Golden Fleece (magazine)/Volume 1/Issue 2/Bunyips in the Mulga

Bunyips in the Mulga

| by Anthony M. Rud | Illustrated by |

All of a sudden, as they passed through a ten-foot thicket of wattle, hideous yells sounded and a shower of spears flew.

Chapter I

Two Yanks

Across the dry beds of the Salt Lakes, thirty miles northeast of Kalgoorlie, the bearded, dust-grayed driver of a spring wagon halted his weary pair of horses. He unhitched and made desert camp.

Through binoculars he carefully scanned the desert sunset horizon. Not even a dust puff raised by some lolloping, lone kangaroo, showed above the sand and stunted mulga scrub.

The bearded messenger nodded silent satisfaction. He had been careful to keep his starting time a secret. That was the chief reason why he had made so many safe trips between the bank at Kalgoorlie, and the new dry placer camp of Kargie. The last two weeks, however, there had been rumors. The giant, black-bearded inhuman monster, Paxton Trenholm, had been glimpsed not far away, leading his camel-riding Malay murderers from the North.

This bushranger, Paxton Trenholm, for all his awesome fits of madness and violence, had uncanny sources of information regarding mine bullion, payrolls, and even the occasional lucky finds made far north on the pearl beaches. He had a way of turning up and looting, where the honeypot of wealth was stickiest.

There were thirty-one separate rewards on Trenholm's head.

The dusty messenger, Tom Varney, took two water cans, a galvanized pail and a sack of oats from the back of the wagon, now he believed it safe to stay here. He cared for the horses. Then he brought out a Primus stove, and prepared a frugal meal of tea and damper for himself.

Packing away everything, since he intended to start at first streaks of dawn, and breakfast in Kargie, he put both hands reassuringly upon a small, oblong chest hidden under the seat. It was made of teak, brassbound and held closed by three Yale padlocks. The duplicate keys to these locks were at Kalgoorlie and Kargie. The messenger never carried them on his person.

Ten minutes later he made a blanket bed which would have looked familiar to an American cowboy—which Tom Varney had been, years back. In a few minutes more, he slept.

His camp-making had been watched. From the crest of a low sand dune more than a mile away, a black-bearded man wriggled back into the hollow where the camels were lying and men crouching. The bushranger, Paxton Trenholm, closed his folding brass telescope and put it away in its leather case.

"All top-hole," he said with satisfaction. "We'll give him an hour to be snoring. It will be pitch dark then. Keep those camels lying down, and don't let them grunt and groan too loudly."

The sleeping messenger, Tom Varney, never had a chance. He awoke suddenly to find the weight of a squat, muscled Malay on his chest, and the sharp blade of a kris at his throat. At a distance of three yards stood a tall, black-bearded; well proportioned white man who held a dark lantern now unhooded. In his other hand a revolver slanted, aimed at Tom's head.

"We have no particular need to kill you, Varney," said Trenholm, sounding negligent and rather haughty with his English public school accent. "So turn over obediently like a good lad, and let us bind your wrists."

Gritting his teeth in savage, hopeless anger, the messenger was forced to comply. He knew it was a mere whim on this madman's part, that he still breathed. Trenholm was like that—a paranoiac whose fits of murderous insanity came in cycles. In between rampages he was known to be quiet, cultured of manner, almost sane. Varney said nothing at all, as he was trussed with skill—albeit loosely enough so he could work free in the course of an hour or two.

They paid him no more attention then. While the Malays and the sevenfoot, skinny blackfellow servant got their camels, Paxton Trenholm harnessed the horses and drove away into the night. Helpless, writhing against his bonds, Tom Varney had to let them get away with the treasure entrusted to his keeping.

Tom took a deep breath, and then started to work free. But even when he succeeded, what then? In the brassbound teak box had been the money of other men, slightly more than nine thousand dollars, brought back in payment for the pokes of new gold sent in his care to Kalgoorlie by the dry-placer miners of Kargie.

Was there any chance at all that these rough miners would believe his story, and forgive the loss?

Their curt, angry answer was given at nightfall, when Tom arrived. Growling a beginning frenzy of disbelief, threatening a rope, they threw the unlucky messenger into his own corrugated iron shack, and padlocked the door.

At the rude barrel house which served Kargie as a pub, an angry meeting started. Tom had a few friends, but only a few—due to the fact that he was a Yank. The friends did not have much to say. They had known him

"We have no particular need to kill you, Varney, so turn, over obediently like a good lad."

as taciturn, and a good shot with revolver and rifle. They knew he had come from a far-off place called Texas, and that he was thirty-two years old. Not much in that on which to build a defense. Except the one noted and peculiar fact that Yanks did not seem to lie. Not the way Chinks or Cockneys did, anyhow. Tom Varney, of course, had sworn harshly that his tale was true. The police might have been ready to believe. Not these men.

When the crowd had drunk itself into a lynching fury, and had come surging to the iron shack after Tom Varney, they found a hole burrowed under on? wall, and the prisoner gone. That tore it.

He had left one scribbled letter, with the plea that it be mailed to his kid brother back in Texas. The letter read:

Dear Sam:

I'm damn glad you stayed on the ranch. I'm in bad trouble. They say I stole about nine thousand dollars. Acourse its a lie, but I cant prove it, lessen I can bring in the head of Paxton Trenholm in a sack. Likely I'll lose out, but anyhow I aint being taken alive by police or anybody. And I aim to get Trenholm.

Goodbye, kid. Love,

Tom.

The police took charge of the letter. After a time it occurred to someone that it might be a good idea, after all, to keep other Yank Varneys out of Australia. So the police did mail the letter to Sam Houston Varney, at Sweetwater, Texas, with a grimly explanatory enclosure—stating their case against Tom.

But if their intention was to keep young Sam out of the Antipodes, they had adopted exactly the wrong tactics. Within a week after receiving that horrible message, Sam had sold the paternal ranch and small herd, and was on the Pacific Ocean bound for Melbourne—and more trouble than he ever dreamt existed.

Two months had passed. The hunt for Tom Varney had subsided. Then it was a tall, bronzed, gray-eyed young man in a broad-brimmed black hat, presented himself at the headquarters of the West Australian Provincial Police, at Kalgoorlie. Sam Varney had reached there by railroad, but had found it practically impossible to go one step further toward the mine town of Kargie. Larrikins, indigent prospectors, and men hauling liquor, made the trip. But Sam Varney was not accompanying any of these—not until the money in his belt had been put down on the line for a certain purpose.

"I'm Tom Varney's brother—you'll remember, I reckon, a man named Tom Varney?" he said quietly to the policeman.

"Hm. Yes, we remember Tom Varney. Why?"

"He's accused of stealing $9,200," was the reply. "That's a lie. However, till I can prove it ain't true, here's all of the money I c'd raise. You'll find $8,500 there. Also there's my I. O. U. for $700. I'll take that up soon's I can. G'bye."

And dropping the money belt before the astonished officer, Sam Houston Varney strode out of the office, paying no heed to the voices which called after him.

"Well—I'm an emu's uncle!" gasped the desk policeman. Or words to that effect. "Perhaps we don't need to worry about keeping Varneys from Texas out of Australia, after all?"

"There's lots worse than Yanks," admitted a brother officer with extreme tolerance. "Wonder what he's going to do to raise that extra seven hundred? Rob a bank?"

Like many plainsmen, young Sam Varney had been impressed and thrilled by his crossing of the ocean. He decided to try a job on a coaster for a while, till he got his bearings. One thing was sure. He did not want any of the dry goldfields—which were said to be petering out, anyhow.

He had met a sea captain, and the latter, glad indeed to get a hand in these days when men were scarce, had told him to come along and meet the Narwhal at Freemantle. Sam, of course, had not the slightest idea of the reputation along the coast of the tramp freighter Narwhal, or of the even less savory things said about Captain Moebus and the tow-headed Axel Larssen, his mate.

There is no use going into a log of his experience. First he was robbed of his few possessions. Then he was beaten in three plucky but hopeless fights with the captain and mate. Bruised, sore, sometimes unconscious, he was tied up every time the Narwhal made a regular port. Not until they put in, several weeks later, at a small island near shore in the Bight, did Sam have any chance to escape.

They did not tie him this time. What use? The Bight swarmed with sharks. Even if a man made shore, there was nothing at all in front of him but waterless desert. On the tiny island, of course, there was no chance to escape. There was only a beachcomber's hut or two—and with these Captain Moebus had a little nefarious business with contraband.

