Hudibras/The Life of Samuel Butler

I. Ross delint.—G.P. Wainwright sculptt.

BUTLER'S TENEMENT

Near Strensham, Worcestershire

The life of a retired scholar can furnish but little matter to the biographer: such was the character of Mr Samuel Butler, author of Hudibras. His father, whose name was likewise Samuel, had an estate of his own of about ten pounds yearly, which still goes by the name of Butler's tenement; he likewise rented lands at three hundred pounds a year under Sir William Eussel, lord of the manor of Strensham, in Worcestershire. He was a respectable farmer, wrote a clerk-like hand, kept the register, and managed all the business of the parish. From his landlord, near whose house he lived, the poet imbibed principles of loyalty, as Sir William was a most zealous royalist, and spent great part of his fortune in the cause, being the only person exempted from the benefit of the treaty, when Worcester surrendered to the parliament in the year 1646. Our poet's father was elected churchwarden of the parish the year before his son Samuel was born, and has entered his baptism, dated February 8th, 1612, with his own hand, in the parish register. He had four sons and three daughters, born at Strensham; the three daughters and one son older than our poet, and two sons younger: none of his descendants, however, remain in the parish, though some are said to be in the neighbouring villages.

Our author received his first rudiments of learning at home; but was afterwards sent to the college school at Worcester, then taught by Mr Henry Bright,[1] prebendary of that cathedral, a celebrated scholar, and many years master of the King's school there; one who made his profession his delight, and, though in very easy circumstances, continued to teach for the sake of doing good.

How long Mr Butler continued under his care is not known, but, probably, till he was fourteen years old. There can be little doubt that his progress was rapid, for Aubrey tells us that "when but a boy he would make observations and reflections on everything one said or did, and censure it to be either well or ill;" and we are also informed in the Biography of 1710 (the basis of all information about him), that he "became an excellent scholar." Amongst his schoolfellows was Thomas Hall, well known as a controversial writer on the Puritan side, and master of the free-school at King's Norton, where he died; John Toy, afterwards an author, and master of the school at Worcester; William Rowland, who turned Romanist, and, having some talent for rhyming satire, wrote lampoons at Paris, under the title of Rolandus Palingenius; and Warmestry, afterwards Dean of Worcester.

Whether he was ever entered at any university is uncertain. His early biographer says he went to Cambridge, but was never matriculated: Wood, on the authority of Butler's brother, says, the poet spent six or seven years there; but there is great reason to doubt the truth of this. Some expressions in his works look as if he were acquainted with the customs of Oxford, and among them coursing, which was a term peculiar to that university (see Part iii. c. ii. v. 1244); but this kind of knowledge might have been easily acquired without going to Oxford; and as the speculation is entirely unsupported by circumstantial proofs, it may be safely rejected. Upon the whole, the probability is that Butler never went to either of the Universities. His father was not rich enough to defray the expenses of a collegiate course, and could not have effected it by any other means, there being at that time no exhibitions at the Worcester School.

Some time after Butler had completed his education, he obtained, through the interest of the Russels, the situation of clerk to Thomas Jefferies, of Earl's Croombe, Esq., an active justice of the peace, and a leading man in the business of the province. This was no mean office, but one that required a knowledge of law and the British constitution, and a proper deportment to men of every rank and occupation; besides, in those times, when large mansions were generally in retired situations, every large family was a community within itself: the upper servants, or retainers, being often the younger sons of gentlemen, were treated as friends, and the whole household dined in one common hall, and had a lecturer or clerk, who, during meal-times, read to them some useful or entertaining book.

Mr Jefferies' family was of this sort, situated in a retired part of the country, surrounded by bad roads, the master of it residing constantly in Worcestershire. Here Mr Butler, having leisure to indulge his inclination for learning, probably improved himself very much, not only in the abstruser branches of it, but in the polite arts: and here he studied painting. "Our Hogarth of Poetry," says Walpole, "was a painter too;" and, according to Aubrey, his love of the pencil introduced him to the friendship of that prince of painters, Samuel Cooper. But his proficiency seems to have been but moderate, for Mr Nash tells us that he recollects "seeing at Earl's Croombe, some portraits said to be painted by him, which did him no great honour as an artist, and were consequently used to stop up windows."[2] He heard also of a portrait of Oliver Cromwell, said to be painted by him.

After continuing some time at Earl's Croombe, how long is not exactly known, he quitted it for a more agreeable situation in the household of Elizabeth Countess of Kent, who lived at Wrest, in Bedfordshire. He seems to have been attached to her service,[3] as one of her gentlemen, to whom she is said to have paid £20 a year each. The time when he entered upon this situation, which Aubrey says he held for several years, may be determined with some degree of accuracy by the fact that he found Selden there, and was frequently engaged by him in writing letters and making translations. It was in June, 1628, after the prorogation of the third parliament of Charles I., that Selden, who sat in the House of Commons for Lancaster, retired to Wrest for the purpose of completing, with the advantages of quiet and an extensive library, his labours on the Marmora Arundelliana; and we may presume that it was during the interval of the parliamentary recess, while Selden was thus occupied, that Butler, then in his seventeenth year, entered her service. Here he enjoyed a literary retreat during great part of the civil wars, and here probably laid the groundwork of his Hudibras, as, besides the society of that living library, Selden, he had the benefit of a good collection of books. He lived subsequently in the service of Sir Samuel Luke, of Cople Hoo farm, or Wood End, in that county, and his biographers are generally of opinion that from him he drew the character of Hudibras:[4] but there is no actual evidence of this, and such a prototype was not rare in those times. Sir Samuel Luke lived at Wood End, or Cople Hoo farm. Cople is three miles south of Bedford, and in its church are still to be seen many monuments of the Luke family, who flourished in that part of the country as early as the reign of Henry VIII. He was knighted in 1624, was a rigid Presbyterian, high in the favour of Cromwell: a colonel in the army of the parliament, a justice of the peace for Bedford and Surrey, scoutmaster-general for Bedfordshire, which he represented in the Long Parliament, and governor of Newport Pagnell. He possessed ample estates in Bedfordshire and Northamptonshire, and devoted his fortune to the promotion of the popular cause. His house was the open resort of the Puritans, whose frequent meetings for the purposes of counsel, prayer, and preparation for the field, afforded Butler an opportunity of observing, under all their phases of inspiration and action, the characters of the men whose influence was working a revolution in the country. But Sir Samuel did not approve of the king's trial and execution, and therefore, with other Presbyterians, both he and his father, Sir Oliver, were among the secluded members. It has been generally supposed that the scenes Butler witnessed on these occasions suggested to him the subject of his great poem. That it was at this period he threw into shape some of the striking points of Hudibras, is extremely probable. He kept a commonplace book, in which he was in the habit of noting down particular thoughts and fugitive criticisms; and Mr Thyer, the editor of his Remains, who had this book in his possession, says that it was full of shrewd remarks, paradoxes, and witty sarcasms.

