Life with the Esquimaux/Volume 2/Chapter 6

CHAPTER VI.

Encampment on Rae's Point—A Seal Feast—Reindeer Moss abundant—More traditional History—A Two-mile Walk over Rocks-Jack the Angeko—The two Boats and two Kias—Picturesque appearance of the Women Rowers—The Flag of the Free—Icebergs on the Rocks—Visit the Island Frobisher's Farthest—The great Gateway—President's Seat—Beautiful and warm Day—Abundance of Game—Seals and Reindeer in abundance—The Roar of a Cataract—Waters alive with Salmon—Discover the Termination of Frobisher Bay—Enter an Estuary—A Leming—Tweroong sketches Kingaite Coast—Reindeer Skins for Clothing—Luxuriant Fields—Reindeer Tallow good—Innuit Monument—Ancient Dwellings—Sylvia Grinnell River—A Pack of Wolves—Glories of the calm clear Night—Aurora again—A Land abounding with Reindeer—Blueberries—Method of taking Salmon—Bow and Arrows.

On the following morning, Monday, August 19th, 1861, we were in readiness to leave our eighth encampment, and pursue our journey. Starting at 10.15, we crossed the mouth of a deep bay, across which, and about ten miles up from our course, lies a long island, called by the natives Ki-ki-tuk-ju-a. Koojesse informed me that he had been to that "long island," and that the bay extended a considerable distance beyond. The shores of this bay I found to trend about N.N.W. Koojesse also said that it was one day's journey to the head of it from the island. From this, and other data which he furnished, I concluded, and so recorded it in my journal at the time, that the bay is from twenty to twenty-five miles in extent.[1]

Unfortunately for my desire to get on, a number of seals were seen, and my crew were soon engaged in pursuit. This delayed us some time; and when another similar stoppage took place, I felt that it was hopeless to think of going far that day, and accordingly landed, while the Innuits followed what they supposed to be seals, but which, as will shortly be seen, were quite another sort of game.

I walked among gigantic old rocks, well marked by the hand of Time, and then wandered away up the mountains. There I came across an Innuit grave. It was simply a number of stones piled up in such a way as to leave just room enough for the dead body without a stone touching it. All the stones were covered with the moss of generations. During my walk a storm of wind and rain came on, and compelled me to take shelter under the lee of a friendly ridge of rocks. There I could watch Koojesse and his company in the boat advancing toward what was thought an ookgook and many smaller seals. All at once what had seemed to be the ookgook commenced moving, and so likewise did the smaller seals. A slight turn of the supposed game suddenly gave to all a different appearance. I then perceived a boat, with black gunwales, filled with Innuit men, women, and children, and also kias on each side of the boat. Seeing this Koojesse pulled in for me, and we started together for the strangers. A short time, however, proved them to be friends. The large boat contained "Miner," his wife Tweroong, To-loo-ka-ah, his wife Koo-muk (louse), the woman Puto, and several others whom I knew. They were spending the summer up there deer-hunting, and had been very successful. Soon after joining them we all disembarked in a snug little harbour, and erected our tents in company on Rae's Point,[2] which is close by an island called by the natives No-ook-too-ad-loo.

The rain was pouring down when we landed, and the bustle that followed reminded me of similar activity on the steam-boat piers at home. As fast as things were taken out of the boats, such as had to be kept dry were placed under the shelving of rocks until the tupics were up. Then, our encampment formed, all parties had leisure to greet each other, which we did most warmly.

Tweroong was very ill, and appeared to me not far from her death. Her uniform kindness to me wherever I had met her made her condition a source of sadness to me. I could only express my sympathy, and furnish her with a few civilized comforts brought with me. She was the mother of Kooperneung, one of my crew, by her first husband, then deceased.

A great feast was made that evening upon the rocks. A captured ookgook was dissected by four carvers, who proved themselves, as all Innuits are, skilful anatomists. Indeed, as I have before said, there is not a bone or fragment of a bone picked up but the Innuits can tell to what animal it belonged. In the evening I also took a walk about the neighbourhood, and was astonished to see such an abundance of reindeer moss. The ground near our tents was literally white with it, and I noticed many tuktoo tracks.

