Ghost Stories/Volume 2/Number 1/The Man Who Died Twice

The Man Who Died Twice

By Frank Belknap Long, Jr.

In Death as

in Life Hazlitt

was futile,

spineless, in-

effectual.

Then came

one glorious

opportunity

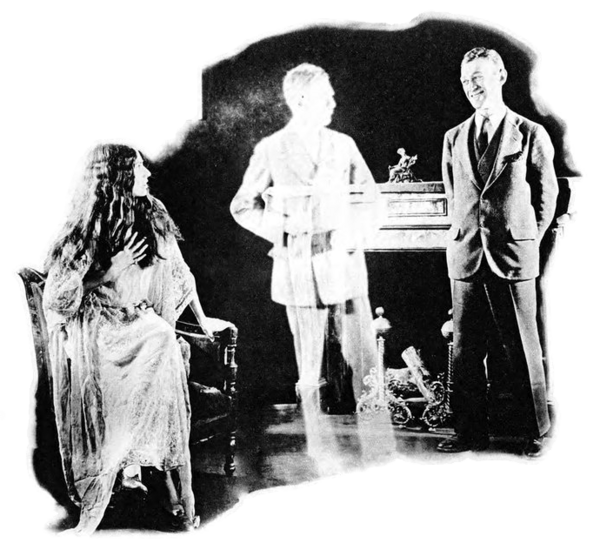

"Something has come between us,” said Hazlitt’s wife, "I feel it like a physical presence.”

When Hazlitt saw the stranger at his desk his emotions were distinctly unpleasant. “Upcher might have given me notice,” he thought. “He wouldn’t have been so high-handed a few months ago!”

He gazed angrily about the office. No one seemed aware of his presence. The man who had taken his desk, was dictating a letter, and the stenographer did not even raise her eyes. “It’s damnable!” said Hazlitt, and he spoke loud enough for the usurper to hear; but the latter continued to dictate: “The premium on policy 6284 has been so long overdue”

Hazlitt stalked furiously across the office and stepped into a room blazing with light and clamorous with conversation. Upcher, the President, was in conference, but Hazlitt ignored the three directors who sat puffing contentedly on fat cigars, and addressed himself directly to the man at the head of the table.

“I’ve worked for you for twenty years,” he shouted furiously, “and you needn’t think you can dish me now. I’ve helped make this company. If necessary, I shall take legal steps”

Mr. Upcher was stout and stern. His narrow skull and small eyes under heavy eyebrows, suggested a very primitive type. He had stopped talking and was staring directly at Hazlitt. His gaze was icily indifferent—stony, remote. His calm was so unexpected that it frightened Hazlitt.

The directors seemed perplexed. Two of them had stopped smoking, and the third was passing his hand rapidly back and forth across his forehead. “I’ve frightened them,” thought Hazlitt. “They know the old man owes everything to me. I mustn’t appear too submissive.”

“You can’t dispose of me like this,” he continued dogmatically. “I’ve never complained of the miserable salary you gave me, but you can’t throw me into the street without notice.”

The President colored slightly. “Our business is very important” he began.

Hazlitt cut him short with a wave of his hand. “My business is the only thing that matters now. . . . I want you to know that I won’t stand for your ruthless tactics. When a man has slaved as I have for twenty years he deserves some consideration. I am merely asking for justice. In heaven’s name, why don’t you say something? Do you want me to do all of the talking?”

Mr. Upcher wiped away with his coat sleeve the small beads of sweat that had accumulated above his collar. His gaze remained curiously impersonal, and when Hazlitt swore at him he wet his lips and began: “Our business is very important”

Hazlitt trembled at the repetition of the man’s unctuous remark. He found himself reluctant to say more, but his anger continued to mount. He advanced threateningly to the head of the table and glared into the impassive eyes of his former employer. Finally he broke out: "You’re a damn scoundrel!”

One of the directors coughed. A sickly grin spread itself across Mr. Upcher's stolid countenance. “Our business, as I was saying”

Hazlitt raised his fist and struck the president of the Richbank Life Insurance Company squarely upon the jaw. It was an intolerably ridiculous thing to do, but Hazlitt was no longer capable of verbal persuasion. And he had decided that nothing less than a blow would be adequate.

