Face to Face with the Mexicans/Chapter 1

MEXICAN PLAZA, FOUNTAIN, AND CATHEDRAL.

FACE TO FACE WITH THE MEXICANS.

CHAPTER I.

A NEW HOME AND NEW FRIENDS.

These piercing cries rang out again and again on the still morning air in the long ago from the lips of a terrified Tlaxcalan boy away up in the Sierra Madre Mountains.

But what do they mean?

As is well known, Mexico is a land of song, romance, and tradition, and these are inseparably intertwined in the lives of the people. Every noted spot has its legend, which descends not only to posterity but also to strangers. As the tradition about the founding of Saltillo lends something of interest to a sojourn of several months in that city, I tell it as it was told to me; in doing so reserving the right to say that, like most traditions, it has a decidedly made-to-order air.

The little Indian boy before mentioned had an aged, infirm, and blind old uncle. Now, it was a strange fancy of this blind man to take a stroll very early every morning, and it was the duty of this little nephew to hold him by the hand as a guide to his steps, as well as to amuse and entertain him on the way.

The spring known in Saltillo as El ojo de agua (the eye of water) breaks boldly forth from the craggy rocks, and in its fall transforms itself into a pool of considerable depth. The water is as cold as ice, and shimmers and glistens in the white sunshine as it reflects on its crystal surface the towering mountains and the deep azure of a faultless sky.

This spring supplies the entire city with water, which is conveyed through antiquated earthen pipes to the fountains, and thence borne by carriers into the houses.

But to the tradition: This inconsiderate old uncle was being led by his nephew, who was endowed with the very same tastes and instincts as all other boys, regardless of caste or complexion, the world over. As they approached the ojo de agua, the whirring sound of a thousand birds in flight over their heads caused the boy to drop his uncle's hand and look upward, with head thrown back, straight hair standing at right angles, and great, wild, black eyes, gazing at the myriad of birds that seemed to mottle the whole sky.

The uncle having no support, began to totter and hold out his arms, calling loudly, but to no purpose, for his forgetful guide. Inch by inch the old man felt his way over the rough stones; a step more, and there was a plunge, a scream, and the unfortunate uncle was floundering in the "eye of water." The young truant was recalled to himself, but, being paralyzed with fright, could only scream and wring his hands wildly, exclaiming:

"Saltillo! Saltillo!" (Get out, uncle!)—an injunction as heartless as it was impossible to obey.

At this critical moment, some passing arriéros (mule-drivers) compassionately rescued the drowning man, and so happily ends the tradition.

Posterity, studying out of cold, unsympathetic lexicons all kinds of puzzling derivations, finds, according to some, that the verb salir signifies "to go out;" sal, the first syllable, means "get out;" and tio (uncle) has, as perhaps in this case, been mispelled or corrupted into tillo, as Saltillo (pronounced Sal-tee'-yo), the liquid ll being more euphonious in the Mexican tongue.

Others yet believe that Saltillo comes from the language of the Chichimecas, and signifies "High land of many waters." In almost any direction may be seen innumerable sparkling cascades of limpid water bursting from the apex of the mountains, descending in a crystal sheet, and reflecting the prismatic glories of the rainbow as they go murmuring along to the valleys below. This may give credence to this version. Saltillo is the capital of the State of Coahuila.

The name Coahuila, according to some historians, means "Happy Land," while others claim its signification to be "Vibora que vuela" (flying snake). It is possible that this latter is the real derivation, as snake in the Indian is Coatl, and huila means to fly. This, taken together, may have some reference to the great temple of Huitchiolopochtly, the Aztec war god, which was surrounded by a square wall called coatlpantli (snake wall), carved within and without with myriads of these creatures. In the minds of those who had the naming of the States there must have been an idea that the bleak and barren aspect of Coahuila was sufficient to cause the exodus of even these not over-fastidious reptiles.

In view of these forbidding physical features, the term "Happy Land" must have been given in a spirit of satire; or perhaps some consumptive writer of poetic verse, enchanted by the fine dry climate, pure atmosphere, and blue skies, bestowed the title in gratitude for their salubrious effects.

Saltillo was once also the capital of Texas when that great State formed an unwilling member of the Mexican federation. It has a population of about twenty thousand, and is situated on the Buena Vista table-land in the Sierra Madre Mountains, at an elevation of about five thousand five hundred feet above sea-level.

It was founded on the 25th of July, 1575, by one Francisco Urdiñola, who brought with him sixty Tlaxcalan families who were bitter foes of the Aztecs and firm allies of the conquerors.