Our stay at this encampment continued over the next day, and I took the opportunity of questioning Tweroong, who was said to know much about the traditions of her people, as to any knowledge she might possess concerning the coal, brick, and iron at Niountelik. Koojesse was my interpreter, and through him I gained the following information:—

Tweroong had frequently seen the coal there, and likewise heavy pieces of stone (iron) on an island close by. She had often heard the oldest Innuits speak of them. The coal and other things were there long before she was born. She had seen Innuits with pieces of brick that came from there. The pieces of brick were used for brightening the women's hair-rings and the brass ornaments worn on their heads.

She said old Innuits related that very many years ago a boat, or small ship, was built by a few white men on a little island near Niountelik.

I showed her the coal I had brought with me from Niountelik, and she recognized it directly as some like that she had seen.

Owing to the condition of my own boat, I was anxious to have the company of another craft in my voyage up the bay. I accordingly effected an arrangement with the Innuit "Miner" and his party to keep along with me; and on the following day, August 21st, at 9 a.m. we all set out from the encampment to pursue our journey.

While Koojesse and my crew were loading the boat, I ascended a mountain close by, and, after as good a look around as the foggy weather would allow, I began to descend by another path. But I soon found that the way I had chosen was impracticable. The mountain-side was one vast rock, roof-like, and too steep for human feet. Finally, after a long, hard tug down hill, up hill, and along craggy rocks, I gained the beach, and hailed the boat, which took me on board after a walk of two miles.

We made what speed we could to the westward and northward, having to use the oars, the wind being right ahead. In an hour's time we came to an island, where the other boat was stopping awhile. Here I saw "Jack," the angeko, performing the ceremony of ankooting over poor sick Tweroong. The woman was reclining on some tuktoo furs in the boat's bow, while Jack was seated on the tide-wet rocks, making loud exclamations on her behalf. It is very strange what faith these people place in such incantations. I never saw the ceremony otherwise than devoutly attended to. I then took my usual exploring walk upon the island, seeing the bones of a huge whale, portions of which were covered with moss, and the rest bleached to a pure white, but all as heavy as stone.

When we again started, the sight of the two boats and two kias pulling side by side was particularly interesting. There were fourteen souls on board the other boat, men, women, and children, the women pulling at the oars; in each of the two kias was also an Innuit man. The raven hair of the females hanging loosely about the head and face—the flashing ornaments of brass on their heads—their native dress—their methodical rock to and fro as they propelled the boat along, formed, indeed, a striking picture. All were abreast, the two boats and the two kias, and pulling in friendly competition. "Miner" had a flag of checked red, white, and black at the bow of his boat, and the glorious ensign of the United States was streaming to the breeze at the bow of mine. To me the scene was one of indescribable interest. In that region—never before visited by white men, except when Frobisher, three centuries ago, set foot there—it was perfectly novel in its features, and I was truly thankful that I had been blessed with the privilege of raising the "Flag of the Free" in that strange land.

Our progress during the day was not very great, owing to the frequent stoppages of my Innuit crew. Let me be ever so anxious to get on, or to do anything in the way of making observations, if a seal popped up his head, or anything appeared in the shape of game, away they would go in chase, utterly regardless of my wants or wishes. They mean no ill; but the Innuits are like eagles—untameable.

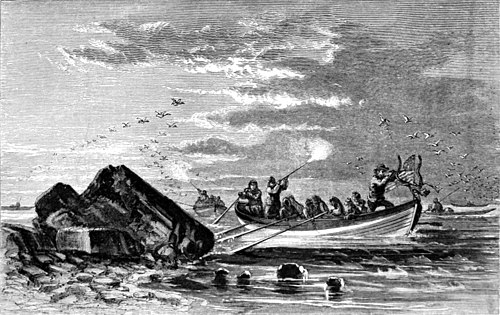

Before reaching our tenth encampment[3] that night, which was similar to the previous one, we passed numerous small bergs, left high and dry on the rocks near the coast by the low spring-tide, as seen in the following engraving.