The first part of Hudibras came out at the end of the year 1662, and its popularity was so great, that it was pirated almost as soon as it appeared.[5] In the Mercurius Aulicus,

a ministerial newspaper, from January 1st to January 8th, 1662 (1663 N.S.), quarto, is an advertisement saying, that "there is stolen abroad a most false and imperfect copy of a poem called Hudibras, without name either of printer or bookseller; the true and perfect edition, printed by the author's original, is sold by Richard Marriot, near St Dunstan's Church, in Fleet-street; that other nameless impression is a cheat, and will but abuse the buyer, as well as the author, whose poem deserves to have fallen into better hands." After several other editions had followed, the first and second parts, with notes to both parts, were printed for J. Martin and H. Herringham, octavo, 1674. The last edition of the third part, before the author's death, was published by the same persons in 1678: this must be the last corrected by himself, and is that from which subsequent editions are generally printed; the third part had no notes put to it during the author's life, and who furnished them (in 1710) after his death is not known.

In the British Museum is the original injunction by authority, signed John Berkenhead, forbidding any printer or other person whatsoever, to print Hudibras, or any part thereof, without the consent or approbation of Samuel Butler (or Boteler), Esq. or his assignees, given at Whitehall, 10th September, 1677: copy of this injunction is given in the note.[6]

The reception of Hudibras at Court is probably without a parallel in the history of books. The king was so enchanted with it that he carried it about in his pocket, and perpetually garnished his conversation with specimens of its witty passages, which, thus stamped by royal approbation, passed rapidly into general currency. Nor was his Majesty

R. Cooper sculpt.

Charles the Second.

From an original picture in the collection of the Duchess of Dorset at Knowle

content with merely quoting Butler; in an access of enthusiasm he sent for him, that he might gratify his curiosity by the sight of a poet who had contributed so largely to his amusement. The Lord Chancellor Hyde showered promises of patronage upon him, and hung up his portrait in his library.[7] Every person about the Court considered it his duty to make himself familiar with Hudibras. It was minted into proverbs and bon mots. No book was so much read. No book was so much cited. From the palace it found its way at once into the chocolate-houses and taverns; and attained a rapid popularity all over the kingdom.

Lord Dorset was so much struck by its extraordinary merit that he desired to be introduced to the author. "His lordship," according to this curious anecdote, "having a great desire to spend an evening as a private gentleman with the author of Hudibras, prevailed with Mr Fleetwood Shepherd to introduce him into his company at a tavern which they used, in the character only of a common friend; this being done, Mr Butler, while the first bottle was drinking, appeared very flat and heavy; at the second bottle brisk and lively, full of wit and learning, and a most agreeable companion; but before the third bottle was finished, he sunk again into such deep stupidity and dulness, that hardly anybody would have believed him to be the author of a book which abounded with so much wit, learning, and pleasantry. Next morning, Mr Shepherd asked his lordship's opinion of Butler, who answered, 'He is like a nine-pin, little at both ends, but great in the middle.'"

Pepys gives us a curious illustration of the sudden and extraordinary success of Hudibras, and the excitement it occasioned in the reading world. See Memoirs, (Bohn's edit.) vol. i. p. 364, 380; vol. ii. p. 68, 72.

It was natural to suppose, that after the Restoration, and the publication of his Hudibras, our poet should have appeared in public life, and have been rewarded for the eminent service which his poem, by giving new popularity to the Cavalier party, and covering their enemies with derision and contempt, did to the royal cause. "Every eye," says Dr Johnson, "watched for the golden shower which was to fall upon its author, who certainly was not without his part in the general expectation." But his innate modesty, and studious turn of mind, prevented solicitations: never having tasted the idle luxuries of life, he did not make for himself needless wants, or pine after imaginary pleasures: his fortune, indeed, was small, and so was his ambition; his integrity of life, and modest temper, rendered him contented. There is good authority for believing, however, that at one time he was gratified with an order on the treasury for 300l. which is said to have passed all the offices without payment of fees, and this gave him an opportunity of displaying his disinterested integrity, by conveying the entire sum immediately to a friend, in trust for the use of his creditors. Dr Zachary Pearce, on the authority of Mr Lowndes of the treasury, asserts, that Mr Butler received from Charles the Second an annual pension of 100l.; add to this, he was appointed secretary to the Earl of Carberry, then lord president of the principality of Wales, and soon after steward of Ludlow castle,[8] an office which he seems to have held in 1661 and 1662, but possibly earlier and later. With all this, the Court was thought to have been guilty of a glaring neglect in his case, and the public were scandalized at its ingratitude. The indigent poets, who have always claimed a prescriptive right to live on the munificence of their contemporaries, were the loudest in their remonstrances. Dryden, Oldham, and Otway, while in appearance they complained of the unrewarded merits of our author, obliquely lamented their private and particular grievances. Nash says that Mr Butler's own sense of the disappointment, and the impression it made on his spirits, are sufficiently marked by the circumstance of his having twice transcribed the following distich with some variation in his MS. common-place book:

In the same MS. he says, "Wit is very chargeable, and not to be maintained in its necessary expenses at an ordinary rate: it is the worst trade in the world to live upon, and a commodity that no man thinks he has need of, for those who have least believe they have most."