When the captain and mate had gone ashore to transact it, Sam looked longingly at the mainland shore. Less than a mile away. He thought he could make it—and did not think at all about what he might find, if he proved successful. Taking his chance when other members of the crew were below, he dove from the side, and swam hand over hand for the desert shore.

An hour later the captain and mate, returning, made sure he was not on board. There was no small boat missing. The answer seemed plain.

"Good riddance!" snarled Captain Moebus. "The white-pointers 'ave 'ad a meal!"

He was wrong. Just twenty minutes earlier Sam Varney had hauled himself to the sandy, barren shore of the Bight. He was near the point of complete exhaustion from his long swim, and the physical batterings received before. But no shark had noticed him.

Chapter II

Monsters in the Mulga.

The first thing the Yank saw, when the smart of salt was out of his eyes, was a fence. It was a good strong fence, built of close mesh—not barbed wire. It came right down and ended at a stout pile driven in below tide marks.

Sam grinned at it, and sat down beside it to rest. Time had been, back on the Panhandle range, when he had cursed fences. Now one looked like a friendly and familiar thing. Prob'ly a ranch or sheep station right near, he said to himself drowsily. He slid slowly over on one side and slept.

Two hours later from the west came six swift camels—racing maharis, not the undersized, slow creatures used by Afghans here. One camel carried packs. It was led by a tall, skinny blackfellow on another camel. This was a Kimberley Lake aborigine, Paxton Trenholm's body servant.

The big white man, the notorious bushranger-madman, rode another camel. Likewise mounted, three squat, high-cheekboned Malays followed him.

They came right down to the end of the fence, and there discovered the sleeping Yank. By this time Sam had an arm over his eyes, and was snoring—the way very tired men always do when they lie on their backs.

Pistol in hand, Trenholm frowned down. Then he shrugged, and threw a shot down into the ground, so sand sprayed over Sam's face.

The sleeper grunted. His arm fell away, and his eyes came part-way open. Then he snored again. He had not really awakened, though Trenholm thought so. A queer inspiration had come to the bushranger. He shouted something to his riders, and rode down around the end of the fence, and on out of sight to the east.

An hour later he returned. The sleeper was still there. Trenholm motioned silence. Like ghosts the camels circled the fence, getting wet to their knees. Then they disappeared in the dusk, bound northwest.

Trenholm chuckled in his beard. The madness was coming on him gradually again, and he would have slain the lazy white man sleeping there—except for one thing. The police had been a little too close lately. It would help a lot to have this lazybones report that Trenholm had crossed the fence line, and gone east. If they started looking for him over in South Australia, he would have time to seek refuge with the giant blackfellows—the Aruntas, Parrabarras, or Kimberleys, among whom he was regarded as a demi-god, or more. He had riches enough for this year. He wanted a chance to lie low and foment trouble for the police and for other white men. He hated all of his own color skin.

In early dawn Sam awoke, shivering, to blink in wonder at a strange world. The first object he beheld was the fence. He got to his feet, swung his arms to start circulation, and looked along the wire in hope of seeing a building, a ranch-house. None was in sight. He shrugged philosophically, in spite of hunger and a degree of thirst from the salt water, and started to tramp northward along the friendly fence.

Funny, he had a dream about men riding camels, going around the end of the fence. Just nightmare, of course. He'd been dead tired, and still ached. The sun would be up soon, though, and it would warm up his bones. If he stuck to the fence he'd have to get somewhere sometime, wouldn't he?

Not necessarily—not within walking distance, Sam. This was like no fence you ever saw in Texas. One of the longest barriers ever built by man for any purpose, it had cost the Australian Government $1,000 a mile. There were 1,500 unbroken miles of it. It stretched from Starvation Boat Harbor in the Bight, where Sam had swam ashore, straight north across the whole continent, to Condon, on the muggy, crocodile-infested Ninety-Mile Beach!

There was not a single ranch or sheep station on its entire length. Just jungles, deserts, wastes of mulga scrub, gidgie bush, beefwood and wattle. The fence was built, and watchfully patrolled by men, for a strange but deadly serious purpose. It was meant to keep the plague of rabbits out of West Australia.

As he trudged, his garments clinging after their sea-water shrinkage, Sam thought grimly of his double task—triple task, really, for it entailed getting hold of his brother. Tom Varney had vanished so successfully that the police of all Australia had not been able to arrest him. Sam realized that nearly broke, with that $700 note to meet, he could not hope to find Tom except in one way. Get on the track of Paxton Trenholm. Somewhere, following the bushranger, trying to capture or kill him, would be that stern man of single purpose, Tom Varney.

The big white man, the notorious bushranger-madman, rode another camel.

Sam had to have a job of work, or starve. Getting something would be easy, he thought. But it would just be something temporary, to let him get oriented. Once he had a good idea of the bushranger's trail, and a stake sufficient to provide him with rifle and a mount, Sam would break loose for the manhunt. The rewards accumulated on Paxton Trenholm would repay the sum of Sam's note fifty times over.

Now he grew increasingly thirsty. In ignorance of this part of Australia, and hoping it was not like the gold deserts, he still scanned the horizon for sign of a ranch. There was none. But now in the mulga there was wild life on every hand.

Doglike creatures, dingoes, howled at him and slunk away. They haunted the fence—for a reason Sam discovered. He came upon a built-in rabbit trap. Two of the stringy, long-eared creatures were prisoners, and the dingoes had been trying to dig in to get at them.

Sam became thoughtful. He studied the unending fence, straight to the northern horizon like a railway track on the Texas plains. Then, wishing he had a drink, he unlatched the trap, took out one of the stringy jacks, killed and skinned it. His waterproof match safe held a few matches. He gathered branches of mulga, lit a fire, and spitted the tough rabbit.

"They sure go in for ranches as are ranches, out here," he muttered. "I haven't seen hide or hair of any critters, though. Doggone, but I c'd use a drink!"

Ironically the branches of thorny acacia crackled and snapped on his fire. Ironically—for unknown to Sam, the heavier stems of this mulga held pure water. Like the barrel cacti of southwestern American deserts, it was there to save the life of man or beast. It was the sole reason wallabies and other creatures could live in many thousands of square miles of this continent.

He ate the rabbit. Thumpings in the sand, and whistles of breath made him turn. There, galumphing away toward the dreary sameness of horizon, were five big kangaroos and two small joeys.

"Bunyips in the mulga!" grinned Sam dryly, recalling crew yarns of the fearsome interior. Bunyips really were imaginary monsters of lesser degree in the lodge of devils believed in by the blackfellow aborigines.

Old Mooldarbie (chief devil according to many tribes) kept him a ferocious pack of bunyips. Unless propitiated, sometimes by human sacrifice, Mooldarbie loosed these hungry scourges. Then lone blackboys, even whole (nomadic) villages disappeared.

The word nomadic really explained the disappearances; but the tall, halfstarved black aborigines are Stone Age children in their minds as well as in their weapons and manner of life.

Five minutes later Sam looked up, stopped and stared. Two dots were moving slowly and dustily down upon him from the north, riders on the west side of the fence. Sam gave a dry shout of gladness, and waved one arm like a semaphore. Maybe a drink!

The dots grew in size, and now Sam saw that here were two men actually mounted on camels! Then perhaps his odd nightmare might have been reality, after all!

Chapter III

Fence-riding Cameleer.

These mounts were the undersized Sudanese camels, brought via Kenya. They were necessities in a land where the only water for hundreds of miles was brought to the surface by artesian bores. The brutes, mean and complaining as they always were, still could go five days at a stretch in hot weather without drinking. And they could subsist when they had to on spinifex, the prickly, coarse grass of the plains.

The two bronzed riders came. They looked down wonderingly and somewhat suspiciously at a man on foot in this mulga wasteland. But Sam was too thirsty to stand on ceremony.

Howdy, strangers," he greeted, his voice little more than a croak. "Where can I get a drink of water?"

The elder of the pair, a man with lined, leathery face but clear, sun-squinted eyes, unbent a trifle. "Here's the nearest supply, friend," he answered, unbuckling a canteen and unstoppering it. "You're a long way from a well."

There was a hint of inquiry in the last, but Sam waited to gurgle down a full pint of the tepid water, which tasted better to him than champagne right then.

It would take Sam a little while to learn, but the elder of these two men was Fence Inspector Goelitz, in charge of the three southern "lengths" of the rabbit fence. The younger was Bart Jolley, a recruit fence-rider.

