John Brown (Du Bois)/Chapter 11

CHAPTER XI

THE BLOW

"Woe unto them that call evil, good; and good, evil."

"At eight o'clock on Sunday evening, Captain Brown said: 'Men, get on your arms; we will proceed to the Ferry.' His horse and wagon were brought out before the door, and some pikes, a sledge-hammer and a crowbar were placed in it. The captain then put on his old Kansas cap, and said: 'Come, boys!' when we marched out of the camp behind him, into the lane leading down the hill to the main road."[1]

The orders given commanded Owen Brown, Merriam and Barclay Coppoc to watch the house and arms until ordered to bring them toward the Ferry. Tidd and Cook were to cut the telegraph lines and Kagi and Stephens to detain the bridge guard. Watson Brown and Taylor were to hold the bridge over the Potomac, and Oliver Brown and William Thompson the bridge over the Shenandoah. Jerry Anderson and Dauphin Thompson were to occupy the engine-house in the arsenal yard, while Hazlett and Edwin Coppoc were to hold the armory.

During the night Kagi and Copeland were to seize and guard the rifle factory, and others were to go out in the country and bring in certain masters and their slaves.

It was a cold dark night when the band started. Ahead was John Brown in his one-horse farm-wagon, with pikes, a sledge-hammer and a crowbar. Behind him marched the men silently and at intervals, Cook and Tidd leading. They had five miles to go, over rolling hills and through woods and then down to a narrow road between the cliffs and the Cincinnati and Ohio canal. As they approached the railroad, Cook and Tidd cut the telegraph wires which led to Baltimore and Washington. At the bridge they halted and made ready their arms. At ten o'clock William Williams, one of the watchmen there, was surprised to find himself a prisoner in the hands of Kagi and Stevens, who took him through the covered structure to the town, leaving Watson Brown and Steward Taylor to guard the bridge. The rest of the company entered Harper's Ferry.

The land between the rivers is itself high, though dwarfed by the mountains and running down to a low point where the rivers join. At this place the bridge leads to Maryland. After crossing the bridge to Virginia, about sixty yards up the street, running parallel to the Potomac, was the gate of the armory where the arms were made. On the Shenandoah side about sixty yards from the armory gate is the arsenal, "where the arms were stored. The company proceeded to the armory gate. The watchman tells how the place was captured:

"'Open the gate,' said they; I said, 'I could not if I was stuck,' and one of them jumped up on the pier of the gate over my head, and another fellow ran and put his hand on me and caught me by the coat and held me; I was inside and they were outside, and the fellow standing over my head upon the pier, and then when I would not open the gate for them, five or six ran in from the wagon, clapped their guns against my breast, and told me I should deliver up the key; I told them I could not; and another fellow made an answer and said they had not time now to be waiting for the key, but to go to the wagon and bring out the crowbar and large hammer, and they would soon get in; they went to the little wagon and brought a large crow-bar out of it; there is a large chain around the two sides of the wagon-gate going in; they twisted the crowbar in the chain and they opened it, and in they ran and got in the wagon; one fellow took me; they all gathered about me and looked in my face; I was nearly scared to death with so many guns about me."[2]

The two captured watchmen, Anderson says, "were left in the custody of Jerry Anderson and Dauphin Thompson, and A. D. Stevens arranged the men to take possession of the armory and rifle factory. About this time, there was apparently

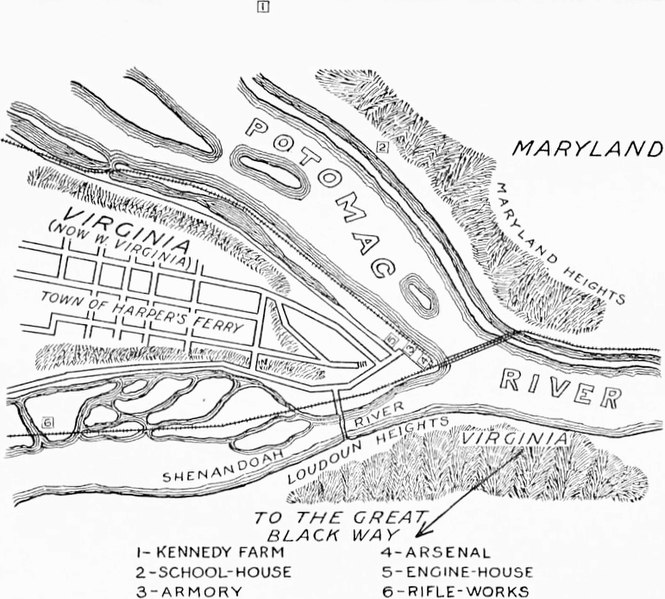

Map of Harper's Ferry, Showing Points Figuring in the Raid

much excitement. People were passing back and forth in the town, and before we could do much, we had to take several prisoners. After the prisoners were secured, we passed to the opposite side of the street and took the armory, and Albert Hazlett and Edwin Coppoc were ordered to hold it for the time being."[3]

