Fugue (Prout)/Chapter 8

CHAPTER VIII.

STRETTO.

244. The word "Stretto" is the past participle of the Italian verb, "stringere,"—to draw close. It is occasionally used in music other than fugues as equivalent to the present participle of the same verb, "stringendo," in the sense of pressing on, or hurrying up the time; but when employed, as it mostly is, in connection with fugue, it is the name for that part of a fugue in which the entries of the subject or answer follow one another at a shorter distance of time than in the first exposition.

245. Most theorists name the stretto as a necessary part of every good fugue. Cherubini speaks of it as an "indispensable condition" and an "essential requisite"; and he adds that "a good fugal subject should always give scope for an easy and harmonious stretto." But this rule, like most others given in the old text-books, will not stand the test of applying it to Bach's practice. Out of the forty-eight fugues in the 'Wohltemperirtes Clavier,' more than half have no stretto at all; and of the remainder some have only a fragmentary, or partial one. If a stretto is really an essential part of a fugue, then it is evident that more than half Bach's fugues must be badly written. The simple truth is, that it is not Bach's workmanship, but the rule that requires to be altered. Any rules regarding fugue, which will not fit the works of the greatest fugue-writer that the world has ever seen, carry their own condemnation on their face.

246. Instead, therefore, of laying down a law that every good fugue must contain a stretto, we maintain that, though often a most valuable ingredient of fugue writing, it is never absolutely indispensable. In the 'Wohltemperirtes Clavier' some of the fugues which have no stretto (e.g., Nos. 2, 12, 21, and 40) are among the finest and most perfect works of art of the whole collection.

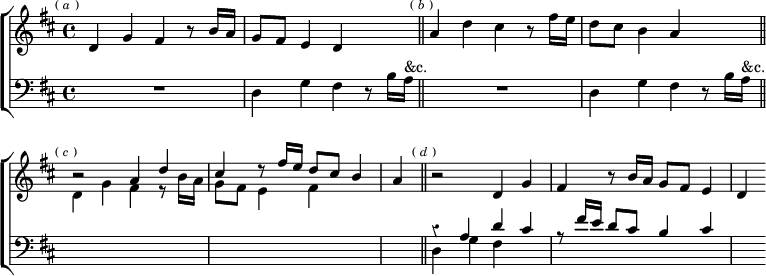

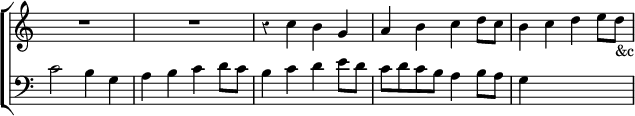

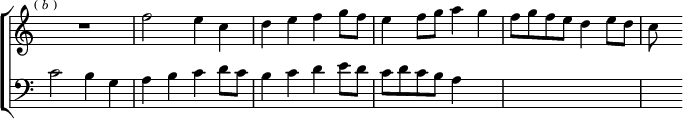

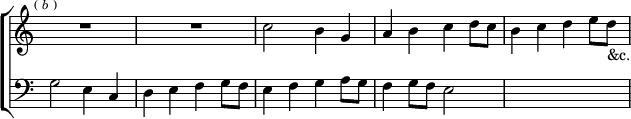

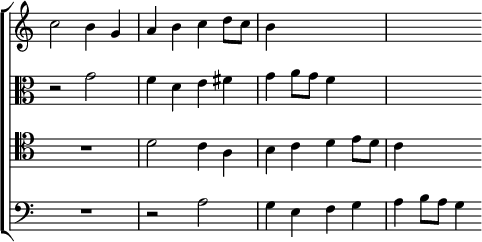

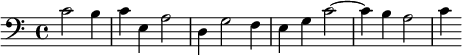

247. It is by no means every fugue subject that adapts itself easily and naturally to the purposes of stretto. A subject intended for this should be expressly designed for it in the first instance; otherwise there will most likely be a certain stiffness or harshness about some of the imitations. For example, in writing the fugue subject of which we gave expositions in §§ 194, 204, it did not happen to occur to us to make one which would be suitable for stretto afterwards. Consequently, though it is quite possible to introduce later entries at a shorter distance than two bars, these will not be so effective, nor flow so naturally as if the subject had been written with this object in view. We give a few stretti as illustrations.

248. These examples, which must not be regarded as models of a good stretto, but are written to show that a stretto of some kind is mostly possible even for a subject not at first designed for it, illustrate several points relating to its construction. We see at (a) a case of common occurrence. Here the imitation is not in the fourth or fifth, but in the octave. As a matter of fact, the imitation in a stretto may be at any interval, though in general those in the fourth, fifth, and octave will be found the best. At (b), as at (a), the imitation is at one bar's distance; but it is here in the fifth below; the answer leads, and the subject replies. The imitation of the answer by the subject often gives a different set of combinations.

249. At (c) the subject leads and the answer replies at half a bar's distance. The consecutive fourths between the first and second bars are bad, as they stand;. but a stretto for two voices, like a two-part double counterpoint, is mostly accompanied by free parts. Here we have left the bass staff empty, instead of putting rests, to show that a bass is meant to be added, which will make the fourths right. Observe that the last note of the subject has to be changed here, to avoid consecutive octaves.

250. Our last stretto, at (d), is also the closest. It is for three voices at one crotchet's distance. It is evident that now the bass cannot possibly complete the subject; it will therefore have to continue with a free counterpoint, which we have purposely not filled in, so as to show only the close imitations. The middle voice now has the subject, per arsin et thesin, and, as at (c), the last note requires to be altered.

251. Before writing a subject specially to show the different possibilities of stretto, it will be well to give a few general hints for the guidance of the student. We said in § 248 that a stretto might be at any interval; to this we now add that it may be in any number of parts. If a stretto is employed in a fugue at all, we generally find more than one; and in that case, in order that the interest of the music may gradually increase, we mostly find the later stretti either in more parts or at a shorter distance of entry, or both, than the earlier ones.

252. It is not always possible for the voices which enter first in a stretto to continue the subject after another voice has entered. This was shown in § 247 at (d), where the bass had to discontinue the subject on the entry of the treble. Though it is best to carry on the imitation as far as possible, it is always allowed to break off the subject, or to modify it after another voice has taken it up. But it should be remembered that the last entering voice in a stretto should have the subject complete. We of course use the words "subject" and "answer" indifferently here, as the entry may be at any interval.

253. From the same consideration—that of freedom of interval in the entries—we are allowed in a stretto of a tonal fugue to employ either subject or answer, as may be more convenient. The imitations in a stretto may also be by augmentation, diminution, or inversion, or (as we saw at (d) § 247) per arsin et thesin.

254. We will now write a subject and answer adapted for stretto, and then show some of the numerous stretti of which it is capable.

As there is here in the subject an implied modulation to the dominant, the answer will be tonal. In accordance with the rule given in § 121, we regard the modulation as being made as early as possible—here, after the first note of the subject. The answer enters at the beginning of the fifth bar.