The grin disappeared from Mr. Upcher’s face. He raised his right hand and passed it rapidly over his chin. A flash of anger appeared for a moment in his small, deep-set eyes. "Something I don’t understand,” he murmured. "It hurt like the devil. I don’t know precisely what it means!”

"Don’t you?” shouted Hazlitt. "You’re lucky to get off with that. I’ve a good mind to hit you again.” But he was frightened at his own violence, and he was unable to understand why the directors had not seized him. They seemed utterly unaware of anything out of the ordinary: and even Mr. Upcher did not seem greatly upset. He continued to rub his chin, but the old indifference had crept back into his eyes.

"Our business is very important” he began.

Hazlitt broke down and wept. He leaned against the wall while great sobs convulsed his body. Anger and abuse he could have faced, but Mr. Upcher’s stony indifference robbed him of manhood. It was impossible to argue with a man who refused to be insulted. Hazlitt had reached the end of his rope: he was decisively beaten. But even his acknowledgment of defeat passed unnoticed. The directors were discussing policies and premiums and first mortgages, and Mr. Upcher advanced a few commonplace opinions while his right hand continued to caress his chin.

“Policies that have been carried for more than fifty years,” he was saying, “are not subject to the new law. It is possible by the contemplated”

Hazlitt did not wait for him to finish. Sobbing hysterically he passed into the outer office, and several minutes later he was descending in the elevator to the street. All moral courage had left him; he felt like a man who has returned from the grave. He was white to the lips, and when he stopped for a moment in the vestibule he was horrified at the way an old woman poked at him with her umbrella and actually pushed him aside.

The glitter and chaos of Broadway at dusk did not soothe him. He walked despondently, with his hands in his pockets and his eyes upon the ground. "I’ll never get another job.” he thought. "I’m a nervous wreck and old Upcher will never recommend me. I don't know how I’ll break the news to Helen.”

The thought of his wife appalled him. He knew that she would despise him. "She’ll think I’m a jellyfish,” he groaned. "But I did all a man could. You can’t buck up against a stone wall. I can see that old Upcher had it in for me from the start. I hope he chokes!”

He crossed the street at 73rd Street and started leisurely westward. It was growing dark and he stopped for a moment to look at his watch. His hands trembled and the timepiece almost fell to the sidewalk. With an oath he replaced it in his vest. “Dinner will be cold,” he muttered. “And Helen won’t be in a pleasant mood. How on earth am I going to break the news to her?”

When he reached his apartment he was shivering. He sustained himself by tugging at the ends of his mustache and whistling apologetically. He was overcome with shame and fear but something urged him not to put off ringing the bell.

He pressed the buzzer firmly, but no reassuring click answered him. Yet—suddenly he found himself in his own apartment. “I certainly got in,” he mumbled in an immeasurably frightened voice, "but I apparently didn’t come through the door. . . . Or did I? I don't think I'm quite well."

He hung up his hat and umbrella, and walked into the sitting room. His wife was perched on the arm of his Morris chair, and her back was turned towards him. She was in dressing gown and slippers, and her hair was down. She was whispering in a very low voice: "My dear; my darling! I hope you haven't worked too hard to-day. You must take care of your health for my sake. Poor Richard went off in three days with double pneumonia.

Hazlitt stared. The woman on the chair was obviously not addressing him, and he thought for an instant that he had strayed into the wrong apartment and mistaken a stranger for his wife. But the familiar lines of her profile soon undeceived him, and he gasped. Then in a blinding flash he saw it all. His wife had betrayed him, and she was speaking to another man.

A woman passed

through him. "Hor-

rible!" he groaned.

"There isn't any-

thing to me

at all! I'm

worse than a

jelly fish!"

Hazlitt quickly made up his mind that he would kill his wife. He advanced ominously to where she sat, and stared at her with furious, bloodshot eyes. She shivered and glanced about her nervously. The stranger in the chair rose and stood with his back to the fireplace. Hazlitt saw that he was tall and lean, and handsome. He seemed happy, and was smiling.

Hazlitt clenched his fist and glared fiercely at this intruder into his private home.

"Something has come between us," said Hazlitt's wife in a curiously distant voice. "I feel it like a physical presence. You will perhaps think me very silly."