After the drink, Goelitz offered a cheroot from a long, narrow case. Sam accepted with a grin. "Now, I'll tell you all," he said, puffing with satisfaction, though choking momentarily on an inhalation of the strong smoke. "I s'pose you're police?"

No, not police. Goelitz explained a little, and learned Sam's name. Then Sam told briefly of his six weeks nautical experience, and mentioned the Narwhal, Captain Moebus commanding.

He probably could not have given himself any better break. The reek and stench of the Narwhal's unsavory reputation had reached both men. Anybody who could not stand Moebus and Axel Larssen, probably was a decent sort. The Inspector's manner became more cordial.

"So now I'm looking for a job. Any job at all," concluded Sam, saying nothing about his brother, or the quest of vindication.

"What can do you?" asked Goelitz. This was a form inquiry. Right then expansion in Australia was at its height, and the fence was starved for men. The Government wage was not as large as that any able-bodied man could earn with shovel and pick working for other men in the goldfields, and almost every man who could raise a grubstake was prospecting on his own anyway.

Sam told of Texas and his ranch experience. He was modest about a real ability as a rider. Also he said nothing about the accomplishment which had been his chief pride—his shooting. Yet Goelitz, looking critically at six feet of lean, bronzed American manhood, was grimly satisfied.

The Villain

"I'll take you on," he said, "if you're not shy of a fight now and then. We ride heavily armed—for good reason. The blackfellows have been troublesome of late. They're always cutting the fence to get wire frameworks for their wurleys; but lately it's worse than that. Someone or something is making bloody trouble."

"Better try me," suggested Sam, smiling. This sounded better than he had dared hope. "I'll hold up my end."

"Very good!" snapped Goelitz. "Then, this is the job!" He explained tersely.

Sixty years earlier a misguided Queensland larrikin brought ashore four mated pairs of rabbits. They promptly escaped into the mallee of the eastern coast. Now the descendants of those eight bunnies numbered millions, perhaps billions. They had overrun and practically ruined all the agricultural and grazing lands of the eastern half of the continent, despite the several kinds of deadly warfare carried on against them.

There was a reward of $150,000 and five square miles of any unoccupied land in Australia waiting for the man who suggested a plan for controlling the rabbit plague. The great scientist, Louis Pasteur, had been employed in the hope of working out a bacterial method of extermination. Even he had been forced to surrender.

Meanwhile, this fence was to shut out rabbits from the rich agricultural areas of the southwest, where the plague had not yet appeared.

Sam caught his breath at thought of such a reward. There was a fugitive thought of importing American coyotes to prey on the rabbits, but it vanished. Coyotes could be worse than rabbits, especially in a land where valuable Merino sheep were raised in enormous herds. And then Sam caught himself sharply. No matter what else happened, he had to find his brother Tom, and help the elder snare Paxton Trenholm and vindicate self-respect before the world.

"You'll work hard, and live for the fence!" concluded the inspector. "You'll fight for it—and I may as well warn you right now that ten or more riders in the north sections have been killed by blackfellows in the past six months!"

"Fine!" said Sam. "When do I start north?"

"You'll stay right here with me in the south for now," said Goelitz. "There are troubles enough here without hunting new ones."

He clasped hands with Sam, as did Bart Jolley—the latter smiling genuine welcome to a personable companion of his own age.

The three of them, however, little suspected that trouble brewed by a madman, even at that moment, was gathering for them—at a spot in the gidgie bush less than thirty miles away.

Chapter IV

Death in the Gidgie

The first day, clinging to the bony rump of the inspector's camel, Sam was broken in to the work. With Bart Jolley, they headed south for the few miles Sam had trudged, examining each post, each yard of wire, killing and skinning the rabbits found in the traps, making sure that repair materials were in the hidden caches away from the fence.

(When the blackfellows found these caches they stole everything.)

"I s'pose," observed Sam, "all east and west travellers have trouble getting through. Prob'ly have to go clear down and around the end of the fence, eh?"

"Hm. Traffic isn't what you'd call heavy."

"I saw five-six jiggers on camels last night, headin' east."

"Eh? What's that?" Goelitz suddenly tensed, looking backward over his shoulder. "You saw—what?"

Sam explained that he might have dreamed it, but he thought he had seen a tall white man with a black beard, a skinny blackfellow, and some squatty brown men, all on camels, ride eastward around the end of the fence.

"Paxton Trenholm!" burst out Bart Jolley. "Going east!"

"That means that maybe West Australia is rid of him at last!" breathed Goelitz, not noticing that Sam's hands suddenly had clenched till the knuckles came white. "Also it means we hump it to Murriguddury, where I can get on the end of a telephone wire!"

But despite this excited phoning which Goelitz did, as soon as they reached the supply point of Murriguddury three miles west of the fence end, they never found Paxton Trenholm in South Australia. Scores of police hunted him, but he lay back in a village of the Parrabarras, west of the wire. He was planning, with cold fury, greater trouble for the white men than he ever had caused.

Goelitz also called up the provincial police, asking as a matter of routine if they had anything against a young man named Sam Houston Varney, his new rider.

When he came back there was a peculiar light, almost of respect, in his eyes. But he said nothing. He outfitted Sam with clothes, rifle, revolver, ammunition, canteens and a swag (saddle roll of blankets, cooking utensils, with salt, sugar, pepper, tea and two cans of condensed milk). Then they picked him out a mangy camel, and a saddle, both decidedly shopworn in appearance.

The more permanent parts of his outfit would go north by the next bullockie train (supply wagons, drawn by six yoke of oxen apiece, each driven by a bullockie). A railroad had started northeast from Adelaide, but it had not got far as yet. The greater part of the fence was supplied from the north and south by these ox-wagons.

Sam himself was rather white under the bronze of his cheeks. His eyes were grave. If this had been Paxton Trenholm, indeed, then should not he, Sam, try for another job in South Australia? It was fortunate for him that the stark need of eating and living forced him to shelve that idea for the time being.

He finally told the story briefly and passionately to Goelitz, warning the latter that probably he would have

to quit him some day when he had a fair stake, to take up the long hunt for Trenholm and Tom Varney.

"I 'spect Tom's dead by now, or he'd have got Trenholm," said Sam. "Just the same, we Varneys stick to what we start. That's why I'm warning you, Goelitz."

"I'm glad to have you, Sam, as long as you can stay," said the Inspector, and meant it. A young man, Yank or otherwise, who would sell all his possessions to help square up an unjust debt of an elder brother was a new experience. Goelitz warmed to his recruit rider, and privately hoped that the police would catch or kill the bushranger shortly, so Sam could stay on indefinitely.

There was a contract-sameness about the great fence, as Sam learned in the days that followed. Each one hundred miles was called a "length." It was supposed to be patrolled by two riders. In the middle of each length was an artesian well, and a corrugated iron shack which the riders used as headquarters.

The inspectors, of whom there were five, each had charge of three fence lengths. Each inspector had a fairly comfortable cabin placed near the artesian well on the middle length of his division. It was possible for an inspector to marry. Two of them had done so.

Men were short now. Bart Jolley had the southernmost length to himself. Goelitz and Sam left him at the northern boundary. A ratty, mean-eyed fellow was met now, Koken by name. Goelitz passed him with only a few inquiries, evidently not caring much for his company. But after they had got further along, expecting to meet the second rider of this length, Goelitz began to worry.

"Don't like it," he frowned, scanning the northern horizon. "Morrison's a good man. He ought to've met us this noon—five hours ago. I think we'll wait tucker an hour, and see if he doesn't show up. There's a dust storm coming," he added, peering through his binoculars. "Not a real hell-roarer like we get sometimes, though."

The coming of the wind, with its load of stinging, suffocating particles, made them seek shelter in a thick growth of golden wattle. An hour passed, then the wind died, and they could light a fire for tea and damper. It was too late to go further. They camped right there, and the missing cameleer did not arrive.

Next morning they had breakfasted early, and gone two miles on their way when they came upon a saddled camel The beast was grazing, untethered.

"This is bad," worried Goelitz. "I hope it's only an accident. But we have to find Morrison right away." His eyes were searching the almost impenetrable scrub to his left. He lifted his rifle from the boot, and levered a cartridge into the chamber.

Sam Varney did the same. He also unbuttoned the dust flap of his revolver holster, and buttoned it back out of the way of a quick draw. Easing the heavy revolver up and down in leather, he tested the feel of the grip, and the balance. Not as good as his old Colt, but a serviceable weapon with smashing power.

