Health and beauty by Caplin/Chapter IV

CHAPTER IV.

CLOTHING FROM THE AGE OF TWELVE TO EIGHTEEN YEARS.

Having now discussed the more important matters relative to childhood, we may advance another stage with our subject, and take into consideration a few of the many important matters which pertain to the period of adolescence, which is the transition-state from childhood to womanhood. During the whole of this time all the vital functions are active in preparing for the growth and higher development of the body, whilst at the same time the bones are soft, the cartilages and ligatures yielding and easily bent, and any perversion of the growth which may now take place is likely to leave its impression on the frame for life.

During its progress through this equivocal state there is one thing above all others that youth requires, and that is absolute freedom. The exercises should be sufficient to bring all the organs of the body into action, and yet not so severe as to exhaust the energies or cause an undue development of some particular members.

Talking—not screaming—in the open air should be encouraged, that the lungs may be thoroughly inflated with fresh air; nor can this absolute freedom and proper healthy exercise ever take place unless the clothing be properly adapted to the undulating outline of the female form, so as to allow it to fall with ease into those elegant curves on which physical beauty depends. When these things are neglected, the young lady becomes dull and lifeless, the gait is inelegant, and the contour of the figure deranged. Parents and teachers should bear in mind that to train a lady it is not necessary that she should be an invalid, and good bodily health will always be found favourable to every kind of intellectual culture.

Everyone is aware that by proper education the intellectual faculties may be improved; but there are few who have ever reflected on the fact that the ugly might have been made handsome, and the deformed comely, if the body had received the same amount of culture which has been bestowed upon the mind. This, however, is the lowest aspect of physical training; for as the body is the organism through which the mind is manifested, the perfecting of that organism gives free scope to the exercise of the soul, and hence lays the basis of a higher life; but as this is an important subject we must make it plain.

Life is carried on by certain great functions, which we call Respiration, Digestion, Circulation, and Secretion, all of which proceed under the impulse of the involuntary nerves; all of them are, however, dependent upon the voluntary nerves and muscles for their proper operation. Breathing requires exercise, change of air and position; digestion demands the procuring and preparing of the food; circulation can only be brisk when the body is in motion: and all these motions are necessary to a proper and healthy secretion of the fluids and solids taken into the stomach. We may therefore say that life is dependent upon voluntary as well as involuntary motion for its existence, and above all it may be affirmed, that a healthy and sound body is never seen, unless there has been proper daily exercise. For, as every function that we have named must be maintained in order that there may be a state of perfect health, so also the whole congeries of organs must be exercised together, in order that there may be nothing superfluous, and nothing wanting, in the entire fabric.

If we take each part separately we shall arrive at the same result as if we speak of the whole together. No organ is of greater importance to life than the lungs; and hence it is necessary not only to breathe a pure atmosphere, but also that we take in enough of it at every respiration to inflate the whole chest. The lungs may be said to commence with the soft lining of the trachea, and to extend in two huge lobes down into the chest; and so thin and delicate is the substance of which they are composed, that enough of it is folded into a single thorax to cover one hundred and sixty square yards. This great extent of surface has been given for the purpose of multiplying the air-cells, of which there are about six hundred millions, and their office is to take the oxygen from the atmosphere, vitalize the blood, and send it back to the heart, and from thence to every part of the body. Now, when the lungs are contracted by a compressed chest, two evils naturally result: in the first place, there is a low and feeble circulation, which is sure to induce weakness, languor, or idleness, for the brain and other organs are unable to fulfil their functions for the want of that stimulus which is essential to bodily and mental activity; but there is a second and more dangerous evil than this. The compression of the chest brings the thin membrane of the lungs into contact, and upon the slightest inflammation suppuration naturally takes place, and hence pulmonary consumption is established. Writers upon phthisis are at present speculating upon the cause of the frequency of this malady, and some of them find it in the moist condition of our atmosphere, others in the supposed hereditary scrofulous state of the blood; but if those gentlemen will only look at, the common practice of diminishing the capacity of the chest by stooping, or the shortening of the spine, consequent, perhaps, upon ill-adapted clothing, they will find in this a much more frequent cause of premature death from diseased lungs than any other that might be named. Indeed, the full development of the capacity of the chest, is a matter of so much importance, that where this is not attended to, the subject may be said to be constantly liable to this grievous malady.