The city is the seat of important manufactures, both woolen and cotton. Here are made rebozos (a long narrow shawl worn by women over their heads), and also those gorgeous and durable serapes (blankets), of finest wool and most brilliant colors, which have gained so wide a celebrity that the term "Mexican blanket" is a synonym for a genuine and almost everlasting fabric. It has the usual places for recreation, a bull-ring, plaza, and alameda; a cathedral worthy of inspection, also numerous churches, with a full quota of schools and colleges.

We were a party of Americans on business, health, and pleasure bent. Our company consisted of Mr. and Mrs. R——, the former a retired banker from a large western city; Mr. and Mrs. A——, Mrs.

CALLE REAL, SALTILLO, SHOWING PLAZA ON THE RIGHT, A CORNER OF THE CATHEDRAL GARDEN ON THE LEFT, EXTENDING UP THE MOUNTAIN, WITH VIEW

OF AMERICAN FORT IN EXTREME LEFT-HAND CORNER.

S—— and daughter, my husband and self. As the hotel accommodations were meager and uncomfortable, and it not being the custom of the country for families to live in hotels, we concluded to go to housekeeping, as our stay was indefinite, and might extend through a few weeks or months.

We found this picturesque old city teeming with interest; many quaint old adobe bridges span the arroyos (dry streams), and the drives through the orchards in the Indian pueblos adjoining are full of exhuberant life and color. The noblest view is from the brow of the San Lorenzo, where are situated the fine medicinal springs and baths which tourists as well as natives enjoy. The drives in whatever direction are full of thrilling historic associations, the city having been the coveted ground of the contesting forces in untold battles and desperate encounters.

But no street or highway interested me so much as Calle Real, one of the principal and most delightful thoroughfares of the city. By a circuitous route and steep ascent it led to the American fort, and, circling to the right over the smooth table-lands, on to La Angostura (the Narrows), where lies the famous battle-field of Buena Vista.

Since the founding of the city, Calle Real has figured conspicuously in its history. The patriot Hidalgo and his chosen brave followers must doubtless have passed down this street to meet their fate—betrayed by friends.

The history of this grand captain's career was fresh in my mind, and, as I looked upon this long, narrow, and winding street, I pictured the fearless leader of the great cause of the Mexican people, with head erect and eye as bright as, when a victor, he heard the wild plaudits from the thousand dark brothers of his race who had flocked to his standard.

Then the scene would change, and the forms of my own martial countrymen, who had so often passed up and down this street, nearly two score years ago, would take the place of the dauntless Hidalgo. I lost sight of the present, and saw American soldiers, with stars and stripes floating proudly, move rapidly in solid columns of infantry, and heard the tread of the bronzed cavalrymen, and the rattle of sabers and the clear-ringing words of command in my own language. I saw the angry gleam of dark eyes and heard mutterings in the strange tongue as the Americans marched up the steep hill to take possession of the fort that commanded the city.

Another change: the shade of Hidalgo has vanished; the stars and stripes no longer float under the unclouded sky. In imagination I see the flag of the French Empire and the eagles of Austria streaming over the city, and the gorgeous uniforms of the soldiery of two mighty empires mingling with the rude, dark forms that look on them with wondering eyes of mute protest and reluctant admiration. Wild carousal is heard on every side, and wine flows like water. The harsh accents of the Austrian and the volatile utterances of the Frenchman fill the air.

The panorama moves on. Gone are the foreigners. Their chief lies dead in the stately burial place of the Habsburgs. Miramon and Mejia rest in San Fernando, and the banner of the Republic, with its emblematic red, green, and white bars and fierce eagle, waves proudly over the people freed from a foreign foe and hated alien rule.

War and revolution have yielded in turn to the softening influences of well-earned peace and tranquillity. The passions of those perilous times are long since dead; our quondam enemy is now our friend, and an American woman is at liberty to peacefully erect her household gods among them.

Both courage and resolution were necessary in transplanting ourselves to this terra incognita; but the climate, the hospitality of the people, the beautiful scenery, the novelty of the surroundings, which every day afforded delight, would of themselves reconcile one to exchanging the old, the tried, and the true for the experiences of an unknown world.

The house selected for our Bohemian abode, we were assured, was almost one hundred years old, and had an air of solemn dignity and grandeur about its waning splendor. It was of startling dimensions, capable of quartering a regiment of soldiers with all their equipments. It was one story in height, with a handsome orchard and garden in the rear, extensive corrals for horses, the whole extending from street to street through a large square of ground.