The other fourteen men quickly dispersed through the village. Oliver Brown and William Thompson seized and guarded the bridge across the Shenandoah. This bridge was sixty rods from the railway bridge up the river and was the direct route to Loudoun Heights, the slave-filled lower valley, and the Great Black Way. It was, however, not the only way across the Shenandoah: a little more than half a mile farther up were the rifle works, where the stream could be easily forded. Kagi and Copeland went there, captured the watchman and took possession.

"These places were all taken, and the prisoners secured, without the snap of a gun, or any violence whatever," says Anderson, and he continues: "The town being taken, Brown, Stevens, and the men who had no post in charge, returned to the engine-house, where council was held, after which Captain Stevens, Tidd, Cook, Shields Green, Leary and myself went to the country. On the road we met some colored men, to whom we made known our purpose, when they immediately agreed to join us. They said they had been long waiting for an opportunity of the kind. Stevens then asked them to go around among the colored people and circulate the news, when each started off in a different direction. The result was that many colored men gathered to the scene of action. The first prisoner taken by us was Colonel Lewis Washington [a relative of George Washington]. When we neared his house, Captain Stevens placed Leary and Shields Green to guard the approaches to the house, the one at the side, and the other in front. We then knocked, but no one answering, although females were looking from upper windows, we entered the building and commenced a search for the proprietor. Colonel Washington opened his room door, and begged us not to kill him. Captain Stevens replied, 'You are our prisoner,' when he stood as if speechless or petrified. Stevens further told him to get ready to go to the Ferry; that he had come to abolish slavery, not to take life but in self-defense, but that he must go along. The colonel replied: 'You can have my slaves, if you will let me remain.' 'No,' said the captain, 'you must go along too; so get ready.'"[4]

He and his male slaves were thus taken, together with a large four-horse wagon and some arms, including the Lafayette sword. Away the party went and after capturing another planter and his slaves, arrived at the Ferry before daybreak.

Meantime the citizens of the Ferry, returning late from protracted Methodist meeting, were being taken prisoners and about one o'clock in the morning the east-bound Baltimore and Ohio train arrived. This was detained and the local colored porter shot dead by Brown's guards on the bridge. The passengers were greatly excited, but at first thought it was a strike of some kind. After sunrise the train was allowed to proceed, John Brown himself walking ahead across the bridge to reassure the conductor. So Monday, October 17th, began and Anderson says it "was a time of stirring and exciting events. In consequence of the movements of the night before, we were prepared for commotion and tumult, but certainly not for more than we beheld around us. Gray dawn and yet brighter daylight revealed great confusion, and as the sun arose, the panic spread like wild-fire. Men, women and children could be seen leaving their homes in every direction; some seeking refuge among residents, and in quarters further away; others climbing up the hillsides, and hurrying off in various directions, evidently impelled by a sudden fear, which was plainly visible in their countenances or in their movements.

"Captain Brown was all activity, though I could not help thinking that at times he appeared somewhat puzzled. He ordered Lewis Sherrard Leary and four slaves, and a free man belonging in the neighborhood, to join John Henry Kagi and John Copeland at the rifle factory, which they immediately did. . . . After the departure of the train, quietness prevailed for a short time; a number of prisoners were already in the engine-house, and of the many colored men living in the neighborhood, who had assembled in the town, a number were armed."[5]

