Eskimo Life/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III

THE 'KAIAK' AND ITS APPURTENANCES

A superficial examination of certain details in the outward life of the Eskimo might easily lead to the erroneous conclusion that he stands at a low grade of civilisation. When we take the trouble to look a little more closely at him, we soon see him in another light.

Many people nowadays are vastly impressed with the greatness of our age, with all the inventions and the progress of which we daily hear, and which appear indisputably to exalt the highly-gifted white race far over all others. These people would learn much by paying close attention to the development of the Eskimos, and to the tools and inventions by aid of which they obtain the necessaries of life among natural surroundings which place such pitifully small means at their disposal.

Picture a people placed upon a coast so desert and inhospitable as that of Greenland, cut off from the outer world, without iron, without firearms, without any resources except those provided by Nature upon the spot. These consist solely of stone, a little drift-wood, skins, and bone; but in order to obtain the latter they must first kill the animals from which to take them. We, in their place, would inevitably go to the wall, if we did not get help from home; but the Eskimo not only manages to live, but lives in contentment and happiness, while intercourse with the rest of the world has, to him, meant nothing but ruin.

In order that the reader may realise more vividly upon what an accumulation of experiences the civilisation of this people rests, I shall try to give a sketch of the way in which we must conceive it to have arisen.

Let us, then, assume that the ancestors of the Eskimos, according to Dr. Rink's opinion, lived in long bygone ages somewhere in the interior of Alaska. They must at all events have been inlanders somewhere and at some time, either in America or in Asia. Besides being hunters upon land, these Eskimos must also have gone a-fishing upon the lakes and rivers in birch-bark canoes, as the inland Eskimos of Alaska and the Indians of the North-West do to this day. In course of time, however, some of these inland Eskimos must either have been allured by the riches of the sea or must have been pressed upon by hostile and more warlike Indian tribes, so that they must have migrated in their canoes down the river-courses toward the western and northern coasts. The nearer they drew to the sea, the more scanty became the supply of wood, and they had to hit upon some other material than birch-bark with which to cover their canoes. It is not at all improbable that before leaving the rivers they had made experiments with the skins of aquatic animals; for we still see examples of this among several Indian tribes.

It was not, however, until the Eskimo encountered the rough sea at the mouths of the rivers that he thought of giving his boat a deck, and at last of closing it in entirely and joining his own skin-jacket to it so that the whole became watertight. The kaiak was now complete. But even these inventions, which seem so simple and straightforward now that we see them perfected—what huge strides of progress must they not have meant in their day, and how much labour and how many failures must they not have cost!

Arrived at the sea-coast, these Eskimos of the past soon discovered that their existence depended almost entirely upon the capture of seals. To this, then, they directed all their cunning, and the kaiak

guided them to the discovery of the many remarkable and admirable seal-hunting instruments, which they brought to higher and ever-higher perfection, and which prove, indeed, in the most striking fashion, what ingenious animals many of us human beings really are.The bow and arrow, which they used on land, they could not handle in their constrained position in the kaiak; therefore, they had to fall back upon throwing-weapons.

The idea of these, too, they borrowed from America, making use in the first instance of the Indian darts with steering-feathers, which they had themselves used in hunting upon land. Small harpoons or javelins of this sort are still in use among Eskimos of the southern part of the west coast of Alaska.

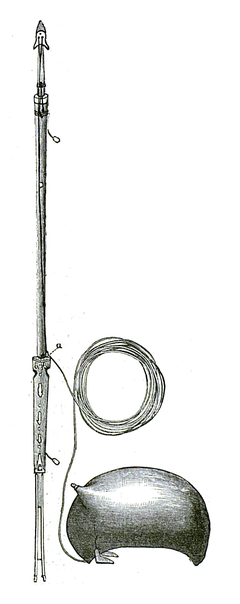

As one passes northward along this coast, however, the feathers soon disappear, and are replaced by a little bladder fastened to the shaft of the javelin. This device has been found necessary in order to prevent the harpooned seals from diving and swimming. Further, it has been found necessary so to arrange the point of the javelin that it cannot be broken by the seal's violent efforts to get rid of it, but detaches itself instead (at c on accompanying engraving) and remains hanging to a line (from c to b) fastened (atb 1) to the middle of the javelin shaft, which is thus made to take a transverse posiposition, and still further to impede the movements of the seal when it rushes away with it. Such was the origin of the so-called bladder-dart, known to all Eskimo tribes who live by the sea.