The stranger shook his head. "I feel it too," he said. "It's as if the ghost of an old love had come back to you. While you were sitting on the chair I saw a change come over your face. I think you fear something."

"I'll make you both fear something!" shouted Hazlitt. He struck his wife on the face with his open hand. She colored slightly and continued to address the stranger. "It's as if he had come back. It is six months to-night since we buried him. He was a good husband and I am not sure that I have reverenced his memory. Perhaps we were too hasty, Jack!"

Hazlitt suppressed an absurd desire to scream. The blood was pounding in his ears, and he gazed from his wife to the stranger with stark horror. His wife's voice sent a flood of dreadful memories welling through his consciousness.

He saw again the hospital ward where he had spent three days of terrible agony, gasping for breath and shrieking for water. A tall doctor with sallow bloodless cheeks bent wearily above him and injected something into his arm. Then unconsciousness, a blessed oblivion wiping out the world and all its disturbing sights and sounds.

Later he opened his eyes and caught his wife in the act of poisoning him. He saw her standing above him with a spoon, and a bottle in her hand, on which was a skull and crossbones. He endeavored to rise up, to cry out, but his voice failed him and he could not move his limbs. He saw that his wife was possessed of a devil and primitive horror fastened on his tired brain.

He made dreadful grimaces and squirmed about under the sheets, but his wife was relentless. She bent and forced the spoon between his teeth. "I don't love you," she laughed shrilly. "And you're better dead. I only hope you won't return to haunt me!"

Hazlitt choked and fainted. He did not regain consciousness but later he watched his body being prepared for burial, and amused himself by thinking that his wife would soon regret her vileness. "I shall show her what a ghost can do!" he reflected grimly. "I shall pay her for this! She won't love me when I'm through with her!"

There had followed days of confusion. Hazlitt forgot that he was only a ghost, and he had walked into his old office and deliberately insulted Mr. Upcher. But now that his wife stood before him memories came rushing back.

He was a thin, emaciated ghost, but he could make himself felt. Nothing but vengeance remained to him, and he did not intend to forgive his wife. It was not in his nature to forgive. He would force a confession from her, and if necessary he would choke the breath from her abominable body. He advanced and seized her by the throat.

He was pressing with all his might upon the delicate white throat of his wife. He was pressing with lean, bony fingers; his victim seemed sunk into a kind of stupor. Her eyes were half-shut and she was leaning against the wall.

The stranger watched her with growing horror. When she began to cough he ran into the kitchen and returned with a glass of water. When he handed it to her she drained it at a gulp. It seemed to restore her slightly. “I can’t explain it,” she murmured. “But I feel as if a band were encircling my throat. It is hot in here. Please open the windows!”

The stranger obeyed. It occurred to Hazlitt that the man really loved his wife. “Worse luck to him!” he growled, and his ghostly voice cracked with emotion. The woman was choking and gasping now and gradually he forced her to her knees.

“Confess,” he commanded. “Tell this fool how you get rid of your husbands. Warn him in advance, and he will thank you and clear out. If you love him you won't want him to suffer.”

Hazlitt’s wife made no sign that she had heard him. “You’re doing no good at all by acting like this!” he shouted. “If you don’t tell him everything now I'll kill you! I'll make you a ghost!”

The tall stranger turned pale. He could not see or hear Hazlitt but it was obvious that he suspected the presence of more than two people in the room. He took Hazlitt's wife firmly by the wrists and endeavored to raise her.

“In heaven’s name what ails you?” he asked fearfully. You act as if someone were hurting you. Is there nothing that I can do?”

There was something infinitely pathetic in the woman’s helplessness. She was no longer able to speak, but her eyes cried out in pain. . . . The stranger at length succeeded in aiding her. He got her to her feet, but Hazlitt refused to be discouraged. The stranger's opposition exasperated him and he redoubled his efforts. But soon he realized that he could not choke her. He had expended all his strength and still the woman breathed, A convulsion of baffled rage distorted his angular frame. He knew that he would be obliged to go away and leave the woman to her lover. A ghost is a futile thing at best and cannot work vengeance. Hazlitt groaned.

The woman beneath his hands took courage. Her eyes sought those of the tall stranger. “It is going away; it is leaving me,” she whimpered. “I can breathe more easily now. It is you who have given me courage, my darling."