——— Ingenuity and wit

Do only make the owners fit

For nothing, but to be undone

Much easier than if th' had none.

But a recent biographer controverts this, and takes a more probable view of it: he says, "The assumption of Butler's poverty appears utterly unfounded. Though not wealthy, he seems, as far as we can judge, to have always lived in comfort, and we know from the statement of Mr Longueville that he died out of debt. Butler was not one of those

Who hoped to make their fortune by the great;

and though no doubt he might have felt he had not been rewarded according to his deserts by his party, he was not entirely neglected. He had received a large share of popular applause, and was probably prouder of that, and of the power of castigating the follies and vices of mankind, even when displayed by those of his own party, than of being a more highly pensioned dependant of a Court that his writings show he despised. He was no 'needy wretch' in want of bread or a dinner; his earliest biographer gives no hint of his distress; he enjoyed friends of his own selection, and the injunction designates him as 'esquire,' a title not altogether so indiscriminately applied as at the present time. The only foundation for the assertion of his poverty consists in his having copied twice, in his common-place book, a distich from the prologue to the tragedy of Constantine the Great, said to have been written by Otway, though it was not acted till 1684, four years after Butler's death. It is supposed he might have seen the MS., or perhaps only heard the thought, as his copies vary from each other and from the lines as they ultimately appeared. It was, however, long the fashion to complain of the scanty reward bestowed ou literary pursuits; yet we are inclined to think, though authors had then a less certain support in the patronage of a few than now when they appeal to a numerous public, that the improvidence of the individual was more to blame than the niggardliness of the patrons, and of this improvidence there does not appear to be the slightest ground for accusing Butler."

Mr Butler spent some time in France, it is supposed when Lewis XIV. was in the height of his glory and vanity, but neither the language nor manners of Paris were pleasing to our modest poet. As some of his observations are amusing, they are inserted in a note.[9] About this time, he married Mrs Herbert, a lady reputed to be of good family, but whether she was a widow, or not, is uncertain, as the evidence is conflicting. With her he expected a considerable fortune, but, through the greater part of it having been put out on bad security, and other losses, occasioned, it is said, by knavery, it was of but little advantage to him. To this some have attributed his severe strictures upon the professors of the law; but, if his censures be properly considered, they will be found to bear hard only upon the disgraceful part of the profession, and upon false learning in general.

How long he continued in office, as steward of Ludlow Castle, is not known, but there is no evidence of his having exercised it after 1662. Anthony a Wood, on the authority of Aubrey, says that he became secretary to Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, when he was Chancellor of Cambridge, but this is doubted by Grey, who nevertheless allows the Duke to have been his frequent benefactor. That both these assertions are false there is reason to suspect from a story told by Packe in his Life of Wycherley, as well as from Butler's character of the Duke, which will be found on next page. The story is this: "Mr Wycherley had always laid hold of any opportunity which offered of representing to the Duke of Buckingham how well Mr Butler had deserved of the royal family by writing his inimitable Hudibras; and that it was a reproach to the Court, that a person of his loyalty and wit should suffer in obscurity and want. The Duke seemed always to listen to him with attention enough; and after some time undertook to recommend his pretensions to his Majesty. Mr Wycherley, in hopes to keep him steady to his word, obtained of his Grace to name a day when he might introduce that modest and unfortunate poet to his new patron. At last, an appointment was made, and the place of meeting was agreed to be the Roebuck. Mr Butler and his friend attended accordingly: the Duke joined, them; but as the devil would have it, the door of the room where they sat was open, and his Grace, who had seated himself near it, observing a pimp of his acquaintance (the creature too was a knight) trip along with a brace of ladies, immediately quitted his engagement, to follow another kind of business, at which he was more ready than in doing good offices to those of desert, though no one was better qualified than he was, both in regard to his fortune and understanding. From that time to the day of his death, poor Butler never found the least effect of his promise." The character drawn by the poet of the Duke of Buckingham, which we annex in a note,[10] will be conclusive that he was not likely to have received any favour at his hands.

Notwithstanding discouragement and neglect, Butler still prosecuted his design, and in 1678, after an interval of nearly 15 years, published the third part of his Hudibras, which closes the poem somewhat abruptly. With this came out the Epistle to the Lady, and the Lady's Answer. How much more he originally intended, and with what events the action was to be concluded, it is vain to conjecture. After this period, we hear nothing of him till his death at the age of G8, which took place on the 25th of November, 1680, in Rose Street,[11] Covent Garden, where he had for some years resided. He was buried at the expense of Mr William Longueville, though he did not die in debt. This gentleman, with other of his friends, wished to have him interred in Westminster Abbey with proper solemnity; but endeavoured in vain to obtain a sufficient subscription for that purpose. His corpse was deposited privately six feet deep, according to his own request, in the yard belonging to the church of Saint Paul's, Covent Garden, at the west end of it, on the north side, under the wall of the church, and under that wall which parts the yard from the common highway. The burial service was performed by the learned Dr Patrick, then minister of the parish, and afterwards Bishop of Ely. In the year 1786, when the church was repaired, a marble monument was placed on the south side of the church on the inside,[12] by some of the parishioners, whose zeal for the memory of the learned poet does them honour: but the writer of the verses seems to have mistaken the character of Mr Butler. The inscription runs thus:

"This little monument was erected in the year 1780, by some of the parishioners of Covent Garden, in memory of the celebrated Samuel Butler, who was buried in this church, A. D. 1680.