Up to this point everything in John Brown's plan had worked like clockwork, and there had been but one death. The armory was captured, from twenty-five to fifty slaves had been armed, several masters were in custody and the next move was to get the arms and ammunition from the farm. Cook says that when the party returned from the country at dawn, "I stayed a short while in the engine-house to get warm, as I was chilled through. After I got warm, Captain Brown ordered me to go with C. P. Tidd, who was to take William H. Leeman, and, I think, four slaves [Anderson says fourteen slaves] with him, in Colonel Washington's large wagon, across the river, and to take Terrence Burns and his brother and their slaves prisoners. My orders were to hold Burns and brother as prisoners at their own house, while Tidd and the slaves who accompanied him were to go to Captain Brown's house and to load in arms and bring them down to the schoolhouse, stopping for the Burnses and their guard. William H. Leeman remained with me to guard the prisoners. On return of the wagon, in compliance with orders, we all started for the schoolhouse. When we got there, I was to remain, by Captain Brown's orders, with one of the slaves to guard the arms, while C. P. Tidd, with the other Negroes, was to go back for the rest of the arms, and Burns was to be sent with William H. Leeman to Captain Brown at the armory. It was at this time that William Thompson came up from the Ferry and reported that everything was all right, and then hurried on to overtake William H. Leeman. A short time after the departure of Tidd, I heard a good deal of firing and became anxious to know the cause, but my orders were strict to remain in the schoolhouse and guard the arms, and I obeyed the orders to the letter. About four o'clock in the evening C. P. Tidd came with the second load."[6]

Here, in all probability, was the fatal hitch. The farm was not over three miles from the schoolhouse, and there was a heavy farm-wagon with four large strong horses and a dozen men or more to help. The fact that it took these men eleven hours to move two wagon-loads of material less than three miles is the secret of the extraordinary failure of Brown's foray at a time when victory was in his grasp. That Cook was needlessly dilatory in the moving is certain. He sat down in Byrnes's house and made a speech on human equality. Then Tidd went on to the farm with the wagon and brought a load of arms, which he deposited at the point where the Kennedy farm road meets the Potomac almost at right angles, about three miles or less from the Ferry. The schoolhouse stood here and the children were frightened half to death. Cook stopped at this place and unloaded the wagon, and then Leeman went with Byrnes to the guard-house, lingering and actually sitting beside the road. Even then they arrived before ten o' clock. With haste it is certain that, despite the muddy road, the first load of arms could have been at the school-house before eight o'clock in the morning, and the whole of the stores by ten o'clock. That Brown expected this is shown by his sending William Thompson to reassure the men at the farm of his safety and probably to urge haste; yet when the second load of arms appeared, it was four o'clock in the afternoon, at least three hours after Brown had been completely surrounded. Judging from Cook's narrative, it is likely that Thompson did not see Tidd at all. It was this inexcusable delay on the part of Tidd and Cook and, possibly, William Thompson that undoubtedly made the raid a failure. To be sure, John Brown never said so—never hinted that any one was to blame but himself. But that was John Brown's way.

Events in the town had moved quickly. After Cook had departed, Brown ordered O. P. Anderson "to take the pikes out of the wagon in which he rode to the Ferry, and to place them in the hands of the colored men who had come with us from the plantations, and others who had come forward without having had communication with any of our party."[7]

The citizens were "wild with fright and excitement. . . . The prisoners were also terror-stricken. Some wanted to go home to see their families, as if for the last time. The privilege was granted them, under escort, and they were brought back again. Edwin Coppoc, one of the sentinels at the armory gate, was tired at by one of the citizens, but the ball did not reach him, when one of the insurgents close by put up his rifle, and made the enemy bite the dust. Among the arms taken from Colonel Washington was one double-barreled gun. This weapon was loaded by Leeman with buckshot, and placed in the hands of an elderly slave man, early in the morning. After the cowardly charge upon Coppoc, this old man was ordered by Captain Stevens to arrest a citizen. The old man ordered him to halt, which he refused to do, when instantly the terrible load was discharged into him, and he fell, and expired without a struggle."[8]

The next step which John Brown had in mind is unknown, but there were two safe movements at 9 a. m. Monday morning:

(a) The arms could have been brought across the Potomac bridge and then across the Shenandoah, and so up Loudoun Heights. The men from the Maryland side could have joined, and Brown and his men covered their retreat by compelling the hostages to march with them. Kagi and his men, by wading the Shenandoah, could have supported them.

(b) The arms could have been taken down to the Potomac from the schoolhouse, ferried across and moved over to Kagi. Brown and his men could have joined the party there and all retreated up Loudoun Heights. From the fact that Brown had the arms stopped at the schoolhouse, this seems probably to have been the thought in his mind.

On the other hand, the plan usually attributed to Brown is unthinkable; viz., that he intended retreating across the Potomac into the Maryland mountains. First, he had just come out of the Maryland mountains and had moved down his arms and ammunition; and second, this manœuvre would have cut his band off from the Great Black Way to the South unless he captured the Ferry a second time. Manifestly this, then, was not Brown's idea. It has, however, been suggested that the arms had been moved down to the school-house to be placed in the hands of slaves there. But why were they left on the Maryland side? In the whole Maryland country west of the mountains were less than a thousand able-bodied Negroes, of whom not a tenth could have been cognizant of the uprising, while Brown had arms for 1,200 men or more. No, Brown intended to move the arms in bulk. He had perhaps a ton, or a ton and a half of baggage. He wished it moved first to the school-house, and then if all was well to the Ferry, or straight across to the mountains. Cook started before five o'clock in the morning, and Brown no doubt expected to hear that the arms were at the schoolhouse by ten. At eleven o'clock he dispatched William Thompson to Kennedy farm. Anderson thinks that Thompson's message made the farm party even more leisurely because it told of success so far. This is surely impossible. The veriest tyro must have known that minutes were golden despite the tremendous fortune of the expedition. Did Thompson misapprehend his message? Was the delay Tidd's and what was Owen Brown thinking and doing? It is a curious puzzle, but it is the puzzle of the foray. If the party with the arms had arrived at the bridge any time before noon, the raid would have been successful. Even as it was, Brown still had three courses open to him, all of which promised a measure of success:

(a) He could have gotten his band and crossed back to Maryland,—although this meant the abandonment of the main features of his whole plan. As time waned Stevens and Kagi urged this but Brown refused.

(b) He could have gone to Loudoun Heights, but this would have involved abandoning his arms and stores and above all, one of his sons, Cook, Tidd, Merriam, Coppoc and the slaves. This was unthinkable.

(c) He could have used his hostages to force terms. For not doing this he afterward repeatedly blamed himself, but characteristically blamed no one else for anything.

Meantime every minute of delay aroused the country and brought the citizens to their senses. "The train that left Harper's Ferry carried a panic to Virginia, Maryland and Washington with it. The passengers, taking all the paper they could find, wrote accounts of the insurrection, which they threw from the windows as the train rushed onward."[9]

A local physician says: "I went back to the hillside then, and tried to get the citizens together, to see what we could do to get rid of these fellows. They seemed to be very troublesome. When I got on the hill I learned that they had shot Boerly. That was probably about seven o'clock. . . . I had ordered the Lutheran church bell to be rung to get the citizens together to see what sort of arms they had. I found one or two squirrel rifles and a few shotguns. I had sent a messenger to Charlestown in the meantime for Captain Rowan, commander of a volunteer company there. I also sent messengers to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to stop the trains coming east, and not let them approach the Ferry, and also a messenger to Shepherdstown."[10]

Another eye-witness adds: "There was unavoidable delay in the preparations for a fight, because of the scarcity of weapons; for only a few squirrel guns and fowling-pieces could be found. There were then at Harper's Ferry thousands and tens of thousands of muskets and rifles of the most approved patterns, but they were all boxed up in the arsenal, and the arsenal was in the hands of the enemy. And such, too, was the scarcity of the ammunition that, after using up the limited supply of lead found in the village stores, pewter plates and spoons had to be melted and molded into bullets for the occasion.

"By nine o'clock a number of indifferently armed citizens assembled on Camp Hill and decided that the party, consisting of half a dozen men, should cross the Potomac a short distance above the Ferry, and, going down the tow-path of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal as far as the railway bridge, should attack the two sentinels stationed there, who, by the way, had been reinforced by four more of Brown's party. Another small party under Captain Medler was to cross the Shenandoah and take position opposite the rifle works, while Captain Avis, with a sufficient force, should take possession of the Shenandoah bridge, and Captain Roderick, with some of the armorers, should post themselves on the Baltimore and Ohio Railway west of the Ferry just above the armories."[11]

At last the militia commenced to arrive and the movements to cut off Brown's men began. The Jefferson Guards crossed the Potomac, came down to the Maryland side and seized the Potomac bridge. The local company was sent to take the Shenandoah bridge, leave a guard and march to the rear of the arsenal, while another local company was to seize the houses in front of the arsenal.

"As strangers poured in," says Anderson, "the enemy took positions round about, so as to prevent any escape, within shooting distance of the engine-house and arsenal. Captain Brown, seeing their manœuvres, said, 'We will hold on to our three positions, if they are unwilling to come to terms, and die like men.'"[12]

The attack came at noon from the Jefferson Guards, who started across the Potomac bridge from Maryland. This is Anderson's story:

"It was about twelve o'clock in the day when we were first attacked by the troops. Prior to that, Captain Brown, in anticipation of further trouble, had girded to his side the famous sword taken from Colonel Lewis Washington the night before, and with that memorable weapon, he commanded his men against General Washington's own state. When the captain received the news that the troops had entered the bridge from the Maryland side, he, with some of his men, went into the street, and sent a message to the arsenal for us to come forth also. We hastened to the street as ordered, when he said—'The troops are on the bridge, coming into town; we will give them a warm reception.' He then walked around amongst us, giving us words of encouragement, in this wise:—'Men! be cool! Don't waste your powder and shot! Take aim, and make every shot count!' 'The troops will look for us to retreat on their first appearance; be careful to shoot first.' Our men were well supplied with firearms, but Captain Brown had no rifle at that time; his only weapon was the sword before mentioned.