A sudden cry burst from the inspector's throat. They had come to a glade-like pocket which stretched back some eighty feet into the wall of scrub. There were the evidences of a one-man camp. A dead cooking fire. A scattering of effects mauled through by blacks. And on his face, one arm outstretched forward, lay what was left of Morrison, the cameleer!

Dismounting hurriedly, the two men ran to the body. Goelitz cursed savagely, going down to one knee. The body had been mutilated in horrible fashion.

"Look out!" suddenly shouted Sam, who had been fidgeting uneasily. He had glimpsed a tell-tale movement in the scrub.

That second spears whizzed!

With his split-second of warning, Sam was able to plunge sidewise, slapping down his palm in a fast draw almost as good as he had been capable of in Texas days.

His revolver crashed—once, twice, thrice—and then as he ducked a spear, a fourth time. He had the hot satisfaction of seeing two cortorted and hideously painted black faces, suddenly disappear. A third leapt upward with a howl, then fell back at Sam's last shot.

The scrub shook frenziedly as one survivor—possibly wounded—left the scene as fast as his legs would carry him. The attack was over.

Restraining the impulse to dash in pursuit, Sam turned to his companion. Goelitz was down on hands and knees, half-fainting from pain. An obsidian lance had transfixed his right thigh from the rear.

"Just let me alone—one minute. Then—help!" gasped Goelitz.

Sam nodded, understanding. Swiftly reloading his revolver, he went cautiously into the scrub. Nothing seemed to move there now.

But at that moment something whizzed up from the ground, aimed at his head! A stone-weighted waddy!

It was thonged to the wrist of a blackfellow who lay there, frothing blood from a chest wound, but malignant to the last.

Sam dodged, managing to throw up his left arm and deflect the blow which otherwise might have brained him. Leaping back, he aimed the revolver—but did not fire. That one effort had been the last for the aborigine. Now he shuffled his skinny legs in the leaves, shuddered all over twice, and lay still.

There was a second white-striped body spread-eagled across a bush, which bent under the weight. And two yards further a third blackfellow with yellow circles painted on his cheeks sat with head slumped forward to his chest, and both arms clasped about his mid-section.

Varney went back to his wounded chief. "Three of 'em accounted for," he reported, "and I think I tagged a fourth. Ready for me to cut off that spearhead and pull it out of the hole?" He opened his keen-bladed jackknife.

"Go ahead. It can't hurt worse 'n it does!" bade Goelitz, white-lipped. He gripped his thigh with both hands to squeeze the nerves. "Wish to hell I had a spot of wheat whiskey!"

Sam, knowing a little of range surgery, was careful and deft. Just the same, Goelitz fainted when the spear was pulled out. By the time he returned to consciousness, Sam had the wounds bound tightly, and was riding the rump of the inspector's camel, leading two more, and holding Goelitz in the saddle before him.

Thus they reached Goelitz's own comfortable cabin, and that night the inspector told Sam that he was to take over this length of mulga and gidgie in place of the dead Morrison.

Chapter V

Molongo Corroborree

The recruit cameleer had cooked himself ten kettles of soup from the tails of young kangaroos, and was well on his way to becoming a seasoned rider before he had another encounter with the blackfellows. Aruntas and Parrabarras roamed this region, and until this year they had been friendly enough—if troublesome as thieves.

Sam did his job. It was absorbingly interesting to him. But every man he met—the bullockies who came with supplies, the Afghan camel couriers, the railway engineers who came over from the new line on the east for gossip or occasional supplies—was besieged with questions regarding Paxton Trenholm, the twentieth century bushranger.

From the men, and then from a file of old papers kept by the sour, foxfaced rider, Koken, Sam learned practically all that was known about his quarry. Trenholm was a remittance man of proud English family—one who had not deigned to change his name the way most banished men did. The scandal back home probably had been caused by one of his first maniacal rages, then unsuspected. He had been attacked by a palpably drunken man whom he did not know, and had retaliated with such fury and such giant strength that the unfortunate drunk died of a broken skull and broken jaw. The English jury had deliberated long, but finally acquitted Trenholm. His family possibly sensed the truth. They shipped him to the Antipodes.

Trenholm, with some capital to start, turned up on the northwestern pearl beaches, as a buyer. He went seasonally from Broome to Anchor, to Vesey Beach, over to Perak, and back to the Burdetts in his own power schooner.

Then one day at Highgate Mibs his recurrent insanity betrayed him. For reason unknown, possibly attempted thievery, he strangled and broke to a pulp a half-caste pearler.

That was when he went wild. He took to the scrub, murdered two provincial policemen sent after him, and got himself a roving band of Kimberley Lake blackfellows. For periods he would be quiet, and no man would see him or hear of him. Then he would start on red foray. He was out-and-out bushranger now, pearl pirate, and a sort of inhuman demi-god to the blacks and Malays.

"When his fit of madness is on him," Goelitz told Sam, "he will kill anyone of white skin he meets."

"I hope he's mad when I meet him again," said the young rider grimly, "because I'm going to shoot on sight!"

Hot weather came, bringing an oily reek of tarweed. Pests of flies made life miserable for camels and men. Inspector Goelitz was hobbling about again, taking up his duties by graduated stages.

Sam had been having his troubles. A village of Parrabarras lay about three miles west of the fence. These tall, emaciated blacks raided the fence and broke through every time Sam's back was turned. And strangely enough, they invariably attacked a certain spot just east of their village. Sam had got to the point where he hurried through every other duty in order to get back to this spot. And then usually he found a disheartening job of fence repair awaiting.

This was serious. As yet few rabbits had reached this part. Yet any day the vanguard might arrive, and enough bunnies seep through to start the plague in the west, and make the fence of no more avail.

Sam got an interpreter to help him out—he had learned a little of the aborigine dialects, but too little for extended conversation—and tried to talk to the gaunt villagers. No dice. They simply refused to say anything at all. And then immediately he returned, they picked up their whole portable array of wurleys (cone-shaped huts), and moved to within less than a mile of the sore spot in the wire!

Sam told Goelitz, and brought him to the scene. "I'm going to fix 'em next time!" the recruit announced. "Come back here and have a look at my own devil-devil. I only wish they'd start their damned bull-roarers now! I'd like you to be with me."

Goelitz frowned and followed. Like most Australians, he felt that the sooner the aborigines were exterminated, the better. But it was impossible to carry war to them.

Behind a covert of dwarf screwpines Sam Varney had concealed a ten-foot contraption of wood, canvas and paint. It was a toothy, menacing face outlined in red paint, a scarecrow whose outstretched arms could be made to flap the canvas sleeves up and down when a cord was pulled by the man carrying the whole thing. Childish, of course, but then these blacks were nothing but superstitious children.

"It might work—but then there probably would be fifty spears sticking through the middle of that nightgown," said Goelitz. "Better not risk it when you're alone, Sam. I need you."

They had no more than started back to the fence and their tethered camels, however, when a nasal, whining shriek brought them up standing. The first of the bull-roarers, the whirring handsirens which always signalled the banishment of the gins from the ceremonial circle of corroborree. Instantly a dozen more bull-roarers joined. The air quivered with that whining, nervejangling nastiness of sound.

"Reckon you got to see!" said Sam with grim satisfaction. "We've got an hour before the bucks come, but the gins 'll be down cutting wire in half that time. Le's hide the camels first."

When the sound died, the two fence men crouched down back of the screw pines. Already they could hear the far-off chattering voices of the gins. These women would come down and

do the first work. Then they would scatter when their lords and masters came.

The chattering grew to an ululating clamor of weird cries. The gins came running, scampering, leaping high in the air, turning, kicking their toothpick stilts of legs, brandishing whatever weapons or tools they had been able to gather.

They did not immediately attack the wire, but went through a seemingly endless and meaningless ceremonial capering on the far side. Sam watched intently. The conviction was growing in his mind that these raids were not for the purpose of securing wire, but for some superstitious or religious notion. Perhaps this particular spot where the wire always was cut was thought to be a special highway of the devils of the scrub.

The time grew short. Sam was impatient, wiping cold perspiration from his forehead. There was no use doing anything until the bucks came, but they were due any second. Why didn't the gins begin? They had to do most of the heavy work, anyhow.