Forty years after his burial at Covent Garden, that is, in 1721, John Barber, an eminent printer, and Lord Mayor of London, erected a monument to his memory in Westminster Abbey, with the following inscription:

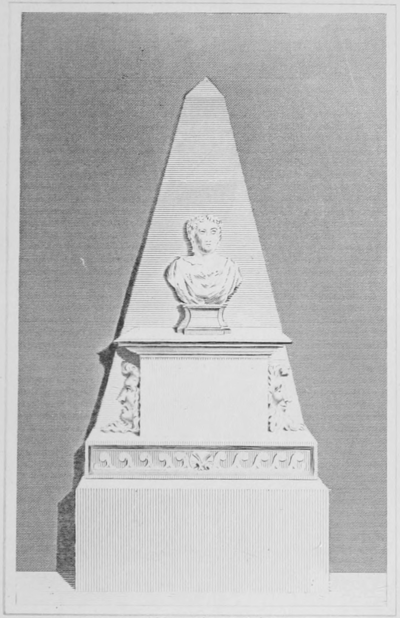

G.P. Wainwright sculptt.

Butler's Monument

Soon after this monument was erected in Westminster Abbey, some persons proposed to erect one in Covent Garden church, for which Mr Dennis wrote the following inscription:

While in London, where Butler died, these tributes to his genius were set up at intervals by men of opposite principles, the place of his birth remained without any memorial until within the last few years, when a white marble tablet, with florid canopy, crockets, and finial, was placed in the parish church of Strensham, by John Taylor, of Strensham Court, Esq., upon whose estate the poet was born. In the design is a small figure of Hudibras, and the face of the tablet bears the following simple inscription:

"This tablet was erected to the memory of Samuel Butler, to transmit to future ages that near this spot was born a mind so celebrated. In Westminster Abbey, among the poets of England, his fame is recorded. Here, in his native village, in veneration of his talents and genius, this tribute to his memory has been erected by the possessor of the place of his birth—John Taylor, Strensham."

What became of the lady he married is unknown, as there is no subsequent trace of her; but it is presumed she died before him. Mr Gilfillan assumes that "subscriptions were raised for his widow," but gives no authority, and we believe none exists.

"Hudibras (says Mr Nash) is Mr Butler's capital work, and though the Characters, Poems, Thoughts, &c. published as Remains by Mr Thyer, in two volumes octavo, are certainly written by the same masterly hand, though they abound with lively sallies of wit, and display a copious variety of erudition, yet the nature of the subjects, their not having received the author's last corrections, and many other reasons which might be given, render them less acceptable to the present taste of the public, which no longer relishes the antiquated mode of writing characters, cultivated when Butler was young, by men of genius, such as Bishop Earle and Mr Cleveland.

The three small volumes, entitled Posthumous Works, in prose and verse, by Mr Samuel Butler, author of Hudibras, printed 1715, 1716, 1717, are all spurious, except the Pindaric Ode on Duval the highwayman, and one or two of the prose pieces. Mr Nash says, "As to the MSS. which after Mr Butler's death came into the hands of Mr Longueville, and from which Mr Thyer published his Genuine Remains in the year 1759; what remain unpublished are either in the hands of the ingenious Doctor Farmer of Cambridge, or myself. For Mr Butler's Common-place Book, mentioned by Mr Thyer, I am indebted to the liberal and public-spirited James Massey, Esq., of Rosthern, near Knotsford, Cheshire."

The poet's frequent and correct use of law terms[14] is a sufficient proof that he was well versed in that science: but if further evidence were wanting, says Mr Nash, "I can produce a MS. purchased of some of our poet's relations, at the Hay, in Brecknockshire, which appears to be a collection of legal cases and principles, regularly related from Lord Coke's Commentary on Littleton's Tenures. The language is Norman, or law French, and the authorities in the margin of the MS. correspond exactly with those given on the same positions in the first institute. The first book of the MS. ends with the 84th section, which same number of sections also terminates the first institute; and the second book is entitled Le second livre del premier part del Institutes de Ley d'Engleterre. It may, therefore, reasonably be presumed to have been compiled by Butler solely from Coke upon Littleton, with no other object than to impress strongly on his mind the sense of that author; and written in Norman, to familiarize himself with the barbarous language in which the learning of the common law of England was at that period almost uniformly expressed.

"As another instance of the poet's great industry, I have a French dictionary, compiled and transcribed by him: thus our ancestors, with great labour, drew truth and learning out of deep wells, whereas our modern scholars only skim the surface, and pilfer a superficial knowledge from encyclopaedias and reviews. It doth not appear that he ever wrote for the stage, though I have, in his MS. common-place book, part of an unfinished tragedy, entitled Nero."

