Goody Two-Shoes (1888)

GOODY TWO-SHOES.

FARMER MEANWELL was at one time a very rich man. He owned large fields, and had fine flocks of sheep, and plenty of money. But all at once his good fortune seemed to desert him. Year after year his crops failed, his sheep died off, and he was obliged to borrow money to pay his rent and the wages of those who worked on the farm.

At last he had to sell his farm, but even this did not bring him in money enough to pay his debts, and he was worse off than ever.

Among those who had lent money to Farmer Meanwell were Sir Thomas Gripe, and a Farmer named Graspall.

Sir Thomas was a very rich man indeed, and Farmer Graspall had more money than he could possibly use. But they were both very greedy and covetous, and particularly hard on those who owed them anything. Farmer Graspall abused Farmer Meanwell and called him all sorts of dreadful names; but the rich Sir Thomas Gripe was more cruel still, and wanted the poor debtor shut up in jail.

So poor Farmer Meanwell had to hasten from the place where he had lived for so many years, in order to get out of the way of these greedy men.

He went to the next village, taking his wife and his two little children with him. But though he was free from Gripe and Graspall she was not free from trouble and care.

He soon fell ill, and when he found himself unable to get food and clothes for his family, he grew worse and worse and soon died.

His wife could not bear the loss of her husband, whom she loved so dearly, and in a few days she was dead.

The two orphan children seemed to be left entirely alone in the world, with no one to look after them, or care for them, but their Heavenly Father.

They trotted around hand in hand, and the poorer they became the more they clung to each other. Poor, ragged, and hungry enough they were!

Tommy had two shoes, but Margery went barefoot. They had nothing to eat but the berries that grew in the woods, and the scraps they could get from the poor people in the village, and at night they slept in barns or under hay-stacks.

Their rich relations were too proud to notice them. But Mr. Smith, the clergyman of the village where the children were born, was not that sort of a man. A rich relation came to visit him—a kind-hearted gentleman—and the clergyman told him all about Tommy and Margery. The kind gentleman pitied them, and ordered Margery a pair of shoes and gave Mr. Smith money to buy her some clothes, which she needed sadly. As for Tommy he said he would take him off to sea with him and make him a sailor. After a few days, the gentleman said he must go to London and would take Tommy with him, and sad was the parting between the two children.

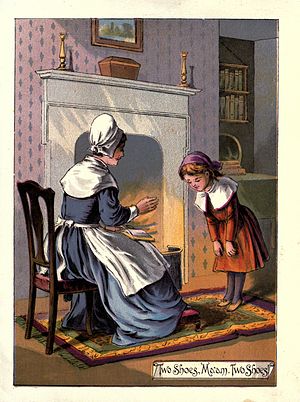

Poor Margery was very lonely indeed, without her brother, and might have cried herself sick but for the new shoes that were brought home to her.

They turned her thoughts from her grief; and as soon as

Little Margery had seen how good and wise Mr. Smith was, and thought it was because of his great learning; and she wanted, above all things, to learn to read. At last she made up her mind to ask Mr. Smith to teach her when he had a moment to spare. He readily agreed to do this, and Margery read to him an hour every day, and spent much time with her books.

Then she laid out a plan for teaching others more ignorant than herself. She cut out of thin pieces of wood ten sets of large and small letters of the alphabet, and carried these with her when she went from house to house. When she came to Billy Wilson's she threw down the letters all in a heap, and Billy picked them out and sorted them in lines, thus:

A B C D E F G H I J K,

a b e d e f g h i j k,

and so on until all the letters were in their right places.

From there Goody Two Shoes trotted off to another cottage, and here were several children waiting for her. As soon as the little girl came in they all crowded around her, and were eager to begin their lessons at once.

Then she threw the letters down and said to the boy next her, "What did you have for dinner to-day?" "Bread," answered the little boy. "Well, put down the first letter," said Goody Two Shoes. Then he put down B, and the next child R, and the next E, and the next A, and the next D, and there was the wole word—BREAD. "What did you have for dinner, Polly Driggs?"

"Apple-pie," said Polly; upon which she laid down the first letter, A, and the next put down a P, and the next another P, and so on until the words Apple and Pie were united, and stood thus: APPLE PIE.

Now it happened one evening that Goody Two Shoes was going home rather late. She had made a longer round than usual, and everybody had kept her waiting, so that night came on before her day's work was done. Right glad was she to set out for her own home, and she walked along contentedly through the fields, and lanes, and roads, enjoying the quiet evening. The evening was not cool, however, but close and sultry, and betokened a storm. Presently a drop fell on Goody's face. What should she do? If she did not make haste she would soon be wet to the skin.

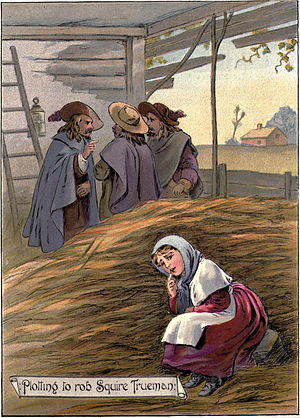

Fortunately there was an old barn down the road, in which she could find shelter, and Goody Two Shoes gathered her skirts about her and took to her heels, and ran as if somebody was after her. The owner of the barn had died lately, and the property was to be sold, and there was a lot of loose hay on the floor which had not yet been taken away.

