Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man/Chapter 8

CHAPTER VIII.

POST-PLIOCENE ALLUVIUM WITH FLINT IMPLEMENTS OF THE VALLEY OF THE SOMME,

Concluded.

FLUVIO-MARINE STRATA, WITH FLINT IMPLEMENTS, NEAR ABBEVILLE—MARINE SHELLS IN SAME—CYRENA FLUMINALIS—MAMMALIA—ENTIRE SKELETON OF RHINOCEROS—FLINT IMPLEMENTS, WHY FOUND LOW DOWN IN FLUVIATILE DEPOSITS—RIVERS SHIFTING THEIR CHANNELS—RELATIVE AGES OF HIGHER AND LOWER-LEVEL GRAVELS—SECTION OF ALLUVIUM OF ST. ACHEUL—TWO SPECIES OF ELEPHANT AND HIPPOPOTAMUS COEXISTING WITH MAN IN FRANCE—VOLUME OF DRIFT, PROVING ANTIQUITY OF FLINT IMPLEMENTS—ABSENCE OF HUMAN BONES IN TOOL-BEARING ALLUVIUM, HOW EXPLAINED—VALUE OF CERTAIN KINDS OF NEGATIVE EVIDENCE TESTED THEREBY—HUMAN BONES NOT FOUND IN DRAINED LAKE OF HAARLEM.

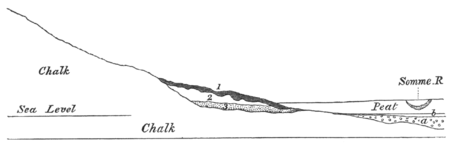

IN the section of the valley of the Somme, given at p. 106 (fig. 7), the successive formations newer than the chalk are numbered in chronological order, beginning with the most modern, or the peat, which is marked No. 1, and which has been treated of in the last chapter. Next in the order of antiquity are the lower-level gravels No. 2, which we have now to describe; after which the alluvium, No. 3, found at higher levels, or about eighty and one hundred feet above the river-plain, will remain to be considered.

I have selected, as illustrating the old alluvium of the Somme occurring at levels slightly elevated above the present river, the sand and gravel-pits of Menchecourt, in the northwest suburbs of Abbeville, to which, as before stated, p. 94, attention was first drawn by M. Boucher de Perthes, in his work on Celtic antiquities. Here, although in every adjoining pit some minor variations in the nature and thickness of the superimposed deposits may be seen, there is yet a general approach to uniformity in the series. The only stratum of which the relative age is somewhat doubtful, is the gravel marked a, underlying the peat, and resting on the chalk. It is only known by borings, and some of it may be of the same age as No. 3; but I believe it to be for the most part of more modern origin, consisting of the wreck of all the older gravel, including No. 3, and formed during the last hollowing out

Fig. 16

Section of fluvio-marine strata, containing flint implements and bones of extinct mammalia, at Menchecourt, Abbeville.[1]

2 Calcareous loam, buff-coloured, resembling loess, for the most part unstratified, in some places with slight traces of stratification, containing freshwater and land shells, with bones of elephants, &c.; thickness about fifteen feet.

3 Alternations of beds of gravel, marl, and sand, with freshwater and land shells, and in some of the lower sands, a mixture of marine shells; also bones of elephant, rhinoceros, &c., and flint implements; thickness about twelve feet.

a Gravel underlying peat, age undetermined.

b Layer of impervious clay, separating the gravel from the peat.and deepening of the valley immediately before the commencement of the growth of peat.

The greater number of flint implements have been dug out of No. 3, often near the bottom, and twenty-five, thirty, or even more than thirty feet below the surface of No. 1.

A geologist will perceive by a glance at the section that the valley of the Somme must have been excavated nearly to its present depth and width when the strata of No. 3 were thrown down, and that after the deposits Nos. 3, 2, and 1 had been formed in succession, the present valley was scooped out, patches only of Nos. 3 and 2 being left. For these deposits cannot originally have ended abruptly as they now do, but must have once been continuous farther towards the centre of the valley.

To begin with the oldest, No. 3, it is made up of a succession of beds, chiefly of freshwater origin, but occasionally a mixture of marine and fluviatile shells is observed in it, proving that the sea sometimes gained upon the river, whether at high tides or when the fresh water was less in quantity during the dry season, and sometimes perhaps when the land was slightly depressed in level. All these accidents might occur again and again at the mouth of any river, and give rise to alternations of fluviatile and marine strata, such as are seen at Menchecourt.

In the lowest beds of gravel and sand in contact with the chalk, flint hatchets, some perfect, others much rolled, have been found; and in a sandy bed in this position some workmen, whom I employed to sink a pit, found four flint knives. Above this sand and gravel occur beds of white and siliceous sand, containing shells of the genera Planorbis, Limnea, Paludina, Valvata, Cyclas, Cyrena, Helix, and others, all now natives of the same part of France, except Cyrena fluminalis (fig. 17), which no longer lives in Europe, but inhabits the Nile, and many parts of Asia, including Cashmere, where it abounds. No species of Cyrena is now met with in a living state in Europe. Mr. Prestwich first observed it fossil at Menchecourt, and it has since been found in two or three contiguous sand-pits, always in the fluvio-marine bed.