Concerning Hudibras there is but one sentiment. The admirable fecundity of wit, and the infinite variety of knowledge, displayed throughout the poem have been universally admitted. Dr Johnson well expresses the general sense of all its readers when he says, "If Inexhaustible wit could give perpetual pleasure, no eye would ever leave half read the work of Butler; for what poet has ever brought so many remote images so happily together? It is scarcely possible to peruse a page without finding some association of images that was never found before. By the first paragraph the reader is amused, by the next he is delighted, and by a few more strained to astonishment; but astonishment is a toilsome pleasure; he is soon weary of wondering, and longs to be diverted." And he adds, "Imagination is useless without knowledge; nature gives in vain the power of combination, unless study and observation supply materials to be combined. Butler's treasures of knowledge appear proportioned to his experience: whatever topic employs his mind, he shows himself qualified to expand and illustrate it with all the accessaries that books can furnish: he is found not only to have travelled the beaten road, but the by-paths of literature; not only to have taken general surveys, but to have examined particulars with minute inspection."

Various have been the attempts to define or describe the wit and humour of this celebrated poem; the greatest English writers have tried in vain, Cowley,[15] Barrow,[16] Dryden,[17] Locke,[18] Addison,[19], Pope[20] and Congreve, all failed in their attempts; perhaps they are more to be felt than explained, and to be understood rather from example than precept. "If any one," says Nash, "wishes to know what wit and humour are, let him read Hudibras with attention, he will there see them displayed in the brightest colours: there is brilliancy resulting from the power of rapid illustration by remote contingent resemblances; propriety of words, and thoughts elegantly adapted to the occasion: objects which possess an affinity and congruity, or sometimes a contrast to each other, assembled with quickness and variety; in short, every ingredient of wit, or of humour, which critics have discovered, maybe found in this poem. The reader may congratulate himself, that he is not destitute of taste to relish both, if he can read it with delight."

Hudibras is to an epic poem what a good farce is to a tragedy; persons advanced in years generally prefer the former, having met with tragedies enough in real life; whereas the comedy, or interlude, is a relief from anxious and disgusting reflections, and suggests such playful ideas, as wanton round the heart and enliven the very features.

The hero marches out in search of adventures, to suppress those sports, and punish those trivial offences, which the vulgar among the Royalists were fond of, but which the Presbyterians and Independents abhorred; and which our hero, as a magistrate of the former persuasion, thought it his duty officially to suppress. The diction is that of burlesque poetry, painting low and mean persons and things in pompous language and a magnificent manner, or sometimes levelling sublime and pompous passages to the standard of low imagery. The principal actions of the poem are four: Hudibras's victory over Crowdero—Trulla's victory over Hudibras—Hudibras's victory over Sidrophel—and the Widow's antimasquerade: the rest is made up of the adventures of the Bear, of the Skimmington, Hudibras's conversations with the Lawyer and Sidrophel, and his long disputations with Ralpho and the Widow. The verse consists of eight syllables, or four feet; a measure which, in unskilful hands, soon becomes tiresome, and will ever be a dangerous snare to meaner and less masterly imitators.

The Scotch, the Irish, the American Hudibras, and a host of other imitations, are hardly worth mentioning; they only prove the excitement which this new species of poetry had occasioned; the translation into French, by Mr Towneley, an Englishman, is curious, it preserves the sense, but cannot keep up the humour. Prior seems to have come nearest the original, though he is sensible of his own inferiority, and says,

But, like poor Andrew, I advance.

False mimic of my master's dance;

Around the cord awhile I sprawl,

And thence, tho' low, in earnest fall.

His Alma is neat and elegant, and his versification superior to Butler's; but his learning, knowledge, and wit by no means equal. The spangles of wit which he could afford, he knew how to polish, but he wanted the bullion of his master. Hudibras, then, may truly be said to be the first and last satire of the kind; for if we examine Lucian's Trago-podagra, and other dialogues, the Cæsars of Julian, Seneca's Apocolocyntosis, or the mock deification of Claudius, and some fragments of Varro, they will be found very different: the Batrachomyomachia, or battle of the frogs and mice, commonly ascribed to Homer, and the Margites, generally allowed to be his, prove this species of poetry to be of great antiquity.

The inventor of the modern mock heroic was Alessandro Tassoni, born at Modena 1565. His Secchia capita, or Rape of the Bucket, is founded on the popular account of the cause of the civil war between the inhabitants of Modena and Bologna, in the time of Frederick II. This bucket was long preserved, as a trophy, in the cathedral of Modena, suspended by the chain which fastened the gate of Bologna, through which the Modenese forced their passage, and seized the prize. It is written in the ottava rima, the solemn measure of the Italian heroic poets, and has considerable merit. The next successful imitators of the mock-heroic have been Boileau, Garth, and Pope, whose respective works are too generally known, and too justly admired, to require, at this time, description or encomium.

Hudibras has been compared to the Satyre Menippée, first published in France in the year 1593. The subject indeed is somewhat similar, a violent civil war excited by religious zeal, and many good men made the dupes of state politicians. After the death of Henry III. of France, the Duke de Mayence called together the states of the kingdom, to elect a successor, there being many pretenders to the crown; the consequent intrigues were the foundation of the Satyre Menippée, so called from Menippus, an ancient cynic philosopher and rough satirist, introducer of the burlesque species of dialogue. In this work are unveiled the different views and interests of the several actors in those busy scenes, who, under the pretence of public good, consulted only their private advantage, passions, and prejudices. This book, which aims particularly at the Spanish party, went through various editions, from its first publication to 1726, when it was printed at Ratisbon in three volumes, with copious notes and index. In its day it was as much admired as Hudibras, and is still studied by antiquaries with delight. But this satire differs widely from our author's: like those of Varro, Seneca, and Julian, it is a mixture of verse and prose, and though it contains much wit, and Mr Butler had certainly read it with attention, yet he cannot be said to imitate it.

The reader will perceive that our poet had more immediately in view, Don Quixote, Spenser, the Italian poets, together with the Greek and Roman classics;[21] but very rarely, if ever, alludes to Milton, though Paradise Lost was published ten years before the third part of Hudibras.

