Mexico, California and Arizona/Chapter 19

XIX.

A WEEK AT A MEXICAN COUNTRY-HOUSE.

I.

With a taste for country life, so novel a domain to explore, and constantly agreeable weather, I found a week's stay at the hacienda one of the most agreeable of experiences. From a distance the extensive habitation has a stately air, like some ducal residence. In approaching it you pass first through fields of maguey and blossoming alfalfa, then by a long stone corral for cattle, extensive barracks and huts of laborers, and a pond bordered with weeping willows. It is built of rubble-masonry and plaster, whitewashed, and consists of a single liberal story. The dwelling, with numerous connected buildings, makes in all a facade of about six hundred feet. A belfry, with two tiers of bronze bells hung in arches, sets off the centre. The large windows are defended by cage-like iron gratings. A door, flanked by holy-water fonts, at the left of that forming the main entrance, opens into a family chapel. In a gable above the main entrance is inscribed this motto which has not, however, prevented the hacienda from being the scene of more than one sack by revolutionary forces:

"En aqueste destierro y soledad disfruto del tesoro de la paz "—"In this retirement and solitude I enjoy the treasure of peace."

Immediately in front of the buildings is laid out, after

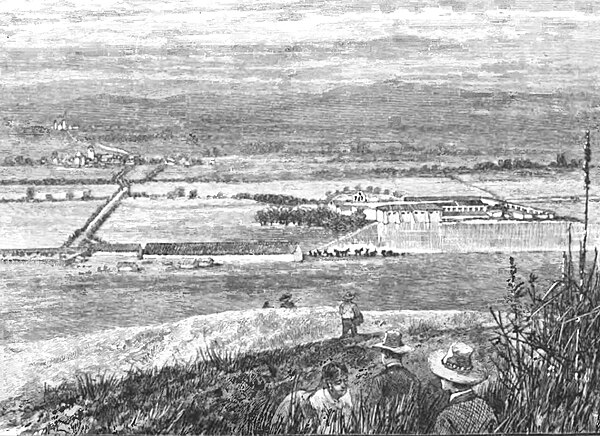

THE HACIENDA OF TEPENACASCO.

Troje de la Teja ("Tiled Roof"); and the "Troje de Limbo" and "Troje de Nuestra Señora del Pilar". The walls of these graneries were of great thickness, in order to preserve the contents cool and at an even temperature. Heavily buttressed, and with their long lines of piers, a yard square, extending down the dim interiors, they are more like basilicas of the early Christian era than simple barns. The central cluster of buildings alone, not counting those detached, covers perhaps four to five acres. Mounting to the roof and looking over its expanse, broken by the openings of numerous courts, you seem to be comtemplating, as it were, some agricultural Louvre or Escorial. Its rear wall is washed by a presa, or artificial pond for irrigation, which stretches away like a lake. Beyond this rises a charming grassy hill, called the Cerro. We climbed the Cerro, and lounged away more than one afternoon there in sketching, and contemplating the beautiful level valley of Tulancingo, spread out below.

The white hacienda with red roofs lay in front, reflecting clearly in the pond. Tulancingo was a white patch at a distance, and other white patches nearer were the hamlets of Jaltepec, Amatlan, and Zupitlan—the latter in ruins. Straight, lane-like roads led from one to another. The mountains on the horizon afforded glimpses of ba– saltic cliffs of the same formation as those at Regla, and of the white smoke of charcoal-burners rising from their forests. Cattle wandered in fine herds in the grassy pasture, each tended by its herdsman and dog. We saw a troop of them at twilight come to drink at the pond, and the complication of all their moving forms was curiously picked out in silhouette against the gleaming brightness of the water.

At evening there returned to the court-yard of the hacienda, to disband after their day's labor, sometimes as many as forty ploughmen. If it had rained they wore their barbaric-looking grass cloaks. They drove yokes of oxen and bulls harnessed to the primitive Egyptian plough, and carried long goads to prod their animals. After them rode in now and then an armed horseman, wrapped in his serape, who overlooked and guarded them at work. At the same time came troops and droves of the other animals needing to be housed: black swine from the grassy slopes of the Cerro; mules released from harness; young horses and mules not yet put to work; milch-cows, and young steers and heifers, each wending its way sedately to its own department.