The distinguishing features of Mexican and Spanish architecture were evident throughout the patio (court-yard), with fountain in the center, flat roof, barred windows, and parapet walls. These latter rise often to the height of six feet above the main structure, and, in times of war and revolution, have proved admirable defenses to the besieged. Intrenching themselves behind these walls, passage-ways are made from one house to the other, until the entire block of buildings is one connected fortification. The strife may continue for weeks uninterruptedly, the fusillade not ceasing long enough to remove the dead from the streets.

The size and unwieldiness of the front doors were amazing—noble defenses in time of revolution, it is true, but when with my whole strength I could not move one on its antiquated, squeaking hinges, almost a half yard in length, the question of how to pass from house to street became a serious one. The happy discovery was made at last that, instead of two, there were four doors all in one, the two smaller ones within the greater serving for our usual ingress and egress. The huge double doors, spacious enough to admit a locomotive with its train of cars, were never opened except on state occasions or for the admittance of a carriage, buggy, or something out of the ordinary, such as a dozen or so wood-laden donkeys. Not only funerals and bridal parties, but every imaginable household necessity for pleasure or convenience, must pass through the front doors.

In the zaguan (front hall), high up in the cedar beams, darkened by age to the color of mahogany, was this inscription or dedication in large, clear letters: "Ave Maria Santissima." In other houses these dedications varied according to taste. One read "Siempre viva en esta casa Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe" (May the Virgin Guadalupe always watch over this house). Still another inscription in the house of a friend read: "Aqui viva con V. Jose y Maria" "May Joseph and Mary dwell with you here."

We were astounded at the size and length of the keys, and the number of them; they were about ten inches long, and a blow from one would have sufficed to fell a man. As there were, perhaps, thirty of them, my key-basket, so far from being the dainty trifle an American woman dangles from one finger in her daily rounds, would have been a load for a burro, as they call their little donkeys. The enormous double doors connecting the rooms were as massive as if each room were intended for a separate fortification. The opening and

closing of these heavy doors as they scraped across the floors gave forth a dull, grating sound which added to the loneliness of our castle.

Our venerable mansion was constructed of adobe, the sundried brick peculiar to the country, and of which almost the entire city is built. The walls were from two to four feet in thickness, and the ceilings thirty feet in height. Surrounding the beautiful court-yard were many large and handsome rooms, frescoed in brilliant style, each different from the other. Besides these there were many smaller apartments, lofts, nooks, and crannies, more than I at first thought I should ever have the courage to explore.

The drawing-room was the first thing to attract my attention, as it was about a hundred feet long and fifty wide. Its dado was highly embellished by a skillful blending of roses and buds in delicate shades, while the frieze was the chaste production of a native artist. The ceiling, as before mentioned, was thirty feet in height, and another source of surprise to me was the discovery that the foundation of all this elaborate workmanship was of the frailest material. These wonderful artisans, in making ceilings that are apparently faultless, use only cheese-cloth. After stretching it as tightly as possible, and adding a coat of heavy sizing, the beautiful and gorgeous frescoes are laid on, and the eye of an expert cannot detect the difference between a cloth ceiling and the more substantial plaster with which we are familiar in the United States.

The floor of this room presented another subject of inquiry as to its materials and the method employed in making it so hard, smooth, and red. Mortar, much the same as is used for plastering, but of a consistency which hardens rapidly, is the basis of operations. On this a coating of fine gravel, very little coarser than sand, is applied. Then comes the final red polish which completes a floor of unusual coolness and comfort, and admirably adapted to the country. The material used to give the red finish is tipichil, an Indian word, in some places known as almagra, an abundant earthy deposit to be found principally in the arroyos. For ages this substance has been an important article for ornamentation, even the wild tribes of Indians using it to paint their faces and bodies. When the floor is hardened, a force of men is employed, who, by rubbing it with stones, produce a beautiful glazed polish. If time were of any value, these floors would cost fabulous sums, as it takes weeks to complete one of them. It required months almost for me to comprehend the manner of cleaning them. The floors of the other rooms were of imported brick and tiles, the former not less than a foot square and perhaps half as thick, while the latter were octagonal and of fine finish, though, like the mansion itself, they bore the evidences of age and decay.

We enjoyed the unusual luxury of glass windows, and it was enough to puff us up with inordinate pride to look out and see our neighbors' houses provided with only plain, heavy wooden shutters. When it rained or was cold, however, our ill-fitting windows proved an inadequate protection, and it became necessary to close the ponderous wooden shutters, thus leaving the rooms in total darkness.

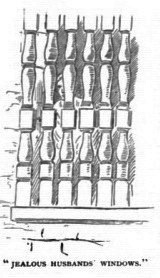

Our windows were also furnished on the outside with iron rods, similar to those used for jails in the United States, and quite as effective, while those of many of our neighbors had only heavy wooden bars, so close together as scarcely to permit the hand to pass between them. These, I was told by a Mexican lady, were called "jealous husbands' windows."