Other sorts of burlesque have been published, such as the Carmina Macaronica, the Epistolæ obscurorum Virorum, Cotton's Virgil Travesty, &c., but these are efforts of genius of no great importance, and many burlesque and satirical pieces, prose and verse, were published in France between the year 1533 and 1600, by Rabelais, Scarron, and others.

Hudibras operated wonderfully in beating down the hypocrisy and false patriotism of the time. Mr Hayley gives a character of the author in four lines with great propriety:

"Unrivall'd Butler! blest with happy skill

To heal by comic verse each serious ill,

By wit's strong flashes reason's light dispense,

And laugh a frantic nation into sense."

For one great object of our poet's satire is to unmask the hypocrite, and to exhibit, in a light at once odious and ridiculous, the Presbyterians and Independents, and all other sects, which in our poet's days amounted to near two hundred, and were enemies to the king; but his further view was to banter all the false, and even all the suspicious, pretences to learning that prevailed in his time, such as astrology, sympathetic medicine, alchymy, transfusion of blood, trifling conceits in experimental philosophy, fortune-telling, incredible relations of travellers, false wit, and injudicious affectations of poets and romance writers. Thus he frequently alludes to Purchas's Pilgrimes, Sir Kenelm Digby's books, Bulwer's Artificial Changeling, Sir Thomas Brown's Vulgar Errors, Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy, Lilly's Astrology, and the early transactions of the Royal Society. These books were much read and admired in our author's days.

The adventure with the widow is introduced in conformity with other poets, both heroic and dramatic, who hold that no poem can be perfect which hath not at least one Episode of Love.

It is not worth while to inquire, if the characters painted under the fictitious names of Hudibras, Crowdero, Orsin, Talgol, Trulla, &c., were drawn from real life, or whether Sir Roger L'Estrange's key to Hudibras[22] be a true one. It matters not whether the hero were designed as the picture of Sir Samuel Luke, Colonel Rolls, or Sir Henry Rosewell; he is, in the language of Dryden, Knight of the Shire, and represents them all, that is, the whole body of the Presbyterians, as Ralpho does that of the Independents. It would be degrading the liberal spirit and universal genius of Mr Butler, to narrow his general satire to a particular libel on any characters, however marked and prominent. To a single rogue, or blockhead, he disdained to stoop; the vices and follies of the age in which he lived were the quarry at which he flew; these he concentrated, and embodied in the persons of Hudibras, Ralpho, Sidrophel, &c., so that each character in this admirable poem should be considered, not as an individual, but as a species.

Meanings still more remote and chimerical than mere personal allusions, have by some been discovered in Hudibras and the poem would have wanted one of those marks which distinguish works of superior merit, if it had not been supposed to be a perpetual allegory. Writers of eminence, Homer, Plato, and even the Holy Scriptures themselves, have been most wretchedly misrepresented by commentators of this cast. Thus some have thought that the hero of the piece was intended to represent the parliament, especially that part of it which favoured the Presbyterian discipline. When in the stocks, he is said to personate the Presbyterians after they had lost their power; his first exploit against the bear, whom he routs, is assumed to represent the parliament getting the better of the king; after this great victory he courts a widow for her jointure, which is supposed to mean the riches and power of the kingdom; being scorned by her, he retires, but the revival of hope to the Royalists, draws forth both him and his squire, a little before Sir George Booth's insurrection. Magnano, Cerdon, Talgol, &c., though described as butchers, coblers, tinkers, are made to represent officers in the parliament army, whose original professions, perhaps, were not much more noble: some have imagined Magnano to be the Duke of Albemarle, and his getting thistles from a barren land, to allude to his power in Scotland, especially after the defeat of Booth. Trulla means his wife; Crowdero Sir George Booth, whose bringing in of Bruin alludes to his endeavours to restore the king; his oaken leg, called the better one, is the king's cause, his other leg the Presbyterian discipline; his fiddle-case, which in sport they hung as a trophy on the whipping-post, is the directory. Ralpho, they say, represents the Parliament of Independents, called Barebone's Parliament; Bruin is sometimes the royal person, sometimes the king's adherents: Orsin represents the royal party; Talgol the city of London; Colon the bulk of the people. All these joining together against the Knight, represent Sir George Booth's conspiracy, with Presbyterians and Royalists, against the parliament: their overthrow, through the assistance of Ralph, means the defeat of Booth by the assistance of the Independents and other fanatics. These ideas are, per- haps, only the frenzy of a wild imagination, though there may be some lines that seem to favour the conceit.

Dryden and Addison have censured Butler for his double rhymes; the latter nowhere argues worse than upon this subject: "If," says he, "the thought in the couplet be good, the rhymes add little to it; and if bad, it will not be in the power of rhyme to recommend it; I am afraid that great numbers of those who admire the incomparable Hudibras, do it more on account of these doggrel rhymes, than the parts that really deserve admiration."[23] This reflection affects equally all sorts of rhyme, which certainly can add nothing to the sense; but double rhymes are like the whimsical dress of Harlequin, which does not add to his wit, but sometimes increases the humour and drollery of it: they are not sought for, but, when they come easily, are always diverting: they are so seldom found in Hudibras, as hardly to be an object of censure, especially as the diction and the rhyme both suit well with the character of the hero.

It must be allowed that our poet does not exhibit his hero with the dignity of Cervantes: but the principal fault of the poem is, that the parts are unconnected, and the story deficient in sustained interest; the reader may leave off without being anxious for the fate of his hero; he sees only disjecti membra poetæ; but we should remember that the parts were published at long intervals,[24] and that several of the different cantos were designed as satires on different subjects or extravagancies.