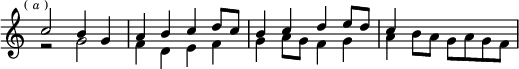

255. We will first try to bring in the answer as near the end of the subject as we can. Clearly if we keep the tonal answer, we cannot introduce it in the fourth bar of the subject.

This is manifestly impossible, though the addition of thirds below the answer would render it practicable. But we said in § 253 that it was allowed to use either form of the subject in the stretto of a tonal fugue. It would therefore be quite feasible to introduce the answer against the last bar of the subject thus—

As this passage is written in double counterpoint in the octave, the answer could also be introduced above the subject.

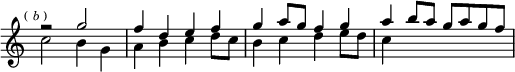

256. We will now reduce the distance of entry by half a bar, bringing in the answer, per arsin et thesin, on the second half of the third bar.

The student will see that at this distance of entry, it is impossible to complete the subject. Note also that in consequence of the bare fifth at the end of the third bar this stretto cannot well be inverted as the last one could.

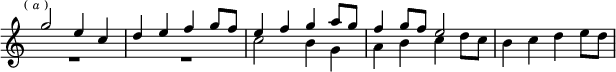

257. If we next try to make a stretto with the answer at two bars' distance, we shall have either to discontinue or to modify the subject on the entry of the answer.

It would, however, be possible here to continue the subject unchanged to the end, if we make the imitation in the octave instead of the fourth. We shall have to shorten the first note of the imitation (§ 57).

This stretto, like that in § 255, will also invert in the octave.

258. At one bar's distance we can get a stretto in the fifth below.

We might here also have preserved the tonal form of the answer by treating the A in the second bar as an accented passing note.

In the fourth bar we have varied the rhythm of the imitating voice, to retain the subject in the leading voice for half a bar longer. Obviously we could not write

Such slight modifications, either of rhythm or melody, are very common, and always permissible in a stretto. We now give the inversion of the above.

259. Lastly, we can make a stretto with this subject at only half a bar's distance.

Like most of the preceding, this stretto can be inverted in the octave.

260. If now we begin with the answer instead of the subject, we shall obtain a different series of stretti, though resembling those already given in their general character.

Here the subject enters three bars after the answer. We give the inversion.

261. We next show the answer followed by the subject at two bars' distance.

It will be seen that the leading voice cannot here continue the subject to the end. This imitation inverts as follows—

262. At one bar's distance the answer cannot be comfortably imitated by the subject. Here, therefore, we make the imitation in the octave; and even at this interval we cannot continue it long.

263. At half a bar's distance, it is possible to reply with the subject, and the imitation can be continued somewhat farther than in the last example.

The above will also invert—

264. Hitherto we have only given stretti in two parts; but the subject we have chosen will also work in stretto in three or four parts in many different ways, We give two specimens in three, and two in four parts.

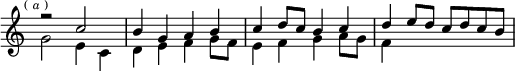

Here is a simple example, in which each part follows at a distance of one bar. The intervals of entry are irregular; the alto being a fifth below the treble, and the bass a seventh below the alto.

265. In our next example,

the intervals of entry are the same as in the last; but a quite different effect is produced, because now the answer leads and the subject replies; and, besides this, the distance of time in the entries is irregular, the second voice being two bars later than the first, and the third voice only one bar later than the second.

266. In our first four-part example,

the entries are regular as regards distance of time (one bar), but irregular as to interval. In this stretto it is not possible in any of the voices (except, of course, the bass which is the last to enter, and in which it should be complete—§ 252) to continue the subject to any great length.

267. We lastly give the closest possible stretto in four parts.

Here the entries are regular both as regards time and interval, each succeeding voice being introduced half a bar later, and a fourth below the preceding one. It will be noticed that in each voice the subject is carried down to the same point.

268. We have now given more than twenty stretti on the same subject, of which we have by no means exhausted the possibilities. It is probable that, by using all the combinations in three and four parts at the various distances of time and entry, we might make at least forty or fifty stretti on this subject. The student may not unnaturally be inclined to ask, What is the difference in character between this subject and the one worked in § 247; and how is it that so few good stretti could be obtained from the one, and so many from the other? The explanation is very simple. We said in § 247 that a subject intended for stretto should be expressly designed for that purpose. The best and easiest way of so designing it is, to write it in the first instance as a canon in the fourth or fifth at the shortest distance at which it is intended ultimately to be introduced. In the present instance we began by composing the little canon seen at § 259 (a), as far as the first note of the fourth bar. We then completed the subject by the addition of the notes—

The entries at longer distances were then found by experiment—trying to fit the answer against the subject, or the subject against itself, at all possible intervals and distances of entry. It will nearly always be found that subjects which, like this one, work in close stretto, can also be employed at longer distances.

269. The stretto is mostly met with in the middle and final sections of a fugue, of which we shall speak in the next chapter; but when the fugue has a counter-exposition, the first stretto (as already mentioned in § 209) is frequently introduced at that point. A good illustration of this is seen in the 33rd fugue of the 'Wohltemperirtes Clavier.' We quote the exposition and the counter-exposition.

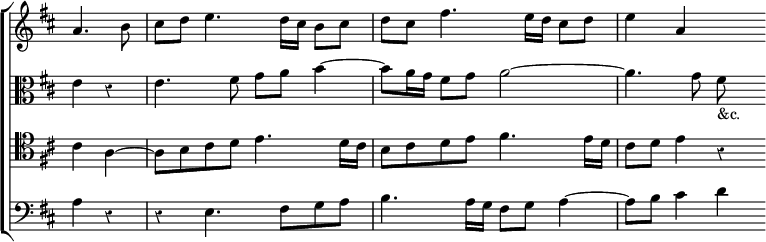

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 33.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber.break-visibility = ##(#t #t #t) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff \relative b' { \key e \major \time 4/2 \bar ""

R\breve*4 r1 \[ b1^"A" | cis2 e dis cis |

b1 ~ \] b4 a8 gis a2 ~ | a gis fis e | dis r r1 | R\breve

\[ e1^"S" fis2 a | gis fis eis4 \] fis gis a }

\new Staff \relative e' { \clef alto \key e \major

R\breve*3 e1^"S" fis2 a | gis fis e r4 \[ b^"CS" |

e fis gis ais b8 fis b2 \] a4 ~ |

a gis8 fis gis2 cis,2. dis8 e | dis2 e ~ e4 dis cis2 |

fis, \[ b^"A" cis e | dis cis b4 \] e2 dis4 ~ |

dis cis2 b8 ais b4 fis'2 e8 dis | e2. dis4 cis1 }

\new Staff \relative b { \clef tenor \key e \major

R\breve r1 \[ b^"A" | cis2 e d cis |

b2. \] \[ b4^"CS" a b cis dis | e8 b e2 \] dis4 e2 gis,4 fis |

gis2 e fis1 ~ | fis4 b, e2 ~ e4 cis fis2 ~ |

fis4 \[ e8 fis gis4 a b8 fis b2 \] ais4 | b2 r \[ e,1^"S" |

fis2 a gis fis | e4 \] a2 gis4 fis4 \[ e8^"CS" dis e4 fis |

gis a b8 fis b a \] gis2 fis^"&c." }

\new Staff \relative e { \clef bass \key e \major

\[ e1^"S" fis2 a | gis fis e4 \] dis8 cis dis4 \[ b |

e fis gis ais b8 fis b2 \] a4 ~ | a gis8 fis gis2 ~ gis fis |

gis a4 b8 a gis4 fis e dis | cis1 b2 fis |

gis2. e4 a2. fis4 | b\breve ~ | b2 r r1 | r \[ b^"A" |

cis2 e dis cis | b1 ~ \] b2 a } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/p/z/pzajxpwt2cro2bwmbvvhm5zpkl9oitb/pzajxpwt.png)