But now high-pitched screams sounded, and as if these meant acknowledgement of permission for their work, the gins turned and charged the wire. With clubs, pick-axes stolen from caches, obsidian knives, old waddies and other implements, they went at it with an intense fervor. In a surprisingly short time the posts went down. Then the wire was hacked, bent, broken, torn away.

The white men, though cursing below their breath, did not interfere. The warriors had not come.

But then the women cried out in fear, and scattered back into hiding. When their men were painted in the vertical white stripes of Molongo corroborree, it was death for any gin to get in their way.

Naked, white-striped so they uncannily resembled skeletons, the warriors—about thirty-five in the band—converged upon the twenty-foot fence gap. They hurled spears into the ground ahead of them, yelling fiercely. Wrenched them out, hurled them again. A few brained imaginary enemies with waddies. Others sent the heavy, non-returning (though curving) war boomerangs sailing through the fence gap.

"I tell you, they're driving bunyips through the fence!" whispered Sam with sudden conviction. "Getting rid of vermin! Now my number is up!"

With that he produced a short reed horn of cardboard, clasped it in his teeth. It was the sort of horn children blow on holiday celebrations, and it gave a moaning snort intense and arresting.

Now up from the screw-pine covert flip-flapped the ludicrous scarecrow of red-painted canvas, and a hoarse, awesome sound seemed to come from its throat!

Slowly, swoopingly it appeared to fly along the ground, straight for the defiant warriors and the gap in the fence. With each flap it gave its haunting, terrible cry—

For six seconds the painted warriors stood petrified, gaping at a materialization of the most dreaded spirit of the mulga. Then shrieks and screams rent the air. Stumbling, falling in their frenzy to escape, the entire band of painted Parrabarras turned and fled. Their diminishing yells of terror floated back as they sprinted for the safety of their wurleys, a mile distant.

Sam kept going. This was going to cure the blacks, he swore. Despite a cautionary shout from Goelitz back there, he flip-flapped straight into the scrub, and kept on for about half a mile.

There the scrub thinned, and a glade opened. He stopped, planted the pole which held up the scarecrow, fixing it so it appeared to be lurking behind a low bush, ready to leap out upon any black fellow crazy enough to come near.

Satisfied, Sam started back. At the end of the glade he turned for one last glance at his handiwork—just in time to see an erect, black-bearded man on a camel, accompanied by a blackfellow likewise mounted, yank the scarecrow pole out of the ground!

Paxton Trenholm!

His eyes starting from their sockets,

Sam yanked out his revolver. But

Slowly, swoopingly it appeared to fly along the ground. . . With each flap it gave it haunting, terrible cry. . .

he did not get time to circle for a shot at decent range The two there at the other end of the glade started up their camels, and headed away in the direction of the Parrabarra village, dragging the scarecrow behind them!

On foot Sam was at a complete disadvantage. Cursing, half-praying, he turned and sprinted back to the wire. He had to have his own beast, and warn Inspector Goelitz so the latter could send police. He knew the elder man would forbid, thinking only of the fence. But even the loss of a job he thoroughly liked would not stop Sam now Here was the insane bushranger-murderer who had ruined his brother!

Chapter VI

Wanted Men

Unexpectedly, Goelitz offered no objection. There was a queer light in his eyes, and he clasped Sam's hand strongly in farewell, saying gruffly that he would send word to the police that Trenholm had doubled back, and was not in South Australia after all.

Sam was glad. He did not know, but that phone conversation Goelitz had had with the police, at the time Sam was recruited, was the reason. The inspector realized clearly that Sam would go—hell and high water notwithstanding. He was a good man, anxious to face almost certain death. Might as well be cheered on his way.

Sam whipped his camel into a shambling run, straight for the Parrabarra village. As he went he levered a cartridge into the rifle chamber. All he asked for was a chance to face Trenholm. If the other man got him, at least Sam would fling one shot—and there would be the rightful vengeance of all white men in Australia, wrapped around the nose of that bullet!

The scarecrow had worked too well. When Sam came to the native village, he found that only about one-third of the wurleys had been carried away by their blackfellow owners. The rest stood empty, deserted. In the middle of the cooking square lay the effigy of Mooldarbie, flat on his back. Trenholm probably had meant to point out to the blacks how easily they had been fooled. Finding the aborigines vanished, the bushranger had dropped the contraption in disgust.

Now the cameleer had to think. He had visited this village only a few days earlier, and was certain it had not then been used by Trenholm as a base. The bushranger, too, was reputed to surround himself with creature comforts when he deigned to pass any time in a native village. Here the wurleys were all small and poor, mere above-ground burrows.

Nothing to do but dismount and hunt camel tracks leading away. For some time, circling, Sam had no luck. If only he had a blacktracker, one of those trained natives said to be able to follow a trail too cold even for bloodhounds.

But at some distance from the village he came upon plain prints in soft sand. Five or six beasts being ridden away at a good gait.

Well, Sam followed at a walk. Twice when he tried to speed up matters, whipping his camel, he lost the spoor, and had to go back and start over. It was slow going. He ground his teeth, knowing that Trenholm and his men, up on meharis, could be putting tremendous distance between themselves and the slow pursuer, supposing they had glimpsed Sam back there in the glade.

"I'm saying they didn't!" he gritted, and kept on. Half an hour later, topping a dune like a small hill, Sam suddenly whirled his camel, made the beast kneel, then lie down as he leapt off to take cover. Just beyond, in a shallow valley, stretched the huts of a large native village. And Sam's first glance had caught one triple-sized, high-roofed wurley, surely more commodious than any Parrabarra or Arunta aborigine ever built.

Headquarters of the bushranger, Paxton Trenholm!

Taking his rifle, making sure that his revolver was loaded with six cartridges and the hammer lowered, he tossed aside his hat and bellied a way toward the crest of the dune. Just one good bead on Trenholm, and—

"Stick 'em in front of yuh, palms down!" came a low, savage voice from the rear.

Out of the scrub unseen by Sam Varney, had stalked a grotesque apparition. A white man whose graying beard was eight inches in length and blowing in all directions. A white man clad in horrible rags of indescribable filthiness.

Varney swore and sat up, instead of obeying literally. He was prodded by the barrel of the rifle in the newcomer's hands, so lifted his own thumbs ear-high.

"One of Trenholm's gang, are you?" Sam snarled, infuriated at his failure. He would die now, of course, and Trenholm probably would escape again. "Well, take it from me, I—"

The words died in his throat. Something strange and awesome had happened to the bearded brigand. A choked cry came from his throat. The bloodshot eyes fairly started from their sockets. The rifle drooped.

"My God A'mighty!" he said in a gasping whisper, clawing at his eyes with his left hand. "You, Sam! Oh, damn your hide, Sam, why did you come to Australia?"

With a gulping cry of horrified recognition, Sam was on his feet.

"Tom!" he choked, and flung arms around the wasted frame of his elder brother.

Goelitz had reached his own cabin, bathed, and was resting his wounded leg—after sending a courier with news of Trenholm to the nearest police—when a strangely clad youth tramped wearily up and got himself several dippers of water at the artesian well.

Sam still had a Winchester rifle, but no bandoleer of cartridges. No revolver or holster. On his feet were broken, worn-out relics of boots through which his toes projected. He wore the lower half of a suit of underwear, and beside that—nothing. Gone were his canteens, swag, camel and everything else!

"I s'pose I'm fired," he said when Goelitz came to him, frowning. "I ran into a desp'rate man, and this is all he left me—oh, hell, Chief, I got about $180 coming. Let me go ahead and work out what I owe for the rest of the outfit—camel and all.

"That was my brother, you see. He was almost up with Trenholm. I—I had to stake him, because there wasn't enough for two. So I—I reckon I owe the Government a lot."

"For sending Nemesis on the trail of Trenholm the bushranger?" asked Goelitz in a peculiar tone. "No, Sam. Australia has spent $50,000 and more trying to catch Paxton Trenholm. I don't believe another four hundred, more or less, will break the treasury!

"I just hope, Sam Varney, your brother is as good a man as you are!"

"Tom? Huh! Tom's the goods. You wait. Trenholm's as good as dead and buried, right now! Tom doesn't ever quit—anything."

Chapter VII

Duster girls.

A trans-continental railway was being resurveyed. On the original survey, north and south, a few miles of steel had been laid from Adelaide to Oodnadatta. From Palmerston, far north on Clarence Strait, a few miles of road had crept southward. The middle 1300 miles, however, were being changed by surveyors, bringing the line quite near the great fence.

