its pages, are interspersed with numerous mirth-provoking drawings on wood by the late Mr. Thackeray. Probably the best of these will be found in the "Novels by Eminent Hands," in one of which (in amusing burlesque of Phiz's spirited title-page to "Charles O'Malley") we see the hero flying over the heads of the French army. Charles Lever was nervously sensitive to ridicule, and, although he laughed at and enjoyed the clever jeux d'esprit in which "Phil Fogarty," "Harry Jolly-cur," "Harry Rollicker," etc., put in their respective appearances, he declared nevertheless, with evident vexation, that he himself might just as well retire from business altogether. This, indeed, he proceeded to do; and although we miss from that time the rattling heroes of the Frank Webber and Charles O'Malley school, we are indebted to Thackeray for the striking proof which Charles Lever was thus enabled to afford us of the versatility of a genius which enabled him to change front and alter his style with manifest advantage to his literary reputation.

The fact of his waiting upon Dickens at his chambers in Furnival's Inn "with two or three drawings in his hand, which strange to say he did not find suitable" for "Pickwick," has been told so often that there is no occasion for repeating it again; but the circumstances under which he seems to have sought the interview not being, so far as we know, stated anywhere, we shall now proceed to relate them, Thackeray was in London when Seymour shot himself in 1836. The death of the latter caused a vacancy in the post of illustrator to "Figaro in London," which at that time Seymour was illustrating as well as "Pickwick," and such vacancy was supplied by Thackeray, who, I think, continued to illustrate it until the paper died a natural death. His designs for "Figaro in London" were drawn in pen and ink on paper, and transferred to the wood by the engravers, Messrs. Branstone and Wright, and the remuneration he received for them was very trifling, at most a few shillings each. It was probably this circumstance which put into his head the idea of illustrating "Pickwick." From what we know of the graphic abilities of Thackeray and the fastidious requirements of Dickens, we may readily understand why the post rendered vacant by Seymour's suicide was given to an abler artist.

We wish that from a work dealing with comic art in the nineteenth century the name of Mr. Thackeray might be omitted; for no notice of him, however short, would be just or complete which failed to refer to his book illustrations. To do this we must separate Thackeray the artist from Thackeray the man of letters. Regarding him simply in the character of illustrator of the novels of W. M. Thackeray, we are bound in justice to the memory of that great and sterling humourist, to say that he has undertaken a task which is manifestly beyond his powers. While Thackeray with his pen could most effectively describe a fascinating woman, like Becky Sharp, the illusion vanishes the moment his artist essays to draw her portrait with his pencil. While Thackeray's women are pretty and fascinating, well dressed and accomplished, the artist's women on the contrary are hideous; their waists commence somewhere in the region of their knees; and their clothes look as if they had been piled on their back with a pitchfork. The same remarks apply to the men; while the originals are witty or clever, handsome or well-dressed, those presented to us by the artist are destitute of calf, and their limbs so curiously constructed that the free use of them as nature intended would be a matter of utter impossibility. Those defects are the more noticeable because the artist has shown in his admirable essays on George Cruikshank and John Leech how thoroughly he was alive to the possession of artistic genius in others.

The admiration which we have for Thackeray the man of letters, and the way in which we have already expressed that admiration, render it unlikely that the drift of these remarks will be misunderstood. While rejoicing that the admirable tales and satires of the humourist are uninjured by illustrations which are altogether unworthy of them, we venture to suggest how much better the result might have been had the latter been entrusted, as in the case of "The Newcomes," to other hands, and the artist contented himself with the initial letters and designs on wood with which his writings are pleasantly interspersed. We have seen it somewhere stated (we think in the volume entitled "Thackerayana") that the author's rapid facility of sketching was the one great impediment to his attainment of excellence in illustrative art. Some of his designs indeed bear on their face evidence of the rapidity with which they were thrown off; but no satisfactory explanation appears to be possible of his contempt for what Mr. Hodder has termed the "practical laws which regulate the academic exercise of the pictorial art," and his apparent ignorance of the art of balancing his figures so as to enable them to stand upright, to walk straight, or to move their limbs with the grace and freedom assigned to them by nature. One of the designs to "The Virginians" shows a horseman, who in the letterpress is described as crossing a bridge at full gallop, whereas in the picture both man and horse will inevitably leap over the parapet into the river below. Nothing could possibly avert the catastrophe, and the effect thus produced is due, not to the manifest carelessness and haste with which the sketch is thrown off, but to a palpable defect in the artistic powers of the designer himself. Yet in the face of defects so patent and so palpable we have found it gravely stated, " The world which is loth to admit high excellence in more than one direction, has never fitly recognised Thackeray's great gift as a comic draftsman. Here [i.e. in a work edited by his daughter] he will be found advantageously represented; inferior, it is true to the unjustly neglected Hablot Browne ('Phiz'), but often equalling if not sometimes surpassing the greatly over-rated John Leech."