The bars are numbered for convenience of reference. Note the altered forms of the countersubject spoken of in § 170. The exposition ends at the beginning of the seventh bar. The two bars that follow have hardly enough distinct character to constitute an episode; they are rather a kind of codetta—a prolongation of the exposition, leading up to a half close, to introduce the counter-exposition. Here we see (§ 207) that the voices which before had the subject (the bass and alto) now have the answer, while the tenor and treble have the subject; we also see the entries in a rather close stretto. It looks at first as if the introduction of a close stretto so early in the fugue were premature; but Bach has other devices in reserve for the later part of this fugue, as we shall see presently.

270. In the 31st fugue of the same work, the counter-exposition contains a canonic imitation in stretto, first between tenor and bass, and then between alto and treble. We quote the passage; the subject and answer of the fugue were given in § 88.

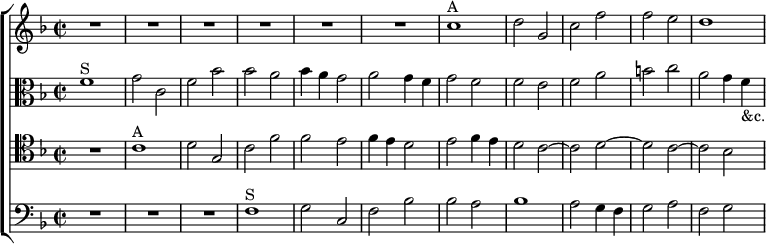

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 31.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

\new Staff \relative b' { \key ees \major \time 2/2

bes4 d8 ees f4 d | bes ees8 f g4 ees | f ees8 d c4 d |

ees r r2 | R1*4 \[ ees1^"S" bes'2 r4 aes | g c2 bes4 |

aes aes8 g aes4 c | f, bes2 aes4 | g g8 f g4 bes | ees, \] }

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef alto \key ees \major

d4 f8 g aes2 ~ | aes4 g8 aes bes4 g | f bes aes bes |

bes, r4 r2 | R1*3 \clef treble | \[ bes'1^"A" ees2 r4 ees |

d g2 f4 | ees ees8 d ees4 g | c, f2 ees4 |

d4 d8 c d4 f | bes, \] bes8 aes bes4 d | g,_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative b { \clef tenor \key ees \major

bes2 \[ bes^"A" ees r4 ees | d g2 f4 | ees ees8 d ees4 g |

c, f2 ees4 | d d8 c d4 f | bes, \] bes8 aes bes4 d |

g,2 g' ~ | g4 g8 f g4 a | bes d,8 c d4 f | g g8 f g2 ~ |

g4 c, f2 ~ | f4 f8 ees f2 ~ | f4 bes, ees r | r }

\new Staff \relative b, { \clef bass \key ees \major

bes2 r | r \[ ees^"S" | bes' r4 aes | g c2 bes4 |

aes aes8 g aes4 c | f, bes2 aes4 | g g8 f g4 bes |

ees, \] ees8 d ees4 g | c,2 c' | bes4 bes8 aes bes4 d |

ees2 r4 e | f f,8 e f4 a | bes2 r4 d | ees ees, ees'8 d c bes | c4 } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/p/5pep6ai7qxldneqzrc2pcudu2g5pah9/5pep6ai7.png)

Here, as in our last example, the answer leads and the subject replies; but a deviation is made from the usual practice, inasmuch as the tenor, which had the answer in the first exposition, has it again here, and the bass (as before) has the subject; but with the other pair of voices, the usual plan is followed, the alto now giving the answer instead of the subject, and the treble giving the subject instead of the answer. The irregularity is probably due to the fact that Bach intended to invert the canon on its repetition by the upper pair of voices. Canonic imitation in stretto is not uncommon in a fugue; the student will see other instances of it in Nos. 20 and 46 of the 'Wohltemperirtes Clavier'; but it is seldom met with so early as in the counter-exposition; more frequently we find it in the middle or final section of the fugue.

271. Though, as has been already said, the imitations in a stretto may be at any interval, it is generally advisable to observe some kind of order in the entry of the different voices. Our next example will illustrate this point, as also that mentioned in § 252, that one voice in a stretto may discontinue the subject as soon as another voice enters with it, but that the last voice that enters should complete the subject. The student will find the subject, answer, and countersubject of this fugue in § 169

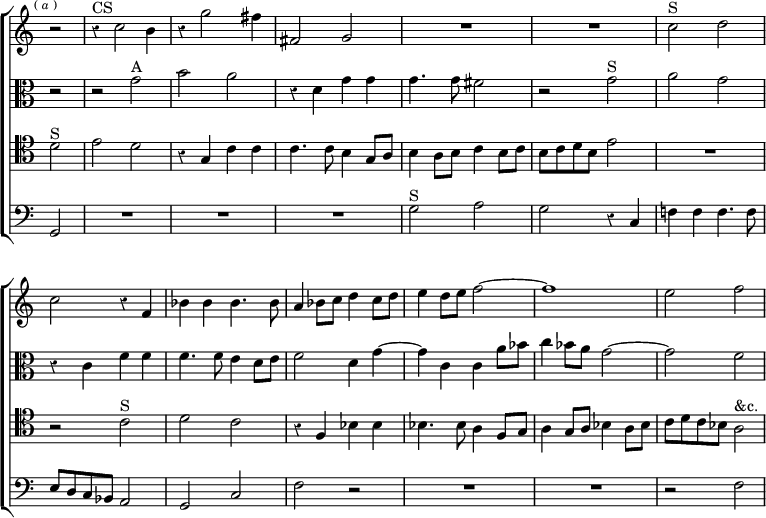

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 24.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff \relative f' { \key b \minor \time 4/4

fis8 \[ fis'^"S" d b g' fis b ais |

e dis^\markup \teeny "incomplete" \] r e ~ e16 dis e g fis4 |

e16 d! cis! b a b cis e d b cis e fis d e gis |

a g fis e d cis b a g e fis a b g a cis |

d e d e fis g a fis d f e d c b c d |

c b8. a4 ~ a8 d16 e fis g a, gis e' fis g,! fis s8 }

\new Staff \relative b' { \clef alto \key b \minor

b8 ais r b ~ b16 ais b d cis4 |

r8 \[ b^"S" g e c' b e dis |

a gis^\markup \teeny "incomplete" \] a4 ~ a8 gis c b |

e r r fis, d4 r8 g |

a d c4 b a ~ | a8 a16 gis a g fis e d cis b cis d4 | c4 s8_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative a { \clef tenor \key b \minor

