Mexico, California and Arizona/Chapter 23

XXIII.

SAN FRANCISCO (Continued).

I.

KEARNEY STREET (sharing its distinction now with Market Street) is, in sunshiny weather, the promenade of all the leisurely and well-dressed. It abounds in jewellers, who often combine the business of pawnbroking with the other, and are fond of prefixing "Uncle" to their names. Thus, "Uncle Johnson," "Uncle Jackson," or "Uncle Thompson," all along the way, make a genial proffer of their hospitable service. There are shops of Chinese and Japanese goods, though this is not the regular quarter, and "Assiamull and Wassiamull" invite us to inspect the goods of the East Indies.

Perhaps European foreigners of distinction-English lords, M.P.'s, and younger sons, German barons and Russian princes-on their way round the world, are not more numerous than in New York, but they seem more numerous in proportion. The books of the Palace Hotel are seldom free of them, and they are detected, at a glance, strolling on the streets or gazing at the large photographs of the Yosemite Valley and the Big Trees which hang at prominent corners.

There is a genial feeling about Kearney Street, which arises, I think, from its being level at the foot of the steep hills. The temptation is to linger there as long as possible. The instant you leave it for the residence por-

- tion of town you have to begin a back-breaking climb. The ascent is like going up-stairs, and nothing less.

The San Francisco householder of means is "like the herald Mercury new-lighted on a heaven-kissing hill." How in the world, I have asked, does he get up there? Well, by the Cable road. I consider the Cable road one of the very foremost in the list of curiosities, though I have refrained from bringing it forward till now. It is a peculiar kind of tramway, useful also on a level, but invented for the purpose of overcoming steep elevations.

Two cars, coupled, are seen moving, at a high rate of speed, without jar and in perfect safety, up and down all these extraordinary undulations of ground. There is no horse, no steam, no vestige of machinery, no ostensible means of locomotion of any kind. The astonished comment of the Chinaman, observing this marvel for the first time, may be worth repeating once more, old as it is:

"Melican man's wagon, no pushee, no pullee; go top-side hill like flashee."

The solution of the mystery is an endless wire cable hidden in a box in the road-bed, and turning over a great wheel in an engine-house at the top of the hill. The foremost of the two cars is provided with a grip, or pincers, running underneath in a continuous crevice in the box with the cable. When the conductor wishes to go on he clutches with his grip the cable; when he wishes to stop he lets go and puts on a brake. There is no snow and ice to clog the central crevice, which, by the necessities of the case, must be open. The system has been applied, however, with emendations, in Chicago, and also on the great Brooklyn Bridge, at New York.

The great houses on the hill, like almost all the residences of the city, are of wood. It seems a pity, considering the money spent, that this should be so. It is attributed to the superior warmth and dryness of wood in so moist and cool a climate, and also to its security against the shock of earthquakes. Whatever be the reason, the San Francisco Crœsuses have reared for themselves palaces which might be swept off at a breath and leave no trace of their existence. Their architecture has nothing to commend it to favor. They are large, rather over-ornate, and of no particular style.

The Hopkins residence—a costly Gothic chateau, carried out also in wood—may be excepted from this description. The basement stories, however, are of stone, and there is enough work in these and foundations to build many a first-class Eastern mansion. To prepare sites for habitations on the steep hills has been an enormous labor and expense. The part played by retaining–walls, terraces, and staircases is extraordinary. The merest wooden cottage is often prefaced by works which outweigh its own importance a dozen to one.

When a peerage is drawn up for San Francisco, the grader will follow in rank the railroad-builder and the miner. To hardly anybody else has such an amount of lucrative employment been open. What a cutting and filling! what gravelling and paving!