On the following morning, August 22d, we again set out, making our way among numerous islands, and along land exhibiting luxuriant verdure. Miner's boat and company proceeded on up the bay, while Charley and I were set ashore on the north side of the island "Frobisher's Farthest," leaving instructions with the rest of the crew that we would make our way in two or three hours northerly and westerly to the upper end of the island, where we would get aboard. The place where we landed was very steep, and the ascent was laborious. I had belted to my side my five-pound chronometer, and also a pocket sextant. In my hand I carried a compass tripod and azimuth compass. Charley had his double-barrelled gun, ready for rabbits or any other game.

After getting to the summit the view was very extensive. To the N.W. the appearance was as if the bay continued on between two headlands, one the termination of the ridge of mountains on the Kingaite, Meta Incognita side, and the other the termination of the ridge running on the north side

ICEBERGS ON THE ROCKS.—GREAT FALL OF TIDE.

of Frobisher Bay. The coast of Kingaite was in full view, from the "Great Gateway"[4] down to the "President's Seat,"[5] a distance of one hundred nautical miles. A line of islands—their number legion—shoot down from "Frobisher's Farthest" to the Kingaite coast.

At noon and afterward the weather was exceedingly beautiful, and the water as smooth as a mirror. Kingaite side was showing itself in varying tints of blue, its even mountain range covered with snow, throwing a distinct shadow across the surface of the bay. The sun was warm, and yet casting a subdued light on all around. The rocks and mountains upon our right were bare, and of a red hue, while far to the southeast were the eternal snows of the Grinnell glacier.

We encamped,[6] as before, among the friendly Innuits who had accompanied us, and on the next morning (August 23d), at an early hour, I went by myself for a walk among the hills. Mountains near the coast on that side of the bay had disappeared, the land being comparatively low and covered with verdure. I was delighted to find this such a beautiful country; the waters of the bay were teeming with animal life, and I thought that here was indeed the place to found a colony, if anyone should ever renew the attempt in which Frobisher failed.

Before I came back from my walk I perceived the camp-fires sending up their clouds of smoke, and I was soon after partaking of a hearty breakfast, cooked and served in Innuit fashion. Abundance was now the rule. Seals and blubber were so plentiful that quantities were left behind at our encampment. Even whole seals, with the exception of the skins, were frequently abandoned. Thus these children of the icy North live—one day starving, and the next having so much food that they care not to carry it away.

We started at 10 a.m. and passed in sight of more low land, some of which was covered with grass. Seals and ducks were so numerous that it was almost an incessant hunt—more from habit, on the part of the natives, than from necessity. The signs of reindeer being in the neighbourhood were such that the males of my boat's crew landed to seek them. Some of the Innuits of the other boat had done the same, and frequent reports of fire-arms gave evidence that the game was in view. Presently Koojesse returned, having killed one of the largest of the deer, and after some trouble we got some portions of it on board—saddle, skin, hoofs, horns, and skull. My boat soon after carried at her bow not only the American flag, but also the noble antlers of the deer. I felt at home, with the flag of my country as my companion and inspiring theme.

Early in the day, before the shooting of the reindeer, I heard what seemed to be the roar of a cataract, and perceived that we must be approaching some large river. Presently I was astonished by Suzhi saying to me, "Tar-ri-o nar-me" (this is not sea-water). She then took a tin cup, reached over the boat's side, dipped up some of the water, and gave it to me, after first drinking some herself, to show me that it was good. I drank, and found it quite fresh. It was clear that the river was of considerable size, or it could not throw out such a volume of fresh water to a considerable distance from its mouth against a tide coming in.

After a while we came to an estuary where the waters were alive with salmon. My Innuit crew were in ecstasies, and I too was greatly rejoiced.