R1*3 r8 \[ a^"S" fis d b' a d cis |

g fis ees' d a gis f' e | dis e cis a b2 | b8 a4 \] }

\new Staff \relative f { \clef bass \key b \minor

fis16 e d cis b cis d fis e cis d fis g e fis ais |

b a! g fis e fis g b a fis g b c a b dis |

e8 \[ e,^"S" cis a fis' e a gis |

d cis^\markup \teeny "incomplete" \] d2. ~ d4 r r2 R1 r4 s8 } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/l/klm8y0ysnbkzldy0774dvj5nayr25nt/klm8y0ys.png)

Here the entries are at a regular distance of one bar after each other; the alto is a fifth below the treble, the bass a fifth (twelfth) below the alto, and the tenor the fourth above the bass, which is the inversion of the fifth below. Each voice, except the tenor, which is the last to enter, discontinues the subject when the next voice enters with it. In the fifth bar of the extract is seen a fragment of the acountersubject in the alto, which, in the following bar, is continued by the treble. It is not uncommon in the middle section of a fugue to find a countersubject begun by one voice and completed by another. It should be noticed that the counterpoint of semiquavers, seen first in the bass and then in the treble, is developed from the codetta in the fourth bar of the example in § 169, before the entry of the countersubject.

272. Sometimes not only the subject, but the countersubject of a fugue is used in a stretto. A remarkably fine example of this is seen in the great five-part fugue in C sharp minor of the 'Wohltemperirtes Clavier.' It will be remembered that this fugue has two countersubjects, both of which we quoted in § 172. Only the second one, shown at (b) is employed with the subject in the stretto. Though the passage is rather long, it is so interesting, and deserves such careful examination that no apology is needed for quoting it in full.

It would occupy too much space to analyze this passage fully. The student, with the aid we have given him by marking all the entries, will have no difficulty in doing it for himself. But this extract illustrates a point we have not yet had occasion to notice. It contains two pedal points, first dominant and then tonic. These, the former especially, are not seldom to be met with toward the close of a fugue, more particularly with vocal fugues; and when they are found, it is very common also to find close stretti built above them.

273. A stretto may be made from only a part of the subject of a fugue, with a new continuation. The "Amen" chorus of the 'Messiah' furnishes a familiar illustration of this; the subject of the fugue is too well known to need quotation.

Handel. 'Messiah.'

Here the first five notes only of the subject are taken for the stretto, the continuation of the passage being new. The stretto is at one crotchet's distance in all the voices, and is in reality a canon 4 in 1, at the octave and fourth below.

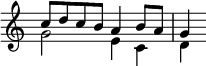

274. A fugue subject may also in a stretto be taken by inversion, augmentation, or diminution, or any combination of these, instead of in its original form. No rules can be given as to when these devices should be employed; this must be left to the judgment of the composer. We give a few examples. The subject of the 6th fugue in the 'Wohltemperirtes Clavier' is the following—

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 6.

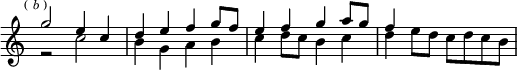

The answer enters in the third bar. In the course of the fugue we meet with the subject slightly altered in form (a major third being substituted for a minor), and imitated at one bar's distance by its own inversion.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\new Staff \relative b' { \key d \minor \time 3/4 \mark \markup \tiny { (\italic"b") }

bes8 \[ a^"S" b cis d b | cis16 a gis a f'4 d\trill |

e8 \] a ~ a16 g fis e g fis e d | ees c' bes8 }

\new Staff \relative c' { \clef alto \key d \minor

cis4 d8 e a,4 | r8 \[ e'^"S (inverted)" d cis b d |

cis16 e fis e a,4 c | bes16 d ees d }

\new Staff \relative a { \clef bass \key d \minor

a4 ~ a16 g f e g f e d | e8 cis d e f d |

a'4 fis8 e d fis | g4 } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/1/q/1q5hcehi838yraivxvnmxlppggwifmy/1q5hcehi.png)

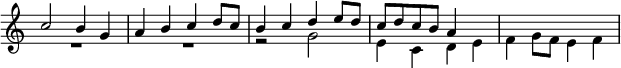

Later still all three voices of the fugue take part in the stretto, the inverted subject now leading.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff \relative c'' { \key d \minor \time 3/4 \mark \markup \tiny { (\italic"c") }

cis8 \[ a'^"S (inverted)" g f e g | f16 a bes a cis,4 e ~ |

e8 a, d4 \] c! | c8 ees ~ ees16 d c d d c bes c | c bes a bes }

\new Staff \relative f { \clef alto \key d \minor

g4 r r | r8 \[ d'^"S" e f g e | f16 d cis d b'4 g |

a \] fis, a | r16 g fis g }

\new Staff \relative e { \clef bass \key d \minor

e4 ~ e16 d cis b d cis b a | d4 r r |

r8 \[ a'^"S (inverted)" g f e g | fis16 a bes a d,4 f | g, \] } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/8/2/82qd26ia7bkd0arx0c0sj5drw554wvr/82qd26ia.png)

275. Our next example, also in three parts, shows augmentation of the subject, as well as inversion.

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 8.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

\new Staff \relative e' { \key dis \minor \time 4/4 \partial 2

eis4 r8 bis' | cisis dis eis4 ~ eis8 dis cis16 b cis fisis |

gis ais b4 ais16 gis ais8 dis, eis fisis |

gis4 r \[ ais^"S (inverted)" dis, ~ | dis8 b cis dis eis dis cis4 |

gis' dis ~ dis8 eis fisis4 | gis8 \] ais gis fis eis dis gis4 ~ |

gis8 fis eis fis16 gis ais gis ais4 gis16 fis |

eis8 fis4 eis8 fis[ \[ cis]^"S" fis4 ~ |

fis8 gis fis e dis e fis4 |

b, e ~ e8 dis cis4 | b \] e ~ e8 cisis dis4 }

\new Staff \relative c' { \clef alto \key dis \minor

cisis8[ \[ eis]^"S" ais4 ~ | ais8 b! ais gis fis gis ais4 |

dis, gis ~ gis8 fisis eis e |

dis \] b' ais gis fisis dis16 eis fis8 gis16 ais |

b4. ais8 gis fisis gis ais | dis, eis fisis gis ais16 b cis4 b16 ais

b4 r \[ gis2^"S (augmented)" | cis2. dis4 | cis b ais b |

cis2 fis, | b2. ais4 | gis2 fis4 \] b }

\new Staff \relative a, { \clef bass \key dis \minor

ais4 r | \[ ais'2^"S (augmented)" dis ~ | dis4 e dis cis |

b cis dis2 | gis, cis ~ | cis4 b ais2 \]

gis4^"S" cis ~ cis8 dis cis b | ais b cis4 fis, b ~ |

b8 ais gis4 fis8 e dis16 cis dis e |

ais,8 fis gis ais b cis dis e16 fis |

gis8 ais16 b cis,8 dis16 e fis,8 fis'4 fisis8 |

gis fisis gis ais b ais gis fis } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/o/qo05kutclut7tru7658nhmgu21uxec2/qo05kutc.png)

The student will find the subject and answer of the fugue in § 192. In our extract the subject in the middle voice is imitated in the fifth below and by augmentation, at half a bar's distance, therefore in a close stretto. On the completion of the subject by the alto, the treble gives it by inversion. Thus the augmented subject is accompanied in the first half by the subject in direct, and in the second half in inverted form. The bass then takes the subject in its direct form, and is followed (again at half a bar's distance) by the alto with the augmented subject. A comparison of the two voices here with their appearance at the beginning of our quotation shows us that the subject and its augmentation are here inverted in double counterpoint in the twelfth. The treble now accompanies the augmentation at a different point from before, and with the direct instead of the inverted form of the subject.