The following marine shells occur mixed with the freshwater species above enumerated:—Buccinum undatum, Littorina littorea, Nassa reticulata, Purpura lapillus, Tellina solidula, Cardium edule, and fragments of some others. Several of these I have myself collected entire, though in a state of great decomposition, lying in the white sand called 'sable aigre' by the workmen. They are all littoral species now proper to the contiguous coast of France. Their occurrence in a fossil state associated with freshwater shells at Menchecourt, had been noticed as long ago as 1836 by

Fig. 17

a Interior of left valve, from Gray's Thurrock, Essex.

b Hinge of same magnified.

c Interior of right valve of a small specimen, from Shacklewell, London.

d Outer surface of right valve, from Erith, Kent.

Dates of Specific Names

Cyrena fluminalis Müller |

1774 |

"Euphratis Chemnitz |

1782 |

"consobrina Gaillaud |

1823 |

"trigonula S. Wood |

1834 |

"gemmelarii Philippi |

1836 |

"Duchastelii Nyst |

1838 |

Corbicula fluminalis Mörsch |

1853 |

MM. Ravin and Baillon, before M. Boucher de Perthes commenced the researches which have since made the locality so celebrated.[2] The numbers since collected preclude all idea of their having been brought inland as eatable shells by the fabricators of the flint hatchets found at the bottom of the fluvio-marine sands. From the same beds, and in marls alternating with the sands, remains of the elephant, rhinoceros, and other mammalia, have been exhumed.

Above the fluvio-marine strata are those designated No. 2 in the section (fig. 16), which are almost devoid of stratification, and probably formed of mud or sediment thrown down by the waters of the river when they overflowed the ancient alluvial plain of that day. Some land shells, a few river shells, and bones of mammalia, some of them extinct, occur in No. 2. Its upper surface has been deeply furrowed and cut into by the action of water, at the time when the earthy matter of No. 1 was superimposed. The materials of this uppermost deposit are arranged as if they had been the result of land floods, taking place after the formations 2 and 3 had been raised, or had become exposed to denudation.

The fluvio-marine strata and overlying loam of Menchecourt recur on the opposite or left bank of the alluvial plain of the Somme, at a distance of two or three miles. They are found at Mautort, among other places, and I obtained there the flint hatchet figured at p. 115 (fig. 9), of an oval form. It was extracted from gravel, above which were strata containing a mixture of marine and freshwater shells, precisely like those of Menchecourt. In the alluvium of all parts of the valley, both at high and low levels, rolled bones are sometimes met with in the gravel. Some of the flint tools in the gravel of Abbeville have their angles very perfect, others have been much triturated, as if in the bed of the main river or some of its tributaries.

The mammalia most frequently cited as having been found in the deposits Nos. 2 and 3 at Menchecourt, are the following:—

Elephas primigenius.

Rhinoceros tichorhinus.

Equus fossilis Owen.

Bos primigenius.

Cervus somonensis Cuvier.

C. Tarandus priscus Cuvier.

Felis spelæa.

Hyæna spelæa.

The Ursus spelæus has also been mentioned by some writers; but M. Lartet says he has sought in vain for it among the osteological treasures sent from Abbeville to Cuvier at Paris, and in other collections. The same palæontologist, after a close scrutiny of the bones sent formerly to the Paris Museum from the valley of the Somme, observed that some of them bore the evident marks of an instrument, agreeing well with incisions such as a rude flint-saw would produce. Among other bones mentioned as having been thus artificially cut, are those of a Rhinoceros tichorhinus, and the antlers of Cervus somonensis.[3]

The evidence obtained by naturalists that some of the extinct mammalia of Menchecourt really lived and died in this part of France, at the time of the embedding of the flint tools in fluviatile strata, is most satisfactory; and not the less so for having been put on record long before any suspicion was entertained that works of art would ever be detected in the same beds. Thus M. Baillon, writing in 1834 to M. Ravin, says, 'They begin to meet with fossil bones at the depth of ten or twelve feet in the Menchecourt sand-pits, but they find a much greater quantity at the depth of eighteen and twenty feet. Some of them were evidently broken before they were embedded, others are rounded, having, without doubt, been rolled by running water. It is at the bottom of the sand-pits that the most entire bones occur. Here they lie without having undergone fracture or friction, and seem to have been articulated together at the time when they were covered up. I found in one place a whole hind limb of a rhinoceros, the bones of which were still in their usual relative position. They must have been joined together by ligaments, and even surrounded by muscles at the time of their interment. The entire skeleton of the same species was lying at a short distance from the spot.'[4]

If we suppose that the greater number of the flint implements occurring in the neighbourhood of Abbeville and Amiens were brought by river action into their present position, we can at once explain why so large a proportion of them are found at considerable depths from the surface, for they would naturally be buried in gravel and not in fine sediment, or what may be termed 'inundation mud,' such as No. 2 (fig. 16, p. 122), a deposit from tranquil water, or where the stream had not sufficient force or velocity to sweep along chalk flints, whether wrought or unwrought. Hence we have almost always to pass down through a mass of incumbent loam with land shells, or through fine sand with fresh water mollusks, before we get into the beds of gravel containing hatchets. Occasionally a weapon used as a projectile may have fallen into quiet water, or may have dropped from a canoe to the bottom of the river, or may have been floated by ice, as are some stones occasionally by the Thames in severe winters, and carried over the meadows bordering its banks; but such cases are exceptional, though helping to explain how isolated flint tools or pebbles and angular stones are now and then to be seen in the midst of the finest loams.