Striking freaks of surface and arrangement result. The city might have been terraced up, like Genoa, or Naples above the Chiaja. It is picturesque still, in the thin, American way, through the absolute force of circumstances. You enter the retaining-walls of stone or plank through door-ways or grated archways like the postern-gates of castles. You pass up stone steps in tunnels or vine-covered arbors within these; or zigzag from landing to landing of long, wooden stairways, without. Odd little terrace streets and "places," as Charles Place, with bits of gardens, are found sandwiched between the

- regular formation. A wide thoroughfare, Second Street-cut through Rincon Hill, the Nob Hill of a former day, to afford access to water for vehicles-has been the

occasion of leaving isolated, high and dry, some few old houses, with cypress-trees about them, approached by wooden staircases almost interminable. Dark at sunset against a red sky, for instance, they present effects to delight the heart of an etcher.

HIGH-GRADE RESIDENCES.

In this line, however, nothing is equal to Telegraph Hill, which bristles with the make-shift contrivances of a much humbler population. Bret Harte lived there at one time, and asserts that the goats used to browse on his pots of geranium in the second-story windows. They also pranced on the roof at night in such a way that a new-comer thought there had been a fine thunder-storm. Elsewhere, instead of precipices, you meet with chasms. Looking down from the roadway, you will see some poor figure of a woman sewing in a bay-window which was once filled with air and sunshine, but now commands only a patch of mildewed wall.

The views from the hills are of no common order. As you rise on the Cable road you hang in the air above the body of the city, and above the harbor and its environment. The Clay Street road, one of the steepest, passes through the Chinese quarter. Half-way up an ensign, of a blue-and-crimson dragon on an orange field, on the Chinese Consulate-general, flies, a bright bit of color in the foreground. The bay, far below the eye, has an opaque look. On some rare days it is very blue in color, but oftener it is of slate or greenish gray. Passing vessels criss-cross their wakes in white upon the green like pencils on a slate.

The atmosphere above it is rarely clear. Some lurking wisp of fog at best is generally stealing in at the Golden Gate, or under dark Tamalpais, watching to rush over and seize upon the city. An obscurity, part of fog and part of smoke, hovers in areas, now enveloping only the town, again the prospect, so that nothing can be seen, though the town itself be free. Now it lifts momentarily from the horizon for glimpses of distant islands and cities, and the peak of Mount Diablo, thirty miles away, and shuts down as suddenly as if these were but figments of a vision.

The view down upon the lights at night is particularly striking. Set in constellations, or radiating in formal lines, they are like the bivouac of a great army. It might be the hosts of Armageddon were encamped round about awaiting the dawn. For several days, from California Street Hill, there was the spectacle of a devastating fire in the woods of Mount Tamalpais. Its dark

- smoke rendered the sunsets lurid and ominous, and at night the burning mountain, reflected in the bay, was a

more terrible Vesuvius or Hecla.

II.

One is hardly supposed to "travel" as yet in America as in Europe. We make our journeys here for definite objects, chiefly on business. No doubt, if we could bring ourselves to the same receptive frame of mind, the same

readiness to be amused by odds-and-ends of experience, a good deal the same kind of pleasure could be got out of it as there. San Francisco at least appears to afford a few of exactly the same details which receive the attention of the leisurely abroad.

Italian fishermen eat macaroni, and drink red wine, and wait upon the tides, about the vicinity of Broadway and Front Streets. The Italian colony, for the rest, is pretty numerous. The part that remains on shore is chiefly composed of grocers, butchers, and restaurateurs. Chinese shrimp-catchers are found in the cove at Potrero, behind the large new manufacturing buildings of that quarter, and again at San Bruno Point, twelve miles down the bay. Their boats and junks are not on a large scale, but display the usual peculiarities of their nautical architecture.