It is a sad reflection that this tendency to a contracted chest is more common amongst the middle and higher classes, in whose children we ought to witness the most perfect physical organizations, than it is amongst the poor. Children who are allowed to jump, play, and skip, or roll on the floor or flags, are much more likely to have robust bodily health, than those who are always "taken care of." The enemy of the poor child is neglect, that of the rich inactivity. The only exception to this statement will be found in the cases of those mechanics and artisans who are obliged to lean forward over their work, and whose hands are taught, by constantly practising one thing, to strike curves like compasses; but one glance at that pale and haggard face is enough to convince anyone that nature takes ample vengeance for the crushing to which the vital organs are daily subjected. The poor child who is cooped up in the nursery and deprived of that freedom of action which is essential to the growth of every organised being, can never be properly developed. The kitten plays and the lamb bounds and skips, but the "good child" is expected to be quiet, and then it is made a matter of wonder that it is sickly or deformed, when so much care has been taken of it.

It was Swedenborg, we believe, who was the first amongst the physiologists to show that the whole body breathed, and that, as a natural consequence, every organ respired in unison with the lungs; by carrying out this idea to the brain, its moral importance may be at once seen, for unless the lungs be properly inflated, and the respiration deep and perfect, no earnest and noble thought and generous and energetic action is possible. In cultivating the body, therefore, we are elevating the mind also, and are rendering a life great and admirable which would otherwise be dull, useless, and contemptible.

Our space forbids that we should discuss this question in reference to every organ of the body; but if there be anyone part more than another which requires constant exercise, it is the skin. This membrane, which envelopes the whole body, performs functions of the highest physical and moral importance. If it be in any way obstructed, the internal organs are oppressed, and hence fever or inflammation results; and when there is any cutaneous eruption, the malady is not only prejudicial to health, but is also attended with an irritable temper, and too often with bad moral results. Now exercise, proper daily ablutions, friction, plenty of pure air, and the constant motion of the muscles, are all necessary for the purpose of keeping the skin in a perfectly healthy condition.

It will be perceived from these remarks, that we fix a very high standard for the development of the body. Ignorance and idleness are the sole causes of so much deformity and disease as it is our fate to witness; and hence it only requires the proper adaptation of the means to ensure a healthy, vigorous, and beautiful physical organization. It is not simply the original form so much as the culture, which gives beauty to humanity. The higher beauty, the beauty of soul, is never seen—no, not in the face of a Georgian, unless education has given its aroma to the original grace of the flower.

How, then, it will be asked, is this consummation to be attained? for all exercise is not alike beneficial; and, in addition to this, we do not want a partial development. Ladies especially do not need the muscular energy of the mechanic. They do not indeed require to be made masculine at all. Our reply is, that, as we have two objects to accomplish, namely, the full and perfect culture of the well-formed, and the restoration of such as are only imperfectly developed, we must adapt our means to the end proposed, and exercise the body upon itself, as is done in running, walking, and swimming, for those only who require this training; but in all cases where there is deformity, or only partial evil, the curative means must be adapted to the restoration of the imperfect organs.

The importance of commencing the physical training of the child at a very early age will be rightly esteemed by all, who consider how much it has to learn during the first two years of its life; for it is in this period that all things emerge from chaos, and become defined by the senses, and their form, size, shape, and colour noted. Now, all who are acquainted with physiology, know perfectly well that the mind cannot be properly unfolded unless the organism through which it is manifested be in a healthy condition, so as to be enabled to register the impressions made upon it by external circumstances. "Forms arise before the eye, and sink again; sounds thrill upon the ear and vanish; the infant begins to give the bounds to forms, and to catch the sounds that float upon the air, and. discriminate between them. * * * By innumerable attempts which comprise the first exercise of the limbs, the child learns to distinguish distance; thousands of experiments bring the gradual knowledge of surrounding things; and this, by the aid that is tendered to it by the nurse or mother, forms the first portion of the child's education."*[1] Now, to aid this, the whole organic structure must be taken into consideration—the limbs, senses, lungs, stomach, and above all, the condition of the spine; for each and all of those organs must be in a perfectly healthy state, and must perform their functions properly, or the brain will not be in a condition to receive and retain the impressions transmitted to it.

Nature is always beneficent, and is ever striving to correct and amend the evils inflicted upon the body by the vicious habits which are almost universally indulged in. One portion of the community neglects the skin, others breathe impure air, others are in the daily habit of taking either too little or too much food and drink, or that which is deleterious. It is the almost universal practice to educate only one hand, to sleep constantly upon one side, stand upon one leg, or bend and keep the body in some awkward position. Hence, in a long experience I have never found one person physically perfect, and conclude, therefore, that nine hundred and ninety-nine of every thousand people that we meet with are imperfectly developed. Here there is work for the teacher:

Present Fashion.

Amongst the causes, however, which produce spinal deviations in young ladies there is none that is more general than improper clothing. Fashion has superseded utility to such an extent amongst the rich, that the limbs of the young are contracted by their dress; and amongst the poor a want of skill in the adaptation of the materials to the form of the body is so common that it is a rare thing indeed to see anyone who can be said to be properly clothed. We boast much, and we have reason to do so, of the superiority of the West over the East; but in the proper art of dressing, that is, in the adaptation of the materials worn to display the form and beauty of the body, we are far behind many of the rude nations of antiquity, and also of the partially civilised Asiatic races. Look at the figure on the opposite page, and then say if any dress can be more unnatural than the present costume.

The construction of the clothing, however, always a matter of the highest importance in every period of life, is more especially so during the time of its growth, and just before the body reaches maturity. Economy dictates the wearing of the clothes so long as they look well, and if they should become too small for the elder, that they should be passed on to the second and third, if need be, until they are worn out. The only objection to this is, that they may be said never to fit. It is true that our idea of the fitting or adaptation of clothes differs very much from that which is ordinarily prevalent. With us, it is necessary that they should not only look well, but they should also BE well suited to the requirements of the wearer. Now, it is well known that when the body ceases to grow the bones become fixed, and it is consequently more difficult to correct any deviation, or restore the figure to its normal state, after this period. It naturally follows, therefore, that the period of growth being that in which the body is more yielding, it is at that time more subject to deformity than at a later period of life. We must therefore insist that at this time there must be no cutting with strings or garters; no compression of the centre of the body by badly constructed corsets; no slipping off the clothes from the shoulders and resting on the arms; no contraction in any part of the whole costume, but absolute freedom of action for every organ and muscle.

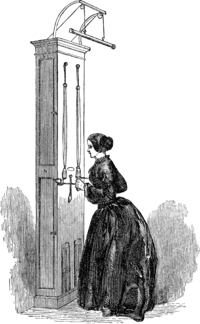

With so many commands not to do, the gentle reader will naturally ask what she is to do, in order that her charge may be healthy and acomplished. To this we reply, that she must always adapt both teaching, exercise, and discipline to the nature and constitution of the child, that is, to the especial requirements of that particular child to which she may have to direct attention. In the first place, the school seats must be so constructed as to afford support to the back whenever the pupil needs to recline backwards. The seat and back also should be covered with cloth, and stuffed, so as to render them comfortable, and the pupils be allowed to rest occasionally. The teacher must always bear in mind that her object is to make her pupils proficient, and she cannot do this except their studies be made delightful to them. When the tuition is irksome, it will always be shunned if possible, and hated when it cannot be avoided. It is possible, we know, to drill a human being into a routine of mechanical movements, mental as well as bodily; but this is not education in the sense in which we use the term. There is no drawing out of the higher faculties of the soul, and consequently no love of wisdom imparted under such a system: neither walking, however, nor any other exercise of the body upon itself, can ever give all the movements necessary to a young person for the perfecting of the frame; and it was this conviction which led Dr. Caplin to invent the vast number of mechanical contrivances which make up his magnificent gymnasium. There is one apparatus, however, which we should recommend as indispensable for a family, and that is the Pilaster. This simple machine, which is at once compact and ornamental, supplies the means for fifteen different exercises, enabling us to expand the chest, or strengthen by exercise any member of the body that needs our aid. Nor is it possible to do this without some adaptation of mechanical means; and the more perfect the means, the more complete will be the success.