The endless variety in the sections of the alluvium of the valley of the Somme, may be ascribed to the frequent silting up of the main stream and its tributaries during different stages of the excavation of the valley, probably also during changes in the level of the land. As a rule, when a river attacks and undermines one bank, it throws down gravel and sand on the opposite side of its channel, which is growing shallower, and is soon destined to be raised so high as to form an addition to the alluvial plain, and to be only occasionally inundated. In this way, after much encroachment on cliff or meadow in one direction, we find at the end of centuries that the width of the channel has not been enlarged, for the new made ground is raised after a time to the full height of the older alluvial tract. Sometimes an island is formed in midstream, the current flowing for a while on both sides of it, and at length scooping out a deeper channel on one side so as to leave the other to be gradually filled up during freshets and afterwards elevated by inundation mud, or 'brick-earth.' During the levelling up of these old channels, a flood some times cuts into and partially removes portions of the previously stratified matter, causing those repeated signs of furrowing and filling up of cavities, those memorials of doing and undoing, of which the tool-bearing sands and gravels of Abbeville and Amiens afford such reiterated illustrations, and of which a parallel is furnished by the ancient alluvium of the Thames valley, where similar bones of extinct mammalia and shells, including Cyrena fluminalis, are found.

Professor Noeggerath, of Bonn, informs me that, about the year 1845, when the bed of the Rhine was deepened artificially by the blasting and removal of rock in the narrows at Bingerloch, not far from Bingen, several flint hatchets and an extraordinary number of iron weapons of the Roman period were brought up by the dredge from the bed of the great river. The decomposition of the iron had caused much of the gravel to be cemented together into a conglomerate. In such a case we have only to suppose the Rhine to deviate slightly from its course, changing its position, as it has often done in various parts of its plain in historical times, and then tools of the stone and iron periods would be found in gravel at the bottom, with a great thickness of sand and overlying loam deposited above them.

Changes in a river plain, such as those above alluded to, give rise frequently to ponds, swamps, and marshes, marking the course of old beds or branches of the river not yet filled up, and in these depressions shells proper both to running and stagnant water may be preserved, and quadrupeds may be mired. The latest and uppermost deposit of the series will be loam or brick-earth, with land and amphibious shells (Helix and Succinea), while below will follow strata containing freshwater shells, implying continuous submergence; and lowest of all in most sections will be the coarse gravel accumulated by a current of considerable strength and velocity.

When the St. Katharine docks were excavated at London, and similar works executed on the banks of the Mersey, old ships were dug out, as I have elsewhere noticed,[5] showing how the Thames and Mersey have in modern times been shifting their channels. Recently, an old silted-up bed of the Thames has been discovered by boring at Shoeburyness at the mouth of the river opposite Sheerness, as I learn from Mr. Milne. The old deserted branch is separated from the new or present channel of the Thames, by a tertiary outlier composed of London clay. The depth of the old branch, or the thickness of fluviatile strata with which it has been filled up, is seventy-five feet. The actual channel in the neighbourhood is now sixty feet deep, but there is probably ten or fifteen feet of stratified sand and gravel at the bottom; so that, should the river deviate again from its course, its present bed might be the receptacle of a fluvio-marine formation seventy-five feet thick, equal to the former one of Shoeburyness, and more considerable than that of Abbeville. It would consist both of freshwater and marine strata, as the salt water is carried by the tide far up above Sheerness; but in order that such deposits should resemble, in geological position, the Menchecourt beds, they must be raised ten or fifteen feet above their present level, and be partially eroded. Such erosion they would not fail to suffer during the process of upheaval, because the Thames would scour out its bed, and not alter its position relatively to the sea, while the land was gradually rising.

Before the canal was made at Abbeville, the tide was perceptible in the Somme for some distance above that city. It would only require, therefore, a slight subsidence to allow the saltwater to reach Menchecourt, as it did in the post-pliocene period. As a stratum containing exclusively land and freshwater shells usually underlies the fluvio-marine sands at Menchecourt, it seems that the river first prevailed there, after which the land subsided; and then there was an upheaval which raised the country to a greater height than that at which it now stands, after which there was a second sinking, indicated by the position of the peat, as already explained (p. 111). All these changes happened since man first inhabited this region.

At several places in the environs of Abbeville there are fluviatile deposits at a higher level by fifty feet than those of Menchecourt, resting in like manner on the chalk. One of these occurs in the suburbs of the city at Moulin Quignon, one hundred feet above the Somme and on the same side of the valley as Menchecourt, and containing flint implements of the same antique type and the bones of elephants; but no marine shells have been found there, nor in any gravel or sand at higher elevations than the Menchecourt marine shells.

It has been a matter of discussion among geologists whether the higher or the lower sands and gravels of the Somme valley are the more ancient. As a general rule, when there are alluvial formations of different ages in the same valley, those which occupy a more elevated position above the river plain are the oldest. In Auvergne and Velay, in Central France, where the bones of fossil quadrupeds occur at all heights above the present rivers from ten to one thousand feet, we observe the terrestrial fauna to depart in character from that now living in proportion as we ascend to higher terraces and platforms. We pass from the lower alluvium, containing the mammoth, tichorhine rhinoceros, and reindeer, to various older groups of fossils, till, on a table-land a thousand feet high (near Le Puy, for example), the abrupt termination of which overlooks the present valley, we discover an old extinct river-bed covered by a current of ancient lava, showing where the lowest level was once situated. In that elevated alluvium the remains of a tertiary mastodon and other quadrupeds of like antiquity are embedded.