276. In speaking of the first stretto of Bach's fugue in E, in § 269, we said that Bach had other devices in reserve for the later part of the fugue. The following extract will show what was meant.

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 33.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\new Staff \relative g' { \key a \major \time 4/2 \partial 1

r2 \[ gis^"S (diminished)" | a4 cis b a gis2 \] ais |

b1 ~ b2. ais4 | b gis a b cis dis e2 ~ |

e2. dis4 e b2 ais4 | b2 r4 \[ fis'^"S (invd. & dimd.)" b, gis a b

cis2 b \] a gis | fis4 e' dis cis b2 s4 }

\new Staff \relative b { \clef alto \key a \major

bis4 cis2 bis4 | cis2 \[ dis^"S (dimd.)" e4 gis fis e |

dis \] a'! gis fis e gis fis e | dis e fis gis a2. gis4 |

fis e fis2 \[ e1^"S" | fis2 a! gis fis |

e4 \] a2 gis4 fis d' cis b | a fisis gis ais gis s2_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative e { \clef tenor \key a \major

e2 dis | e r r1 | r2 \[ b^"S (dimd.)" cis4 e dis cis |

b \] d cis b a2 b | b2. a4 gis2. \[ cis'4^"S (invd. & dimd.)" |

fis, dis e fis gis \] b cis dis |

gis,^"S (invd. & dimd.)" e fis gis a b cis2 ~ |

cis4 cis b ais b s2 }

\new Staff \relative g, { \clef bass \key a \major

gis1 ~ gis2 fis e4 cis fis2 | b r r \[ fis'^"S (dimd.)" |

gis4 b a gis fis2 \] e | b' \[ b,^"S (dimd.)" cis4 e dis cis |

dis \] b cis dis e2. \[ dis4^"S (invd. & dimd.)" |

e cis dis eis fis2. \] \[ eis4^"S (invd. & dimd.)" |

fis dis eis fisis \] gis2. } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/f/q/fqt3da306l3mp3dwos12oixx27w95t7/fqt3da30.png)

The first half of this passage shows us the subject treated by diminution, and imitated mostly at half a bar's distance. In the second half, the subject is both diminished and inverted, the first note being varied, and in this form it is used as a counterpoint against the subject in its original shape.

277. We said above (§ 252) that one voice was allowed to discontinue the subject in a stretto when the next voice entered with it. It is, however, sometimes possible for each voice to continue the subject to the end, so that the stretto is a canon at short distances of time for all the voices. A close stretto of this kind was called by the old theorists a stretto maestrale—that is, a "masterly stretto." The following is a fine example—

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 1.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\new Staff \relative c'' { \key c \major \time 4/4

c8. d32 c b8 \[ c^"S" d e f!8. g32 f |

e8 c d, g ~ g16 a g f e8 \] a |

d, bes' a g16 f g f g e f g g\prall f32 g | a16 s }

\new Staff \relative g' { \clef alto \key c \major

g8 fis gis a ~ a \[ g^"S" a b |

c8. d32 c b8 e a, d ~ d16 e d c | b8 \] g' cis, d e cis d e | a, }

\new Staff \relative c' { \clef tenor \key c \major

c8 a e'4 d8 r r4 | r8 \[ a^"S" b cis d8. e32 d c8 f |

b, e ~ e16 f e d cis8 \] r8 r4 | r8 }

\new Staff \relative a, { \clef bass \key c \major

a8 d ~ d16 e d c b8 bes a g | a fis' g e \[ d4^"S" e8 f |

g8. a32 g f8 bes e, a ~ a16 bes a g | f \] s } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/v/lvcgs9sm95gsumtb2f60kkwv16dr4fw/lvcgs9sm.png)

Here, though the interval of entry is irregular, there is a certain symmetry observable; the alto is a fourth below the treble, and the tenor a fifth above (the inversion of a fourth below) the bass. Such slight modifications of the subject as are seen in the tenor here are always permissible in a close stretto. The first notes of the bass are the conclusion of an entry of the subject in that voice.

278. Another interesting example of the stretto maestrale is seen in the following—

J. S. Bach. Wohltemperirtes Clavier, Fugue 29.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff \relative a' { \key d \major \time 4/4 \partial 2

a8 \[ a'^"S" a a | d,4 fis ~ fis8 b, e d | cis2 \] c ~ }

\new Staff \relative e' { \key d \major

e8 r r \[ fis' | fis fis b,4 d4. gis,8 | cis b a4 ~ \] a8 b fis e }

\new Staff \relative e { \clef tenor \key d \major

e8 r r4 | r8 \[ d' d d gis,4 b ~ | b8 e, a g fis4. \] a8 }

\new Staff \relative c { \clef bass \key d \major

cis8 a d cis | b r r \[ b' b b e,4 | g!4. cis,8 fis e d4 ~ \] } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/h/f/hfresfytpfwflqnut3jj9wwhyrmwuqn/hfresfyt.png)

Here the distances of entry are regular, both as regards time and interval, each voice entering a third (or tenth) below, and a crotchet after the preceding. The entries of alto and bass are consequently per arsin et thesin. Even a finer example may be seen in the fugue which forms the finale of Mozart's "Jupiter" symphony. The passage was quoted in Double Counterpoint, § 305, as an illustration of close imitation.

279. There is still one variety of stretto to be mentioned. Sometimes, though comparatively seldom, the first exposition of the fugue is in stretto, the answer entering before the completion of the subject, and very often immediately after its commencement. In such cases the second pair of voices will mostly follow the first pair with subject and answer at the same distance of interval and time.