"The troops soon came out of the bridge, and up the street facing us, we occupying an irregular position. When they got within sixty or seventy yards, Captain Brown said, 'Let go upon them!' which we did, when several of them fell. Again and again the dose was repeated. There was now consternation among the troops. From marching in solid martial columns, they became scattered. Some hastened to seize upon and bear up the wounded and dying,—several lay dead upon the ground. They seemed not to realize, at first, that we would fire upon them, but evidently expected that we would be driven out by them without firing. Captain Brown seemed fully to understand the matter, and hence, very properly and in our defense, undertook to forestall their movements. The consequence of their unexpected reception was, after leaving several of their dead on the field, they beat a confused retreat into the bridge, and there stayed under cover until reinforcements came to the Ferry. On the retreat of the troops, we were ordered back to our former posts."[13]

At this time the Negro, Newby, was killed and his assailant shot in turn by Green. Two slaves also died fighting. Now "there was comparative quiet for a time, except that the citizens seemed to be wild with terror. Men, women and children forsook the place in great haste, climbing up hillsides, and scaling the mountains. The latter seemed to be alive with white fugitives, fleeing from their doomed city. During this time, William Thompson, who was returning from his errand to the Kennedy farm, was surrounded on the bridge by railroad men, who next came up, and taken a prisoner to the Wager house."[14]

It was now one o'clock in the day and while things were going against Brown, his cause was not desperate. His Maryland men might yet attack the disorganized Jefferson Guards in the rear and the arsenal was full of hostages. But militia and citizens kept pouring into the town and by three o'clock "could be seen coming from every direction." Kagi sent word to Brown, urging retreat; but Brown faced a difficult dilemma: Should he go to Loudoun Heights and lose half his men and all his munitions? or should he retreat to Maryland? This latter path lay open, he was sure, by means of his hostages. Meantime the Maryland party might appear at any moment. Indeed, the Jefferson Guards had once been mistaken for them. On this account the message was sent back to Kagi "to hold out for a few minutes, when we would all evacuate the place." Still the Maryland party lingered with the stubborn Tidd somewhere up the road, and Cook idly kicking his heels at the schoolhouse.

The messenger, Jerry Anderson, was fired on and mortally wounded before he reached Kagi, and the latter's party was attacked by a large force and driven into the river.

"The river at that point runs rippling over a rocky bed," writes a Virginian, "and at ordinary stages of the water is easily forded. The raiders, finding their retreat to the opposite shore intercepted by Medler's men, made for a large flat rock near the middle of the stream. Before reaching it, however, Kagi fell and died in the water, apparently without a struggle. Four others reached the rock, where, for a while, they made an ineffectual stand, returning the fire of the citizens. But it was not long before two of them were killed outright and another prostrated by a mortal wound, leaving Copeland, a mulatto, standing alone unharmed upon their rock of refuge.

"Thereupon, a Harper's Ferry man, James H. Holt, dashed into the river, gun in hand, to capture Copeland, who, as he approached him, made a show of fight by pointing his gun at Holt, who halted and leveled his; but, to the surprise of the lookers-on, neither of their weapons were discharged, both having been rendered temporarily useless, as I afterward learned, from being wet. Holt, however, as he again advanced, continued to snap his gun, while Copeland did the same."[15]

Copeland was taken alive and Leeman, with a second message from Kagi to Brown, was killed. Matters were now getting desperate, but the armory was full of prisoners and therein lay John Brown's final hope. Easily as a last resort he could use these citizens as a screen and so escape to the mountains. In attempting this, however, some of the prisoners were bound to be killed and Brown hesitated at sacrificing innocent blood to save himself. He thought that the same end might be accomplished by negotiation. His first move, therefore, was to withdraw all his force and the important prisoners to a small brick building near the armory gate called the "engine-house." Captain Daingerfield, one of the prisoners, says: "He entered the engine-house, carrying his prisoners along, or rather part of them, for he made selections. After getting into the engine-house he made this speech: 'Gentlemen, perhaps you wonder why I have selected you from the others. It is because I believe you to be the most influential; and I have only to say now, that you will have to share precisely the same fate that your friends extend to my men.' He began at once to bar the doors and windows, and to cut port-holes through the brick wall."[16]

This evident weakening of the raiders let pandemonium loose. The citizens realized how small a force Brown had and were filled with fury at his presumption. His men began to fight desperately for their lives.