If the Menchecourt beds had been first formed, and the valley, after being nearly as deep and wide as it is now, had subsided, the sea must have advanced inland, causing small delta-like accumulations at successive heights, wherever the main river and its tributaries met the sea. Such a movement, especially if it were intermittent, and interrupted occasionally by long pauses, would very well account for the accumulation of stratified debris which we encounter at certain points in the valley, especially around Abbeville and Amiens. But we are precluded from adopting this theory by the entire absence of marine shells, and the presence of fresh-water and land species, and mammalian bones, in considerable abundance, in the drift both of higher and lower levels above Abbeville. Had there been a total absence of all organic remains, we might have imagined the former presence of the sea, and the destruction of such remains might have been ascribed to carbonic acid or other decomposing causes; but the post-pliocene and implement-bearing strata can be shown by their fossils to be of fluviatile origin.

Flint Implements in Gravel near Amiens.

Gravel of St. Acheul.

When we ascend the valley of the Somme, from Abbeville to Amiens, a distance of about twenty-five miles, we observe a repetition of all the same alluvial phenomena which we have seen exhibited at Menchecourt and its neighbourhood, with the single exception of the absence of marine shells and of Cyrena fluminalis. We find lower-level gravel, such as No. 2, fig. 7, p. 106, and higher-level alluvium, such as No. 3, the latter rising to one hundred feet above the plain, which at Amiens is about fifty feet above the level of the river at Abbeville. In both the upper and lower gravels, as Dr. Rigollot stated in 1854, flint tools and the bones of extinct animals, together with river shells and land shells of living species, abound.

Immediately below Amiens, a great mass of stratified gravel, slightly elevated above the alluvial plain of the Somme, is seen at St. Roch, and half a mile farther down the valley at Montiers. Between these two places, a small tributary stream, called the Celle, joins the Somme. In the gravel at Montiers, Mr. Prestwich and I found some flint knives, one of them flat on one side, but the other carefully worked, and exhibiting many fractures, clearly produced by blows skilfully applied. Some of these knives were taken from so low a level as to satisfy us that this great bed of gravel at Montiers, as well as that of the contiguous quarries of St. Roch, which seems to be a continuation of the same deposit, may be referred to the human period. Dr. Rigollot had already mentioned flint hatchets as obtained by him from St. Roch, but as none have been found there of late years, his statement was thought to require confirmation. The discovery, therefore, of these flint knives in gravel of the same age was interesting, Fig. 18

Elephas primigenius.

Penultimate molar, lower jaw, right side, one-third of natural size, Post-pliocene. Coexisted with man.

Fig. 19

Elephas antiquus Falconer.

Penultimate molar, lower jaw, right side, size one-third of nature, Post-pliocene and Newer pliocene. Coexisted with man.

Fig. 20[6]

Elephas meridionalis Nesti.

The alluvial formations of Montiers are very instructive in another point of view. If, leaving the lower gravel of that place, which is topped with loam or brick-earth (of which the upper portion is about thirty feet above the level of the Somme), we ascend the chalky slope to the height of about eighty feet, another deposit of gravel and sand, with fluviatile shells in a perfect condition, occurs, indicating most clearly an ancient river-bed, the waters of which ran habitually at that higher level before the valley had been scooped out to its present depth. This superior deposit is on the same side of the Somme, and about as high, as the lowest part of the celebrated formation of St. Acheul, two or three miles distant, to which I shall now allude.

The terrace of St. Acheul may be described as a gently sloping ledge of chalk, covered with gravel, topped as usual with loam or fine sediment, the surface of the loam being 100 feet above the Somme, and about 150 above the sea.

Many stone coffins of the Gallo-Roman period have been dug out of the upper portion of this alluvial mass. The trenches made for burying them sometimes penetrate to the depth of eight or nine feet from the surface, entering the upper part of No. 3 of the sections Nos. 21 and 21 a. They prove that when the Romans were in Gaul they found this terrace in the same condition as it is now, or rather as it was before the removal of so much gravel, sand, clay, and loam, for repairing roads, and for making bricks and pottery.

In the annexed section, which I observed during my last visit in 1860, it will be seen that a fragment of an elephant's tooth is noticed as having been dug out of unstratified sandy loam at the point a, eleven feet from the surface. This was found at the time of my visit; and at a lower point, at b, eighteen

Fig. 21

Section of a gravel pit containing flint implements at St. Acheul, near Amiens, observed in July 1860.

2 Brown loam with some angular flints, in parts passing into ochreous gravel, filling up indentations on the surface of No. 3,—three feet thick.

3 White siliceous sand with layers of chalky marl, and included fragments of chalk, for the most part unstratified,—nine feet.

4 Flint-gravel, and whitish chalky sand, flints subangular, average size of fragments, three inches diameter, but with some large unbroken chalk flints intermixed, cross stratification in parts. Bones of mammalia, grinder of elephant at b, and flint implement at c,—ten to fourteen feet.

