Folk-Lore/Volume 23/Ôḍikal and other Customs of the Muppans

ÔḌIKAL AND OTHER CUSTOMS OF THE MUPPANS.

BY F. FAWCETT.

(Read at Meeting, June 1st, 1910.)

The Muppans are a hill-tribe of Wynaad, Malabar. They live by cultivation and by collecting jungle produce. Their villages usually consist of a few huts of rude construction, but I have seen one in which there were about twelve in sets of four as near to each other as the uneven surface of the ground allowed. The huts, with the exception of a roof of grass thatch, are constructed entirely of bamboos, which, for the walls, had been opened out flat and, as it were, woven. As there is no plastering of mud, these dwellings must be very cold and comfortless in the monsoon. Each one is merely a covered-in room about twelve to fourteen feet in length and about eight feet high to the top of the ridge of the roof. The doors of some of the huts face south, while in Malabar generally houses never face the south,—the unlucky quarter where the dead are buried or burned.

Like most jungle people the men are familiar with the bow and arrow, but they are not regular hunters. On one occasion I saw a number of boys playing a game called Chôrâyyi, the players standing in a row and shooting with small bows and unfeathered arrows at a roughly-fashioned disc of bark which a man, standing some twenty yards in front and a little to the right of the row of boys, threw in front of them. The man threw the disc overhand, and, as it rolled and bounded along the ground in a line parallel to the players, the latter shot at it with their little arrows, and hit it often. It is therefore obvious that the men are habituated to the bow and arrow from childhood, even though they are not regular hunters; but, as we shall see presently, a Muppan sometimes finds it useful to be expert with these weapons.

During one of my visits to Wynaad I observed a small hut constructed high up and near the top of an immense clump of bamboos, some thirty feet or more from the ground. This was within a few yards of the hut of a Muppan which was itself somewhat removed from the little pâḍi, as a cluster of huts is called. The erection in the tree was said to be for occupation by the wife and three children of the Muppan, who was often absent. They slept in it for safety, as wild animals were numerous. It was reached by a very insecure-looking ladder, which was nothing but one long bamboo, the branches of which had been lopped off a few inches from the stem. As it seemed impossible that any human being could make such an ascent, a small boy was sent up to show me how. He went up with the greatest ease, much to my amazement.

The owner of these two establishments, one of which was useless without the possession of monkey-like agility and balance, was said to be the man who “kept the god”; so I went into the hut on the ground to have a look. The objects which were pointed out to me as representing “the god” were as follows:—A bundle of strips of bamboo, some three feet in length, bulged in the middle and tied at the ends; an axe; a bow; arrows; some ôḍikal sticks; a pair of stag’s horns. All, except the last, were objects for use. In another pâḍi not far off I saw objects just such as these, which were also said to represent “the god.” I thought at the time that the bundle was a fetish and protective, but it was evidently not completely so,—from the hut in the tree.

The explanation of the strips of bamboo tied in a bundle is this. A bundle was opened out for me. The bulge in the middle was due to there being in the centre of the bundle a number of small pegs cut something like a fork with one end longer than the other, by a few whacks from a jungle knife or chopper. On a certain day in the year, (known as Uchâl day in Malabar), following the death of a man, there is performed the following ceremony by the Muppans. So far as I know it is peculiar to them. A strip of bamboo is pegged out semicircularly on the ground, with three pegs such as have been described. Over this are placed some leaves of a certain tree, (which I have not, unfortunately, identified), and upon the leaves some rice and other offerings of food and liquor, if any is obtainable. These are, of course, for the benefit of the deceased. Then all the strips in the bundle are pegged out and treated in the same way. After some time the food is removed and eaten, while the new strip of bamboo with its three pegs is added to the bundle, which thus increases in size. The bundle is spoken of as Pennu mâri (ancestor people).[1] The strips of bamboo are used for men only, never for women, and for men only in the case of those whose moustaches have sprouted. It may be said that, like all the inferior races, hair grows, but never thickly, on the upper lip and on the chin a mere tuft, and never, or very, very seldom, on the cheeks. At all events, if a male has not attained manhood, indicated by the growth of some hair on his face, he is allowed no strip of bamboo, and, as in the case of the women, is given only the leaves and food.The Muppans' hair, it may be said, is worn Malabar fashion, shaved except on the crown, where the hair is long and tied into a knot. The wilder jungle tribes of Wynaad do not observe this fashion of hairdressing. The Muppans do not observe the custom usual in Malabar, among all Hindus as well as among all the lower non-Hindu races, for a man to allow his hair,—all the hair on his body,—to grow so long as his wife is with child.[2]

A woman is delivered in a small hut, erected for the purpose, a few yards to the south of the pâdi, and there she remains during the following forty-five days, having for company a woman of her own pâḍi. At the end of this period she bathes in a stream, washes her clothes, receives new ones, and after "holy water" (brought from the nearest Hindu temple) has been sprinkled over her and over the little shed, she returns to her hut, purified of all pollution.