The bladder is made of a seagull's or cormorant's gullet, inflated and dried. It is fastened to the javelin-shaft by means of a piece of bone with a hole bored through it for the purpose of blowing up the bladder. This hole is closed with a little wooden plug.

From this bladder-dart the Eskimo's principal hunting-weapon—the ingenious harpoon with bladder and line—has probably developed. In order to cope with the larger marine animals, the size of the bladder was doubtless gradually increased; but the disadvantage of this—the fact that it offered too much resistance to the air to be thrown far and with force—must soon have been felt. The bladder was then separated from the javelin, and only attached to its point by means of a long and strong line, the harpoon-line. The harpoon, which was now made larger and heavier than the original javelin, was henceforward thrown by itself, but drawing the line after it. The bladder, fastened to the other end of the line, remained in the kaiak until the animal had been pierced, when it was thrown overboard.

This harpoon, with all its ingenuity of structure, ranks, along with the kaiak, as the highest achievement of the Eskimo mind.[1]

Its shaft is made in Greenland of red drift-wood—a sort of fir from Siberia, drifted by the polar current across the Polar Sea—which is heavier than the white drift-wood used in making smaller and lighter projectiles. The upper end of the shaft is fitted with a thick and strong plate of bone, on the top of which is fixed a long bone foreshaft—commonly made of walrus or narwhal tusk—which is fastened to the shaft by means of a joint of thongs, so that a strong pressure or blow from the side, instead of shattering the foreshaft, causes it to break off at the joint. This foreshaft fits exactly into a hole in the harpoon-head proper, which is made of bone, generally of walrus or narwhal tusk. It is now always provided with a point, or rather a sharp blade, of iron; in earlier days they used flint or simply bone. The harpoon-head is fastened to the harpoon-line by means of a hole bored through it, and is provided with barbs or hooks so that it sticks fast wherever it penetrates. It is, moreover, so adjusted that it works itself transversely into the flesh as the wounded seal tugs at the line. It is attached to the harpoon-shaft by being fitted to the before-mentioned foreshaft, whereupon the line is hooked on to a peg, placed some distance up the harpoon-shaft (at a), by means of a perforated piece of bone fixed at the proper distance. Thus the head and the shaft are held firmly together.

When the harpoon strikes and the seal begins to plunge, the bone foreshaft instantly breaks off at the joint (see illustration), and the harpoon-head, with the line attached to it, is thus loosened from the shaft, which floats up to the surface and is picked up by its owner, while the seal dashes away, dragging the line and bladder after it. It must be admitted, I think, that it is difficult to conceive a more ingenious appliance, composed of such materials as bone, sealskin, and drift-wood; and we may be sure that it has cost the labour of many generations.

Two forms of this harpoon are in use in Greenland. The one is called unâk; its butt-end is finished off with nothing more than a bone knob, and it is longer and slighter than the other. This is called ernangnak, and has at its butt-end two flanges or wings of bone, now commonly made of whale-rib, designed to increase the weight of the harpoon and to guide it through the air. It is one of these which is represented on p. 36.[2]

At Godthaab the ernangnak was most in use; but I heard old hunters complaining that, in a wind, it was more difficult to throw than the unâk, since a side gust was apt to take too strong hold of the bone flanges and to make the harpoon twist.

The harpoon line is made of the hide either of the bearded seal (Phoca barbata) or of the young walrus. It is generally from 15 to 18 yards long, and a good quarter of an inch (about 7 millimetres) thick.

For the bladder they use the hide of a young ringed seal (Phoca fœtida). The skin is slipped off, as nearly as possible whole, the hair is removed, the apertures at the head, the fore limbs, and the hind limbs are tied up so as to be air-tight, and the whole is dried.

The line is coiled upon the kaiak-stand, which is fixed in front of the man. It serves to keep the coil well above the sea, which is always washing over the deck; and thus the line is always ready to run out without fouling when the harpoon is thrown.

The harpooned seal is killed by means of a lance (anguvigak). This consists of a wooden shaft (commonly made of the light white drift-wood, in order that it may carry well), a long bone foreshaft, and an iron-bladed tip. In former days flint was used instead of iron. The foreshaft is generally made of reindeer horn or else of narwhal tusk. In order that the seal may not break it off, it is fastened to the shaft by a joint similar to that which fastens the foreshaft to the harpoon.