5 Chalk with flints.

a Part of elephant's molar, eleven feet from the surface.

b Entire molar of E. primigenius, seventeen feet from surface.

c Position of flint hatchet, eighteen feet from surface.feet from the surface, a large nearly entire and unrolled molar of the same species was obtained, which is now in my possession. It has been pronounced by Dr. Falconer to belong to Elephas primigenius.

A stone hatchet of an oval form, like that represented at fig. 9, p. 115, was discovered at the same time, about one foot lower down, at c, in densely compressed gravel. The surface of the fundamental chalk is uneven in this pit, and slopes towards the valley-plain of the Somme. In a horizontal distance of twenty feet, I found a difference in vertical height of seven feet. In the chalky sand, sometimes occurring in interstices between the separate fragments of flint, constituting the coarse gravel No. 4, entire as well as broken fresh-water shells are often met with. To some it may appear enigmatical how such fragile objects could have escaped annihilation in a river-bed, when flint tools and much gravel were shoved along the bottom; but I have seen the dredging instrument employed in the Thames, above and below London Bridge, to deepen the river, and worked by steam power, scoop up gravel and sand from the bottom, and then pour the contents pell-mell into the boat, and still many specimens of Limnea, Planorbis, Paludina, Cyclas, and other shells might be taken out uninjured from the gravel.

It will be observed that the gravel No. 4 is obliquely stratified, and that its surface had undergone denudation before the white sandy loam, No. 3, was superimposed. The materials of the gravel at d must have been cemented or frozen together into a somewhat coherent mass to allow the projecting ridge, d, to stand up five feet above the general surface, the sides being in some places perpendicular. In No. 3 we probably behold an example of a passage from river-silt to inundation mud, or loess. In some parts of it, land shells occur.

It has been ascertained by MM. Buteux, Ravin, and other observers conversant with the geology of this part of France, that in none of the alluvial deposits, ancient or modern, are there any fragments of rocks foreign to the basin of the Somme—no erratics which could only be explained by supposing them to have been brought by ice, during a general submergence of the country, from some other hydrographical basin.

But in some of the pits at St. Acheul there are seen in the beds No. 4, fig. 21, not only well-rounded tertiary pebbles, but great blocks of hard sandstone, of the kind called in the south of England 'greyweathers,' some of which are three or four feet and upwards in diameter. They are usually angular, and when spherical owe their shape generally to an original concretionary structure, and not to trituration in a river's bed. These large fragments of stone abound both in the higher and lower level gravels round Amiens and at the higher level at Abbeville. They have also been traced far up the valley above Amiens, wherever patches of the old alluvium occur. They have all been derived from the tertiary strata which once covered the chalk. Their dimensions are such that it is impossible to imagine a river like the present Somme, flowing through a flat country, with a gentle fall towards the sea, to have carried them for miles down its channel, unless ice cooperated as a transporting power. Their angularity also favours the supposition of their having been floated by ice, or rendered so buoyant by it as to have escaped much of the wear and tear which blocks propelled along the bottom of a river channel would otherwise suffer. We must remember that the present mildness of the winters in Picardy and the north-west of Europe generally is exceptional in the northern hemisphere, and that large fragments of granite, sandstone, and limestone are now carried annually by ice down the Canadian rivers in latitudes farther south than Paris.[7]

Another sign of ice agency observed by me in many pits at St. Acheul, and of which Mr. Prestwich has given a good illustration in one of his published sections, deserves notice. It consists in flexures and contortions of the strata of sand,

Fig. 21 a

Contorted fluviatile strata at St. Acheul (Prestwich, Phil. Trans. 1861, p. 299).

2 Brown loam as in fig. 21, p. 135,—thickness, six feet.

3 White sand with bent and folded layers of marl—thickness, six feet.

4 Gravel, as in fig. 21, p. 135 with bones of mammalia and flint implements.

5 Chalk with flints.

a Graves filled with made ground and human bones.

b and c Seams of laminated marl often bent round upon themselves.

d Beds of gravel with sharp curves.marl, and gravel (as seen at b, c and d, fig. 21 a), which they have evidently undergone since their original deposition, and from which both the underlying chalk and part of the overlying beds of sand No. 3 are usually exempt.

In my former writings I have attributed this kind of derangement to two causes; first, the pressure of ice running aground on yielding banks of mud and sand; and, secondly, the melting of masses of ice and snow of unequal thickness, on which horizontal layers of mud, sand, and other fine and coarse materials had accumulated. The late Mr. Trimmer first pointed out in what manner the unequal failure of support caused by the liquefaction of underlying or intercalated snow and ice might give rise to such complicated foldings.[8]

When 'ice-jams' occur on the St. Lawrence and other Canadian rivers (lat. 46º N.), the sheets of ice, which become packed or forced under or over one another, assume in most cases a highly inclined and sometimes even a vertical position. They are often observed to be coated on one side with mud, sand, or gravel frozen on to them, derived from shallows in the river on which they rested when congelation first reached the bottom.

As often as portions of these packs melt near the margin of the river, the layers of mud, sand, and gravel, which result from their liquefaction, cannot fail to assume a very abnormal arrangement,—very perplexing to a geologist who should undertake to interpret them without having the ice-clue in his mind.