Most of the cattle, I observed, were hornless. This is brought about by a practice of paring the young horns when first sprouting. It would seem that this might be desirable among ourselves, both on the farm and especially in transporting cattle in the cars ordinarily in use. Milking-time came only once a day—in the morning—and not, as with us, twice. The hind-legs of the cows are lassoed together when being milked. The calves of tender age are also lassoed to the side of the mother, and it is a quaint and amusing sight to see their impatient demonstrations while awaiting the conclusion of the process.

THE THRESHING-FLOOR

the estate was in grass, but irregular patches of ground had been taken out here and there for various crops, and to each was given its special name. Thus the field of San Pablo was devoted to maize and alfalfa; Las Animas, San Antonio the Greater, and San Antonio the Less were given up to maize; Del Monte and San Ignacio el Grande to barley.

The magueyales, or maguey fields, were of considerable extent. The making of the pulque from their product was confided to a special functionary called the tlachiquero. The heart of the maguey is cut out at a certain stage of its growth and a bowl thus formed, into which a quantity of sweet sap continues to run regularly for several months. By the end of that time the plant is dead, and is uprooted and replaced by another. The sap is at first called agua miel, or honey-water, which it resembles. The tlachiquero makes a daily pilgrimage to the fields, and draws off the agua miel by means of a bulky siphon formed of a gourd. Sometimes he bears simply a bag, made of undressed sheepskin, like the wine-skins of Old Spain, on his back; again, he is accompanied by a donkey loaded with a number of these skins. He transfers the sap to these bags, and returns with it to a department of

-

THE TLACHIQUERO.

Without describing the process farther in detail, in a fortnight it is ready for sale or for home consumption.

The pasture fields have their distinctive titles also. There were, for instance, San Gaetano, San Ysidro, and San Dionysio; and, again, the corrals of San Ricardo, San Gaetano, and Las Palmas, where cattle were enclosed at various times. Dairy-farming was the principal industry of the estate. Its neat cattle numbered seventeen hundred head. The pay-roll showed a total for the week of eight hundred and fifty men and boys.

The living apartments of the dwelling were set along two sides of an arcaded court-yard, which had a dismantled fountain in the centre. Offices and store-rooms occupied the other two sides. A department for the butter and cheese making had a special court to itself in the rear. One of the store-rooms contained an ample supply of agricultural implements. Those of the slighter sort, I learned, such as ploughs, spades, picks, hammers, and the coa, a peculiar cutting-hoe, are made in the country, at Apulco, not far distant, where are also iron-works. An iron plough made at Apulco costs $7, while the imported American plough costs $10. There are wooden pitch-forks and spades among the implements. The wooden, or Egyptian, plough is much more in use than that of iron. It consists simply of a wooden beam shod with an iron point, and has an adjustable cross-piece for service in case the furrow needs to be made wider. The purpose to which it is most applied is that of turning shallow furrows between rows of corn, and for this it appears well enough adapted. At Pensacola, in the state of Puebla, such larger pieces of agricultural machinery as reapers, mowers, and separators are manufactured.

-

II.

We happened, among other accommodations, in our exploration of the corridors, upon a prison, described as for use in locking up the refractory peons when they will not work.

"Can you do that? Have you, then, such an absolute power over them?" I asked our host, in some surprise.

"Why, no," he replied, in effect, deprecatingly, "I suppose not; but, you see, now and then it is the only way to manage them, and we have to. It is not civilizated, that people," he continued, in an English which left something to be desired, "and we do the best what we can."

This seems something very like a feudal control on the part of the hacendado, but his numerous dependents do not seem to complain of it. Cases of protest before the magistrates are rarely known, and should they be made it is not likely, since the magistrates are friends of their masters, and of the same social station, that they would meet with any great attention.

We found this laboring population living in squalid stone huts, often six and eight persons in a room. The floors were simply the dirt of the ground, and there was sometimes not even so much as the usual straw mat to sleep or sit upon. We were told here again that the peons are avaricious. They are believers in a general way, but not greatly given to religion. Few attend the services at the chapel, even on Sunday. They summon the priest when about to die, but not otherwise. But few of the children go to school. As a whole, they seemed about as wretched as the poor Irish, except for the advantage over the latter in climate. In every interior is seen a woman on her knees, rolling or spatting the interminable tortillas.

- The laborers on the pay-roll were of two classes

- those employed by the week, and those employed by the year, the former "found themselves;" the latter were "found" by the estate, and paid a certain sum at the end of the year. Wages ran from six cents a day for the boys to

thirty-seven for the best class of adults.

III.

