Face to Face with the Mexicans/Chapter 16

CHAPTER XVI.

SCENES FROM MY WINDOW.

The preponderance of the full-blooded Indian is noticeable in the lower classes; high cheek-bones, coarse, straight hair, the same sidewise trot, tipping from right to left, and all pigeon-toed.

The poorer classes all wear the serape, which, owing to its brilliant coloring, adds greatly to the effectiveness of a street scene. Many a housewife, artistically inclined, looks enviously at these beautiful wraps, and longs to drape them as curtain or portière.

Day by day, seated at my window, I watched the various groups that by some strange and happy chance seemed to fall together for my pleasure and entertainment.

The number and variety of articles which are transported by both men and women are certainly noticeable to the most indifferent observer. Young backs are early trained and disciplined, and the boys and girls bear burdens that might stagger a burro.

Clothes are taken home from the laundry in a droll manner. Men carry on their heads baskets containing the smaller articles, while suspended around the sides are stiffly starched, ruffled and fluted skirts, dresses and other articles of feminine apparel. In the rainy season the cargador has his trousers rolled up, so that there is nothing visible of the man but a pair of long, thin, brown legs.

CARRYING THE CLOTHES HOME.

I saw another man toiling along with an American two-horse load of corn husks on his back, held in place by ropes, the whole reaching from about a foot above his head down to his ankles, and almost closing him in, in front.

Venders of charcoal step nimbly along with from twenty to twenty-five bags of this commodity strapped about them, their bodies so begrimed as to render it hard to decide whether they belong to the Aztec or African race.

One obtains a glimpse of rural life in the frequent passing of herds of cattle, all without horns, and in the noisy gobbling of droves of turkeys as they are driven through the city. Halting only when their proprietor finds a purchaser, they strut through the streets of the metropolis as unconcernedly as though on their native hacienda.

Life seems to glide along very pleasantly with these people. As they pass along the street, they hail each other quite unceremoniously, the lack of previous acquaintance forming no bar to a familiar chat. Groups of more than a dozen of these venders, representing as many different commodities, will often congregate together, their forms almost concealed from view beneath their loads. Then, after a general hand-shaking, each goes his way, crying his wares.

POTATO VENDER.

The dispute became so violent that I expected as a result to see at least half a dozen dead Indians, but was disappointed.

The man who figured most conspicuously in the scene offered his hand to one of the women. She turned scornfully away, but I noticed, in so doing, she touched the arm of another woman and chuckled in an undertone. He spoke to another. She gave him one thumb only, looking shyly in his face. The next one gave him her whole hand, when he knelt and humbly kissed it, as though it belonged to his patron saint. Then, slipping her hand in his arm, and with her two little Indians, they walked off, leaving the rest of the party to a further discussion of the affair.

Then came a party of three—a huge dog, a grown boy, and an innocent muchacho about one year old. The dog was so loaded down with alfalfa that he could scarcely move. The big boy walked beside him, guiding him with lines. Mounted upon his brother's shoulders, with his feet around his neck, was the little mischief, holding tightly with both hands to a tuft of hair on each side of his big brother's head.

Diagonally across the street is the Theatre Principal. The play, "Around the World in Eighty Days," had for some time past occupied the boards. On the outside was an immense painting representing an elephant caparisoned with gold and led by an oriental, while mounted on the elephant, and seated after the fashion of a man, rode a woman dressed in gay colors, and over her a canopy with red draperies. Palms and other tropical trees appeared in the distance.

On the same canvas, and in contrast to this peaceful scene, appears another of quite a blood-curdling nature. A locomotive comes screaming and pufflng along. Suddenly myriads of wild Indians, painted red, with feathers on their heads and deadly weapons in their hands, make a furious attack upon it. They ride on the cow-catcher. Dead Indians and horses are piled around, and the headlight throws a ghastly illumination over all!

I witnessed a general review of the infantry troops in the city, a sight which was strictly national in its character, and made a showy and amusing picture. Mounted upon gayly caparisoned horses, the officers presented a handsome and soldierly appearance, in their uniforms of dark blue, elaborately ornamented with red and gold. The soldiers, neatly attired in blue, piped with red, and wearing pure white caps, were also quite imposing. But the sublime

BASKET-VENDERS.

I had scarcely recovered my equilibrium from the effects of the procession, when a carriage and horses came flying down the street in wild confusion. The Jehu sat bolt upright, with feet outspread from side to side, as if "down breaks" was in order. His eyes glared wildly from their sockets, as, with clinched teeth, he held desperately to the lines. The animals were evidently uncongenial to each other, one being a young mule, the other an unbroken pony. They reared and plunged violently, while Jehu used every expletive known to the Mexican language. But as this treatment proved unavailing, he jumped down from his lofty seat, and ran beside them, jerking the lines and screaming at them. Still they heeded him not. At this critical moment a sympathetic bystander conceived a fresh and vigorous idea of assistance, and as he ran along, jerked from the shoulders of an uninterested pedestrian (who had not even seen the runaway team) his red blanket, and waving it before the frightened animals, threw them trembling and panting on their haunches. In a twinkling Jehu was on the box, and, laying on the whip, was soon out of sight. I glanced across the street directly afterward, and saw a boy who had passed several times that day, selling butter, which he carried in a soap-box, the cover an odd bit of matting, and the whole suspended from his head in the usual way.