Goody Two Shoes cuddled down in the soft hay, glad of a chance to rest her weary limbs, and quite out of breath with her long run; and just then down rattled the rain, the thunder roared, the lightning flashed, and the old barn trembled, and so did Goody Two Shoes.

She had not been there long before she heard footsteps, and three men came into the barn for shelter. The hay was piled up between her and them, so that they could not see her, and, thinking they were alone, they spoke quite loudly.

He was at dinner with some friends, and any one else but Goody would have found it difficult to gain admission to him. But she was well known to the servants, and was so kind and obliging, that even the big fat butler could not refuse to do her bidding, and went and told the squire that Goody Two Shoes wished very much to see him.

So the squire asked his friends to excuse him for a moment, and came out and said, "Well, Goody Two Shoes, my good girl, what is it?" "Oh, sir," she replied, "if you do not take care you will be robbed and murdered this very night!"

Then she told all she had heard the men say while she was in the barn.

The squire saw there was not a moment to lose, so he went back and told his friends the news he had heard. They all said they would stay and help him take the thieves. So the lights were put out, to make it appear as if all the people in the house were in bed, and servants and all kept a close watch both inside and outside.

Sure enough, at about one o'clock in the morning the three men came creeping, creeping up to the house with a dark lantern, and the tools to break in with. Before they were aware, six men sprang out on them, and held them fast. The thieves struggled in vain to get away. They were locked in an out-house until daylight, when a cart came and took them off to jail.

They were afterward sent out of the country, where they had to work in chains on the roads; and it is said that one of them behaved so well that he was pardoned, and went to live at Australia, where he became a rich man.

The other two went from bad to worse, and it is likely that they came to some dreadful end. For sin never goes unpunished.

But to return to Goody Two Shoes. One day as she was walking through the village she saw some wicked boys with a raven, at which they were going to throw stones. To stop this cruel sport she gave the boys a penny for the raven, and brought the bird home with her. She gave him the name of "Ralph," and he proved to be a very clever creature indeed. She taught him to spell, and to read, and he was so fond of playing with the large letters, that the children called them "Ralph's Alphabet."

Some days after Goody had met with the raven, she was passing through a field, when she saw some naughty boys who had taken a pigeon, and tied a string to its legs in order to let it fly and draw it back again when they pleased.

Goody could not bear to see anything tortured like that, so she bought the pigeon from the boys and taught him how to spell and read. But he could not talk. And as Ralph, the raven, took the large letters, Peter, the pigeon, took care of the small ones.

Mrs. Williams, who lived in Margery's village, kept school, and taught little ones their A B C's. She was now old and feeble, and wanted to give up this important trust.

So Margery Meanwell was now a schoolmistress, and a capital one she made. The children all loved her, for she was never weary of making plans for their happiness.

The room in which she taught was large and lofty, and there was plenty of fresh air in it; and as she knew that children liked to move about, she placed her sets of letters all round the school, so that every one was obliged to get up to find a letter, or spell a word, when it came their turn.

This exercise not only kept the children in good health, but fixed the letters firmly in their minds.

The neighbors were very good to her, and one of them made her a present of a little skylark, whose early morning song told the lazy boys and girls that it was time they were out of bed.

Some time after this a poor lamb lost its dam, and the farmer being about to kill it, she bought it of him, and brought it home to play with the children.

Soon after this a present was made to Miss Margery of a dog, and as he was always in good humor, and always jumping about, the children gave him the name of Jumper. It was his duty to guard the door, and no one could go out or come in without leave from his mistress.

Margery was so wise and good that some foolish people accused her of being a witch, and she was taken to court and tried before the judge. She soon proved that she was a most sensible woman, and Sir Charles Jones was so pleased with her, that he offered her a large sum of money to take care of his family, and educate his daughter. At first she refused, but afterwards went and behaved so well, and was so kind and tender, that Sir Charles would not permit her to leave the house, and soon after made her an offer of marriage.

The neighbors came in crowds to the wedding, and all were glad that one who had been such a good girl, and had grown up such a good woman, was to become a grand lady.

Just as the clergyman had opened his book, a gentleman, richly dressed, ran into the church and cried, "Stop! stop!"

Great alarm was felt, especially by the bride and groom, with whom he said he wished to speak privately.

Sir Charles stood motionless with surprise, and the bride fainted away in the stranger's arms. For this richly-dressed gentleman turned out to be little Tommy Meanwell, who had just come from sea, where he had made a large fortune.

Sir Charles and Lady Jones lived very happily together, and the great lady did not forget the children, but was just as good to them as she had always been. She was also kind and good to the poor, and the sick, and a friend to all who were in distress. Her life was a great blessing, and her death the greatest calamity that ever took place in the neighborhood where she lived, and was known as

![]()

This work was published before January 1, 1929, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse