Highways and Byways in Sussex/Chapter 34

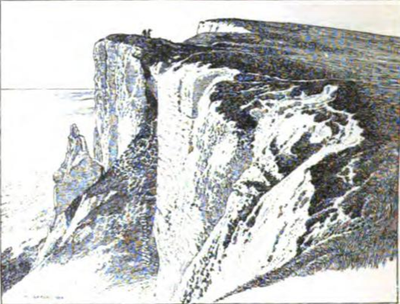

Beachy Head.

CHAPTER XXXIV

EASTBOURNE

Select Eastbourne. The "English Salvator Rosa"—Sops and Ale—Beau Chef—"The Breeze on Beachy Head"—Shakespeare and the Cliff—"To a Seamew"—The new lighthouse—Parson Darby and his cave—East Dean's bells—The Two Sisters—Friston's Selwyn monument—West Dean.

Eastbourne is the most select, or least democratic, of the Sussex watering places. Fashion does not resort thither as to Brighton in the season, but the crowds of excursionists that pour into Brighton and Hastings are comparatively unknown at Eastbourne; which is in a sense a private settlement, under the patronage of the Duke of Devonshire. Hastings is of the people; Brighton has a character almost continental; Eastbourne is select. Lawn tennis and golf are its staple products, one played on the very beautiful links behind the town hard by Compton Place, the residence of the Duke; the other in Devonshire Park. It is also an admirable town for horsemanship.

Eastbourne has had small share in public affairs, but in 1741 John Hamilton Mortimer, the painter, sometimes called the Salvator Rosa of England, was born there. From a memoir of him which Horsfield prints, I take passages: "Bred on the sea-coast, and amid a daring and rugged race of hereditary smugglers, it had pleased his young imagination to walk on the shore when the sea was agitated by storms—to seek out the most sequestered places among the woods and rocks, and frequently, and not without danger, to witness the intrepidity of the contraband adventurers, who, in spite of storms and armed excisemen, pursued their precarious trade at all hazards. In this way he had, from boyhood, become familiar with what amateurs of art call 'Salvator Rosa-looking scenes'; he loved to depict the sea chafing and foaming, and fit 'to swallow navigation up'—ships in peril, and pinnaces sinking—banditti plundering, or reposing in caverns—and all such situations as are familiar to pirates on water, and outlaws on land....

"Of his eccentricities while labouring under the delusion that he could not well be a genius without being unsober and wild, one specimen may suffice. He was employed by Lord Melbourne to paint a ceiling at his seat of Brocket Hall, Herts; and taking advantage of permission to angle in the fish-pond, he rose from a carousal at midnight, and seeking a net, and calling on an assistant painter for help, dragged the preserve, and left the whole fish gasping on the bank in rows. Nor was this the worst; when reproved mildly, and with smiles, by Lady Melbourne, he had the audacity to declare, that her beauty had so bewitched him that he knew not what he was about. To plunder the fish-pond and be impertinent to the lady was not the way to obtain patronage. The impudent painter collected his pencils together, and returned to London to enjoy his inelegant pleasures and ignoble company."

Horsfield states that "a custom far more honoured by the breach than the observance heretofore existed in the manor of Eastbourne; in compliance with which, after any lady, or respectable farmer or tradesman's wife, was delivered of a child, certain quantities of food and of beer were placed in a room adjacent to the sacred edifice; when, after the second lesson was concluded, the whole agricultural portion of the worshippers marched out of church, and devoured what was prepared for them. This was called Sops and Ale."

John Taylor the water Poet, whom we saw, at Goring, the prey of fleas and the Law, made another journey into the county between August 9th and September 3rd, 1653, and as was usual with him wrote about it in doggerel verse. At Eastbourne he found a brew called Eastbourne Rug:—

No cold can ever pierce his flesh or skin

Of him who is well lin'd with Rug within;

Rug is a lord beyond the Rules of Law,

It conquers hunger in a greedy maw,

And, in a word, of all drinks potable,

Rug is most puissant, potent, notable.

Rug was the Capital Commander there,

And his Lieutenant-General was strong beer.

Possibly it was in order to contest the supremacy of Rug (which one may ask for in Eastbourne to-day in vain) that Newhaven Tipper sprang into being.

The Martello towers, which Pitt built during the Napoleonic scare at the beginning of last century, begin at Eastbourne, where the cliffs cease, and continue along the coast into Kent. They were erected probably quite as much to assist in allaying public fear by a tangible and visible symbol of defence as from any idea that they would be a real service in the event of invasion. Many of them have now disappeared.

Eastbourne's glory is Beachy Head, the last of the Downs, which stop dead at the town and never reappear in Sussex again. The range takes a sudden turn to the south at Folkington, whence it rolls straight for the sea, Beachy Head being the ultimate eminence. (The name Beachy has, by the way, nothing to do with the beach: it is derived probably from the Normans' description—"beau chef.") About Beachy Head one has the South Downs in perfection: the best turf, the best prospect, the best loneliness, and the best air. Richard Jefferies, in his fine essay, "The Breeze on Beachy Head," has a rapturous word to say of this air (poor Jefferies, destined to do so much for the health of others and so little for his own!).—"But the glory of these glorious Downs is the breeze. The air in the valleys immediately beneath them is pure and pleasant; but the least climb, even a hundred feet, puts you on a plane with the atmosphere itself, uninterrupted by so much as the tree-tops. It is air without admixture. If it comes from the south, the waves refine it; if inland, the wheat and flowers and grass distil it. The great headland and the whole rib of the promontory is wind-swept and washed with air; the billows of the atmosphere roll over it.

"The sun searches out every crevice amongst the grass, nor is there the smallest fragment of surface which is not sweetened by air and light. Underneath the chalk itself is pure, and the turf thus washed by wind and rain, sun-dried and dew-scented, is a couch prepared with thyme to rest on. Discover some excuse to be up there always, to search for stray mushrooms—they will be stray, for the crop is gathered extremely early in the morning—or to make a list of flowers and grasses; to do anything, and, if not, go always without any pretext. Lands of gold have been found, and lands of spices and precious merchandise: but this is the land of health."

Seated near the edge of the cliff one realises, as it is possible nowhere else to realise, except perhaps at Dover, the truth of Edgar's description of the headland in King Lear. It seems difficult to think of Shakespeare exploring these or any Downs, and yet the scene must have been in his own experience; nothing but actual sight could have given him the line about the crows and choughs:

Come on, sir; here's the place:—stand still.—How fearful

And dizzy 't is, to cast one's eyes so low!

The crows and choughs, that wing the midway air,

Show scarce so gross as beetles: half way down

Hangs one that gathers samphire—dreadful trade!

Methinks he seems no bigger than his head:

The fishermen, that walk upon the beach,

Appear like mice; and yond tall anchoring bark,

Diminish'd to her cock; her cock, a buoy

Almost too small for sight: the murmuring surge,

That on the unnumber'd idle pebbles chafes,

Cannot be heard so high.—I'll look no more,

Lest my brain turn, and the deficient sight

Topple down headlong.

Choughs are rare at Beachy Head, but jackdaws and gulls are in great and noisy profusion; and this reminds me that it was on Beachy Head in September, 1886, that the inspiration of one of the most beautiful bird-poems in our language came to its author—the ode "To a Seamew" of Mr. Swinburne. I quote five of its haunting stanzas:

We, sons and sires of seamen, The lark knows no such rapture, |

The old lighthouse on Beachy Head, the Belle Tout, which first flung its beams abroad in 1831, has just been superseded by the new lighthouse built on the shore under the cliff. Near the new lighthouse is Parson Darby's Hole—a cavern in the cliff said to have been hewed out by the Rev. Jonathan Darby of East Dean as a refuge from the tongue of Mrs. Darby. Another account credits the parson with the wish to provide a sanctuary for shipwrecked sailors, whom he guided thither on stormy nights by torches. In a recent Sussex story by Mr. Horace Hutchinson, called A Friend of Nelson, we find the cave in the hands of a powerful smuggler, mysterious and accomplished as Lavengro, some years after Darby's death.