On a point of land at the mouth of this fine river we pitched our tents,[7] and away went the men for another hunt. They were out all night, and on the next morning, August 24th, returned with two more deer. This, with what had been shot on the previous day, made our list of game four reindeer, besides several seals and sea-birds. We might have had more, but the Innuits were now indifferent to everything but the larger sort.

While at this, our twelfth encampment, there was quite an excitement occasioned among the Innuits by chasing a "rat."

ENTERING OF SYLVIA GRINNELL RIVER, HEAD OF FROBISHER BAY.

There they were, when I went out of my tent, with clubs and stones, ready for battle with the little animal. But lo! in a few moments the rat proved to be a leming—an arctic mouse. It was hunted out of its hiding-place and speedily killed. Shortly after another one was seen, chased, and killed in like manner. Both of them had very fine fur, and two of the Innuit women skinned the pretty little animals for me. I asked Tweroong if her people ever ate such creatures. With a very wry face, she replied in broken English, "Smalley" (little, or seldom).

While we stayed here, Tweroong employed herself in my tupic drawing, with remarkable skill, a rough outline of Frobisher Bay, Resolution Island, and other islands about it, and the north shore of Hudson's Strait. Too-loo-ka-ah also sketched the coast above and below Sekoselar. Every half minute he would punch me with a pencil I had given him, so that I might pay attention to the Innuit names of places. As soon as he had sketched an island, bay, or cape, he would stop, and wait until I had correctly written down the name. At first he was very loth to make the attempt at drawing a map, but the inducement I held out—some tobacco—succeeded, and, for the first time in his life, he put pencil to paper. His sketch was really good, and I have preserved it, together with Tweroong's, to the present time.

The whole of this day, August 24th, and the following day, were passed at the same encampment. All the Innuit men went out hunting, and killed an abundance of game, now valued not for food, of which there was plenty, but for the skins, of which there was very soon quite a large stock on hand. The women were employed in dressing these skins,[8] and in such other work as always fell to their lot. I was engaged in my observations and in making notes. The weather was delightful, and the scenery around fine. But as I am now writing of that period when I was able to determine the question as to Frobisher "Strait" or Bay, I copy my diary as written on the spot.

"August 25th, 1861, 3.30 a.m.—Another and another is added to the number of beautiful days we've had since starting on this expedition. Can it be that such fine weather is here generally prevailing, while bad weather everywhere else north is the ruling characteristic?

"This certainly is a fact, that here, at the head of Frobisher Bay, a milder climate prevails than at Field Bay and elsewhere, or the luxuriant vegetation that is around here could not be. The grass plain, the grass-clothed hills, are abundant proof of this. I never saw in the States, unless the exception be of the prairies of the West, more luxuriant grasses on uncultivated lands than are here around, under me. There is no mistake in this statement, that pasture-land here, for stock, cannot be excelled by any anywhere, unless it be cultivated, or found, as already excepted, in the great West.[9]

"How is it with the land animals here? They are fat—'fat as butter.' The paunch of the reindeer killed by Koojesse was filled to its utmost capacity with grasses, mosses, and leaves of the various plants that abound here. The animal was very fat, his rump lined with tood-noo (reindeer tallow), which goes much better with me than butter. Superior indeed is it, as sweet, golden butter is to lard. The venison is very tender, almost falling to pieces as you attempt to lift a steak by its edge. So it is with all the tuktoo that have as yet been killed here. Rabbits are in fine condition. Not only are they so now, but they must be nearly in as good order here in winter, for God hath given them the means to make their way through the garb of white, with which He clothes the earth here, for their subsistence.

"Koodloo returned this morning with the skins and tood-noo of three reindeer, which he has killed since his leaving the boat on Friday noon. In all, our party of hunters have killed eleven reindeer, but very little of the venison has been saved—simply the skins and tood-noo.... This afternoon the wife of Jack has been ankooting sick Tweroong. The sun set to-night fine. I never saw more beautiful days and nights than here—the sky with all the mellow tints that a poet could conceive. The moon and aurora now make the nights glorious.