The Eskimos have also the so called bird-dart (nufit). Its shaft is likewise of white drift-wood. Its point consists of a long narrow spike, now made of iron, but in earlier times of bone; and besides this there are fastened to the middle of the shaft three forward-slanting spikes, made of reindeer-horn and provided with large barbs. The idea is that if the end of the dart does not pierce the bird, the shaft shall glide along it, and one of these outstanding spikes must strike and penetrate it; and it is thus, in fact, that the bird is generally brought down. Another invention, this, which no one need blush to own.

All these projectiles can, as I have shown above, be traced back to the Indian feather dart.

But in order to throw their weapons further and with greater force, the Eskimos have invented an appliance which distinguishes them from all surrounding races, whether American or Asiatic. This invention is the throwing-stick. Oddly enough, this admirable device, which by its sling-like action greatly augments the length and strength of the arm, is known in very few parts of the world—probably only in three. It is found in Australia in a very primitive form, among the Conibos and Purus on the Upper Amazon, where it is scarcely more developed than in Australia, and finally among the Eskimos, where it has reached its highest perfection.[3] We can scarcely

conjecture that the throwing-stick, appearing in places so remote from each other, springs from any common origin, and we must thus accept the Eskimo form of it as an original invention of that particular race. It is generally made in Greenland of red drift-wood, and is about half a yard long (fourteen sticks in my possession range from 42 to 52 centimetres in length). At its lower and broader end it is about 3 inches (7 or 8 centimetres) in width, and is flat, with a thickness of rather more than half an inch (about 11⁄2 centimetre). The sides, at the lower and broader end, have indentations in them for convenience in grasping—on one side for the thumb, on the other for the fore-finger; while on the upper flat side there runs a long groove along the whole length of the stick, to receive the dart or harpoon.[4] The throwing-stick is found in two forms. The one is most used for the bladder-dart and the bird-dart; it has at the upper narrow end a knob which fits into an indentation in a plate of bone fixed to the butt end of the dart. (Compare illustrations on pp. 40 and 42). The other form is used for harpoons and lances; it has a hole in the upper narrow end, into which fits a backward-slanting spur in the side of the harpoon or lance-shaft, and it has besides another hole further down and near the grip, into which fits another slanting spur. (Compare illustration, p. 43). Throwing-sticks of this sort are used in the North, for example in Sukkertoppen, for the bird-dart as well.

A third form of the throwing-stick is used in the most southern part of Greenland and on the east coast for the ernangnak or flange harpoon. This form has in its upper narrow end a small knob, as in the bird-dart throwing-stick, and this knob fits into an indentation in the butt end of the harpoon between the bone flanges; in the lower end of the shaft, on the other hand, near the grip, there are one or even two holes into which fit bone knobs in the side of the harpoon shaft, as above described.

When the harpoon or the dart is to be hurled, the throwing-stick, of whatever form it may be, is seized by the grip and held backward, together with the weapon, in a horizontal position. (See illustration, page 40); being then jerked forward with force, its lower end comes away from the dart or harpoon, while, with the upper end, still fitted to its knob or peg (see illustrations on this and the next page), the thrower hurls the weapon away to a considerable distance and with great accuracy. This is an extremely simple and effective invention.

Besides the weapons above mentioned, the Eskimo has behind him in his kaiak, when he goes out hunting, a knife with a handle about 4 feet long (1.20 metre) and a pointed blade measuring some 8 inches (20 centimetres). This is used for giving the seal or other game its finishing stroke. He has, moreover, a smaller knife lying before him in the kaiak; it is used, amongst other things, for piercing holes in the seal through which to pass the bone knobs of the towing-line, wherewith the seal is made fast to the kaiak and towed to land. To this end, too, he always carries with him one or more towing-bladders, which he inflates and fastens to the seal in order to keep it afloat. These bladders are made of the pouch of small whales (e.g. the grampus).

To complete this description, I should also mention the bone-knife which forms part of the kaiak-man's outfit, especially in winter, and which is principally used for scraping the ice off the kaiak.