The administrador was assisted, in the management of the hacienda, by the mayor-domo and the sobre-saliente, who acted as his first and second lieutenants; a caporal, who had general charge of the stock; and a pastero, who had charge of the pastures. The pastero it was who indicated the condition of the various areas of pasturage, that the animals might be moved to one after another of them in turn. These minor officers were of the native Indian race. They were dark, swarthy men, very bandit-looking when armed and mounted on horseback, but in reality, when you came to know them, as mild and amible persons as need be wished for.

One, "Don Daniel," supervised the butter and cheese making interest. A book-keeper, "Don Angel," kept an account of all the property of the estate receipts, and disbursements, and an inventory of stock—upon a system which seemed a model of commercial accuracy. Every week a report was forwarded to the owners, at Mexico, upon a printed blank filled out in the most exhaustive detail, so that they could see at a glance how they stood.

The administrador, Don Rafael, was a steady-going man of middle age, a native of San Luis Potosi. He had land and casitas, little houses, of his own, which he rented. He had also a house in the city of Tulancingo, near by, occupied by his family, whom he visited once a week. His salary reached about $1000 a year, and he could be called a person of substance. A conspicuous scar on his forehead led it to be supposed that he might have seen service in the field; but he spoke with contempt of the wars of his country when questioned about it, and said that he had got his scar in breaking a horse.

"A sensible man can always find better occupation than fighting," he said. "I have busied myself with regular industry. The North Americans, now, understand that. They have good ideas. There everybody works and gets a little ahead in the world. Without money in his pocket what is a man good for? He might as well take himself over to the cemetery yonder at once and have done with it."

Don Angel was young, mild, taciturn, painstaking, and a native of Old Spain. His handwriting was small and neat, and he had a great head for details. His salary was the sum of $400 a year. The revenues of the estate which it was his province to cast up amounted, I was told, to $20,000 a year.

Don Daniel, the butter and cheese maker, was young also, but large, handsome, rosy, and had excellent teeth, with coal-black hair and beard. He was a model of robust health and lively spirits. He too had a wife at Tulancingo, whom he visited every Sunday, returning before daylight on Monday morning, to be in time for the milking. He was given to strumming on a guitar in the evening, and assembled around him in his room such convivial spirits as the hacienda afforded. Nonsensical refrains like

"Amarillo si, amarillo no,

Amarillo y verde, me ho pinto,"

were heard proceeding from there long after more staid and decorous persons were in bed. Another member of the household was, let us say, "Manuel," a boy of eighteen, looking younger, who had formerly been a cadet at the national military school. He as here learning the business of a hacienda, or, as some did, he was a young scapegrace whom it was designed to keep out of mischief. At any rate, he was an aide-de-camp to Don Rafael, and took his orders about on horseback. He dressed, like Don Rafael, in a substantial suit of buff leather. He was a very garrulous and communicative person, and, as our attendant and guide in which capacity he offered himself, I think, somewhat as an excuse for escaping more onerous labors—he furnished us much useful information. His elders took a tone of raillery with him, representing him as a very callow, youth, whose views were of no consequence, and who should be seen but not heard from. They ridiculed his French, which he had learned at the military school, even affecting not to believe that it was French at all. Our visit was the occasion for a strenuous effort on his part to set himself right on this point.

"N'ai-je pas bien dit?" he cried to us, across the generous dining-table where we sat together, stretching at the same time a bony, school-boy arm for aid in putting the scoffers down.

One day we mounted to go to a beautiful clear spring of water, which was admired even as early as by Humboldt in his travels. On others we visited the adjacent hamlets, or Tulancingo, from which, later, we were to take the diligence homeward. Again, we made our objective points the various crops, a dam undergoing repairs, or the remoter pastures and corrals.

The herdsman and a boy-assistant at these corrals slept at night in their blankets under a mere pile of stones. The upper irrigating dams are discharged of their waters, when it is desired, by the primitive device of lifting up one cross-beam after another from a narrow gate in the centre. In some of the maize-fields are look-out boxes, aloft on high poles, as a device against crows and other marauders. The general surface over which we rode was the grassy plain, affording a delightful footing for the horses. It was of a fresh, soft green, and enamelled besides with flowers, like violets, the blue maravilla, and many varieties of a yellow flower resembling the dandelion, but prettier.

IV.

The room first entered from the main corridor in the house itself was devoted to the uses of a despacho, or office. Here was the department of Don Angel, and the master himself sometimes took his place behind the long, baize-covered table, strewn with matters of business detail, to hold audience with the peons of the estate, who came, with wide-brimmed hats humbly doffed, to make known various wants and complaints. In the corners stood rifles, spades, and the long branding-iron, which is heated in the month of August to brand the young cattle with the device of their owner.