Mr. Prestwich has suggested that ground-ice may have had its influence in modifying the ancient alluvium of the Somme.[9] It is certain that ice in this form plays an active part every winter in giving motion to stones and gravel in the beds of rivers in European Russia and Siberia. It appears that when in those countries the streams are reduced nearly to the freezing point, congelation begins frequently at the bottom; the reason being, according to Arago, that the current is slowest there, and the gravel and large stones, having parted with much of their heat by radiation, acquire a temperature below the average of the main body of the river. It is, therefore, when the water is clear, and the sky free from clouds, that ground ice forms most readily, and oftener on pebbly than on muddy bottoms. Fragments of such ice, rising occasionally to the surface, bring up with them gravel, and even large stones.

Without dwelling longer on the various ways in which ice may affect the forms of stratification in drift, so as to cause bendings and foldings in which the underlying or overlying strata do not participate, a subject to which I shall have occasion again to allude in the sequel, I will state in this place that such contortions, whether explicable or not, are very characteristic of glacial formations. They have also no necessary connection with the transportation of large blocks of stone, and they therefore afford, as Mr. Prestwich remarks, independent proof of ice-action in the post-pliocene gravel of the Somme.

Let us, then, suppose that, at the time when flint hatchets were embedded in great numbers in the ancient gravel which now forms the terrace of St. Acheul, the main river and its tributaries were annually frozen over for several months in winter. In that case, the primitive people may, as Mr. Prestwich hints, have resembled in their mode of life those American Indians who now inhabit the country between Hudson's Bay and the Polar Sea. The habits of those Indians have been well described by Hearne, who spent some years among them. As often as deer and other game become scarce on the land, they betake themselves to fishing in the rivers; and for this purpose, and also to obtain water for drinking, they are in the constant practice of cutting round holes in the ice, a foot or more in diameter, through which they throw baited hooks or nets. Often they pitch their tent on the ice, and then cut such holes through it, using ice-chisels of metal when they can get copper or iron, but when not, employing tools of flint or hornstone.

The great accumulation of gravel at St. Acheul has taken place in part of the valley where the tributary streams, the Noye and the Arve, now join the Somme. These tributaries, as well as the main river, must have been running at the height first of a hundred feet, and afterwards at various lower levels above the present valley-plain, in those earlier times when the flint tools of the antique type were buried in successive river beds. I have said at various levels, because there are, here and there, patches of drift at heights intermediate between the higher and lower gravel, and also some deposits, showing that the river once flowed at elevations above as well as below the level of the platform of St. Acheul. As yet, however, no patch of gravel skirting the valley at heights exceeding one hundred feet above the Somme have yielded flint tools or other signs of the former sojourn of man in this region.

Possibly, in the earlier geographical condition of this country, the confluence of tributaries with the Somme afforded inducements to a hunting and fishing tribe to settle there, and some of the same natural advantages may have caused the first inhabitants of Amiens and Abbeville to fix on the same sites for their dwellings. If the early hunting and fishing tribes frequented the same spots for hundreds or thousands of years in succession, the number of the stone implements lost in the bed of the river need not surprise us. Ice-chisels, flint hatchets, and spear-heads may have slipped accidentally through holes kept constantly open, and the recovery of a lost treasure once sunk in the bed of the icebound stream, inevitably swept away with gravel on the breaking up of the ice in the spring, would be hopeless. During a long winter, in a country affording abundance of flint, the manufacture of tools would be continually in progress; and, if so, thousands of chips and flakes would be purposely thrown into the ice-hole, besides a great number of implements having flaws, or rejected as too unskilfully made to be worth preserving.

As to the fossil fauna of the drift, considered in relation to the climate, when I took a collection which I had made of all the more common species of land and freshwater shells from the Amiens and Abbeville drift, to my friend M. Deshayes at Paris, he declared them to be, without exception, the same as those now living in the basin of the Seine. This fact may seem at first sight to imply that the climate had not altered since the flint tools were fabricated; but it appears that all these species of mollusks now range as far north as Norway and Finland, and may therefore have flourished in the valley of the Somme when the river was frozen over annually in winter.

In regard to the accompanying mammalia, some of them, like the mammoth and tichorhine rhinoceros, may have been able to endure the rigours of a northern winter as well as the rein-deer, which we find fossil in the same gravel, it is a more difficult point to determine whether the climate of the lower gravels (those of Menchecourt, for example) was more genial than that of the higher ones. Mr. Prestwich inclines to this opinion. None of those contortions of the strata above described (p. 138) have as yet been observed in the lower drift. It contains large blocks of tertiary sandstone and grit, which may have required the aid of ice to convey them to their present sites; but as such blocks already abounded in the older and higher alluvium, they may simply be monuments of its destruction, having been let down successively to lower and lower levels without making much seaward progress.

The Cyrena fluminalis of Menchecourt and the hippopotamus of St. Roch seem to be in favour of a less severe temperature in winter; but so many of the species of mammalia, as well as of the land and fresh-water shells, are common to both formations, and our information respecting the entire fauna is still so imperfect, that it would be premature to pretend to settle this question in the present state of our knowledge. We must be content with the conclusion (and it is one of no small interest), that when man first inhabited this part of Europe, at the time that the St. Acheul drift was formed, the climate as well as the physical geography of the country differed considerably from the state of things now established there.