"Monday, August 26th.—This morning not a cloud to be seen. Puto visited me, the kodluna infant at her back. I made her some little presents—pipe, beads, file, and knife, and a small piece of one of the adjuncts of civilization—soap. Somehow I thought it possible that I had made an error of one day in keeping run of the days of the month, but the lunar and solar distances of yesterday have satisfied me that I was correct. I started on a walk up the hills. I came to an Innuit monument, and many relics of former inhabitants—three earth excavations, made when the Innuits built their houses in the ground. I now see a company of eight wolves across the river, howling and running around the rocks—howling just like the Innuit dogs. Now beside a noble river. Its waters are pure as crystal. From this river I have taken a draught on eating by its banks American cheese and American bread. The American flag floats flauntingly over it as the music of its waters seems to be 'Yankee Doodle.' I see not why this river should not have an American name. Its waters are an emblem of purity. I know of no fitter name to bestow upon it than that of the daughter of my generous, esteemed friend, Henry Grinnell. I therefore, with the flag of my country in one hand, my other in the limpid stream, denominate it 'Sylvia Grinnell River.'

"For the first half mile from the sea proper it runs quietly. The next quarter of a mile it falls perhaps fifteen feet, running violently over rocks. The next mile up it is on a level; then come falls again of ten feet in one fifth of a mile; and thence (up again) its course is meandering through low level land. From the appearance of its banks, there are times when the stream is five times the size of the present. Probably in July this annually occurs. The banks are of boulders the first two miles up; thence, in some cases, boulders and grass. Two miles up from where it enters the sea, on the east side, is the neck of a plain, which grows wider and wider as it extends back. It looks from the point where I am as if it were of scores and scores of acres. Thence, on the east side, as far as I can see, there is a ridge of mountains. On the west side of the river, a plain of a quarter to half a mile wide. This is a great salmon river, and so known in this country among the Innuits. At our encampment I picked up the vertebræ of a salmon, the same measuring twenty-one inches, and a piece of the tail gone at that.

"On returning from my ramble this afternoon up Sylvia Grinnell River, saw the wolves again on the other side. They have been howling and barking—Innuit dog-like—all day. I hear them now filling the air with their noise, making a pandemonium of this beautiful place. I now await the return of Koojesse, Kooperneung, and Koodloo, when I hope to have them accompany me with the boat into every bay and to every island in these head-waters of the heretofore called 'Frobisher Strait.'

"The hunting-party has not yet returned; possibly it may continue absent a week. When these Innuits go out in this way they make no preparations, carry no tupic or extra clothing with them. The nights now are indeed cold; near and at the middle of the day, and for four hours after, the sun is hot. This afternoon I started with my coat on, but, getting to the top of the hill, I took it off and left it.

"August 27th,—A splendid sun and a calm air this day. To-morrow I hope to be off, even if Koojesse and party are not back, looking here and there, and taking notes of the country; I can man a boat with the Innuit ladies here if I can do no better. Puto came in with her infant on her back, and in her hand a dish of luscious berries that she had picked this afternoon, presenting the same to me. Of course I gave her some needles and a plug of tobacco in return. The berries are of various kinds, among which are blueberries—called by the Innuits Ki-o-tung-nung—and puong-nung, a small round black berry that has the appearance, but not the taste, of the blueberry.

"This evening, while in the tupic doing up my writing for the day, I was visited by several of the Innuits, among whom were Suzhi and Ninguarping, both well acquainted with this part of the country. I tried to get the former, when she first called, to sketch me Kingaite side of Frobisher Bay, as well as the coast about here; but she, having never used the pencil, felt reluctant to attempt its use, so she called loudly for Ninguarping, who soon came running with all haste to answer to her call. She told him what I wanted, and that he must assist her. I gave him paper and pencil, and he proceeded, giving me very good ideas of the Kingaite side.

"The night is glorious! The sun left the sky in crimson, purple, and all the varied shades that go to make up one of God's beautiful pictures in these regions. The moon now walks up the starry course in majesty and beauty, and the aurora dances in the southern sky.