Conversation turning towards the subject, I endeavoured to elicit from some Muppans what they considered to be downright bad,—the worst action a man could be guilty of. They seemed rather clear on the point; and yet, perhaps, there was misunderstanding on both sides. At all events, they were cocksure the worst act a man could do was going too near a Hindu temple. Restrictions as to approaching the person or even the dwelling of a high caste man, or a Hindu temple, in Malabar are very strictly observed, and under these unwritten rules no Muppan is ever allowed nearer to a Hindu temple than ten yards from the outer wall which encloses the temple grounds. Should a man happen to trespass against this rule, snakes are sent to annoy him,—to punish him.

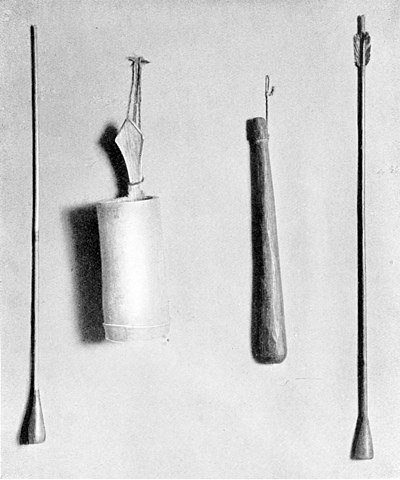

We now come to ôḍikal. Oddly enough its existence became known for the first time about fifteen years ago, through a case which was eventually tried in the usual way in our courts, and this case arose out of the unprecedented circumstance of a Muppan having learned to write. He was the first and only Muppan who had ever learned to write at all. This pioneer in knowledge had acquired the Malayālam, the vernacular alphabet, and was able to write simple words and names; and so it was that, when his uncle, a victim of ôḍikal, at the point of death revealed the names of the men who had killed him, he wrote their names on a piece of paper. Then there was a case of murder. Up to this time every Muppan kept in his hut a couple of ôḍikal sticks (Plate I.), just in case they might be wanted for an enemy. Then they disappeared as if by magic, and could not be procured for money. I was, however, able to secure two genuine ones. They were obtained at the very place where, so far as we know, the last ôḍikal deed was done, where, indeed, I made my camp in a lonely glade in the bamboo jungle, and where the whole story of the process of ôḍikal was, in course of time and patience, revealed to me.

It was not made quite clear what offences on the part of an individual rendered him liable to death by ôḍikal. Certainly intriguing with another man's wife was one of them, because it was this which led the last victim to his fate. Mere suspicion, or even proof as we understand it in law, is not sufficient to establish a case of ôḍikal: there must be definite demonstration to the extent of ocular proof. When this has taken place, the aggrieved husband may consult the men of his own pâḍi, who are always related, whether the other man should be killed by ôḍikal; and, if he is unable to convene a satisfactory consultation among those of his own pâḍi, he calls in relatives from elsewhere. Women are never consulted, nor is the subject ever mentioned to them. The conclave considers the whole affair in secrecy, and arrives at a decision whether the other man deserves death by ôḍikal. Decision for death cannot be made without the unanimous consent of the men present. Sometimes the verdict is that the offence is not worthy of death, and then there is an end of it. Or it may be that the risk is too great. If death is decided upon, a bow is at once made to the ancestors and to Wulligan and Kuttichâthan, promising the sacrifice of a cock and offerings of other food when all has concluded satisfactorily, [Wulligan, a Malabar "devil," is accused of causing pains to men and women, pressing their necks while sleeping, and calling out and frightening people,—all for the fun of the thing,—while Kuttichâthan, an exceedingly mischievous spirit, sets fire to thatched houses and straw ricks, and is specially annoying to small boys.] The Muppans believe that these two unpleasant beings lord it as gods over their ancestors. So familiar are they in Malabar that anyone will tell you what they look like, even to the length of their hair. Most fearsome to look upon, it is, indeed, mainly by their hair that one is distinguished from the other, for they do not observe the same fashion, one dressing his in a curious crown arrangement some five cubits above his head, while the other adopts a style resembling the Prince of Wales' feathers, the centre pinnacle reaching to 20 cubits in height. These weird spirits, to whom are imputed almost every possible kind of personal calamity which cannot be accounted for at once and obviously throughout the low country, the littoral in Malabar, are the gods of the Muppans' ancestors. It is to be noted that neither the ancestors nor their gods are ever consulted as to whether the particular offence in question deserves punishment by death; they are simply invoked for help under promise of fresh blood and other food in case of success.