A fat dark peon enters, and proffers a request for an allowance to be made him for a baptism in his family.

"A baptism?" says the master, briskly. "Well, now, come on! Speak up; don't stand mumbling there! Let us see what your ideas are."

The man suggests, deferentially, to begin with, the sum of $3 for a guajolote, or turkey, as a pièce de résistance for his feast.

"You are always wanting a guajolote, you people. You don't need anything of the kind. However, let us say $1.50—twelve reals—for the guajolote. What next?"

- "The pulque—about forty cuartillas of pulque"

"Twenty cuartillas of pulque" says the master, ruthlessly cutting down the estimate by half. "Well, what next? Speak up!"

The peasant, one of the laborers by the year, perseveres, in his humble, soft voice, regularly making his estimate for each article twice the real figure, and having as regularly cut down. He caps the whole by demanding four reals for a sombrero, well knowing—and knowing perfectly well that his master knows also—that the kind of sombrero he would be likely to want costs but one real.

We had proposed to witness the festivities of this christening, but unfortunately delayed too long at table on the evening of its occurrence, and lost it. But the sky was gloriously full of stars as we went out among the huts and barracks. A woman came out of one of the tenements and made a complaint of a neighbor with whom she had had a row, but got no great sympathy, and hardly seemed to expect any. They are admirably polite, these poor rustics nobody can deny them that. As we sat by the road one day at Amatlan, sketching, some of the women called to us as they went by:

"Buenos dias, señores! Como han pasado, ustedes, la noche? Adios, señores"—"Good-day, sirs! How did you pass the night? Good-bye, sirs!"

We had not in any way first addressed them, and they did not stop, but went swiftly onward, scarcely turning their heads to look. These and many more of the sort are but their ordinary salutations.

The immediate family at the hacienda consisted of one of the several heirs, "Don Eduardo," his wife, mother, and two small children, and their Indian nurses. They were in the habit of spending but a small portion of the year here, and, when they came, lived in quite informal style. Servants and employés, equally with her intimates, called the young mistress "Cholita," a diminutive of her name Soledad. There was little or no receiving or paying of visits, owing to the great distances to be traversed and the scarcity of neighbors.

V.

Social life in the country is hardly known. We had piano music and singing in the evening in a stately, dimly-lighted-salon of the style of the First Empire. One day a large farm vehicle, gayly decorated with boughs, was brought around, all hands got into it, and we proceeded to the lake at Zupitlan for a picnic. The provisions were carried on a litter by a couple of men and a guard on horseback, with his rifle, rode along-side for our protection. Such a precaution was not absolutely needed, perhaps, but there had been a time—before the Governor of Hidalgo had taken his summary measures—when the brigands would have swooped down from the adjacent hills and seized upon such a procession with little ceremony. After dining al fresco we amused ourselves with shooting some of the ducks and cranes which abound on the lake.

We had chocolate and buns on rising in the morning, and two over-liberal repasts, resembling each other in character, at noon and nine in the evening. The dogs swarmed in and out over the house, which presented the aspect of a generous farm rather than a villa.

It was designed in its day for much greater state. The furniture, though battered and ruined now, was of the charming artistic pattern of the First Empire, and all the rooms were large and of fine proportions. In one of

NURSE AND CHILDREN AT THE HACIENDA.

the two principal bedrooms the bed is raised upon a dais, ascended by steps. In the other the corners are cut off by columns, so as to give it an octagon shape. In three of these corners the beds are regularly built in between the columns; the fourth is taken for a door. It so happened that I had not read Madame de la Barca before leaving home. Perhaps I had but a rather disparaging idea of a work descriptive of Mexico coming down no later than 1839. On taking it up after my return I had an opportunity to find how little the country had changed. She too visited this hacienda of Tepenacasco. She noted,

among other items, a quaint wall-paper, of a Swiss pattern, on the octagon room. That very paper is there to this day.

The proprietor was of quite a different sort in those times. He used to give bull-fights in the court before his portal, which is now a threshing-floor, and is said to have entertained half the population of Tulancingo at his table. He finally ruined himself by his extravagance. It is said, among other things, that if he took a sudden notion to go to Mexico, a hundred and twenty miles away, he rode his horses so hard that they sometimes dropped dead under him.