The stranger was bewildered and horrified. “I can’t understand what’s got into you,” he murmured. “I don’t see anything. You are becoming hysterical. Your nerves are all shattered to' pieces.”

Hazlitt’s wife shook her head and color returned to her checks. “It was awful, dearest. You cannot know how I suffered. You will perhaps think me insane, but I know he was back of it. Kiss me darling; help me to forget.” She threw her arms about the stranger’s neck and kissed him passionately upon the lips.

Hazlitt covered his eyes with his hand and turned away with horror. Despair clutched at his heart. “A futile ghost.” lie groaned. “A futile, weak ghost! I couldn't punish a fly. Why in heaven’s name am I earthbound?”

He was near the window now, and suddenly he looked out. A night of stars attracted him. “I shall climb to heaven,” he thought. “I shall go floating through the air, and wander among the stars. I am decidedly out of place here.”

It was a tired ghost that climbed out of the window, and started to propel itself through the air. But unfortunately a man must overcome gravitation to climb to the stars, and Hazlitt did not ascend. He was still earthbound.

He picked himself up and looked about him. Men and women were passing rapidly up and down the street but no one had apparently seen him fall.

“I’m invisible, that’s sure,” he reflected. “Neither Upcher, nor the directors nor my wife saw me. But my wife felt me. And yet I’m not satisfied. I didn’t accomplish what I set out to do. My wife is laughing up her sleeve at me now. My wife? She has probably married that ninny, and I hope she lives to regret it. She didn’t even wait for the grass to cover my grave. I won’t trust a woman again if I can help it.”

A woman walking on the street passed through him. “Horrible!” he groaned.

“There isn’t any thing to me at all! I'm worse than a jellyfish!”

An entire procession of men and women were now passing through his invisible body. He scarcely felt them, but a few succeeded in tickling him. One or two of the pedestrians apparently felt him; they shivered as if they had suddenly stepped into a cold shower.

“The streets are ghostly at night.” someone said at his left elbow, "I think it's safer to ride.”

Hazlitt determined to walk. He was miserable, but he had no desire to stand and mope. He started down the street. He was hatless and his hair streamed in the wind. He was a defiant ghost, but a miserable sense of futility gripped him. He was an outcast. He did not know where he would spend the night. He had no plans and no one to confide in. He couldn’t go to a hotel because he hadn’t even the ghost of money in his pockets, and of course no one could see him anyway.

Suddenly he saw a child standing in the very center of the street, and apparently unaware of the screaming traffic about him. An automobile driven by a young woman was almost on top of the boy before Hazlitt made up his mind to act.

He left the sidewalk in a bound and ran directly towards the automobile. He reached it a second before it touched the child, and with a great shove he sent the near-victim sprawling into a zone of safety. But he could not save himself. The fender of the car struck him violently in the chest; he was thrown forward, and the rear wheels passed over his body.

For a moment he suffered exquisite pain; a great weight pressed the breath from his thin body. He clenched his hands, and closed his eyes. The pain of this second death astonished him; it seemed interminable. But at length consciousness left him; his pain dissolved in a healing oblivion.

The child picked himself up and began to cry. “Someone pushed me," he moaned. “I was looking at the lights and someone pushed me from behind."

The woman in the car was very pale. “I think I ran over someone," she said weakly. “I saw him for a moment when I tried to turn to the left. He was very thin and worn." She turned to those who had gathered near. “Where did you carry him to?" she asked.

They shook their heads. “We didn't see anyone, madam! You nearly got the kid though. Drivers like you should be hanged!"

A policeman roughly elbowed his way through the crowd that was fast gathering. “What’s all this about?" he asked. “Is anyone run over?"

The woman shook her head. “I don’t know. I think I ran over a tramp. . . . a poor, thin man he was. . . . the look in his eyes was terrible. . . . and very beautiful. I. . . . I saw him for a moment just before the car struck him. I think he wanted to die."

She turned again to the crowd. “Which of you carried him away?" she asked tremulously.

“She’s batty," said the policeman. “Get out of here you!" He advanced on the crowd and began dispersing them with his club.

The woman in the car leaned over and looked at the sidewalk, a puzzled, mystified expression on her pale features.

“No blood or anything,” she moaned. “I can’t understand it!"