The French colony is also numerous, and the language heard continually on the street. Taking advantage of the variety and excellence of supplies in the markets, French restaurants furnish repasts—including a half-bottle of wine of the country of—extraordinary cheapness. A considerable Mexican and Spanish contingent mingles also with the Italians, along Upper Dupont, Vallejo, and Green Streets. Shops with such titles as La Sorpresa and the Tienda Mexicana adjoin the Unità d'Italia and the Roma saloon. A Mexican militia company turns out, under the green, white, and red tricolor, on every anniversary of the national independence, the 16th of September. During the Carnival season a form of entertainment known as "Cascarone parties" prevails among the Spanish residents. The participants pelt one another with egg-shells filled with gilt and colored papers. Sometimes a canvas fort is erected in the street, and attacked and defended by means of these missiles and handfuls of flour. Such Spanish life as there is can hardly be said to have remained from the early days, since the Spanish settlement at best was infinitesimal. It has been attracted here in the mean time like other immigration. A dusky mother, smoking a cigarette, in a hammock, in a palm-thatched hut, on the Acapulco trail, told me of a son who had gone to San Francisco twenty years before and become a carpenter there. He had forgotten now, she heard, even how to speak his native language.

The Latin race seems to have been especially attracted to the country of a mild climate and original traditions like their own. But German and Scandinavian names too on the sign-boards—Russian Ivanovich and Abramovich, and Hungarian Haraszthy—show that no one blood or influence has exclusive sway. There appears to be an unusually free intermingling and giving in marriage among these various components. They are less clannish than with us. Lady Wortley Montagu remarked, at Constantinople, some hundred years ago, a similar fusion, and believed it a reason for a debased and mongrel race. But a very different class of blood mingles here from that of Orientals at Constantinople. Our much more cheerful theory is, that we are to combine the best qual

chinese fishing-boats in the bay

of the children of San Francisco does nothing as yet to discredit such a theory.

Such vestiges of '49 as yet remain are extremely few. I confess to surprise as well at the slightness of the historic records at the Pioneer Society. I make little doubt that they could be easily paralleled in many other libraries of the country. "North Beach," under Telegraph Hill, may be visited both for its memories and present aspect of picturesque ruin. It is where the pioneer ships landed. Hence, also, the ill-fated Ralston swam out into the bay, and here are the remains of "Harry Meigs's Wharf." Harry Meigs was a famous prototype of Ralston's in the Fifties. Defeated in brilliant financial schemes, and having endeavored to save his defeat by forgery, he was obliged to take flight. He chartered a schooner to take him to the South Sea Islands, which lay off the wharf for him at midnight.

"This is hell," he is reported to have said as he stepped on board, expressing thus his Lucifer-like sense of humiliation and downfall.

He did not remain long at the South Sea Islands, but sailed for Peru. There he began the world again, built all the railways of that republic, became a great millionaire, sent back and paid all his debts, and was divested, by act of Legislature, so far as legislation could do it, of the stigma of his crimes. His story is by no means a good one to hold up to the emulation of youth, but it is romantic, and in some sense characteristic of California.

The blackened old pier is a dumping-place for city refuse now, and swarms of chiffoniers gather around it to pick out such scraps of value as they may before they are washed away by the daily tides. The leading streets of San Francisco commemorate the pioneers of State or place. A newer series adopts the names of the States of the Union, and simple numbers, which are carried already to Forty-fifth, for avenues, and Thirtieth for streets. The fast-growing, tough, fragrant, but scrawny, eucalyptus is much in use as a shade-tree. In the door-yards grow cypresses, the Spanish-bayonet, and the ordinary flowers, needing a great deal of sprinkling to keep them in good order.

The San Francisco school of writers, developed in the successful days of the Overland Monthly, have not made much use of the city itself in their literature. Bret Harte confined his local range to the doings of certain small boys, some "Sidewalkings," and the disagreeable features of the climate, in "Neighborhoods I Have Moved From." It was from Folsom Street that the adventurous Master Charles Summerton, aged five, set out for his great expedition to Van Dieman's Land, by way of the Second and Market Street cars. I had occasion to visit Folsom Street sometimes, and even this slight incident such is the potency of the literary touch has given it a genial interest which many others, as good in appearance, and even stately Van Ness Avenue, on the other side of town—very much better—by no means share.