Fault has likewise been found, and perhaps justly, with Butler's too frequent elisions, the harshness of his numbers, and the omission of the signs of substantives; his inattention to grammar and syntax, which in some passages obscures his meaning; and the perplexity which sometimes arises from the amazing fruitfulness of his imagination, and extent of his reading. Most writers have more words than ideas, and the reader wastes much pains with them, and gets little information or amusement. Butler, on the contrary, has more ideas than words; his wit and learning crowd so fast upon him, that he cannot find room or time to arrange them: hence his periods become sometimes embarrassed and obscure, and his dialogues too long. Our poet has been charged with obscenity, evil-speaking, and profaneness; but satirists will take liberties. Juvenal, and that elegant poet Horace, must plead his cause, so far as the accusation is well founded.

In the preceding memoir, Dr Nash, the latest and most authentic of Butler's biographers, has been our principal guide; the reader who is desirous of a more critical and elaborate, though sometimes unjustly severe, view of the poem and the poet, will turn without disappointment to the eloquent pages of Dr Johnson.

- ↑ Mr Bright is buried in the cathedral church of Worcester, near the north pillar, at the foot of the steps which lead to the choir. He was born 1562, appointed schoolmaster 1586, made prebendary 1619, died 1626. The inscription in capitals, on a mural stone, now placed in what is called the Bishop's Chapel, is as follows:

Mane hospes et lege,

Magister HENRICUS BRIGHT,

Celeberrimus gymnasiarcha,

Qui scholse regiæ, istic fundatæ per totos 40 annos

summa cum laude præfuit,

Quo non alter magis sedulus fuit, scitusve, ae dexter,

in Latin Græcis Hebraicis litteris,

feliciter edoceudis:

Teste utraque academia quam instruxit affatim

numcrosa plebe literaria:

Sed et totidem annis eoque amplius theologiam professus,

Et hujus ecclesiæ per septennium canonicus major,

Sæpissime hic et alibi sacrum Dei præconem

magno cum zelo et fructu egit.

Vir pius, doctus, integer, frugi, de republica

deque ecclesia optime meritus.

A laboribus per diu noctuque

ad 1626 strenue usque exantlatis

4° Martii suaviter requievit

in Domino.See this epitaph, written by Dr Joseph Hall, dean of Worcester, in Fuller's Worthies, p. 177.

- ↑ In his MS. common-place book is the following observation:

"It is more difficult, and requires a greater mastery of art in painting, to foreshorten a figure exactly, than to draw three at their just length; so it is, in writing, to express anything naturally and briefly, than to enlarge and dilate:

And therefore a judicious author's blots

Are more ingenious than his first free thoughts." - ↑ The Countess is described by the early biographer of Butler as "a great encourager of learning." After the death of the Earl of Kent in 1639 Selden is said to have been domesticated with her at Wrest, and in her town house in White Friars. Aubrey affirms that he was married to her, but that he never acknowledged the marriage till after her death, on account of some law affairs. The Countess died in 1651, and appointed Selden her executor, leaving him her house in White Friars.

- ↑ See notes at page 4.

- ↑ The first part was ready November 11th, 1662, when the author obtained an imprimatur, signed J. Berkenhead; but the date of the title is 1663, and Sir Roger L'Estrange granted an imprimatur for the second part, dated November 6th, 1663.

- ↑ CHARLES R. Our will and pleasure is, and we do hereby strictly charge and command, that no printer, bookseller, stationer, or other person whatsoever within our kingdom of England or Ireland, do print, reprint, utter or sell, or cause to be printed, reprinted, uttered or sold, a book or poem called Hudibras, or any part thereof, without the consent and approbation of Samuel Boteler, Esq. or his assignees, as they and every of them will answer the contrary at their perils. Given at our Court at Whitehall, the tenth day of September, in the year of our Lord God 1677, and in the 29th year of our reign. By his Majesty's command,

Jo. BERKENHEAD.

Miscel. Papers, Mus. Brit. Bibl. Birch, No. 4293. - ↑ Aubrey says, "Butler printed a witty poem called Hudibras, which took extremely, so that the King and Lord Chancellor Hyde would have him sent for. They both promised him great matters, but to this day he has got no employment." Evelyn, writing to Pepys in August, 1689, speaks of Butler's portrait as being hung in the Chancellor's dining-room; "and, what was most agreeable to his lordship's general humour, old Chaucer, Shakspeare, Beaumont and Fletcher, who were both in one piece, Spenser, Mr Waller, Cowley, Hudibras, which last was placed in the room where he used to eat and dine in public, most of which, if not all, are at Cornbury, in Oxfordshire."

- ↑ It was at Ludlow Castle that Milton's Comus was first acted.

- ↑ "The French use so many words, upon all occasions, that if they did not cut them short in pronunciation, they would grow tedious,and insufferable.

"They infinitely affect rhyme, though it becomes their language the worst in the world, and spoils the little sense they have to make room for it, and make the same syllable rhyme to itself, which is worse than metal upon metal in heraldry: they find it much easier to write plays in verse than in prose, for it is much harder to imitate nature, than any deviation from her; and prose requires a more proper and natural sense and expression than verse, that has something in the stamp and coin to answer for the alloy and want of intrinsic value. I never came among them, but the following line was in my mind:

Raucaque garrulitas, studiumque inane loquendi;

for they talk so much, they have not time to think; and if they had all the wit in the world, their tongues would run before it.

"The present king of France is building a most stately triumphal arch in memory of his victories, and the great actions which he has performed: but, if I am not mistaken, those edifices which bear that name at Home were not raised by the emperors whose names they bear (such as Trajan, Titus, &c.), but were decreed by the Senate, and built at the expense of the public; for that glory is lost which any man designs to consecrate to himself.