The best days for ôḍikal are Sundays, Tuesdays, and Fridays, the luckiest days. The man to be killed is watched, and opportunity is taken by the plotters, who are as a rule three to five in number, to come upon him while alone in the forest. He is brought to the ground by a well-aimed blunt arrow (Plate I.), striking him on the back of the head. This shot is easy of accomplishment, as the Muppans wear no turbans, but one directed to the middle of the backbone, (as they are not clothed above the waist), or on the sternum answers the purpose equally well. As soon as their victim has fallen, the men engaged in the deed run up to him and stuff a cloth into his mouth,—to prevent him from calling out when he comes to,—and carry him, while still unconscious, to a convenient place, where they are not likely to be molested,—for the operation to be performed takes some time. He is held firmly, lying flat on the ground, face upwards, while one of the party, standing over him, hits two smart, but not severe, blows on his right elbow, the outside of the joint; then on the left elbow, in precisely the same manner; then on the right knee-cap; and then on the left knee-cap. He is turned on his left side, and, while the right arm is raised, he is given several sharp blows on the ribs, beginning under the armpit and working downwards. His left side then receives similar treatment, he being turned on his right side for the purpose. Next he is turned over on his face, and, with the thick end of the stick, he is dabbed outside the shoulder blades, working downwards, first the right and then the left. The next blow, one only, is administered to the small of the back. The victim is then turned on his back, and is dealt one blow on the sternum. His chin is slightly raised, while one smart blow falls on his Adam's apple. The outside point of the right ankle joint is then tapped sharply with the stick,—I am not sure whether once or twice, but probably only once; then the left one. He is then raised to a standing position, and given one good dab in the abdomen, and one whack on the top of the head. All this torture which has been described is done deliberately, without any hurry whatever, great care being taken to deal out the taps neatly and precisely, exactly on the right spot. When it is all over, the victim is made to swear that he has not been beaten at all. He is made to swear "by the god above and by the earth below" that he will never reveal the names of his murderers, and he is at the same time informed that, if he should do so, every member of his family will be treated in the same manner, one every year. It may be that, deeming his answers unconvincing, the death dealers will not trust him, and in such a case they make sure of their own safety by damaging their victim's tongue with thorns in such a way that he is unable to speak. This last piece of devilment was said to be resorted to but seldom. They have now done with him, and, if his pâḍi is not far off, they allow him to walk thither alone. If, however, it is at some distance, and he is suffering from exhaustion, they help him along in a friendly way until he is near enough to reach it unaided.

The wretched man reaches his home knowing well that his death will take place without fail within seven or eight days. In the case which I was able to examine, ôḍikal took place on a Tuesday, and death took place on the following Monday. Kêlu, the victim, was supposed by his family to be suffering from fever, common enough in that malarial district, accompanied by intense pain, until the Saturday, when the appearance of some slight swellings made them at once aware of the truth. He was unable to swallow nourishment in any form, and, racked with pain, sat on the ground holding his hands behind his head. Just before he died, coming back to his senses after a long swoon, he was able to hold up one hand, the fingers distended, and with much difficulty enumerate five names. That was all. His nephew, who was constant in attending upon him and the first Muppan possessing any literary aspirations, at once wrote these names on a scrap of paper. Thus the ôḍikal came under the notice of the local officials, with the result that a charge of murder was launched.

The injuries caused by the taps, dabs, and whacks by the ôḍikal stick which have been described could not have been very obvious, because the medical officer, a subordinate of the government medical department, who held the post-mortem, certified that death was due to inflammation of the lungs. Very likely he had suffered in that way. The local rainfall is very heavy. I have myself known fifty-two inches of rain to have been measured in three days on a coffee estate close by. Rain such as this, accompanied by a howling wind, is, perhaps, likely enough to affect the lungs of people who are almost unclothed, who even in the cosiest corner of their dwelling are only very partially protected from it. It is cold and damp to the last degree during the south-west monsoon in the Wynaad, which lies at an elevation of about 3000 feet above sea level. The autopsy was faulty. Death was certainly due to ôḍikal. I was informed that a victim to ôḍikal never, under any circumstances, lived after the eighth day. Death followed inevitably, and, as a rule, on the sixth or seventh day.