From the accompanying drawing, the reader will be able to form an idea of how all these weapons are fitted to the kaiak when it is in full hunting trim: a is the kaiak-opening; b, the harpoon-bladder; c, the kaiak-stand with coiled harpoon-line (e); d, the harpoon hanging in its place; f, the lance; g, the kaiak-knife; h, the bladder-dart; i, the bird-dart; k, its throwing-stick.

But the most important thing of all yet remains, and that is a description of the kaiak itself.

It has an internal framework of wood. This, of which the reader can, I hope, form some conception from the accompanying drawing, was formerly always made of drift-wood, usually of the white wood, which is lightest. For the ribs, osiers were sometimes used, from willow bushes which are found growing far up the fiords. In later days they have got into the habit of buying European boards of spruce or Scotch fir in the west coast colonies, although drift-wood is still considered preferable, especially on account of its lightness.

This framework is covered externally with skins, as a rule with the skin of the saddleback seal (Phoca grœnlandica), or of the bladder-nose or hood seal (Cystophora cristata). The latter is not so durable or so water-tight as the former; but the skin of a young bladder-nose, in which the pores are not yet very large, is considered good enough. Those who can afford it use the skin of the bearded seal (Phoca barbata), which is reckoned the best and strongest; but, as it is also used for harpoon lines, it is, as a rule, only on the south and east coast that it is found in such quantities that it can be commonly used for covering the kaiak. The skin of the great ringed seal (Phoca fœtida) is also used, but not so frequently.

The preparation of the kaiak-skins will be described subsequently, in Chapter VIII. They are generally fitted at once to the kaiak in a raw state; but if they have been already dried they must be carefully softened for several days before they can be used. The point is to get them as moist and pliant as possible, so that they can be thoroughly well stretched, and remain as tense as a drum-head when they dry. The preparation of the skins, and the sewing and stretching them on the kaiak, belongs to the women's department; it is not very easy work, and woe to them if the skin sits badly or is too slack! They feel it a great disgrace.

All, or at any rate a great many, of the women of the village are generally present when a kaiak is being covered; it is a great entertainment to them, especially as, in reward for their assistance, they are often treated to coffee by the owner of the kaiak. The cost of the entertainment ranges, according to his wealth, from threepence or fourpence up to a shilling or more.

In the middle of the kaiak's deck there is a hole just large enough to enable a man to get his legs through it and to sit down; his thighs almost entirely fill the aperture. Thus it takes a good deal of practice before one can slip into or out of the kaiak with any sort of ease. The hole is surrounded by the kaiak-ring, which consists of a hoop of wood. It stands a little more than an inch (3 or 31⁄2 centimetres) above the kaiak's deck, and the waterproof jacket, as we shall presently see, is drawn over it. At the spot where the rower sits, pieces of old kaiak-skin are laid in the bottom over the ribs, with a piece of bearskin or other fur to make the seat softer.

As a rule, each hunter makes his kaiak for himself, and it is fitted to the man's size just like a garment. A kaiak for a Greenlander of average size measures, in the neighbourhood of Godthaab, about 6 yards (51⁄2 metres) in length. The greatest breadth of deck, in front of the kaiak-ring, is about 18 inches (45 centimetres), or a little more; but the boat narrows considerably towards the bottom. The breadth, of course, varies according to the width of the man's thighs, and is generally no greater than just to allow him to slip in. I should note, however, that the kaiaks in Godthaab fiords—as, for example, at Sardlok and Karnok—were longer and narrower than the kaiaks on the sea-coast, for example at Kangek, obviously for the reason that on the open coast they are exposed to heavier seas, and must therefore be stiffer and easier to handle. The shorter and broader kaiaks are better sea-boats, and ship less water.

(The dotted line presents the skin.)

The depth of the kaiak from deck to bottom is generally from 5 to 61⁄2 inches (12 to 15 centimetres), but in front of the kaiak-ring it is an inch or two more, in order to give room for the thighs, and to enable the rower to get more easily into his place. The bottom of the kaiak is pretty flat, sloping to a very obtuse angle (probably about 140°) in the middle. The kaiak narrows evenly in, both fore and aft, and comes to a point at both ends. It has no keel, but its underpart at both ends is generally provided with bone flanges, for the most part of whale-rib, designed to save the skin from being ripped up by drift-ice, or by stones when the kaiak is beached. Both points are commonly provided with knobs of bone, partly for ornament, partly for protection as well.