In the middle of many of the shutters of some of these houses were tiny doors, whose presence, when closed, would never be suspected. They were just large enough for a face to peer through, and when passing along the street on cold or windy days, hundreds of soft, languishing, dreamy eyes might be seen gazing out of these little windows.

In Mexican architecture the window is second in importance only to the roof itself. For, the next thing to being protected from the rain, is the necessity for the family to be able to see into the street. The walls are of such thickness that one window will easily accommodate two of their quaint little home manufactured chairs, and as there is no front stoop, each afternoon finds the señoritas seated in these chairs, taking in the full enjoyment of the usual street scenes. The illustration on page 43 shows a señorita in the window, while on the other side a view is had of the little window that is opened on a cold or rainy day.

The roof being flat, was constructed in a unique manner, having first heavy wooden beams laid across the top of each room, and then planks coated with pitch placed on these, after which twelve inches of mother earth were added; then a coating of gravel, and lastly one of cement, the whole making a roof impervious to rain or heat, and proving the admirable adaptability of Mexican architecture to the climate and the people.

The houses in general are provided with roofs of adobe, and some of the plainer ones in which I became a visitor, when the rainy season was at its height, gave me an amusing insight into the freaks and tricks of the "doby." as they are familiarly termed. When there were no frescoes on the cheese-cloth canvas, it would be taken down periodically, washed and then replaced as smoothly as a plaster ceiling. But woe betide the "doby" roof, when the rainy season makes its advent. The treacherous mud covering succumbs to the pressure of the driving water, and often the entire room or house is submerged in the twinkling of an eye. Besides the main leaks, numerous little bubble-like projections, like pockets, each filled with water, sagged down the canvas in various places. To my great amusement I found that my ingenious native friends had always on hand the essentials for stopping the leak, such as an old broom handle or strip of wood, which by the aid of a bent pin and a string, manipulated by dexterous fingers, soon repaired all damages.

First, all the little sacks of water are conducted by means of the broom handle into the larger one, where the bent pin has been previously attached to the canvas and also to one end of the string. To the other end the strip of wood is fastened, and under this a bucket placed. Twenty minutes from the time of the first onslaught of the torrent through the roof all is serene and calm as a May morning. Orders were given at once to the mozo to sow the roof with grass-

WATER SPOUTS.

seed, so as to prevent another catastrophe. No greater protection is found for an ordinary earthen roof than that afforded by a solid greensward. The roots form a compact net-work, so that it must be an unusually heavy storm that can penetrate it.

The method of conducting the water from the roof is in keeping with everything else. Great heavy gargoyles or stone spouts, weather-beaten and moss-covered, tipped with tin, full ten feet in length, six in a line on either side of the court, answered the purpose in our mansion. During a heavy rain-storm it was interesting to watch the steady streams of water foaming and surging into the court. I saw a dog

VIEW IN A COURTYARD.

knocked senseless to the ground by one of these streams, and it was several minutes before he recovered his breathing and yelping faculties.

The ends of these spouts, in many instances artistically ornamented, protrude over the street. In more modern houses conduits, a few inches wide, are cut into the sides of the wall and cemented, taking the place of the stone spouts. They are quite as effective, but the quaintness and antique appearance of the houses is greatly diminished by them.

In the carriage-house there still remained a silent old relic of Mexican grandeur and aristocratic distinction, with wheels like an American road-wagon and hubs like a water-bucket. In the garden were fruit-trees and the family pila (bath). The latter was built of adobe, three feet high and twelve feet square, without cover, the water being supplied by means of earthen pipes from the mountain springs. A fountain and exquisite flowers adorned the patio, a climbing rose of unusual luxuriance at once attracting special notice. It was evergreen, and of extraordinary size, extending in graceful festoons fully one hundred feet on either side. We were told that at the time of the occupation of Saltillo by Taylor's army this same vine was an attractive feature of the court.

Imagine the dismay and apprehension of several American women at thus finding themselves surrounded by so many evidences of ancient refinement and culture, and yet by none of the modern necessaries of housekeeping. In this old city of twenty thousand inhabitants there was not a store where such indispensables as bedsteads or furniture of any kind, pillows or mattresses, could be purchased; while coffee or spice mills, cook-stoves or wash-tubs, were absolutely out of the question. How we managed may prove interesting to those who contemplate taking up their residence in Mexico, and will be related in the succeeding chapters. It was not by any means a question of money or price that prevented one from being comfortable at the outset.