Entering the zaguan, he threw down his cage, and taking the butter out—each pound wrapped in a corn-husk—laid it in rows, and gave his head a scratch, took his money from his pocket, and began to count. Over and over he counted and scratched, evidently apprehensive that his accounts would not balance. The scratching and counting went on for no inconsiderable time, his face still wearing a puzzled expression. At last the solution came in the recollection of some forgotten sale. He rose, a broad grin overspreading his heretofore perplexed face, slapped himself on the hip, laughed, hastily slung his cage on his back, threw his blanket over his shoulder, and the last I saw of him he was vocalizing his occupation: "La man-te-quil-la" ("Butter for sale").

The gritos (calls) of the street venders become each day more interesting to the stranger. Each one is separate and distinct from the other, and each one is an ancestral inheritance. In them, as everything else, the "costumbres" rule, and the appropriation by another vender of one of these gritos would receive a well-merited reprimand. But how indescribable is the long-drawn intonation, with the necessary nasal twang of these indefatigable itinerants! A word with only four syllables stretches out until one may count a hundred.

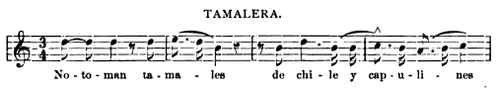

For the sake of conveying some idea of these street cries, I have with much difficulty procured the music of two or three of the leading ones. This is a branch of musical composition that has received but little or no attention from musicians, but by all means some effort should be made to preserve them in their originality, together with exact portraits of the venders as they now appear.

The gritos at the capital possess many interesting features which can be heard in no other city in which I have sojourned; they are wanting elsewhere in that fullness of pathetic and yet humorous melody.

The vocal powers, thus exercised, attain a surprising development, as the voice of an ordinary woman may be heard for squares away.

The most noted of all the female gritos is that of the tamalera, a description of whom appears elsewhere, an old woman from the State of Guerrero, who counts among her patrons many wealthy citizens.

No - to - man ta - ma - les de chi - le y cap - u - li - nes

The husky, tremulous voice of a young Indian woman fell upon my ear one morning as I was crossing the threshold of the San Carlos. Around her neck was a strip of manta filled with vegetables. On seeing me, she began importuning me to buy. They were fresh and crisp, but I said to her:

"I am a stranger; I have no home here, and have no use for such things."

"But, niña" she added, imploringly, "I am sick, have no home, and under these vegetables in the rebozo is my sick baby, only two weeks old."

Stooping to peep under the load of vegetables, there I saw the tiny babe, tucked away in the rebozo, and sleeping as soundly under its strange covering as though swinging in its palm-plaited cradle.

The mother asked me to stand godmother to the baby at the Cathedral, one week from that day, but as that was impossible, she seemed reconciled when she found her hand filled with small coins, and bidding me a grateful farewell, she went on her way singing her song of the "costumbres".

Com-pra usted ji - to-ma te, chi-cha-ros, e-jo - te, cal - a - ba - ci - ta?

Won't you buy tomatoes, peas, beans, pumpkins?

These gritos are rather more melodious than those to which our ears are accustomed, such as, "Ole rags 'n' bot-tuls!"

The melodramatic tones of the newsboys at night, when many of the most popular papers are sold, had a more foreign sound than any that came to my ear. The boy who sold El Monitor Republicano rolled it round and round his tongue until finally it died away like the hum of an ancient spinning-wheel.

Another boy, with an aptitude for languages, sings out, "Los Dos Republicos" (The Two Republics"), translating as he goes along, "Periodico Americano;" while another, not to be outdone, yells out exultantly, "El Tiempo de la mañana" ("The Times for to-morrow"). Only the word mañana was distinctly articulated, which gave emphasis to his vocation, as the Times is printed in the evening and sold for the next day.

An amusing admixture of sounds was wafted to my room one night in the following manner. Two boys were calling at the highest pitch. One was selling cooked chestnuts, and the other the Times.

They managed to transpose the adjectives describing their respective wares. "Castañas asadas" ('Cooked chestnuts"), shouted one. "El Tiempo de mañana, con noticias importantes" ("To-morrow's Times with important notices"), screamed the other. They were quite near together by this time, one on the sidewalk, and the other in the street; and when the air was again made vocal, a spirit of mischief had crept into the medley of sounds. The paper boy led off with mock gravity, "El Tiempo de mañana asada!" ("To-morrow's Times cooked!")

"Castañas de mañana con noticias importantes!" ("To-morrow's chestnuts with important news!") yelled the chestnut boy, and away they went, laughing and transposing their calls, to the amusement of all within hearing.

VENDERS OF COOKED SHEEP'S HEADS.