Having made sure of their victim's death, and feeling confident that he dare not, or at all events will not, disclose their names, his tormentors quietly return to their pâḍi. The cock is sacrificed inside the hut, close to, but a little to one side of, the bundle of bamboo strips of which mention has been made already. Rice is cooked, and so is the fowl, and both are eaten. As a preliminary to the sacrifice, it should be said, some two or three of the strips are pegged out in the usual way. It is rather indefinite, but the Muppans appear to believe that in some way their ancestors take possession of their victim as soon as they have treated him to ôḍikal. They have their ancestors "in mind" during the whole affair, and their victim would appear to be considered in the light of a sacrifice to them. But why in this extraordinary manner? It was extracted from them that ôḍikal causes the blood to circulate the wrong way, and thus brings death. But, of course this belief offers no explanation why this peculiar method of taking an enemy's life should be resorted to. Let me add further that, should it by any means whatever become known to the family of the victim that he died by ôḍikal, it is their solemn duty to retaliate, beginning with the head man among the murderers, removing one every year. A regular vendetta begins in this way.

A few more words may not inappropriately be added on the death ceremonies of the Muppans.

When a man is at the point of death, a little rice and râgi (a millet) are put into his mouth, and also a small silver coin, if one is available. The corpse is washed, and clothed with a fresh cloth. It is carried on a flat mat-like bier feet foremost through the door and all the way to the place of burning, where it is carried thrice round the funeral pyre before being placed upon it. Very likely the last-mentioned feature in the ceremony has been borrowed from the Hindus. Green logs of a certain tree (valuga maram in the vernacular), are used for consuming the body by fire. The head is placed towards the south. Fire is applied by the headman, while the relatives stand close by. When the body has been burnt, the widow gives to each person present a little rice, sprinkling it with water as she does so, and every one throws the rice on the burnt pyre. Any ornaments which may have been worn by the deceased, and which are of the commoner metals, (but never if of gold), are left untouched. Every one then leaves the place, walking to the pâḍi without looking back. The pâḍi may be in any direction, as it is immaterial on which side of it a corpse is cremated. As they enter the pâḍi, a bamboo vessel (Plate I.), containing water in which a little cow-dung is mingled, is placed conveniently, and every one, the headman leading, sprinkles a little of this mixture to right and left, while the last man sprinkles all that remains around the pâḍi. Râgi, but not rice, is eaten on this day. Râgi, it should be said, is the coarser commoner food of the two. On the following day no one works; they merely bathe, and their food consists of râgi only. On the next day anything excepting fish may be eaten; and death-pollution is for the present at an end. The nearest of kin to the deceased,—e.g. for a wife a husband, for a brother a brother, for a father a son,—allows his hair to grow until completion of the final ceremony which removes every trace of pollution and gives peace to the departed spirit. This growing of the hair is also probably an innovation borrowed from the Hindus.

The final ceremony may take place within a few days or after the lapse of months, for the governing factor is simply expense. Relations from other pâḍis are invited, and they may bring their friends. The opening day for this ceremony must be a Monday, on which day the people simply foregather and have a good feed. Next day all go to the spot where the corpse was burned. Some earth is strewn over the ashes, and, with the end of a stick, the full-length figure of a man is drawn. A hole to the depth of three feet is dug just over the head, and into it are put, (1), seven silver coins of small value, (or a small silver ornament if there are no coins to be had); (2), four bones which have been taken from the ashes, which are supposed to represent the hands and feet, and are washed; (3), a small quantity of rice and râgi; and, (4), one of seven bundles of rice which have been prepared. The hole is covered over with leaves, and, in order to preserve its contents from contamination by falling earth, a small platform of sticks and stones is fixed above them. Upon this little platform are placed the six remaining small bundles of rice, earth is thrown in, and the hole is filled up. On the surface, there are placed small thorny branches, probably for the purpose of discouraging the dogs which, having to find their own living, might be inclined to dig up the food. When returning to the pâḍi, after bathing, the ceremony with the cow-dung water is again observed. Some rice is then cooked. The deceased's widow sits on the ground outside her hut, and beside her is placed a winnowing-basket in which is some of the cooked rice, and a bamboo vessel or a coco-nut shell containing water. A large mat is then placed right over the woman, the winnowing-basket, and the vessel of water. She sprinkles the water, rises, and enters the house, where a quantity of food has been already prepared for the deceased. The headman distributes the cooked rice which was in the winnowing-basket to the visitors who are friends of the family, while the widow and the nearest relatives eat the food which is in the hut on behalf of the deceased. On the following Uchâl day the deceased is represented by a strip of bamboo pegged out in the manner which has been already described.