"About the time when Brown immured himself," a narrator reports, "a company of Berkeley County militia arrived from Martinsburg who, with some citizens of Harper's Ferry and the surrounding country, made a rush on the armory and released the great mass of the prisoners outside of the engine-house, not, however, without suffering some loss from a galling fire kept up by the enemy from 'the fort.'"[17]

This released the arms and one of the Virginia watchmen says: "The people, who came pouring into town, broke into liquor saloons, filled up, and then got into the arsenal, arming themselves with United States guns and ammunition. They kept shooting at random and howling."[18]

The prisoners within the engine-house heard "a terrible firing from without, at every point from which the windows could be seen, and in a few minutes every window was shattered, and hundreds of balls came through the doors. These shots were answered from within whenever the attacking party could be seen. This was kept up most of the day, and, strange to say, not a prisoner was hurt, though thousands of balls were imbedded in the walls, and holes shot in the doors almost large enough for a man to creep through."[19]

The doomed raiders saw "volley upon volley" discharged, while "the echoes from the hills, the shrieks of the townspeople, and the groans of their wounded and dying, all of which tilled the air, were truly frightful." Yet "no powder and ball were wasted. We shot from under cover, and took deadly aim. For an hour before the flag of truce was sent out, the firing was uninterrupted, and one and another of the enemy were constantly dropping to the earth."[20]

Oliver Brown was shot and died without a word and Taylor was mortally wounded. The mayor of the city ventured out, unarmed, to reconnoitre and was killed. Immediately the son of Andrew Hunter, who afterward was state's attorney against Brown, rushed into the hotel after the prisoner William Thompson:

"We burst into the room where he was, and found several around him, but they offered only a feeble resistance; we brought our guns down to his head repeatedly,—myself and another person,—for the purpose of shooting him in the room.

"There was a young lady there, the sister of Mr. Fouke, the hotel-keeper, who sat in this man's lap, covered his face with her arms, and shielded him with her person whenever we brought our guns to bear. She said to us, 'For God's sake, wait and let the law take its course.' My associate shouted to kill him. 'Let us shed his blood,' were his words. All round were shouting, 'Mr. Beckham's life was worth ten thousand of these vile Abolitionists.' I was cool about it, and deliberate. My gun was pushed by some one who seized the barrel, and I then moved to the back part of the room, still with purpose unchanged, but with a view to divert attention from me, in order to get an opportunity, at some moment when the crowd would be less dense, to shoot him. After a moment's thought it occurred to me that that was not the proper place to kill him. We then proposed to take him out and hang him. Some portion of our band then opened a way to him, and first pushing Miss Fouke aside, we slung him out-of-doors. I gave him a push, and many others did the same. We then shoved him along the platform and down to the trestle work of the bridge; he begged for his life all the time, very piteously at first."[21]

Thus he was shot to death as he crawled in the trestle work. The prisoners in the engine-house now urged Brown to make terms with the citizens, representing that this was possible and that he and his men could escape. Brown sent out his son Watson with a white flag, but the maddened citizens paid no attention to it and shot him down. A lull in the fighting came a little later, and Stevens took a second flag of truce, but was captured and held prisoner. Daingerfield says:

"At night the firing ceased, for we were in total darkness, and nothing could be seen in the engine-house. During the day and night I talked much with Brown. I found him as brave as a man could be, and sensible upon all subjects except slavery. He believed it was his duty to free the slaves, even if in doing so he lost his own life. During a sharp fight one of Brown's sons was killed. He fell; then trying to raise himself, he said, 'It is all over with me,' and died instantly. Brown did not leave his post at the port-hole; but when the fighting was over he walked to his son's body, straightened out his limbs, took off his trappings, and then, turning to me, said, 'This is the third son I have lost in this cause.' Another son had been shot in the morning, and was then dying, having been brought in from the street. Often during the affair at the engine-house, when his men would want to fire upon some one who might be seen passing, Brown would stop them, saying, 'Don't shoot; that man is unarmed.' The firing was kept up by our men all day and until late at night, and during this time several of his men were killed, but none of the prisoners were hurt, though in great danger. During the day and night many propositions, pro and con, were made, looking to Brown's surrender and the release of the prisoners, but without result."[22]

Another eye-witness says:

"A little before night Brown asked if any of his captives would volunteer to go out among the citizens and induce them to cease firing on the fort, as they were endangering the lives of their friends—the prisoners. He promised on his part that, if there was no more firing on his men, there should be none by them on the besiegers. Mr. Israel Russel undertook the dangerous duty; the risk arose from the excited state of the people who would be likely to fire on anything seen stirring around the prison-house, and the citizens were persuaded to stop firing in consideration of the danger incurred of injuring the prisoners. . . .