Among the elephant remains from St. Acheul, in M. Garnier's collection, Dr. Falconer recognised a molar of the Elephas antiquus, fig. 19, the same species which has been already mentioned as having been found in the lower-level gravels of St. Roch. This species, therefore, endured while important changes took place in the geographical condition of the valley of the Somme. Assuming the lower-level gravel to be the newer, it follows that the Elephas antiquus and the hippopotamus of St. Roch continued to flourish long after the introduction of the mammoth, a well characterized tooth of which, as I before stated, was found at St. Acheul at the time of my visit in 1860.

As flint hatchets and knives have been discovered in the alluvial deposits both at high and low levels, we may safely affirm that man was as old an inhabitant of this region as were any of the fossil quadrupeds above enumerated, a conclusion which is independent of any difference of opinion as to the relative age of the higher and lower gravels.

The disappearance of many large pachyderms and beasts of prey from Europe has often been attributed to the intervention of man, and no doubt he played his part in hastening the era of their extinction; but there is good reason for suspecting that other causes cooperated to the same end. No naturalist would for a moment suppose that the extermination of the Cyrena fluminalis throughout the whole of Europe—a species which coexisted with our race in the valley of the Somme, and which was very abundant in the waters of the Thames at the time when the elephant, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus flourished on its banks—was accelerated by human agency. The same modification in climate and other conditions of existence which affected this aquatic mollusk, may have mainly contributed to the gradual dying out of many of the large mammalia.

We have already seen that the peat of the valley of the Somme is a formation which, in all likelihood, took thousands of years for its growth. But no change of a marked character has occurred in the mammalian fauna since it began to accumulate. The contrast of the fauna of the ancient alluvium, whether at high or low levels, with the fauna of the oldest peat is almost as great as its contrast with the existing fauna, the memorials of man being common to the whole series; hence we may infer that the interval of time which separated the era of the large extinct mammalia from that of the earliest peat, was of far longer duration than that of the entire growth of the peat. Yet we by no means need the evidence of the ancient fossil fauna to establish the antiquity of man in this part of France. The mere volume of the drift at various heights would alone suffice to demonstrate a vast lapse of time during which such heaps of shingle, derived both from the Eocene and the cretaceous rocks, were thrown down in a succession of river-channels. We observe thousands of rounded and half-rounded flints, and a vast number of angular ones, with rounded pieces of white chalk of various sizes, testifying to a prodigious amount of mechanical action, accompanying the repeated widening and deepening of the valley, before it became the receptacle of peat; and the position of many of the flint tools leaves no doubt on the mind of the geologist that their fabrication preceded all this reiterated denudation.

On the Absence of Human Bones in the Alluvium of the Somme.

It is naturally a matter of no small surprise that, after we have collected many hundred flint implements (including knives, many thousands), not a single human bone has yet been met with in the alluvial sand and gravel of the Somme. This dearth of the mortal remains of our species holds true equally, as yet, in all other parts of Europe where the tool-bearing drift of the post-Pliocene period has been investigated in valley deposits. Yet in these same formations there is no want of bones of mammalia belonging to extinct and living species. In the course of the last quarter of a century, thousands of them have been submitted to the examination of skilful osteologists, and they have been unable to detect among them one fragment of a human skeleton, not even a tooth. Yet Cuvier pointed out long ago, that the bones of man found buried in ancient battle-fields were not more decayed than those of horses interred in the same graves. We have seen that in the Liége caverns, the skulls, jaws, and teeth, with other bones of the human race, were preserved in the same condition as those of the cave-bear, tiger, and mammoth.

That ere long, now that curiosity has been so much excited on this subject, some human remains will be detected in the older alluvium of European valleys, I confidently expect. In the mean time, the absence of all vestige of the bones which belonged to that population by which so many weapons were designed and executed, affords a most striking and instructive lesson in regard to the value of negative evidence, when adduced in proof of the non-existence of certain classes of terrestrial animals at given periods of the past. It is a new and emphatic illustration of the extreme imperfection of the geological record, of which even they who are constantly working in the field cannot easily form a just conception.

We must not forget that Dr. Schmerling, after finding extinct mammalia and flint tools in forty-two Belgian caverns, was only rewarded by the discovery of human bones in three or four of those rich repositories of osseous remains. In like manner, it was not till the year 1855 that the first skull of the musk buffalo (Bubalus moschatus) was detected in the fossiliferous gravel of the Thames, and not till 1860, as will be seen in the next chapter, that the same quadruped was proved to have co-existed in France with the mammoth. The same theory which will explain the comparative rarity of such species would no doubt account for the still greater scarcity of human bones, as well as for our general ignorance of the post-pliocene terrestrial fauna, with the exception of that part of it which is revealed to us by cavern researches.

In valley drift we meet commonly with the bones of quadrupeds which graze on plains bordering rivers. Carnivorous beasts, attracted to the same ground in search of their prey, sometimes leave their remains in the same deposits, but more rarely. The whole assemblage of fossil quadrupeds at present obtained from the alluvium of Picardy is obviously a mere fraction of the entire fauna which flourished contemporaneously with the primitive people by whom the flint hatchets were made.