J. S. Bach. Motett, "Der Geist hilft uns're Schwachheit auf."

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

\new Staff \relative b' { \key bes \major \time 2/2 \mark \markup \tiny { (\italic"a") }

R1*6 | r2 \[ bes2^"A" | f' f4 f | ees d ees c | d c d ees |

f c f2 ~ | f4 ees8 d ees4 c | d1 | c4 \] c f }

\new Staff \relative f' { \clef alto \key bes \major

R1*5 | r2 \[ f2^"S" bes bes4 bes | a g a f | g f g a |

bes f bes2 ~ | bes4 a8 g a4 f | g1 |

fis4 \] d g2 ~ | g4 f!8 e f4_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative b { \clef tenor \key bes \major

R1 | r2 \[ bes^"A" | f' f4 f | ees d ees c | d c d ees |

f c f2 ~ | f4 ees8 d ees4 bes | c1 | bes2 \] bes4 a | g d g2 |

f2. aes4 | d, c8 b c4 e | a, d8 c e4 bes | c bes c }

\new Staff \relative f { \clef tenor \key bes \major

r2 \[ f2^"S" bes bes4 bes | a g a f | g f g a | bes f bes2 ~ |

bes4 a8 g a4 f | g1 f2 \] d | g g ~ g4 a bes c |

d ees d c | b g c2 ~ | c4 bes!8 a bes4 g | a g a } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/8/y/8yy864qa8bujpk3w5qc1vq6hb219dzm/8yy864qa.png)

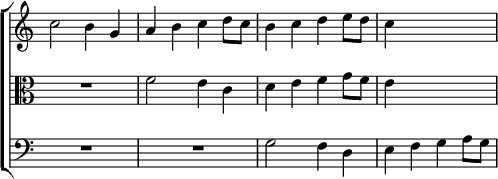

A fugue of this kind is generally called a "close fugue." We give two specimens of the beginning of a close fugue by other composers.

Handel. 'Israel in Egypt.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

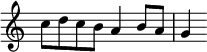

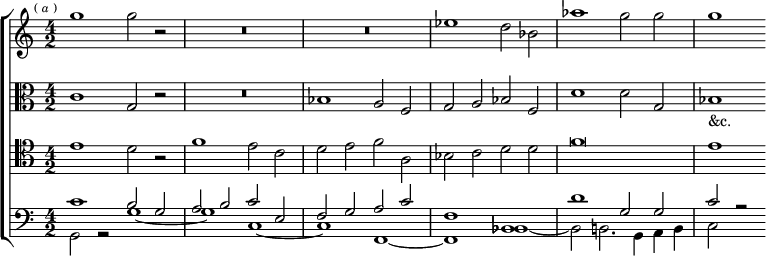

\new Staff \relative a' { \key a \minor \time 2/2 \mark \markup \tiny { (\italic"b") }

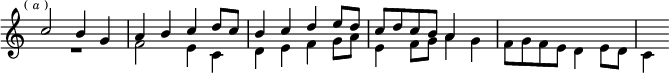

R1*5 \[ a1^"A" c b2 g a b c1 }

\new Staff \relative e' { \clef alto \key a \minor

R1*4 \[ d1^"S" f | e2 c | d e | f \] e4 d e1_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative a { \clef tenor \key a \minor

R1 \[ a1^"A" c b2 g | a b4 c \] | d a d2 | a1 g d' R }

\new Staff \relative d { \clef bass \key a \minor

\[ d1^"S" f e2 c d e f \] g d1 R1*3 r2 a' ~ } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/t/2t10zp7be6izp76upuosj9pf40rgwka/2t10zp7b.png)

Mendelssohn. 'St. Paul.'

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

\new Staff \relative a' { \time 3/2 \key d \minor \partial 1 \mark \markup \tiny { (\italic"c") }

r2 r | R1.*3 r2 \[ a^"A" bes | c1 c2 | c b cis | d1. a2 \] s }

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef alto \key d \minor

r2 r | R1.*2 r2 \[ d^"S" e | f1 f2 | f e f g1. d1 \] f2 e s_"&c." }

\new Staff \relative a { \clef tenor \key d \minor

r2 r | r \[ a^"A" bes | c1 c2 | c b cis | d1. |

a \] r2 r e' | a,1 b2 | cis s }

\new Staff \relative d { \clef bass \key d \minor

\[ d2^"S" e | f1 f2 | f e f | g1. d \] |

r2 r a' | g2. f4 e2 | f f g | a1 } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/e/a/eah2c7pi5clm1l8fh0u2jbsebi2r8hb/eah2c7pi.png)

280. The second pair of entries in a close fugue is sometimes at a different distance of time from the first.

Handel. 'Jubilate.'

Here the tenor follows the alto at one bar's distance; but the treble does not enter till three bars after the bass. Notice that here, as the first entries are by the middle voices, the second pair of entries give the inversion of the first pair—the answer being now above the subject instead of below it. If the student will examine the various entries of the subject here, he will see that they differ so much towards the close as to render it impossible to decide with absolute certainty where the subject ends. For this reason we have not marked its limits as in our other examples.

281. In speaking of the answer of a fugue, we pointed out that a subject in the key of the tonic must have an answer in the key of the dominant. But if this is done with a close fugue, we shall have the music in two keys at the same time. In this case, therefore, to keep a clear tonality, we do not put the answer in the key of the dominant, but simply transpose the subject a fourth or fifth without leaving the key. In example (a) of § 279, the answer is just as much in the key of B flat as the subject.

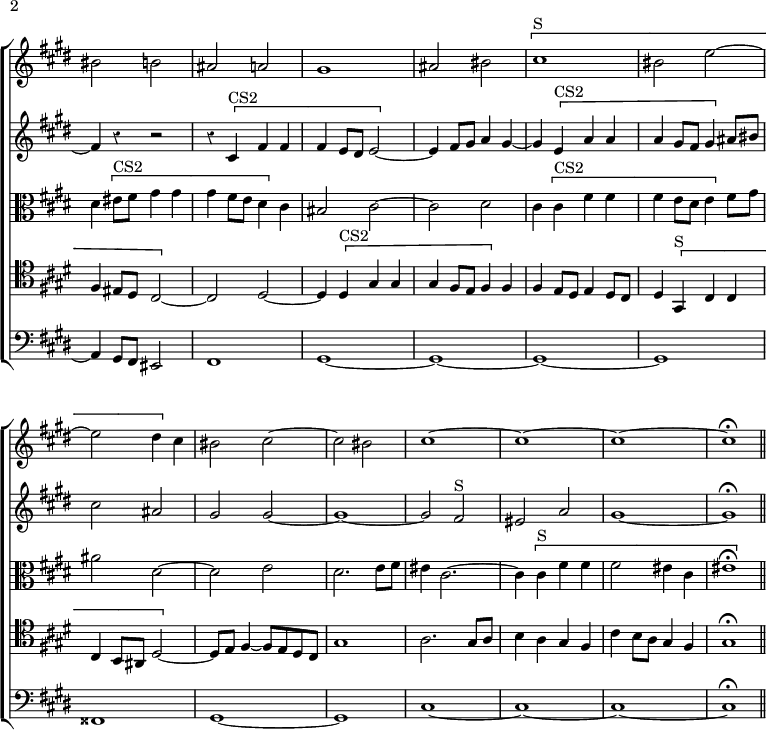

282. As all our examples till now have been from Bach and Handel, we will conclude this chapter with some extracts from the works of more modern composers. Next to Bach, the greatest master of all kinds of scientific writing is unquestionably Mozart. We saw this in the specimens of canon by him given in our last volume; and he is no less great in fugal writing. One of the best, though one of the least known, of his masses, is No. 12 in C. This work contains three fine fugues, in one of which, the "Et vitam," we meet with a peculiarity of form, deserving mention. A partial stretto occurs on the first entry of the answer, and this is seen against each succeeding entry. We quote the exposition.