That the reader may have a clear conception of our meaning, we introduce here a short description of this apparatus from the "Lady's Newspaper." Take the first illustration of its use as a chest-expander. (See Fig. 1.)

The expansion of the chest is one of the first things to be attended to, in any efforts to improve the bodily health. Now, the thorax is composed of the spine posteriorly, and of the sternum, or breast-bone and ribs laterally. The ribs incline downward with the spine, and hence, when we bend forward, the inclination is greater; and as a natural consequence, the capacity of the chest is diminished, and the ability to breathe freely suspended. To this we may attribute pallor, ill-health, and affections of the chest. All the bones are more or less under the command of the muscles, and in such a case as that which we are supposing, it is the weakness of the muscles of the back

Fig. I.—Chest Expander.

that has caused the deformity; and, as a natural consequence, the exercise of those muscles will restore their healthy action, and with it, the figure to its natural position.

As a general rule, one arm is stronger than the other, and requires a separate exercise to restore the equilibrium; and this we attain by moving the members in such a manner as shall act upon the part that needs our aid: We commence with the Bow Exercises.

Fig. 2.—Bow, or Archery Exercise.

This will bring into action all the muscles of the arm; but, in order to give the whole arm and shoulder full play, other exercises are requisite, especially those which appeal to the muscles of the back and lower extremities; for, as a general rule, it is not well to appeal to an isolated set of muscles only. In this case the rowing motion is desirable. (See Fig. 3.)

The sawing exercise is performed with the same handles as the rowing, the pupil only taking another position. The alternate pressure which this exercise causes upon the cartilages which separate the bones of the spine promotes its elasticity, and enables it to maintain the upright and natural position. (See Fig. 4.)The feet and ankles are exercised by another set of motions, which we denominate treading. (See Fig. 5.)

To promote the general heat of the blood, and increase the whole vital action, there is nothing that equals the jumping exercise. (See Fig. 6.)

These are some of the important exercises which are performed upon

Fig. 3.—Rowing Position.

the Pilaster; but this is only one of scores of similar contrivances which Dr. Caplin has adapted to every age, sex, or weakness. A patient study of the human frame has enabled him to interpret the dictates of Nature, and to assist her in her efforts to impart health, strength, grace, and beauty to the whole system. *[2]

Respecting the materials of which the clothing should be composed, we can only offer the most general observations, as this must depend in some measure upon the taste of the parents. The clothing should always be light and warm; the frock and under-garments moderately loose, but always adapted to the outline of the body, so as to form a perfect fit, and their weight sustained upon the shoulders. Flannel should be used, as, from its being a non-conductor of heat, it lessens the liability of taking cold; when, however, the skin is so susceptible as to render it painful to wear flannel, calico must be substituted. Drawers also should be worn,

Fig. 4.—Sawing Exercise.

to keep up the circulation in the lower extremities, and the feet be kept warm by the use of woollen stockings during the winter season. Wide elastic garters, such as those which we have invented, that do not obstruct the capillary circulation, should, be substituted for the old unyielding strings, and the boots should not be laced so tight as to stop the supply of blood to the feet, as it causes them to swell in summer, and increases the liability to chilblains in the winter. When these general rules are attended to, the clothing will be elegant, and always conducive to health.