Ay! "the world is loth to admit high excellence in more than one direction," and experience has taught it that few men, however gifted, are capable of exercising two different arts with an equal measure of success. Thackeray was both a genius and an artist, but the world has long recognised the fact that the former manifested itself only when he laid down the pencil and took up the pen. If called on to prove his incapacity to illustrate his own work, we will refer the reader to his admirable novel of "Vanity Fair." The time selected for the story is the early part of the present century; and on the plea that he had "not the heart to disfigure his heroes and heroines" by the correct but "hideous" costumes of the period, Thackeray has actually habited these men and women of 1815 in the dress of 1848! Cruikshank, Leech, "Phiz," or Doyle, it is unnecessary to say, would have been guiltless of such an absurdity; and the difficulty in which the gifted author found himself, and the confession of his inability to cope with it, afford the clearest possible evidence of his utter incapacity to illustrate the story itself. If any further proof be wanted, look at the designs themselves. Captain Dobbin would be laughed out of any European military service; such a guardsman as Rawdon Crawley could find no place in her Majesty's guards; "Jemima" (at p. 7), "Miss Sharp in the schoolroom" (p. 80), the children waiting on Miss Crawley (p. 89), the figures in the fencing scene (p. 207), "The Family Party at Brighton," "Gloriana" trying her fascinations on the major, "Jos" (at p. 569), and "Becky's second appearance as Clytemnestra," without meaning to be so, are caricatures pure and simple; and yet these are  | |

| "GRUFFANUFF." | |

|

|

| "PRINCE BULBO SEIZED BY THE GUARDS." | "MONKS OF THE SEVEREST ORDER OF FLAGELLANTS." |

SKETCHES BY THACKERAY FROM HIS "ROSE AND THE RING." [Back to p. 378. | |

And yet, in justice to the great humourist of the nineteenth century, let us hear what another great writer has to say upon the very illustrations which seem to us to call for such severe animadversion. After telling us that Thackeray studied drawing at Paris, affecting especially Bonnington (the young English artist who died in 1828), Mr. Anthony Trollope goes on to say, "He never learned to draw,—perhaps never could have learned. That he was idle and did not do his best, we may take for granted. He was always idle, and only on some occasions, when the spirit moved him thoroughly, did he do his best even in after life. But with drawing—or rather without it—he did wonderfully well, even when he did his worst He did illustrate his own books, and every one knows how incorrect were his delineations. But as illustrations they were excellent. How often have I wished that characters of my creating might be sketched as faultily, if with the same appreciation of the intended purpose. Let any one look at the 'plates,' as they are called, in 'Vanity Fair,' and compare each with the scenes and the characters intended to be displayed, and then see whether the artist—if we may call him so—has not managed to convey in the picture the exact feeling which he has described in the text. I have a little sketch of his, in which a cannon-ball is supposed to have just carried off the head of an aide-de-camp,—messenger I had perhaps better say, lest I might affront military feelings,—who is kneeling on the field of battle and delivering a despatch to Marlborough on horseback. The graceful ease with which the duke receives the message though the messenger's head be gone, and the soldierlike precision with which the headless hero finishes his last effort of military obedience, may not have been portrayed with well-drawn figures, but no finished illustration ever told its story better."[6] We read these remarks with profound astonishment, and can only ask in reply: If, as Mr. Trollope has admitted, Thackeray "never learned to draw,—perhaps never could have learned," how he could manage "to convey" in any of his pictures "the exact feeling he has described in the text"?—how, in the face of the admitted incorrectness of "his delineations," he could be in any way fitted to illustrate a novel of such transcendent excellence as "Vanity Fair"?

It has been assumed, without any sort of authority, that it was only when Thackeray found he could not succeed as an artist that he turned to literature. The statement is altogether unwarranted. At or about the very time he was engaged in drawing the cuts for "Figaro in London," he was—if we are to judge of the sketch of "the Fraserians" in the "Maclise Portrait Gallery," in which young Thackeray may easily be recognised—writing for "Fraser's Magazine." Be this, however, as it may, it seems tolerably certain that the rebuff he received from Dickens had no hand in turning him into the path of letters, towards which his genius and unerring judgment alone most fortunately guided him.

- ↑ See Mr. Alfred G. Buss, in "Notes and Queries," April 24th, 1875.

- ↑ A very clever and promising artist, who died early, of consumption.

- ↑ As the Tomahawk appeared in 1867, it does not come within the scope of the present work.

- ↑ A work produced by David Bogue, in 1849, and illustrated by the celebrated French caricaturist, which professes to give sketches of "London Life and Character." Allowing for the unfaithfulness of the portraits, which are wholly Parisian, these designs possess unquestionable merit. The literary contributors were Albert Smith, Shirley Brooks, Angus B. Reach, Oxenford, J. Hannay, Sterling Coyne, and others

- ↑ Afterwards married Kate Terry.

- ↑ "Thackeray," by Anthony Trollope, in "English Men of Letters," p. 7.