We ladies were constantly portraying to each other, in a humorous way, how frightened we should be if circumstances should ever require any one of us to remain alone in this old castle over night; of how the ghosts and hobgoblins that were perhaps concealed in some unexplored crannies might come forth in all their blood-curdling hideousness. These idle fancies and banterings of the hour were vividly recalled one night, when I unfortunately found myself the only one to entertain the phantom visitors.

Every other member of the household had gone for a day's jaunt into the country, and was detained from home over night by a terrific rain and thunder storm. The servants, supposing they would return, went to their homes, as is customary, which I did not discover until after they had left.

In the dead hours of the night I was aroused from deepest sleep by a terrific noise. Quaking with fear in the dim light, and gripping the pistol which was on a chair at the head of my bed, I proceeded, like Rosalind, with a "swashing and martial outside," to reconnoiter. A brief investigation revealed the fact that the fancied ghost or hobgoblin was nothing more alarming than a "harmless necessary cat," which had crept in surreptitiously through the bars, on feline mischief bent. By a misstep of her catship there was a general crash of crockery, and the sudden clatter, breaking with startling effect on the stillness of the night, made me imagine that the hobgoblins had really trooped forth from their hiding-places.

I had flattered myself that the diligent study I had given the grammar, previous to my going to Mexico, would prove an " Open, Sesame!" to the language, but I soon found myself sadly mistaken when I heard it spoken idiomatically and with the rapid utterance of the natives. But by eagerly seizing every opportunity, however humble, of airing my incipient knowledge, and by aid of grammar and dictionary, my inseparable companions, I found myself in a few weeks equal to the exigencies of the case, and rattled off my newly acquired accomplishment with a reckless disregard of consequences.

Speculation and curiosity were ever on the alert to make discoveries in this old house, and at every turn a thousand echoes seemed answering my timorous step.

Generations had here lived their lives of sorrow and joy, and the lightest vibration seemed the ghost of some long-past sigh or laugh, to which these walls had resounded ; and to me these vast old rooms were peopled again by my own vivid imaginings. To walk twice or thrice around the court-yard and through this interminable array of rooms, seemed as fatiguing as half a day's tramp.

In one of these perambulations I opened the door of a room into which I had never ventured before. An ancient-looking cupboard stood in one corner, filled with odd remnants of dainty china, vases, bottles, plates, glass, a dilapidated but highly decorated old soup tureen, and some pieces of broken crockery almost half an inch in thickness. Many faded letters were thrown loosely about on shelves and in crevices. A descendant of Mother Eve could do no less than look at the dates. Some were a hundred years old, written in Spain, and the chirography was exceedingly beautiful. One was written in the city of Mexico, by a husband to his wife. He wrote most tenderly to the pretty, young esposa, begging her to be patient until his return, which was to be in the near future.

Hanging upon the wall near the door was a well-executed oil portrait, representing a lovely Spanish face. The graceful pose of the figure attracted my attention, and the luminous, speaking eyes held me spellbound — the same eyes which have so long made Spanish and Mexican women famous in song and story. The patrician nose, the classic brow, the shapely, rosy-lipped mouth, and the perfect hand and arm, completed a picture of unusual beauty. A richly gemmed crown rested upon the dark hair, and in the lower corner of the picture, inside the massive, gilded frame, were the words : "Ana su digna esposa" — "Hannah, your worthy wife."

Carefully removing all dust and cobwebs, I carried my prize to the drawing-room, and hung it over the mantelpiece. I am sure I never passed it without glancing at that perfect face, so sweet and womanly in its expression, and experiencing feelings of mingled reverence and pleasure.

Much diligent inquiry on my part elicited the information that the portrait was of Doña Ana, wife of the Emperor Augustin de Iturbide, the first and only crowned head to occupy a throne in North America since its settlement by Europeans.

The first Sunday morning after taking possession of our house, I was sitting in the sunshiny court alone, every one, even the mozo, being absent. The bells from perhaps half a dozen churches answered each other across the bright air, reminding me with some painfulness of the church bells in my American home, the thought of which had filled my mind with longings all the morning, as I saw the gayly dressed populace hurrying past on their way to mass. Suddenly there was a gentle tap on the ponderous outer door. Responding, I found myself confronted by a tall youth of perhaps sixteen, fair, rosy cheeked, black haired, dark eyed, and beautiful. He lifted his hat politely and said in good English, "Good-morning, Madame!"