A pleasant walk from Eastbourne is to Birling Gap, a great smuggling centre in the old days, where the Downs dip for a moment to the level of the sea. Here at low tide one may walk under the cliffs. Richard Jefferies, in the essay from which I have already quoted, has a beautiful passage of reflections beneath the great bluff:—"The sea seems higher than the spot where I stand, its surface on a higher level—raised like a green mound—as if it could burst in and occupy the space up to the foot of the cliff in a moment. It will not do so, I know; but there is an infinite possibility about the sea; it may do what it is not recorded to have done. It is not to be ordered, it may overleap the bounds human observation has fixed for it. It has a potency unfathomable. There is still something in it not quite grasped and understood—something still to be discovered—a mystery.

"So the white spray rushes along the low broken wall of rocks, the sun gleams on the flying fragments of the wave, again it sinks, and the rhythmic motion holds the mind, as an invisible force holds back the tide. A faith of expectancy, a sense that something may drift up from the unknown, a large belief in the unseen resources of the endless space out yonder, soothes the mind with dreamy hope.

"The little rules and little experiences, all the petty ways of narrow life, are shut off behind by the ponderous and impassable cliff; as if we had dwelt in the dim light of a cave, but coming out at last to look at the sun, a great stone had fallen and closed the entrance, so that there was no return to the shadow. The impassable precipice shuts off our former selves of yesterday, forcing us to look out over the sea only, or up to the deeper heaven.

"These breadths draw out the soul; we feel that we have wider thoughts than we knew; the soul has been living, as it were, in a nutshell, all unaware of its own power, and now suddenly finds freedom in the sun and the sky. Straight, as if sawn down from turf to beach, the cliff shuts off the human world, for the sea knows no time and no era; you cannot tell what century it is from the face of the sea. A Roman trireme suddenly rounding the white edge-line of chalk, borne on wind and oar from the Isle of Wight towards the gray castle at Pevensey (already old in olden days), would not seem strange. What wonder could surprise us coming from the wonderful sea?"

Beachy Head from the Shore.

The road from Birling Gap runs up the valley to East Dean and Friston, two villages among the Downs. Parson Darby's church at East Dean is small and not particularly interesting; but it gave Horsfield, the county historian, the opportunity to make one of his infrequent jokes. "There are three bells," he writes, "and 'if discord's harmony not understood,' truly harmonious ones." Horsfield does not note that one of these three bells bore a Latin motto which being translated signifies

Surely no bell beneath the sky

Can send forth better sounds than I?

The East Dean register contains a curious entry which is quoted in Grose's Olio, ed. 1796:—"Agnes Payne, the daughter of Edward Payne, was buried on the first day of February. Johan Payne, the daughter of Edward Payne, was buried on the first day of February.

"In the death of these two sisters last mentioned is one thing worth recording, and diligently to be noted. 'The elder sister, called Agnes, being very sicke unto death, speechless, and, as was thought, past hope of speakinge; after she had lyen twenty-four hours without speach, at last upon a suddayne cryed out to her sister to make herself ready and to come with her. Her sister Johan being abroad about other business, was called for, who being come to her sicke sister, demaundinge how she did, she very lowde or earnestly bade her sister make ready—she staid for her, and could not go without her. Within half an houre after, Johan was taken very sicke, which increasinge all the night uppone her, her other sister stille callinge her to come away; in the morninge they both departed this wretched world together. O the unsearchable wisdom of God! How deepe are his judgments, and his ways past fyndinge out!

"Testified by diverse oulde and honest persons yet living; which I myself have heard their father, when he was alive, report.

"Arthur Polland, Vicar; Henry Homewood, John Pupp, Churchwardens."

Friston church is interesting, for it contains one of the most beautiful monuments in Sussex, worthy to be remembered with that to the Shurleys at Isfield. The family commemorated is the Selwyns, and the monument has a very charming dado of six kneeling daughters and three babies laid neatly on a tasseled cushion, under the reading desk—a quaint conceit impossible to be carried out successfully in these days, but pretty and fitting enough then. Of the last of the Selwyns, "Ultimus Selwynorum," who died aged twenty, in 1704, it is said, with that exquisite simplicity of exaggeration of which the secret also has been lost, that for him "the very marble might weep." Friston Place, the home of the Selwyns, has some noble timbers, and a curious old donkey-well in the garden.

West Dean, which is three miles to the west, by a bleak and lonely road amid hills and valleys, is just a farm yard, with remains of very ancient architecture among the barns and ricks. The village, however, is more easily reached from Alfriston than Eastbourne.