"The king takes a very good course to weaken the city of Paris by adorning of it, and to render it less by making it appear greater and more glorious; for he pulls down whole streets to make room for his palaces and public structures.

"There is nothing great or magnificent in all the country, that I have seen, but the buildings and furniture of the king's houses and the churches; all the rest is mean and paltry.

"The king is necessitated to lay heavy taxes upon his subjects in his own defence, and to keep them poor in order to keep them quiet; for if they are suffered to enjoy any plenty, they are naturally so insolent, that they would become ungovernable, and use him as they have done his predecessors: but he has rendered himself so strong, that they have no thoughts of attempting anything in his time. "The churchmen overlook all other people as haughtily as the churches and steeples do private houses.

"The French do nothing without ostentation, and the king himself is not behind with his triumphal arches consecrated to himself, and his impress of the sun, nec pluribus impar.

"The French king, having copies of the best pictures from Rome, is as a great prince wearing clothes at second-hand; the king in his prodigious charge of buildings and furniture docs the same thing to himself that he moans to do by Paris, renders himself weaker by endeavouring to appear the more magnificent; lets go the substance for the shadow." - ↑ "A Duke of Bucks is one that has studied the whole body of vice. His parts are disproportionate, and, like a monster, he has more of some and less of others than he should have. He has pulled down all that fabric which nature raised to him, and built himself up again after a model of his own. He has dammed up all those lights that nature made into the noblest prospects of the world, and opened other little blind loopholes backwards, by turning day into night, and night into day. His appetite to his pleasures is diseased and crazy, like the pica in a woman, that longs to eat what was never made for food, or a girl in the green sickness, that cats chalk and mortar. Perpetual surfeits of pleasure have filled his mind with bad and vicious humours (as well as his body with a nursery of diseases), which makes him affect new and extravagant ways, as being tired and sick of the old. Continual wine, women, and music put false values upon things, which by custom become habitual, and debauch his understanding, so that he retains no right notion nor sense of things. And as the same dose of the same physic has no operation on those that are much used to it, so his pleasures require a larger proportion of excess and variety to render him sensible of them. He rises, cats, and goes to bed by the Julian account, long after all others that go by the new style; and keeps the same hours with owls and the antipodes. He is a great observer of the Tartars' customs, and never eats till the great Cham, having dined, makes proclamation that all the world may go to dinner. He does not dwell in his house, but haunt it, like an evil spirit that walks all night to disturb the family, and never appears by day. He lives perpetually benighted, runs out of his life, and loses his time, as men do their ways, in the dark; and as blind men arc led by their dogs, so he is governed by some mean servant or other that relates to him his pleasures. He is as inconstant as the moon, which he lives under; and, although he does nothing but advise with his pillow all day, he is as great a stranger to himself as he is to the rest of the world. His mind entertains all things very freely, that come and go; but, like guests and strangers, they are not welcome if they stay long. This lays him open to all clients, quacks, and impostors, who apply to every particular humour while it lasts, and afterwards vanish. Thus with St Paul, though in a different sense, he dies daily, and only lives in the night. He deforms nature, while he intends to adorn her, like Indians that hang jewels in their lips and noses. His ears are perpetually drilled with a fiddlestick. He endures pleasures with less patience than other men do pains."

- ↑ A narrow and now rather obscure street, which runs circuitously from King Street, Covent Garden, to Long Acre. The site of the house is not now known. Curll the bookseller carried on his business here at the same time, and Dryden lived within a stone's throw in Long Acre, "over against Rose Street."

- ↑ This monument was a tablet, which of late years was affixed under the vestry-room window in that part of the church-yard where his body is supposed to lie. In 1854, when the church-yard was closed against further burials, the tablet, then in a dilapidated condition, was carted away with other debris.

- ↑ Translation.—Sacred to the memory of Samuel Butler, who was born at Strensham, in Worcestershire, in 1612, and died in London, in 1680,—a man of great learning, acuteness, and integrity; happy in the productions of his intellect, not so in the remuneration of them; a super-eminent master of satirical poetry, by which he lifted the mask of hypocrisy, and boldly exposed the crimes of faction. As a writer, he was the first and last in his peculiar style. John Barber, a citizen of London, in 1721, by at length erecting this marble, took care that he, who wanted almost everything when alive, might not also want a tomb when dead. For an Engraving of the Monument, see Dart's Westminster Abbey, vol. i. plate 3.

- ↑ Butler is said to have been a member of Gray's-inn, and of a club with Cleveland and other wits inclined to the royal cause.

- ↑ In his Ode on Wit.

- ↑ In his Sermon against Foolish Talking and Jesting.

- ↑ In his Preface to an Opera called the State of Innocence.

- ↑ Essay on Human Understanding, b.ii. c.2.

- ↑ Spectator, No. 35 and 32.

- ↑ Essay concerning Humour in Comedy, and Corbyn Morris's Essay on Wit, Humour, and Raillery.

- ↑ The editor has in his possession a copy of the first edition of the two parts of Hudibras, appended to which arc about 100 pages of contemporary manuscript, indicating the particular passages of preceding writers which Butler is supposed to have had in view. Among the authors most frequently quoted are: Cervantes (Don Quixote), Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Juvenal and Persius, Catullus, Tibullus and Propertius, Lucan, Martial, Statius, Suetonius, Justin, Tacitus, Cicero, Aulus Gellius, Macrobius, Plinii Historia Naturalis, and Erasmi adagia.

- ↑ First published in 1714.

- ↑ Spectator, No. 60.

- ↑ The Epistle to Sidrophel, not till many years after the canto to wh1ch it is annexed.