"Wednesday, August 28th.—Another day of beautiful, glorious weather. Jack called on me early this morning, presenting me with two reindeer tongues. Last evening I received another bountiful present from an Innuit of ripe poung-nung. They taste very much like wild cherries. But what carries me nearest home is the blueberry, it is so like in looks and taste to what we have. Ninguarping and Jack brought me in this afternoon a present of two fine salmon, each measuring twenty inches in length. The Innuits call large salmon Eh-er-loo; small salmon, Eh-er-loo-ung. Salmon are caught by the Innuits with a hook affixed upon a stick, which answers for a handle. They are also caught by spearing them with a peculiar instrument which the Innuits manufacture for themselves.[10]

"On the return of the party, the seal which Kooperneung shot coming in was made the subject of a feast. He (Kooperneung) went around and invited all the men Innuits here, who soon came, each with seal-knife in hand. They squatted around the seal, and opened him up. A huge piece of toodnoo (tuktoo tallow) in one hand, and seal liver in the other, I did justice to the same and to myself. The Innuits and myself through, the ladies took our places. They are now feasting on the abundance left. Seal is the standing dish of provision among the Innuits. They never tire of it; while for tuktoo, Ninoo, ducks, salmon, &c. they soon find all relish gone.

"Too-loo-ka-ah shot his deer with Koojesse's gun. He usually uses only bow and arrows, the same being in universal use among the Innuits on the north side of Hudson's Strait. This evening I got Toolookaah to try his skill in using these instruments—bow and arrow—in making a mark of my felt hat one hundred feet off. The arrow shot from his bow with almost the speed of a rifle-ball. The aim was a trifle under. He missed 'felt,' and lost his arrow, which is no small matter. Its force buried it in the ground, covered by the luxuriant grass, and all our long search proved unsuccessful. The arrow is made with great pains, pointed with iron, spear-shaped."

- ↑ I effected a complete exploration of this bay and the island named on a sledge-journey which I made in the spring of 1862. This, however, will come in its proper place in the sequel of my narrative.

- ↑ Named by the author after Dr. John Rae, the well-known English arctic explorer. Rae's Point, place of our ninth encampment, is in lat. 63° 20′ N. long. 67° 33′ W.

- ↑ In lat. 63° 32′ N. long. 67° 51′ W. by a small cove one mile north of the important island I have named "Frobisher's Farthest," called by the Innuits Ki-ki-tuk-ju-a.

- ↑ The opening between the two headlands alluded to above, which are about ten miles to the north-west of the head of the Bay of Frobisher, I named the "Great Gateway."

- ↑ The most conspicuous mountain on the coast of Frobisher Bay I named President's Seat, after the chief executive officer of the United States government. President's Seat is in lat. 62° 39′ N. long. 66° 40′ W.

- ↑ Our eleventh encampment was in lat. 63° 38′ N. long. 68° 10′ W.

- ↑ Our twelfth encampment was in lat. 63° 43′ 30″, long. 68° 25′. It was on the west side of Sylvia Grinnell River, on a narrow strip of land called Tu-nu-zhoon, the south extreme of which is Ag-le-e-toon, which I named Tyler Davidson Point, after Tyler Davidson, of Cincinnati, Ohio.

- ↑ The skins of the reindeer killed in August and September are valued above others, for the reason that winter dresses can be made only of them. At the time mentioned they are covered with long, thick, and firmly-set hair.

- ↑ To a person going to the arctic regions direct from the pasture-land of the Middle States, this passage of my diary would naturally seem too strong; but when one has been for a year continually among ice, snow, and rugged rocks, as was the case with me, the sight of a grassy plain and green-clad hills could hardly fail to startle him into enthusiastic expression.

- ↑ There is a third method of catching salmon much practised: a kind of trap, called tin-ne-je-ving (ebb-tide fish trap), is made by inclosing a small space with a low wall, which is covered at high tide and dry at low water. The salmon go into the pen over the wall, but are left by the receding tide till it is too low to return the same way, and they thus become an easy prey.