"It was now dark and the wildest excitement existed in the town, especially among the friends of the killed, wounded and prisoners of the citizens party. It had rained some little all day and the atmosphere was raw and cold. Now, a cloudy and moonless sky hung like a pall over the scene of war, and, on the whole, a more dismal night cannot be imagined. Guards were stationed round the engine-house to prevent Brown's escape and, as forces were constantly arriving from Winchester, Frederick City, Baltimore and other places to help the Harper's Ferry people, the town soon assumed quite a military appearance. The United States authorities in Washington had been notified in the meantime, and, in the course of the night, Colonel Robert E. Lee, afterward the famous General Lee of the Southern Confederacy, arrived with a force of United States marines, to protect the interests of the government, and kill or capture the invaders."[23]

Meantime Cook had awakened to the fact that something was wrong. He left Tidd at the school-house and started toward the Ferry; finding it surrounded, he fired one volley from a tree and fled. He found no one at the schoolhouse, but met Tidd, and the whole farm guard, and one Negro on the road beyond. They all turned and fled north, Tidd and Cook quarreling. They wandered fourteen days in rain and snow, and finally all escaped except Cook who went into a town for food and was arrested.

Robert E. Lee, with 100 marines, arrived just before midnight on Monday and one of the prisoners tells the story of the last stand:

"When Colonel Lee came with the government troops in the night, he at once sent a flag of truce by his aid, J. E. B. Stuart, to notify Brown of his arrival, and in the name of the United States to demand his surrender, advising him to throw himself on the clemency of the government. Brown declined to accept Colonel Lee's terms, and determined to await the attack. When Stuart was admitted and a light brought, he exclaimed, 'Why, aren't you old Osawatomie Brown of Kansas, whom I once had there as my prisoner?' 'Yes,' was the answer, 'but you did not keep me.' This was the first intimation we had of Brown's real name. When Colonel Lee advised Brown to trust to the clemency of the government, Brown responded that he knew what that meant,—a rope for his men and himself; adding, 'I prefer to die just here.' Stuart told him he would return at early morning for his final reply, and left him. When he had gone, Brown at once proceeded to barricade the doors, windows, etc., endeavoring to make the place as strong as possible. All this time no one of Brown's men showed the slightest fear, but calmly awaited the attack, selecting the best situations to fire from, and arranging their guns and pistols so that a fresh one could be taken up as soon as one was discharged. . . .

"When Lieutenant Stuart came in the morning for the final reply to the demand to surrender, I got up and went to Brown's side to hear his answer. Stuart asked, 'Are you ready to surrender, and trust to the mercy of the government?' Brown answered, 'No, I prefer to die here.' His manner did not betray the least alarm. Stuart stepped aside and made a signal for the attack, which was instantly begun with sledge-hammers to break down the door. Finding it would not yield, the soldiers seized a long ladder for a battering-ram, and commenced beating the door with that, the party within firing incessantly. I had assisted in the barricading, fixing the fastenings so that I could remove them on the first effort to get in. But I was not at the door when the battering began, and could not get to the fastenings till the ladder was used. I then quickly removed the fastenings; and, after two or three strokes of the ladder, the engine rolled partially back, making a small aperture, through which Lieutenant Green of the marines forced his way, jumped on top of the engine, and stood a second, amidst a shower of balls, looking for John Brown. When he saw Brown, he sprang about twelve feet at him, giving an under-thrust of his sword, striking Brown about midway the body, and raising him completely from the ground. Brown fell forward, with his head between his knees, while Green struck him several times over the head, and, as I then supposed, split his skull at every stroke. I was not two feet from Brown at that time. Of course, I got out of the building as soon as possible, and did not know till some time later that Brown was not killed. It seems that Green's sword, in making the thrust, struck Brown's belt and did not penetrate the body. The sword was bent double. The reason that Brown was not killed when struck on the head was, that Green was holding his sword in the middle, striking with the hilt, and making only scalp wounds."[24]