Heavy freight and occasional passengers came by rail to Oodnadatta, thence to the bullockie lines at the fence. Sometimes the fence ox-wagons were sent over for stuff shipped up from Adelaide.

The riders knew when the bullockies were coming. This meant mail, candy, newspapers, tobacco. Each division point and post which marked the end of each length of fence was a meeting place and post-office.

A spruce but taciturn, rather gloomy young man named Farrand from the next northern length, met Sam one day at the dividing post. One of the fence teams was due to return, bringing papers and mail. A hearty, red-faced Irishman named McManus, was the bullockie. He was usually half-snorted on wheat whiskey, but belligerently jovial. Sam liked him for his zest, and for the tall yarns he told around evening camp-fires.

Sam rather liked Farrand and wanted to be friends, but the other rider was reserved—not unfriendly, but simply aloof. He was the son of an English general, but had not inherited his father's abilities in Math. Farrand had been sent down from Sandhurst as a flunker, and had banished himself. He felt that his world had come to an end.

It was to be interesting enough to see how quickly the coming of this bullockie was to change the Englishman's viewpoint!

They saw the dust of the ox-wagon long before it arrived; and had a blazing fire, with tucker ready when McManus came. This time, however, they saw to their amazement that the Irishman was walking.

He had two blackboys with him, and six led camels followed the covered wagon. But the reason for walking was that three dustered female figures occupied the whole of the seat. Passengers—and women, in a land where white-skinned girls or women were almost non-existent!

In the flurry of greeting, campmaking, and hurried toilettes, Sam met a middle-aged, gloomy woman named Sara Peabody. She was the widow of a celebrated bushranger, who had been hanged with appropriate ceremony eighteen years before. Since that time she had been housekeeper for a rancher, Randall Smith. When his ranch failed. Smith took a place as fence-inspector, and Sara Peabody came with him to care for his motherless daughter, Claire.

Claire, now returning from three years of school at Perth, was a laughing, tomboyish sort, with freckles on her small nose, and ready comradeship in her clear blue eyes. Sam liked her at first sight, but found that there was always a queer constriction in his throat when he tried to talk to her She accepted him without constraint, and soon was jollying him—exactly as she talked with Farrand, or McManus, or Sara Peabody, for that matter.

The third duster girl was a young widow, just discarding mourning for an elderly husband. Her name was Elinor Mathes, and she was a coquettish brunette, friend of Claire, and ready for any new sensation she could find. This trip was an adventure, and on it she secretly meant to turn as many masculine heads as she was able.

Oddly enough, Farrand was entranced by her, and followed her around as though hypnotized. On the other hand. Elinor Mathes immediately showed a partiality for Sam Varney—and he could talk spiritedly to her because he knew much more about girls of her sort than he did about the Claire Smiths of the world. Sam never would be a victim of Elinor Mathes. She sensed the difficulty, and it put her on her mettle. Before that first meal was over, she had decided to add Sam to her string. But the man queerly enough showed only a sort of exasperation when she gave him all the opportunity in the world to fall in love.

After tucker there was the job for the men of raising the fence—the posts having been uprooted and the wire laid flat to allow the ox-wagon to reach the west side. The two younger women came out and talked, while Sara Peabody went about preparations for the night in the tent McManus pitched for them.

Then early goodnights, for the travellers were tired. McManus sat up smoking and talking to Ferrand and Sam for an hour after this. But the bullockie was not his jovial self. He had a bunion that ached, and he had heard tales about trouble all along the fence line. It seemed to be spreading further and further north, steadily.

"I'm told it's that divvil Trenholm that's behind most of it," the Irishman said. "It worries me, with these colleens along. Lave the blackfellows alone, an' they're peaceful entirely. Poke 'em up an' they may do anything a-tall!"

Sam learned that Elinor Mathes would visit Claire Smith and her father, Sara Peabody now returning from her luxurious three years as chaperon, to take up the duties of housekeeper again. Their place was far in the north, however. Sam Varney realized with a peculiar pang that in the ordinary nature of things he never would see Claire Smith again. She was the sort he genuinely liked. But, of course, with Trenholm still on the loose and his brother Tom still unsuccessful in the chase, Sam could not think of girls. That debt of $700 would take him a full year to clear, even if he spent nothing save odd silver for his own wants.

Next morning breakfast was early, then dust and swearing from McManus as the oxen were yoked, and the northward journey begun.

Claire came to Sam, waiting until Elinor's last dark-eyed coquetry had wasted itself. Then they shook hands. It was Claire who held to that clasp a second longer than necessary.

"Goodbye, Sam Varney," she said. "Come and see us when you're up our way."

"I'll come to see you!" he replied, since Elinor was getting into her seat in the wagon.

"That's what I meant, Sam Varney! she smiled—and then a moment later leaned out from her side seat to blow a kiss in his direction. Claire perhaps had her own style of coquetry, a little slower but far more effective with men like Sam.

Farrand did not say goodbye to Sam. The Englishman was riding north one hundred miles with the ox-wagon, to the end of this fence length. And for this stretch Farrand meant to improve every minute, which meant ceaseless attention to Elinor Mathes.

Chapter VIII

War Drums Thunder.

While Sam went about the routine of his work, his mind was filled with a desire to get transferred north. He liked Goelitz, and the inspector certainly had given Sam more than one unusual break.

Paxton Trenholm and presumably Tom Varney were up north somewhere now, however. And so was Claire Smith. McManus had intimated to the men alone that he thought Randall Smith a complete fool to bring women in to the lonely well cabin at a time like this. There would be days and nights when Smith himself could not get back to his headquarters, and the three women would be completely alone.

In past times this had been all right, but now with Trenholm fomenting raids, there was no guessing what might happen.

Oddly enough, Claire Smith thought a number of times, as she rode the slow ox-wagon north, that she would suggest Sam Varney's name to her father. It might be that Inspector Randall Smith could arrange unobtrusively to have the young rider transferred.

After saying farewell to Farrand, the ox-wagon entered the jurisdiction of Inspector Harris, and remained there for the next three hundred miles. After that dreary nine-day part of the journey was finished, traveling from dawn to dark of the summer days, they entered the three-length demesne of Inspector Burke. Claire's father was the next inspector to the north.

At the midway point of Burke's lengths, McManus the bullockie would turn back from the center of Australia and make his slow way back down the fence, gathering rabbit skins in bales and taking outgoing mail. One of the returning ox-wagons from the north would take Claire and the other two women the rest of the way home.

That was the plan, but it did not work out that way. Occasionally at sunset they heard a far-away whispering murmur of sound. It made the camels uneasy. Claire looked a little frightened, but said nothing to Elinor. These were the war drums of the aborigines.

The day before they reached the central well of Burke's sections—three hundred miles from home—the drums came nearer, and could not be blinked. McManus swore softly to himself, and Elinor asked wondering questions.

Up here the cameleers rode in pairs for protection. Several of them had been killed. There had been trouble three months earlier, but now it had returned with much greater seriousness. Afghan couriers came on swift meharis, but they spoke in gutturals only to the bullockie. Sara Peabody knew the signs, but she spent her time sitting straight and stiff. Her lips moved as she muttered prayers. Her refuge from everything was religion.

McManus went to Claire finally. "I'm worried, Ma'am," he said in a gruff undertone. "I wish you'd turn right about an' come back with me. Thim black Kimberley divvils from the northwest have been raidin'. The Parrabarras an' Aruntas ain't so bad, but the sivinfut Kimberleys! Tch! Then 'tis said the Parrabarras took a couple Kimberleys captive, an' ate 'em. That don't help none to speak of."

"Oh!" cried Claire, paling. Cannibalism, she knew, was impossible to suppress completely, but here it probably meant a long drawn out war between these two nomadic tribes, with white men suffering from the violence of both.

Something happened, however, to relieve McManus of responsibility, and make the remainder of the journey seem perfectly safe for the three women. A big stagecoach loaded with Government surveyors, and bristling with the barrels of ready rifles, caught up with McManus.

In the palaver that ensued, it developed that the surveyors would be only too glad to crowd together, some climbing to the top, in order to make room for three women—two of them young and pretty. Thus several days would be cut from the journey, and there would be plenty of defenders in case of attack. So it seemed.