It may perhaps be asked, why we have confined our observations almost entirely to girls; and whether boys are not also affected by deviations from the erect posture of a similar kind. In early life the same causes which affect the one operate also to the detriment of

Fig. 5.—Treading Position.

the other; and we accordingly find that boys are equally subject to poking of the head, roundness of the shoulders, contraction of the chest, and curvature of the spine, as girls, at that particular epoch. Boys' dresses at that period differ little from girls', and as we have shown that these evils are occasioned by a bad method of dressing, the same effects must be produced irrespective of sex. Mark, however, the difference of the subsequent clothing and exercise of the boy as compared with that of the girl. In the course of a few years he enjoys the superlative delight of adopting the clothes peculiar to his sex, and is accordingly released from the trammels he has been hitherto compelled to endure. His trousers fit closely over the hips, and are suspended by braces passing over the shoulders, and crossing on the back. His jacket and waistcoat are cut in such a manner that his arms can be allowed free and natural motion; no compression

Fig 6.—Jumping Position.

is made upon the chest, and he can therefore assume the erect position without any counteracting influence from the dress. When this change is made in the clothing, it will be found on careful admeasurement that the boy will immediately increase in height in a very perceptible manner, that his chest will become broader, his back narrower, his breathing less laborious, and his countenance redolent of health, in consequence of the improved circulation. His arms, too, instead of falling in front of the body, will hang rather backwards, his head become more erect, and he will experience a sensation of comfort to which he has hitherto been a stranger. A feeling of unpleasant stiffness may be complained of on his assuming this manly attitude, and this arises from the muscles of the chest and back being brought more into action, and also to the back part of the intervertebral cartilages having become thickened, from his long habit of stooping. We frequently hear a remark of the same kind made by ladies on being first placed perfectly erect; but this stiffness is invariably succeeded by a sensation of relief. Proud in the consciousness of his vigour, the boy now shows his enjoyment of it by a thousand antics; his pace becomes rapid, he runs without fatigue, and when in the playground exercises his chest by exhilarating though frequently discordant shouts. All this good is effected simply by the change from an improper to a judicious mode of clothing; and it will be at once seen that our views on the subject of female dress would, if properly carried out, produce precisely analogous results. *[3]

There is a mode of dressing boys which is calculated to perpetuate the stooping position contracted in infancy; but it is now, fortunately, falling into disuse. We mean the wearing of a little waistcoat, to which the trousers button in lieu of braces. Of course, by this, the trousers must be drawn up tightly in the front, and the pressure fall upon the back of the neck, thereby dragging the head and arms forward. Some years ago, I ordered a dress of this description for my own son, and when it was tried on, found that he stooped very much. I accordingly unbuttoned the front buttons which attached the trousers to the coat, and told him to stand upright, which he did, and I then perceived that a space was left of more than three inches between the garments, which had been taken at the expense of the thorax. I at once threw aside the waistcoat and adopted braces of my own invention, which have since been exhibited at the Crystal Palace, and which answered the purpose effectually, without impeding the freedom of the limbs. The same result has been experienced by all who have subsequently tried them, as they make up for want of power in the muscles of the back, and thereby assist in preserving the erect position.

|

|

figures of a boy.

The above figures present no exaggeration of the effects of the clothing which we have referred to. The sketches are taken from life, and represent the same child in two different dresses. No mere verbal description can add to the impression which those illustrations are sure to produce.

- ↑ * Woman's Educational Mission, p. 16.

- ↑ * A visit to the Royal Hygienic Gymnasium, 9, York Place, Portman Square, is respectfully solicited from all who desire further information on this matter.

- ↑ * Boys are, however, subject to an annoyance to which girls are comparatively strangers. The upper portion of the body is kept warm from the inordinate quantity of clothing, whilst the legs are left perfectly bare, and exposed to all the inclemency of the weather. I once had a beautiful boy brought by his mother into my room. Fascinated by the beauty of the dear child, I grasped his legs to shake them, as I believe most mothers would do, and was shocked to find them so blue and cold that he actually had no sensation there whatever. He wore a little bear-skin coat which kept the upper portions of the body at a temperature of 68° Fahrenheit, but, upon applying the thermometer to his dear little legs, it only indicated a heat of 42°. He looked ill, and had been taken to several medical men, who pronounced his liver out of order; but I thought that warm stockings might be useful, and accordingly recommended them, and in a few weeks had the satisfaction of hearing that the child's health was restored.