The sound of my dear native tongue in a land of strangers and from the lips of one of them brought my heart into my mouth with delight and surprise. My visitor introduced himself as Jesus, taking care to spell his name plainly for me, and I fear my face betrayed my horror at the sight of an ordinary mortal endowed with that holy name. He informed me with considerable hesitation that he was a student in the college, and wished to call frequently to have an opportunity of conversing in English.

Having obtained permission to call whenever it pleased him, he asked if he might bring a friend. Accordingly, Antero P—— was introduced —another promising youth, equally determined to improve his English. They soon brought others, and among my most pleasing recollections are the occasions when the college boys— sometimes a dozen — gathered about me on Sunday mornings, with bright, dark faces, flashing eyes, and determined expression, as they wrestled with the difficulties of our language. Their great deference and thoughtfulness for me added to the pleasure I derived from their visits, — for the advantage was mutual. I learned the Spanish while they conquered the English.

I could not but pity the other members of our party who so languished with home sickness that they quite failed to reap the pleasure I did from this study of the natives. Every day I found some new object of interest, and after the house had been explored I spent hours gazing from the windows upon some of the strangest scenes I had ever beheld. Some were extremely pathetic and others mirth-provoking.

The young children of the lower classes, especially the girls from five to ten years, were objects of peculiar interest to me. Dozens of these were to be seen in the early morning hours going upon some family errand apparently, judging from the haste and the pottery vessels they carried. Their tangled hair, peeping out from under the rebozo, their unwashed faces and jetty eyes, their long dresses sweeping the ground — and looking like the ground itself — their little naked, pigeon-toed feet going at an even but rapid jog-trot, all formed a laughable and ridiculous picture.

Often their hands were thrust through the bars, begging money in the name of some saint for a sick person.

"Tlaco, Señorita, pa comprar la medecina para un infermo" ("A cent and a quarter, lady, to buy medicine for a sick person"). If I asked what was the matter, the reply, '' Tiene mal de estomago" ("Sick at the stomach"), came with such unfailing regularity, I was forced to the conclusion that "mal de estomago" must be an epidemic among them.

The school children came in for a profitable share of my most agreeable observations, as they presented themselves before me in all their freshness and originality.

It is not the custom for the daughters of the higher classes to appear on the street unattended. I rightly concluded, therefore, that these happy little friends of mine, who created such a fund of amusement for me, were the public-school children who belonged to the lower classes.

They passed in the mornings about eight o'clock, and returned at five in the evening. The girls wore rebozos differing from their mothers' only in size; and a surprising unanimity of style seemed to prevail.

Their hair was drawn tightly back, plaited behind, the ends doubled under, and almost universally tied with a piece of red tape. Their white hose, a world too short, had an antique look to eyes accustomed so long to the brilliantly arrayed legs of the children of the United States. Evidently extra full lengths had not reached that country, as the above-mentioned hose terminated below the knee, where they were secured (when secured at all) with a rag, string, or a piece of red tape of the same kind that adorned their braided locks. Those who wore shoes had them laced up the front, sharp pointed at the toes, and frequently of gay-colored material. As their dresses sometimes lacked several inches of reaching the knees, the intervening space of brown skin exposed to view was sometimes quite startling, especially so, if—as was often the case—their pantalets were omitted. Frequently, when these were worn, they were very narrow and reached the ankle, the dress retaining its place far above the knee. A row of big brass safety-pins down the front of their dresses performed the office of buttons.

The boys were simply miniature copies of their fathers, wearing sashes, snug little jackets, blouses, and in some cases even the sandal.

A GROUP OF MY LITTLE FRIENDS.

The advent of one of these light-hearted groups was always a happy diversion to me. Often they came laughing and chattering in a gentle monotone down the street, throwing paper balls at one another, playing "tag"—it has a finer and more sonorous name in their majestic tongue, for it rolled off euphoniously into "ahora tu me coges" ("now you've caught me")—performing many other pretty, childish antics just after some peculiarly heart-rending spectacle of poverty and suffering suffering had wrung my heart. They soon learned to divine my sympathetic interest in them, and occasionally some of them would stop before my window, and exchange with me amusing remarks. They were very bright, and laughed incredulously, exchanging winks and nods with each other, when I tried to make them believe that I was a Mexican. I asked if they could not see from my dark hair and eyes that I was one ; but they refused to be convinced, saying: "You may look like a Mexican, but you can't talk like one." In the course of time, all shyness vanished, and often, when in other parts of the house, the young voices gleefully calling "Señorita! Señorita!" would bring me to the drawing-room, and there would be my barred windows, full of little dark mischievous faces, their brown hands stretched out to me through the iron bars, through which their dancing eyes peeped. When my housekeeping was in better running order — comparatively speaking, of course — I sometimes gave them trifling dainties. Cakes they accepted gladly, but when in my patriotic zeal I tried to familiarize them with that bulwark of our Southern civilization — the soda biscuit — they rejected it uncompromisingly, spitting and sputtering after a taste of it, and saying: "No nos gusta" ("We don't like it"), "Good for Americans — no good for Mexicans."