III.

San Francisco offers, in my view, the advantage of saving a trip around the world. Whoever, having seen Europe, shrinks from farther wanderings may derive here from a compact Chinese city of 30,000 souls such an idea of the life and doings of the Celestial Empire as may

appease curiosity and take the place of a voyage to the Orient.

The Chinese immigrants, it is true, rarely erect buildings of their own, but fit themselves to what they find. They fit themselves in with all their peculiar industries, their smells of tobacco and cooking-oil, their red and yellow signs and hand-bills, opium pipes, high-soled slippers, sticks of India ink, silver pins, and packets of face-powder, their fruits and fish, their curious groceries and more curious butcher's meat—they have fitted all this into the Yankee buildings, and taken such absolute possession that we are no longer in America, but Shanghai or Hong-Kong. The restaurants make the nearest approach to the national façades, but this is brought about by adding highly-decorated balconies, lanterns, and inscriptions, and not building outright.

I had the curiosity to try one of the best of the restaurants—quite a gorgeous affair, at the head of Commercial Street—and found the fare both neatly served and palatable. There was a certain monotony in the bill, which I ascribed to a desire to give us dishes as near the American style as possible. We had chicken-soup, with flour paste resembling macaroni; a very tender chicken, sliced, through bones and all, in a bowl; a bowl of duck; a pewter chafing-dish of quail with spinach. All the food is set out in bowls, and each helps himself, with ebony chopsticks, to such morsels as he desires. The chopsticks, held in the fingers of the right hand, somewhat after the manner of castanets, are about as convenient to the novice as a pair of lead-pencils. We drank saki, or rice brandy, in infinitesimal cups, during the dinner, and at dessert very fine tea.

The upper story of these places is reserved for guests of the better class. Those of slender purses are accommodated below. To these is served a second drawing of the same tea which has been used, and such meats as re

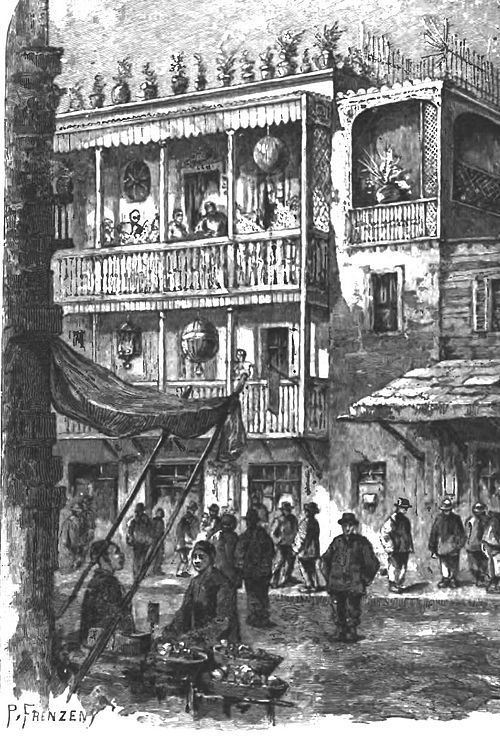

CHINESE QUARTER, SAN FRANCISCO.

screens, lanterns, and teak-wood tables and stools; while below pine-wood tables are deemed good enough.

A BALCONY IN THE CHINESE QUARTER.

Dropping in late one evening for a cup of tea, I had the fortune to witness a supper-party—a novel, genre picture, glowing with color. There were a dozen dignified-looking men, dressed in handsome silk clothing black, blue, and purple. With them were as many women—young, slender, and pretty, of their type, while the women seen walking about the streets are very coarse and clumsy. Their black hair was carefully smoothed, and looped up with silver pins, and their complexions were daintily made of pink and white and vermilion, realizing exactly the heads painted on their silken fans. The most interesting girl was of Fellah, or Hebrew aspect, and was probably not without an admixture of other blood in her veins. The men occupied carved teak-wood stools about a large table, spread with a white cloth, and covered with charming china. The women stood by and served them. Now and then one of the latter rested momentarily on a corner of a stool, in a laughing way, and took a morsel also. The whole was a bit of bright Chinoiserie worth a long journey to witness.