Instead of its being part of the plan of nature to store up enduring records of a large number of the individual plants and animals which have lived on the surface, it seems to be her chief care to provide the means of disencumbering the habitable areas lying above and below the waters of those myriads of solid skeletons of animals, and those massive trunks of trees, which would otherwise soon choke up every river, and fill every valley. To prevent this inconvenience she employs the heat and moisture of the sun and atmosphere, the dissolving power of carbonic and other acids, the grinding teeth and gastric juices of quadrupeds, birds, reptiles, and fish, and the agency of many of the invertebrata. We are all familiar with the efficacy of these and other causes on the land; and as to the bottoms of seas, we have only to read the published reports of Mr. MacAndrew, the late Edward Forbes, and other experienced dredgers, who, while they failed utterly in drawing up from the deep a single human bone, declared that they scarcely ever met with a work of art even after counting tens of thousands of shells and zoophytes, collected on a coast line of several hundred miles in extent, where they often approached within less than half a mile of a land peopled by millions of human beings.

Lake of Haarlem.

It is not many years since the Government of Holland resolved to lay dry that great sheet of water formerly called the Lake of Haarlem, extending over 45,000 square acres. They succeeded, in 1853, in turning it into dry land, by means of powerful pumps constantly worked by steam, which raised the water and discharged it into a canal running for twenty or thirty miles round the newly-gained land. This land was depressed thirteen feet beneath the mean level of the ocean. I travelled, in 1859, over part of the bed of this old lake, and found it already converted into arable land, and peopled by an agricultural population of 5000 souls. Mr. Staring, who had been for some years employed by the Dutch Government in constructing a geological map of Holland, was my companion and guide. He informed me that he and his associates had searched in vain for human bones in the deposits which had constituted for three centuries the bed of the great lake.

There had been many a shipwreck, and many a naval fight in those waters, and hundreds of Dutch and Spanish soldiers and sailors had met there with a watery grave. The population which lived on the borders of this ancient sheet of water numbered between thirty and forty thousand souls. In digging the great canal, a fine section had been laid open, about thirty miles long, of the deposits which formed the ancient bottom of the lake. Trenches, also, innumerable, several feet deep, had been freshly dug on all the farms, and their united length must have amounted to thousands of miles. In some of the sandy soil recently thrown out of the trenches, I observed specimens of fresh-water and brackish-water shells, such as Unio and Dreissena, of living species; and in clay brought up from below the sand, shells of Tellina, Lutraria, and Cardium, all of species now inhabiting the adjoining sea.

One or two wrecked Spanish vessels, and arms of the same period, have rewarded the antiquaries who had been watching the draining operations in the hope of a richer harvest, and who were not a little disappointed at the result. In a peaty tract on the margin of one part of the lake a few coins were dug up; but if history had been silent, and if there had been a controversy whether man was already a denizen of this planet at the time when the area of the Haarlem lake was under water, the archæologist, in order to answer this question, must have appealed, as in the case of the valley of the Somme, not to fossil bones, but to works of art embedded in the superficial strata.

Mr. Staring, in his valuable memoir on the 'Geological Map of Holland,' has attributed the general scarcity of human bones in Dutch peat, notwithstanding the many works of art preserved in it, to the power of the humic and sulphuric acids to dissolve bones, the peat in question being plentifully impregnated with such acids. His theory may be correct, but it is not applicable to the gravel of the Valley of the Somme, in which the bones of fossil mammalia are frequent, nor to the uppermost fresh-water strata forming the bottom of a large part of the Haarlem Lake, in which it is not pretended that such acids occur.

The primitive inhabitants of the Valley of the Somme may have been too wary and sagacious to be often surprised and drowned by floods, which swept away many an incautious elephant or rhinoceros, horse and ox. But even if those rude hunters had cherished a superstitious veneration for the Somme, and had regarded it as a sacred river (as the modern Hindoos revere the Granges), and had been in the habit of committing the bodies of their dead or dying to its waters—even had such funeral rites prevailed, it by no means follows that the bones of many individuals would have been preserved to our time.

A corpse cast into the stream first sinks, and must then be almost immediately overspread with sediment of a certain weight, or it will rise again when distended with gases, and float perhaps to the sea before it sinks again. It may then be attacked by fish of marine species, some of which are capable of digesting bones. If, before being carried into the sea and devoured, it is enveloped with fluviatile mud and sand, the next flood, if it lie in mid channel, may tear it out again, scatter all the bones, roll some of them into pebbles, and leave others exposed to destroying agencies; and this may be repeated annually, till all vestiges of the skeleton may disappear. On the other hand, a bone washed through a rent into a subterranean cavity, even though a rarer contingency, may have a greater chance of escaping destruction, especially if there be stalactite dropping from the roof of the cave or walls of a rent, and if the cave be not constantly traversed by too strong a current of engulfed water.

- ↑ For detailed sections and maps of this district, see Prestwich, Philosophical Transactions, 1860, p. 277.

- ↑ D'Archiac, Histöire des Progrès, &c., vol. ii. p. 154.

- ↑ Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, London, vol. xvi. p. 471.

- ↑ Musée Société Roy. d'Emulation d'Abbeville, 1834, p. 197.

- ↑ Principles of Geology.

- ↑ For fig. 20, I am indebted to M.Lartet, and fig. 18 will be found in his paper in Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, Mars 1859. Fig. 19 is from Fauna Sivalensis, Falconer and Cautley.

- ↑ Principles of Geology, 9th ed. p. 220.

- ↑ See Chapter XII.

- ↑ Prestwich, Memoir read to Royal Society, April 1862.