A pretty child in a nurse's arms stopped before the window, and laid her tiny brown hand on me caressingly. Nurse told her to sing a pretty song for the señora, when she began :

No me mates! no me mates! no me mates!

Con pistola ni puñal;

Matame con un besito

De tus labios de coral.

Don't kill me! don't kill me! don't kill me!

With a pistol nor a dagger;

But kill me with a little kiss

Of your pretty coral lips.

I asked her to come again, and as they moved along the pretty creature waved her hand at me, saying: “Mañana! en la mañanita" ("Tomorrow morning very early "), which aroused my fears, justly enough, for I never saw her again, it being their universal custom to postpone everything for the morrow — a time which I felt would never come.

The mansion and its associations were so well known that every servant whom we employed could contribute some item of interest concerning its history. An old citizen related to me that at the time of Gen. Taylor's entrance into the city there were in it nine most beautiful and interesting señoritas, daughters of the original founder, Don A——. Naturally, every little detail and event concerning them was eagerly absorbed, and nothing gave me more thorough gratification than the discovery that my very first and best friends made after arriving were the descendants of one of these nine señoritas. Don Benito G——, an accomplished gentleman of Castilian descent, who has occupied the highest positions in the state, wooed and won his lovely bride when she was in her early teens, and for many years they remained under the paternal roof. Here their three beautiful children first saw the light, and their infantile days were spent in these grand old rooms, amid the flowers of the court and surrounded by an atmosphere of beauty and refinement.

At the time of our acquaintance these favored children of a distinguished family were in the bloom of early manhood and womanhood, José Maria, the eldest, aged twenty-six; Benito, twenty-two ; and Liberata, a lovely, dark-eyed girl of sixteen. She was a charming representative of her Andalusian ancestors; the graces of her person added to the beauty of her disposition. In imagination her exquisite flower- sweet face rises before me, her soft luminous eyes, shaded by lashes of wondrous length and beauty, sweeping a cheek that glowed like a luscious peach.

These friends began at once, without ceremony or ostentation, to show me the gentlest attentions, and from the unlimited treasure-house of their warm Mexican hearts they bestowed upon me a generous devotion that brightened my life and made me love and respect their land and their people for their sakes. In every circumstance they proved to be animated by the noblest impulses of our common nature, and one of the happiest discoveries I made during those days of a bewildering bewildering struggle with a new civilization, was that, despite the representation of many of my own countrymen, fidelity, tenderness, and untiring devotion were as truly Mexican characteristics as American. It is doubtful in my mind if the people of any country lavish upon strangers the same warmth of manner or exhibit the same readiness to serve them, as do our near-at-hand, far-away neighbors, the Mexicans.

At daylight one morning, soon after we were installed in the house of his ancestors, Don Benito, Jr., accompanied by several young friends, favored us with a delightful serenade, in which the beautiful Spanish songs were rendered with charming effect. He was an excellent sportsman, and always remembered us after his shooting excursions, while I received daily reminders of affectionate regard from Liberata, the gentle sister.

Don José Maria was a young man of varied accomplishments and acquirements, among which the knowledge of English was duly appreciated in our growing friendship. He had liberal and progressive ideas; was well versed in American literature, was a regular subscriber to the Popular Science Monthly, North American Review, Scriber´s, Harper's Magazine and Bazar, besides others of our best periodicals — and took a lively interest in our politics.

To all these magazines we had free access through his kindness, and welcome as waters in a thirsty land were these delightful home journals, where mails were had but once or twice a week in this literary Sahara.

After the death of his mother, when Liberata was only an infant desiring to relieve his grief-stricken father, this admirable elder brother took almost entire charge of the little creature, filling the place of mother, sister, and brother. It was to me an exquisitely pathetic story, this recital of the young brother's effort to train and care for the motherless baby girl, even superintending the buying and making of her wardrobe, which must have been the most bewildering feature of his bewildering undertaking.

Among other things he was anxious to have her become familiar with American methods of house keeping and cookery. I could but laugh, though a tear quickly followed, when she described how her brother translated the cooking receipts in Harper's Bazar, and then requested her to have American dishes concocted from them; what moments of despair she had over the unfamiliar compounds, and what horrible "messes" sometimes resulted from the imperfectly understood translations.