After the attack on the troops at the bridge, Brown had ordered O. P. Anderson, Hazlett and Green back to the arsenal. But Green saw the desperate strait of Brown and chose voluntarily to go into the engine-house and fight until the last. Anderson and Hazlett, when they saw the door battered in, went to the back of the arsenal, climbed the wall and fled along the railway that goes up the Shenandoah. Here in the cliffs they had a skirmish with the troops but finally escaped in the night, crossed the town and the Potomac and so got into Maryland and went to the farm. It was deserted and pillaged. Then they came back to the schoolhouse and found that empty. In the morning they heard firing and Anderson's narrative continues:

"Hazlett thought it must be Owen Brown and his men trying to force their way into the town, as they had been informed that a number of us had been taken prisoners, and we started down along the ridge to join them. When we got in sight of the Ferry, we saw the troops firing across the river to the Maryland side with considerable spirit. Looking closely, we saw, to our surprise, that they were firing upon a few of the colored men, who had been armed the day before by our men, at the Kennedy farm, and stationed down at the school-house by C. P. Tidd. They were in the bushes on the edge of the mountains, dodging about, occasionally exposing themselves to the enemy. The troops crossed the bridge in pursuit of them, but they retreated in different directions. Being further in the mountains, and more secure, we could see without personal harm befalling us. One of the colored men came toward where we were, when we hailed him, and inquired the particulars. He said that one of his comrades had been shot, and was lying on the side of the mountains; that they thought the men who had armed them the day before must be in the Ferry. That opinion, we told him, was not correct. We asked him to join with us in hunting up the rest of the party, but he declined, and went his way.

"While we were in this part of the mountains, some of the troops went to the schoolhouse, and took possession of it. On our return along up the ridge, from our position, screened by the bushes, we could see them as they invested it. Our last hope of shelter, or of meeting our companions, now being destroyed, we concluded to make our escape north."[25]

Anderson managed to get away, but Hazlett was captured in Pennsylvania and was returned to Virginia. Thus John Brown's raid ended. Seven of the men—John Brown himself, Shields Green, Edwin Coppoc, Stevens and Copeland and eventually Cook and Hazlett—were captured and hanged. Watson and Oliver Brown, the two Thompsons, Kagi, Jerry Anderson, Taylor, Newby, Leary, and John Anderson, ten in all, were killed in the fight, and six others—Owen Brown, Tidd, Leeman, Barclay Coppoc, Merriam and O. Anderson escaped.

At high noon on Tuesday, October 18th, the raid was over. John Brown lay wounded and blood-stained on the floor and the governor of Virginia bent over him.

"Who are you?" he asked.

"My name is John Brown; I have been well known as old John Brown of Kansas. Two of my sons were killed here to-day, and I'm dying too. I came here to liberate slaves, and was to receive no reward. I have acted from a sense of duty, and am content to await my fate; but I think the crowd have treated me badly. I am an old man. Yesterday I could have killed whom I chose; but I had no desire to kill any person, and would not have killed a man had they not tried to kill me and my men. I could have sacked and burned the town, but did not; I have treated the persons whom I took as hostages kindly, and I appeal to them for the truth of what I say. If I had succeeded in running off slaves this time, I could have raised twenty times as many men as I have now, for a similar expedition. But I have failed."[26]

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Report: Reports of Senate, 36th Congress, 1st Session, No. 278; Testimony of Daniel Wheeler, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, p. 33.

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Statement by John Edwin Cook in Hinton, pp. 700–718.

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, p. 37.

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, p. 37–38.

- ↑ Redpath, p. 249.

- ↑ Report: Reports of Senate Committees, 36th Congress, 1st Session, No. 278; Testimony of John D. Starry, p. 25.

- ↑ Boteler, "Recollections of the John Brown Raid" in the Century Magazine, July, 1883, p. 405.

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, p. 42.

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, p. 40.

- ↑ Boteler, "Recollections of the John Brown Raid" in the Century Magazine, July, 1883, p. 407.

- ↑ Daingerfield in the Century Magazine, June, 1885.

- ↑ Barry, Strange story of Harper's Ferry, p. 67.

- ↑ Patrick Higgins in Hinton, p. 290.

- ↑ Daingerfield in the Century Magazine, June, 1885.

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, p. 42.

- ↑ Testimony of Henry Hunter in Redpath, pp. 320–321.

- ↑ Daingerfield in the Century Magazine, June, 1885.

- ↑ Barry, Strange Story of Harper's Ferry, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Daingerfield in the Century Magazine, June, 1885.

- ↑ Anderson, A Voice from Harper's Ferry, p. 52.

- ↑ John Brown in Sanborn, pp. 560–561.