Claire, Elinor and Sara Peabody made the change gladly. They learned the disturbing fact that the Government, valuing the line of protective fence more just at this time than it valued the completion of railway survey, had ordered every available man over to help defend the Smith and Doremus sections—Doremus being inspector of the northernmost division. It was thought that Paxton Trenholm had been stirring up the black nomads to war between themselves, and also to make attacks upon the fence and its defenders—

The horse-drawn stagecoach made much faster time—and necessarily, since cans of water had to be crowded on to supply man and beast for the full hundred miles between each two artesian bores. The coach was so crowded that everyone was uncomfortable, yet it seemed safe. They heard the drums fitfully, but there was nothing like a continuous booming of them. The aborigines really were few in number, though they travelled over vast distances, and might be a menace anywhere at any time.

It was the next to last day of the journey for Claire, when the attack came without warning. All of a sudden, as they passed through a ten-foot thicket of wattle, hideous yells sounded and a shower of spears flew. Two of the horses went down badly wounded, and the others, transfixed less seriously, snorted, squealed and thrashed about in a frenzy of fear.

The driver of the coach leaned side-wise, and fell off to the ground. The blade of a darrah-wood boomerang had crunched into his skull like a hatchet-blade into a pumpkin. The crazed horses, trying to bolt from the dying bodies of their companions, tipped over the stage. Terror-stricken men spilled out, clutching weapons but unable to get clear of the wreckage in time to use them speedily enough.

A dozen ochre-painted blacks sprinted forward to the massacre, shrieking their blood-madness. They swung stone waddies, stabbed with knives of volcanic glass. And so swiftly did it all happen that three of the surveying party went down with riven skulls before any one of the defenders could get clear of the debris and fire a single aimed shot.

But then came sudden change. Three men backed, crouching, pumping lead from hot rifles. Then came the flatter thunder of short-arms. It was a fury of extermination! Six, eight, ten of the blackfellows went down almost at once. The remaining ones saw and tried to flee, but too late. The revolver slugs cut them down without mercy. In less than fifteen seconds the entire fight was finished, and the scrub was a shambles.

Claire Smith had been flung out through the open door. Sara Peabody fell on top of her—and that saved Claire's life. A waddy stroke killed the elder woman, who had not even seen the black murderer making for her.

Inside the smashed coach they found the senseless Elinor Mathes. Outside of bruises—and a hair-raising adventure—she had not suffered seriously. But it would take several days before she would get over shivering.

They fixed up a rude drag, out of parts of the stagecoach. On it rode Claire and Elinor, while the surviving men walked alongside. Thus they came north, and were met unexpectedly by Inspector Randall Smith himself, and two of his cameleers.

Then they were safe enough, though no one felt like wasting time in getting back to the well cabin.

From two miles distant on a small, wooded knoll, a black-bearded giant white man had watched the destruction of the coach, and the final defeat of the black raiders. Now a snarl burst from Paxton Trenholm. He snapped together the brass telescope, and thrust it back into leather case.

"We ride another fifty miles north!" he rasped. "Bring the camels! They're not through with me yet!"

His black bodyservant and the three squat Malays ran immediately for the meharis.

Chapter IX

Black Fires.

Inspector Goelitz had refused Sam Varney's first overtures toward a transfer north, but ten days later news broke which changed everything. Sam did not hear until the end of the week, when Goelitz, with Farrand and a bearded jackaroo named Corbie, rode into his lonely camp to tell the ominous tale of what had happened in the north. Goelitz was to go with his experienced men. The supply base at Murriguddury would send men to take over temporarily. Corbie, a loose-witted drifter, was the first of these.

"Trenholm's blacks have stormed the wire! Attacked a stagecoach with three white women in it! Killed surveyors!" bellowed Corbie, who seemingly could not wait for the recital of his superior. "Blue-blazin' hell's to pay!"

"Claire Smith!" ejaculated Sam. "Was she—"

"Not hurt," said Goelitz. "Now you shut up, Corbie. He's going to take your place for now, Sam. The whole upper third of the wire is threatened. You, I and Farrand are going to ride night and day till we get there! Get your guns, ammunition and swag. Hurry!"

Five minutes later they left without ceremony. Riding all day, resting only a brief hour of the night to keep their camels going, they pressed north. Four days passed. On the northernmost section of Harris's part of the fence they found this inspector and all his cameleers working hard on an immense repair. Blackfellows had cut and carried away over two hundred yards of the posts and wire!

"You can't tell me my Parrabarras ever did this on their own!" snorted Harris, a belligerent, stocky man of middle height, with bushy reddish mustaches. "That black-whiskered fiend Trenholm is behind it. He sent a whole

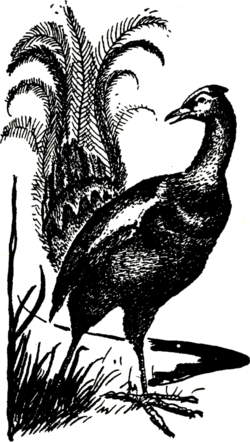

Emu

damn village to tear down this fence while I was thirty miles north. They killed Hank Jasper, and then put a spear through Ballinger's leg. Ballinger has the pack of rabbit hounds up here, you know."

The danger from rabbits was great, with so long a stretch of wire down. Goelitz, Farrand and Sam lent a hand in stretching the new wire. And while they were at it, back in the scrub sounded the whirring whine of many bull-roarers!

"I only hope Trenholm's with 'em when they come!" said Sam Varney grimly.

"No hope. He just eggs 'em on to raid, then sits back and watches the trouble. Crazy as a bedbug, of course."

This time there was no thought of allowing any work of destruction. The armed men met the gins, when they came from corroborree, and fired a volley over their heads. Disappointed in their hope of lifting another great length of wire, they fled with wailing cries.

But the skeleton-striped blackfellows, when they came, evidently had been fired with Trenholm's frenzy to a point where the threat of guns and determined white men could not scare. Howling, flourishing their waddies, spears, and hurling boomerangs, they swarmed to attack the whites between them and the wire.

The latter, just finished with the aduous fence repair, were merciless. The repeating rifles and small arms kept thundering, and fully twenty-five of the attackers died without ever getting close enough to kill a single white. Several of the fence men had minor spear wounds, and one had been knocked senseless by a glancing boomerang. But that was all. The black survivors finally realized that it was no use, and fled.

"That's all!" cried Inspector Harris. "Lord, aren't they gluttons for punishment!"

"Well, we'll press right along then," said Goelitz. "I think you've got this situation under control now."

As Sam rode his camel northward, however, a word of Harris's had started a train of speculations in his mind—golden speculations, tied up with dim, wondering thoughts of a girl who had freckles on her nose.

Gluttons! The reward for a suggestion which would end the rabbit plague in Australia! Claire Smith!

Sam had recalled with a thrill, tales told by one of his uncles who had been in the Klondike from '98 to 1901. The uncle had brought back little gold, but one of the stories he told now seemed to Sam extremely pertinent. It concerned a little animal of the north country which went around killing rabbits for the sheer fun of it!

This was the Canadian glutton—or wolverene, as some named it! Why should not Australia import a number of these small but ferocious killers, and let them loose to murder rabbits?

The very first chance he got, some days later, Sam put this idea in form of a letter, and sent it south by Afghan courier. Like all contestants for prizes the world over, then he dreamed of what he meant to do with $150,000 and five square miles of land. Naturally enough, most of those dreams had something to do with a girl who had blue eyes and freckles on her nose.

The next day saw a distinct change in the vegetation, as they pressed on toward the sections of Smith and Doremus. The mulga scrub thinned out and vanished. Its place was taken by beefwood, baobabs and kashew trees, and over the rolling plain small bolsons of kangaroo grass made the feeding of the camels easier.

Three more days, and they entered the section of Inspector Randall Smith. Goelitz kept scanning the northward horizon, and a frown corrugated his brows.

"Don't like it!" he said half to himself. "We haven't met a courier or a fence-rider—anybody!"

"There's a war on," Sam said, concealing his inward apprehension for Claire Smith and the girl, Elinor, who had gone north with her. "Prob'ly there're all up helping Doremus with the top section."

"The loot would look better here. Smith has the best house on the fence. Then—there's the women," said Goelitz grimly. Without more words the three men urged their camels to a shambling run. The beasts were nearing the point of complete exhaustion from their grueling trip, and the riders themselves were not much better off.

Nothing appeared that day. Next afternoon they reached the artesian well on the lowest length of Smith's section. Here stood the corrugated iron shack, iron water tank, windmill and pumphouse, and nothing else. The door of the shack sagged open, half-broken from its hinges. They knew the story before they reached the shack.