This devotion of brother to sister often recalled a similar experience in my own life. The ideal José Maria was my brother William, who had made a like idol of me. His was then a newly made grave, and I had only time to place a flower upon it before beginning the journey to old Mexico. While I had stepped across the boundary line of ages and was endeavoring to decipher the hieroglyphics of an Aztec civilization, which were stamped upon every form and feature that I saw, here I stood face to face with a repetition of my own life. It was but following the promptings of a woman's heart to believe in these kind strangers and to cherish their friendship.

In due time I had gathered about me many kind and congenial friends, who vied with each other in contributing to my happiness. One of these, Doña Pomposita R——, without knowing my language, began to instruct me in her own. Winks, blinks, and shrugs did the most of it: but come what would, she never gave up until everything was clear. We sat in the patio on the afternoon of her first visit, and among other things was her determination that we should converse about Don Quixote, she being familiar with his story in the original and I in my own tongue. Many of the humorous adventures of the Don were called up by her in the most amusing manner. In rapid succession she mentioned the men with their "pack-staves," the "wine-bags," and was finally overcome with laughter as she said that our grand old house reminded her of the isle of Barataria, where Sancho Panza was governor.

She then sang in a low, sweet tone many operatic airs, among them, "Then You'll Remember Me," and others equally familiar, possessing an added charm in the sweet Spanish. Near night-fall she arose to go home, saying Pancho — meaning her husband — would soon be there, and she wished him never to enter their home and find her absent. Placing her arm affectionately about my waist, in her sweet Spanish she said to me: "In my country it is very sad for you, and you are far from your home and people, but do not forget I am your friend and sister; what I can do for you shall be done as for a sister." Her husband, Don Pancho, shared fully in her professions of friendship, and on one occasion, when a hundred miles away from the city, sent us a regalo (gift) of a donkey-load of grapes.

In striking personal contrast were my two most intimate friends among Mexican women. Pomposita, like Liberata, had the petite figure, the dainty feet and hands peculiar to the women of that country; but unlike her, she possessed the high cheek-bones, the straight black hair, the brown skin indicating her Indian origin, of which she was justly proud.

But there was no contrast in the exhibition of their devoted kindness and friendship. Both were equally ready to assist me in adapting myself to the strange order of things and to aid in my initiation into the mysteries of their peculiar household economies. In case of sickness it seemed worth while to suffer to be the object of such exquisite tenderness, and experience the unspeakable sweetness of their sisterly ministrations.

But the time came when an overwhelming affliction fell upon me, when the night with its countless stars and crescent moon told of no serene sphere where tears and grief are unknown. The shadows passed over my soul without a gleam to enlighten the gloom of the grave.

The oft-read promise to grief-stricken humanity, "Thy brother shall rise again," was powerless to console.

My sister Emma, the loveliest and most devoted of women, was suddenly called from this bright world in the summer bloom of her loving life, leaving four young and tender children, leaving all her relations and friends grief-stricken and myself in the depths of such anguish as only God and the good angels know. When we came into this world, it was in a large family of brothers who loved and petted the two wee girls with all the devotion of noble-hearted men. But they had long gone forth into the world, our noble parents had been called to their last home, while we remained together, our hearts throbbing in unison. Now that she was taken, it seemed to me there was a void that no space nor object of the affections could fill, and the better part of my life was gone.

In these darkened and burdened days of grief I can only tell how true, loving, and tender were the hands that ministered to me.

PORTAL IN SALTILLO.

The other members of our party were absent on a journey, and these strangers nobly filled their places. In the long and painful illness that followed, Pomposita, Liberata and other friends never left me for a moment, day or night, and in deference to my sorrow all were robed in somber black. Every possible delicacy that could tempt a wayward appetite was brought; notes and messages came daily to my door, and numberless inquiries, all expressive of sympathy and a desire to serve me, from the male relatives of my friends. These affectionate and tender attentions could not have been exceeded by those endeared to me by ties of blood.

Pomposita, though so young, as a matron took precedence, constituting herself my special nurse, in full accord with the Gospel injunction to love her neighbor as herself. In the fevered, silent watches of the night, how gently her soft little, brown hand would pass across my brow as she murmured her sweet words of endearment, and how lovingly her arms encircled me as she held me to her warm and noble heart. She constantly reminded me of her first visit and her assurance that she would be my sister.

In every way they all sought to win me from my grief. Indeed, it seemed that the ministering angels themselves had deputed their high mission to my devoted, faithful, and gratefully remembered Mexican friends.

In this land of sunshine and brightness there fell upon my heart the darkest shadow of my life, the shadow of the tomb of my sister, who slept the dreamless sleep in her far-off, lonely grave.