Across the deck, in front of the kaiak-ring, six thongs are usually fastened, and from three to five behind the rower. Under these thongs weapons and implements are inserted, so that they lie safe and handy for use. Pieces of bone are let into the thongs, partly to hold them together, partly to keep them a little bit up from the deck, so that weapons can the more easily and quickly be pushed under them, and partly also for the sake of ornament. To some of these thongs the booty is fastened. The heads of birds are stuck in under them; seals, whales, or halibut are attached by towing-lines to the thongs at the side of the kaiak; and smaller fish are not fastened at all, but either simply laid on the back part of the deck or pushed in under it.

A kaiak is so light that it can without difficulty be carried on the head, with all its appurtenances, over several miles of land.

It is propelled by a two-bladed paddle, which is held in the middle and dipped in the water on each side in turn, like the paddles we use in canoes. It has probably been developed from the Indians' one bladed paddles. Among the Eskimos on the southwest coast of Alaska the one-bladed paddle is universal; not until we come north of the Yukon River do we find two-bladed paddles, and even there the single blade is still the more common. Further north and eastward along the American coast both forms are found, until the two blades at last come into exclusive use eastward of the Mackenzie River.

The Aleutians seem, strangely enough, to be acquainted with only the two-bladed paddle,[5] and this is also the case, so far as I can gather, with the Asiatic Eskimos.[6]

In fair weather the kaiak-man uses the so-called half-jacket (akuilisak). This is made of water-tight skin with the hair removed, and is sewn with sinews. Round its lower margin runs a draw-string, or rather a draw-thong, by means of which the edge of the jacket can be made to fit so closely to the kaiak-ring that it can only be pressed and drawn down over it with some little trouble. This done, the half-jacket forms, as it were, a water-tight extension of the kaiak. The upper margin of the jacket comes close up to the armpits of the kaiak-man, and is supported by braces or straps, which pass over the shoulders and can be lengthened or shortened by means of handy runners or buckles of bone, so simple and yet so ingenious that we, with all our metal buckles and so forth, cannot equal them.

|

|

| HALF-JACKET. | WHOLE-JACKET. |

Loose sleeves of skin are drawn over the arms, and are lashed to the over-arm and to the wrist, thus preventing the arm from becoming wet. Watertight mittens of skin are drawn over the hands.

This half-jacket is enough to keep out the smaller waves which wash over the kaiak. In a heavier sea, on the other hand, the whole-jacket (tuilik) is used. This is made in the same way as the half-jacket, and, like it, fits close to the kaiak-ring, but is longer above, has sleeves attached to it, and a hood which comes right over the head. It is laced tight round the face and wrists, so that with it on the kaiak-man can go right through the breakers and can capsize and right himself again, without getting wet and without letting a drop of water into the kaiak.

It will readily be understood that it is not easy to sit in a vessel like the kaiak without capsizing, and that it needs a good deal of practice to master its peculiarities. I have seen a friend of mine in Norway, on making his first experiment in my kaiak, capsize four times in the space of two minutes; no sooner had we got him up on even keel and let him go, than he again stood on his head with the bottom of the kaiak in the air.

But when one has acquired by practice a mastery of the kaiak and of the two-bladed paddle, one can get through the water in all sorts of weather at an astonishing speed. The kaiak is beyond comparison the best boat for a single oarsman ever invented.

In order to become an accomplished kaiak-man, one ought to begin early. The Greenland boys often begin to practise in their father's kaiak at from six to eight years old, and when they are ten or twelve the provident Greenlander gives his sons kaiaks of their own. This was the rule, at any rate, in former times. Lars Dalager even says: 'When they are from eight to ten years old they take seriously to work in little kaiaks.'

From this age onwards, the young Greenlander remains a toiler of the sea. At first he generally confines himself to fishing, but before long he extends his operations to the more difficult seal-hunting.

You cannot rank as an expert kaiak-man until you have mastered the art of righting yourself after capsizing. To do this, you seize one end of the paddle in your hand, and with the other hand grasp the shaft as near the middle as possible; then you place it along the side of the kaiak with its free end pointing forward towards the bow; and thereupon, pushing the end of the paddle sharply out to the side,[7] and bending your body well forward towards the deck, you raise yourself by a strong circular sweep of the paddle. If you do not come right up, a second stroke may be necessary.