"Looted!" cried Farrand, who was first to dismount and take a look inside. The shack had been stripped of everything. Even the iron cots were gone.

"There were two riders here," said Goelitz, sadness in his eyes. "Let's shove along. It may be still worse up above."

Sam's face was drawn and stern. If Paxton Trenholm really was behind all these outrages, where could Tom Varney have gone? On a good camel, with the bushranger only a short way ahead, he must have caught up with the outlaw band long since.

The answer seemed plain. Tom had met Trenholm, and failed. It was all up to Sam now to uphold the honor of his family.

Progress now had diminished in heartbreaking fashion. The camels were ready to drop. Food had run out. There was no chance to hunt, except now and then to take snapshots with rifles at the small but edible "Nor'west parrots," which were a screeching nuisance everywhere. There were few rabbits in the traps of the fence, and in this hot climate the flesh of these stringy jacks was too strong-flavored to stomach.

Then on the second morning, as they were trying to flog Farrand's camel into rising to its feet—instead of lying there and moaning until it starved to death—all of them heard faint thunder of rifle firing ahead of them in the north. They mounted somehow, and forced the staggering, exhausted beasts onward.

Unshaven, hungry, in need of sleep, all three men were in a savagely worried frame of mind. And now appeared a terrifying discovery. Far ahead against the horizon, a column of thick, black smoke arose. At the height of perhaps one hundred fifty feet it mushroomed in a threatening club like the head of a waddy!

"Smith's house!" cried Goelitz bitterly. "Those poor women! It can't be anything but the house. That's built of darrah wood—pitchy. That's why the smoke is so black."

"Claire Smith!" whispered Sam to himself. His face had blanched beneath the dirt and tan. This was what they had feared. Yet the arrogant optimism of youth had said all along to the rider that this thing might happen to others, but not to him. Not to the girl he loved! Oh yes, it might not be love. He didn't really know. But that would be something to figure when and if—

The inspector's guess was proved certainty as they drove the gasping, tottering camels to the limit—and beyond. Farrand's mount suddenly collapsed under him, but he sprang free.

"Keep going!" he cried sharply, tugging at the rifle in the boot. "I'll be with you!"

Sam and Goelitz nodded, taut-lipped. They now could see the rolling billows of black smoke rising from the burning house. And now appeared an evil eye of red in the midst of the black.

Then the inspector shouted, reining up and holding one hand aloft. His camel immediately went to its knees with a stifled groan, then fell over. Goelitz leapt dear, running to where a dead body lay half-slumped, halfhung on the fence.

The dead man was undersized, stocky, brown of skin. His flat countenance and high cheekbones bespoke the Malay. He had been shot between the narrow eyes.

"Looks like one of Trenholm's gang!" shouted Sam. "Come on!"

He and Goelitz dashed through the aisles of a compact grape arbor, then across a small, irrigated truck garden near the artesian well. But both men knew at heart they were too late.

"No use at the house. Roof's fallen in!" shouted Sam. He shielded his face from the heat and circled.

Suffocating fumes swept at them from the blood-red, pitchy fire, blotting out their sight of one another. And then came a shout of discovery in Farrand's voice. He had dog-trotted after them. Reaching the far edge of the vineyard he had stumbled upon two headless corpses, and with them the body of a third man, unconscious but still breathing. It was patent, however, that the poor fellow could not live.

"Three cameleers!" gulped Goelitz, and swore savagely. "There's the pile of blackfellows they got before they cashed in! This chap—I don't know him—well, he's gone."

"Where are the women? The three girls?" cried Sam, beside himself with horror.

No present answer to that. In another angle of the grape arbor the searchers came upon all that was left of Inspector Randall Smith. Like the cameleers, he had fired every cartridge he carried, then died in hand-to-hand conflict, taking no less than six blacks with him—not counting those who doubtless fell at longer range.

One of Smith's arms had been chopped off just below the shoulder, and a waddy had smashed his skull to the bridge of his nose. They had stripped the body of clothing.

Later the bodies of two more men would be discovered in the cooling ashes of the house. But for now one thought and one only gripped Sam Varney.

"I'm going after her—then!" he told Goelitz. "I've tracked cows that were lost. Mebbe I can do something here. You—well, you get in touch with the police if you can."

"All right, Sam," said Goelitz soberly, taking no offense at being ordered about by his agonized subordinate. "God go with you!"

"I'll need a thousand devils if I find Trenholm!" grated Sam.

Chapter X

Answer to a Widow's Prayer.

Sam went on foot, travelling out west into the scrub, then circling. He came upon traces of two parties of blacks. No camel tracks. No sign of white woman's shoes.

"Mebbe only blacks were there—and they took her away!" breathed Sam. "Trenholm 'd be sitting back somewheres—like a big, black spider—"

Forced to choose, he took the second trail, which seemed to have been made by a party of fifteen or more blackfellows. The distances between footprints were enormous. Sam shuddered. He had glimpsed one of these Kimberley Lake blacks on two occasions—the times he had seen Paxton Trenholm with his bodyservant. The tracks made it almost certain these were not Parrabarras or Aruntas, who were of lesser stature. Many of the gaunt, somber-visaged Kimberleys were said to be seven feet tall—the tallest men of any race on the face of the earth.

In half an hour, though, he reached heavy thickets, where twigs and heavier branches lay springy in the leaf mould underfoot. Here the trail petered out, though evidently still bound in the same general direction.

Sam plugged on, going now in long, slanting zigzags first to left, then to right. He had the luck to cut the trail again, but now darkness was coming. He resolved to keep going, trusting in the coming of an early full moon. Chances were slender indeed, but he felt he had to give every one to the women caught by these primitive devils.

Moonrise found him still going. He stopped a few seconds every now and then, listening, hoping to hear the sounds of a native camp or village. If that were ahead of him, and the women captives there, Sam knew he would have the only advantage a lone white man could have. These superstitious aborigines never ventured out at night, peopling the dark with blood-thirsty bunyips and all other manner of man-eating devils.

Two more hours, three, passed slowly by—with fatigue gradually dulling the senses of the plodding man. Then suddenly he came to himself, falling! He had gone sound asleep on his feet!

He was forced to give up for the time being, make the best of it. He lay down, and instantly was gripped by the dreamless sleep of exhaustion.

Duck-billed platypus

While he slept forces he did not suspect fought to give him a chance. The indefatigable police had been warned the previous day, and four detachments had closed in, hoping against hope to trap the wily bushranger Trenholm, who had caused this uprising, as well as punish the murderous blackfellows.

And the police had succeeded in one thing, at least. They had turned back two forces of blacks, kept them moving through the night. Even now one of them was approaching the sleeping Sam Varney.

The jar of distant shots awoke Sam with a start. It was still bright moonlight, and he leapt up, dazed for a moment to find himself in the jungle thickets.

He came to his senses not a second too soon. Coming toward him through the thicket, hurrying like gaunt black specters of silence, came a scattered line of blackfellows spaced from one another like skirmishers.

With a yell of surprise, Sam dodged a spear as one of the black phantoms rushed at him and hurled a death shaft. A second later that aborigine sprawled on his face, one of Sam's rifle bullets through his bony chest.

Sam found himself facing three more—one of whom carried a limp, unconscious bundle in his arms. A white woman! Of course it had to be Claire. Sam forgot completely that there had been two others in that moment of flying spear and spouting lead.

Down went two of the blacks. And on both sides others yelled, probably thinking they had been trapped by more police. They fled at top speed, paying no attention to Sam, fortunately.

The gaunt Kimberley now flung aside the girl's body, and came for Sam with waddy swinging. Sam's rifle clicked—a dud cartridge, or else it had gone empty before he realized!

The stone waddy whished sidewise at his knees—the cunning stroke which cripples and fells an enemy, leaving him an easy victim for further attack.

Sam shouted, as he snatched desperately at his revolver. He leapt high, as a schoolgirl leaps over a skipping rope. And the waddy knocked away one of his heels, but did not touch flesh or bone!

As he alighted, and before the terrible club could be swung a second time, Sam shot once, twice, pointblank into the torso of the black. The aborigine bellowed, folded up and sprawled, twitching. It ceased. He was dead. Crouching, expecting more enemies, Sam stared about in the thicket. Nothing.

He was alone save for the girl he had rescued, there on the ground. She moved as he ran to her side, and lifted her face.

It was the coquette, the widow Elinor Mathes!