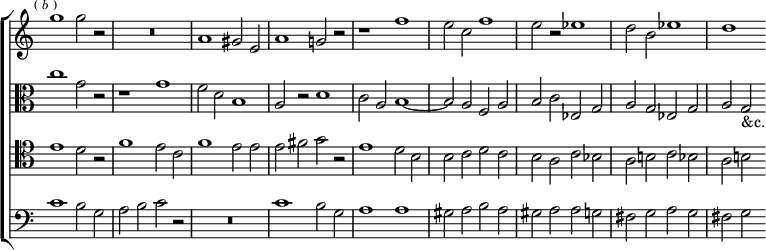

Mozart. Mass in C, No. 12.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff \relative c'' { \time 2/2 \key c \major

R1*15 | r2 \[ c^"A" | e d | r4 g, c c | c4. c8 b4 g8 a |

b4 a8 b c4 b8 c | d e d c b2 \] | R1 r2 g | d c }

\new Staff \relative g' { \clef alto \key c \major

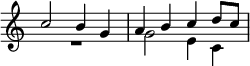

R1*10 | r2 \[ g^"S" | a g | r4 c, f f | f4. f8 e4 c8 d |

e4 d8 e f4 e8 f | g a g f e2 \] | r2 g | b a | r4 d, g g |

g4. g8 fis2 | R1 r4 \[ f!2^"CS" e4 | r c'2 b4 | b,2 c }

\new Staff \relative c' { \clef tenor \key c \major

R1*5 | r2 \[ c^"A" | e d | r4 g, c c | c4. c8 b4 g8 a |

b4 a8 b c4 b8 c | d e d c b2 \] | r2 c | e d | r4 g, c c |

c4. c8 b2 | R1 r4 \[ c2^"CS" b4 | r g'2 fis4 | fis,2 g ~ |

g a \] | R1 r2 c | e d | r4 g, c c^"etc." }

\new Staff \relative g { \clef bass \key c \major

r2 \[ g^"S" | a g | r4 c, f f | f4. f8 e4 c8 d |

e4 d8 e f4 e8 f | g a g f e2 \] | r2 g | b a | r4 d, g g |

g4. g8 fis2 | R1 | r4 \[ f!2^"CS" e4 | r4 c'2 b4 | b,2 c ~ |

c d \] | R1*5 | r2 \[ g2^"S" | a g | r4 c, f f | f4. f8 e4 c8 d } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/a/2a7173itfvtgfka3d37aaxqhd9t6lxk/2a7173it.png)

It will be seen that when the tenor has the answer, the bass imitates it in stretto. When the alto enters with the subject, the imitation is given to the tenor, and then for the first time appears the countersubject in the bass; it thus accompanies the second entry of the subject instead of the first entry of the answer as usual. There is an additional entry (§ 186) of the subject in the bass, to allow both the countersubject and the imitation in stretto to appear above it.

283. From the numerous stretti found in this fugue, we select two for quotation.

Mozart. Mass in C, No. 12.

Here not more than three of the voices are engaged with the subject at the same time. It will be seen that the entries in the bass and treble are per arsin et thesin, and that the last voice to enter (the tenor) gives the subject complete, the other entries being mostly fragmentary. Our second extract

is the last and closest stretto, and is founded only on the first part of the subject. In this all the voices take part.

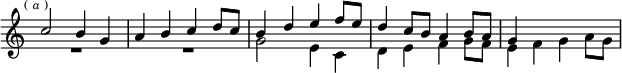

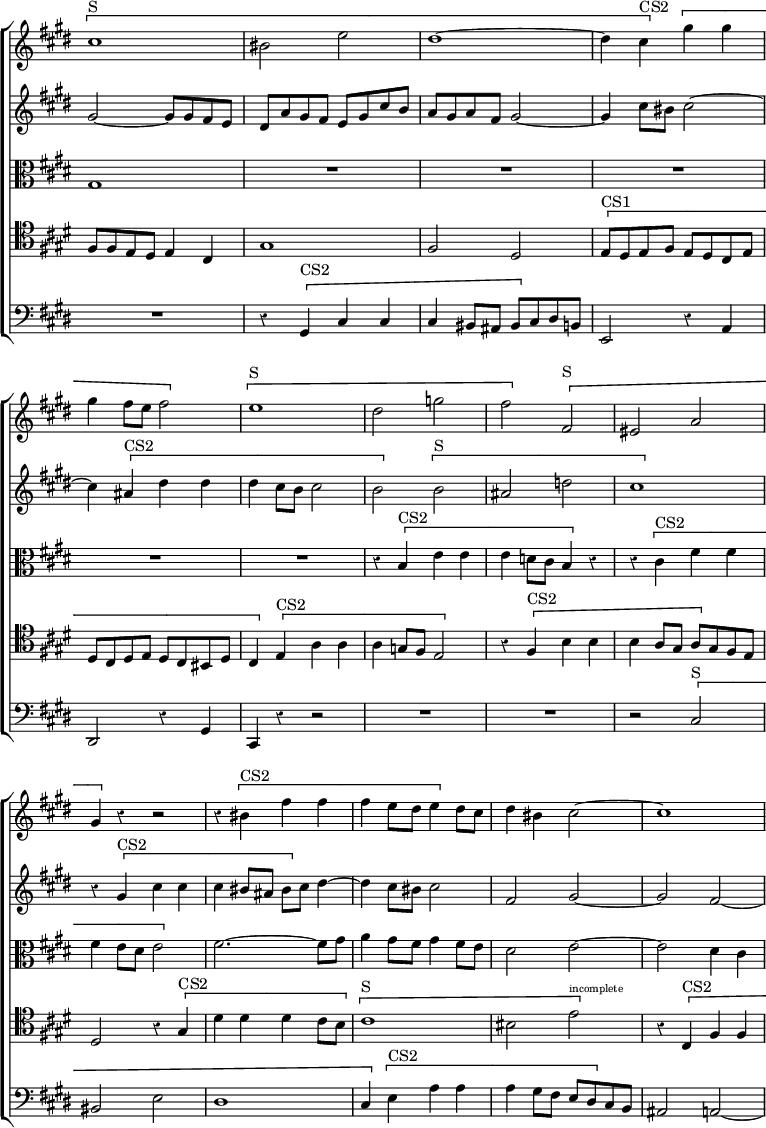

284. The fugue in Mozart's quartett in D minor (No. 13), of which we gave the subject in § 150, is particularly rich in good stretti. We give some of the closest.

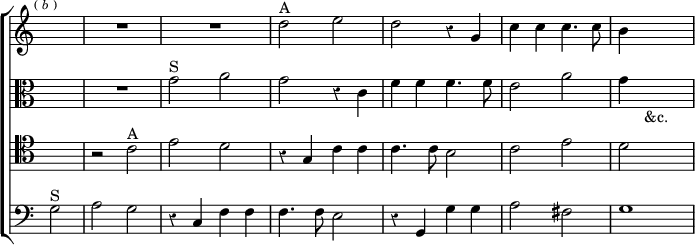

Mozart. Quartett in D minor, No. 13.