A thorough kaiak-man can also right himself without an oar by help of his throwing-stick, or even without it, by means of one arm. The height of accomplishment is reached when he does not even need to use the flat of his hand, but can clench it; and to show that he really does so, I have seen a man take a stone in his clenched hand before capsizing, and come up with it still in his grasp.

An Eskimo told me of another who was so extraordinarily skilful at righting himself that he could do it in every possible way: with or without an oar, with or without a throwing-stick, or with his clenched hand. The only thing he could not right himself with was—his tongue; and my informant protruded that member and made some horrible grimaces with it to illustrate what exertions it would cost to recover yourself with so inconvenient an implement.

In earlier times, on the west coast of Greenland, every at all capable kaiak-man was able to right himself; but in these later days, since the introduction of European civilisation, and the consequent degeneracy of the race, this art has declined, along with everything else. It is still quite common, however, in many places. For instance, I can assert of my own knowledge that at Kangek, near Godthaab, almost all the hunters possessed it. On the east coast, according to Captain Holm, it seems to be usual, yet not so much so as it was in former times upon the west coast. Nor is this to be wondered at, as it is far more necessary on the west coast, where there is little drift ice and heavy seas are common.

A kaiak-man who has entirely mastered the art of righting himself can defy almost any weather. If he is capsized, he is on even keel again in a moment, and can play like a sea-bird with the waves, and cut right through them. If the sea is very heavy, he lays the broadside of his kaiak to it, holds the paddle flat out on the windward side, pressing it against the deck, bends forward, and lets the wave roll over him; or else he throws himself on his side towards it, resting on his flat paddle, and rights himself again when it has passed. The prettiest feat of seamanship I have ever heard of is that to which some fishers, I am told, have recourse among overwhelming rollers. As the sea curls down over them they voluntarily capsize, receive it on the bottom of the kaiak, and when it has passed right themselves again. I think it would be difficult to name a more intrepid method of dealing with a heavy sea.

If you cannot right yourself, and if there is no help at hand, you are lost beyond all hope as soon as you capsize. This may happen easily enough—a wave can do it, or even the fouling of the harpoon-line when a seal is struck. Just as often, too, it happens through an unguarded movement in calm weather, or at moments when there seems to be no danger.

Many Eskimos find their death every year in this manner. For example, I may state that in Danish South Greenland in 1888, out of 162 deaths (of which 90 were of males), 24, or about 15 per cent. (that is to say, more than a fourth part of the male mortality), were caused by drowning in kaiaks.

In 1889, in South Greenland, out of 272 deaths (of which 152 were of males), 24, or about 9 per cent., were due to the same cause. This in a population of 5,614, of which 2,591 were males.

- ↑ The Indians of the North-West and the Tchuktchi—and even, if I am not mistaken, the Koriaks and the Kamtchatkans—use the same harpoon, with a line and large bladder, in hunting sea animals, throwing the harpoon from the bow of their large open canoes or skin-boats. It seems probable, however, that they have learned the use of these instruments from the Eskimos.

- ↑ In North Greenland there is yet a third and larger form of the harpoon, which is used in walrus hunting, and is hurled without a throwing-stick; it has instead two bone knobs, one for the thumb and one for the forefinger.

- ↑ As to the different forms of the throwing-stick among the Eskimos, see Mason's paper upon them in the Annual Report, &c. of the Smithsonian Institution for 1884, Part II. p. 279.

- ↑ In some places—for example, in the most southern part of Greenland and on the East Coast—there is only a hollow for the thumb, while the other side is smooth or edged with a piece of bone in which are notches to prevent the hand from slipping.

- ↑ On this point, see even such early authors as Cook and King, A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean, &c., 3rd ed., ii. p. 513, London, 1785.

- ↑ It is remarkable that the inhabitants of St. Lawrence Island do not seem to use the kaiak at all. They have large open skin-boats (baidars) of the same build as those of the Tchucktchi. (Compare Nordenskiöld, The Voyage of the Vega, ii. p. 254, London, 1881.)

- ↑ While the paddle is being pushed out sideways, until it comes at right angles to the kaiak, it is held slightly aslant, so that the blade, in moving, forces the water under it, and acquires an upward leverage.