![#(set-global-staff-size 19)

\header { tagline = ##f }

\score { \new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.PageNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

\new Staff \with { instrumentName = \markup { \caps "Violino" 1mo. } } \relative d'' { \time 4/4 \partial 2 \key d \minor \mark \markup \tiny { (\italic"a") }

d2 | cis4 c b bes | a2 r | r a' | gis4 g fis f |

\partial 4. ees4. \bar "||" \mark \markup \tiny { (\italic"b") }

R1*3 %end prev page

R1 r2 a2 | fis4 f e ees | d4. d8 cis4 c | b bes a2 |

r8 a d cis16 d e4 e, | r2 a | gis4 g fis f | e4. e8 d4 r \bar "||"

\mark \markup \tiny { (\italic"c") }

d''2 cis4 c | b bes a4. a8 |b4 cis d4. d,8 | e4 fis g4. g8 |

g4 f! e d ~ | \partial 2. d cis d \bar "||"

\mark \markup \tiny { (\italic"d") } R1*2 %end this page

R1 d,2( cis4 c) | b( bes a) s \bar "||" }

\new Staff \with { instrumentName = \markup { \caps "Violino" 2do. } } \relative a { \key d \minor

a2 | r e'' | dis4 d cis c | b bes a d ~ | d cis d2 | b4. | R1*3

d,2 f4 fis | g gis a2 ~ | a bes | a g4 fis |

g4. f8 e a, a' g | f8. e16 d4 r2 | d2 cis4 c |

b a2 d4 ~ | d cis d r

r2 e' | dis4 d cis c | d e a,4. a8 | b4 a g d' |

cis d bes a | g8 a16 bes a8 a a4 | R1*2

d,2 cis4 c | b bes a2 | g4 d'2 s4 }

\new Staff \with { instrumentName = \markup \caps "Viola." } \relative a' { \clef alto \key d \minor

r2 | a gis4 g | fis f e2 ~ | e4 cis d a' | b a2 a4 | g4. |

R1 r2 a, | bes4 b c cis | %end prev page

d a4. d,8[ d' c] | b c16 d e8 d cis4 d8 e | d4 r g2 |

fis4 f e d ~ | d e8 d cis2 | r a | gis4 g2 fis4 | f e d a' |

bes a8 g f4 r | R1 r2 a' | gis4 g fis f | g ees d g | e d cis d |

e4. e8 d4 | R1 d2 cis4 c | %end this page

b bes a2 | g e4_( d) _~ d_( g fis) s }

\new Staff \with { instrumentName = \markup \caps "Violoncello" } \relative f, { \clef bass \key d \minor

f2 | R1 r2 a' | gis4 g fis f | e a d,4. d8 g4.^"&c." |

d2 cis4 c | b bes a fis' | g f! e a8 g | %end prev page

f8. e16 d4 r d | g e a8 a, b cis | d2 r R1*2 | d2 cis4 c |

b bes a dis | d! cis d d | g, a d, r | R1*2 r2 d''2 |

cis4 c b bes | a4. gis8 g4 f | e8 d16 g a8 g f a |

d,2 cis4 c b bes a2 | %end this page

g2.( fis4) | g2.( fis4) | g2 d } >>

\layout { indent = 2.0\cm } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/e/2/e26rfvlukeqnzz3vodb8bi1r2rt0qrw/e26rfvlu.png)

After the full explanations given of previous examples, but fewwords are needed with regard to these. Observe that at (b) both subject and answer are employed by inversion, as well as in their direct form; and that at (d) all the imitations are in the unison and octave.

285. It is not uncommon in a stretto to find the last notes of the subject slightly altered. In the fugue occurring in the course of the second chorus of Mendelssohn's 95th Psalm, we find a stretto so continuous that if the original subject

had been retained unaltered, we should have had a stretto maestrale. It will be seen that the modification is in the melody, not in the rhythm.

Mendelssohn. 95th Psalm.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff \relative g'' { \time 6/4 \key c \major

g2. c, | R1. | r2 r4 \[ f,4^"S" g f | bes2 d4 ~ d c b \] |

\[ a^"S" bes a d2 f4 ~ f e d cis4. d8 e4 \] |

e2. d2 d4 | d2. gis, }

\new Staff \relative c' { \clef alto \key c \major

r2 r4 \[ c^"S" d c | f2 a4 ~ a g f | e4. f8 g4 \] f e f ~ |

f e f g4. g8 g4 | g2. f4 g a | bes2 r4 \[ e,4 g e |

a2 c4 ~ c b a | gis2. b }

\new Staff \relative e' { \clef tenor \key c \major

e2. e | \[ f,4^"S" g f bes2 d4 ~ | d c bes a4. bes8 c4 \] |

d4 bes a g2 c4 | c2 cis4 d2. ~ d4 cis d g2 c,4 |

\[ a^"S" b! a d2 f4 \] | e2. e }

\new Staff \relative b { \clef bass \key c \major

bes1. | a2 r4*4/1 \[ c,4^"S" d c f2 a4 ~ | a g f e4. e8 e4 \] |

f2 e4 \[ d^"S" e d | g2 bes4 ~ bes a g |

fis2. \] f2 d4 | e2. e } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/i/e/ieoc9mvm8dcsb7440lkdwd9dzgd0lv4/ieoc9mvm.png)

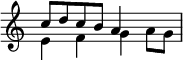

286. Our next illustration is by Spohr. The original subject of the fugue is

In the last and closest stretto of this fugue, only the first notes of the subject are imitated by the alto and tenor; but the treble, which enters last, gives the entire subject, though with some modifications of detail.

Spohr. 'Fall of Babylon.

287. Our last examples, by a living composer, will illustrate the modern freedom of treatment in a stretto.

Brahms. Deutches Requiem.

The lower notes on the bass staff are the real bass of the harmony, given to the orchestra; the upper notes show the voice part. Here is an example of a close stretto, modulating freely from C through F and B flat to E flat. This is distinctly modern in character; the old masters rarely go beyond tonic and dominant keys in a very close stretto.

In this passage from the same fugue, the imitation is closer and more continuous than in the preceding. There are in all nine entries of the fragment of the subject, the last being a sequential repetition of the preceding.

288. The stretto is capable, as will be seen from our examples, of so much variety that it is impossible to deal exhaustively with the subject in such a book as this. It is hoped that enough has been said in this chapter to enable the student to analyze for himself, and to understand any stretti that he may meet with in the fugues he may be playing. He will learn far more by such analysis than in any other way; and it is for this reason that we have dissected and explained so many passages in this and the preceding chapters.

289. As practical exercises on the stretto, let the student take the fugue subjects given at the end of Chapter IV., and try to make as many stretti as he can from them. He will find that some of them will work quite easily in this way, while others will be less pliable. He should try them at various distances, both of time and interval. For his two-part stretti he should also write free parts, making three or four-part harmony.