They were very merry, and played, among other amusements, a game like the Italian mora. In this one would hold up fingers in rapid succession, while the others shouted the probable number at the tops of their voices. What with this, their laughter, drumming on the table, and general hubbub, besides an orchestra of their peculiar music adding its din from behind a screen, they were not very unlike a party of Parisian canotiers and grisettes supping at Bougival.

The temple and the theatre of the Chinese emigrant have an identical character wherever he goes. I found here the same scenes in both I had witnessed in Havana at the beginning of my journey. The temple, economically set up in some upper rear room, abounds in gaudy signs and some good bronzes, but is little frequented. The theatre is far more popular. The dresses used here are rich and interesting. The performers are continually marching, fighting, spinning about, pretending to be dead and jumping up again, and singing in high, cracked voices like the whine of a bagpipe. A doughty warrior, who may be Gengis Khan or Timour the Tartar, and bear

IN A CHINESE THEATRE.

The cemetery is more curious even than the theatre of Chinadom in San Francisco. I came upon it in the course of a long stroll one afternoon, and was almost the only spectator of some peculiar ceremonial rites in propitiation of the dead. It is not grouped in the general Golgotha at Lone Mountain, but adjoins that devoted to the city paupers, out among the melancholy sand-dunes by the ocean. It is parcelled off by white fences into a large number of enclosures for separate burial guilds, or tongs. These have large signs upon them—"Fook Yam Tong," "Tung Sen Tong," "Ye On Tong," etc. One has almost difficulty to persuade himself that he is awake witnessing such doings as here take place in the broad sunlight of Yankee-land.

It is the practice to convey the bones of their dead to China, but there are preliminary funerals in regular form. All the "hacks" in San Francisco are often engaged. The bones are left in the ground a year or more before removal.

Toward three in the afternoon a number of express-wagons of the common sort drove up with freights of Chinamen and Chinawomen, and curiously assorted provisions. The "hoodlum" drivers conducted themselves peaceably enough, but seemed to have a certain sardonic air at the idea of having to draw their profits from patrons of such a class. The provisions were unloaded, taken up and laid on small wooden altars, of which there is one at the front of each tong. Most conspicuous were whole roast pigs, decorated with ribbons and colored papers. There were next roast fowls, rice, salads, sweetmeats, fruits, cigars, and rice brandy. The participants set to work to fire revolvers, bombs, and crackers, kindle packages of colored paper, make profound genuflections before the graves, and scatter libations upon them of food and liquors. Only the roast pigs were reserved and taken home again; all the rest was scattered about. The din and smoke increased apace; the strange-garbed figures pranced about like sorcerers, and the decorated pigs loomed out with a goblin air. It seemed a veritable witches' Sabbath. Some of the fruits and cigars were hospitably offered to me as I looked on; and I will say that parsimony does not seem a vice of the Chinaman, though he lives upon so little, and is content with moderate returns.

Coming back the same way in the evening, I noted prowling figures of white men among the graves, gathering up the fragments cast down by the improvident heathen.

I am glad, on the whole, not to have the mooted Chinese question to settle in person. On the one hand, a great law of political economy the natural right of man to seek happiness where he will; on the other, a view that the best good of a community does not necessarily consist

in mere size and value of "improvements." The reflective mind will find it rather in the greatest average distribution of comfort. I should say that there have been no

evils of consequence experienced from the presence of the Chinese population as yet. Without them the railroads could not have been built, nor the agricultural nor mining interests developed. With all the complaint, too, of competition, the wages of white labor are better here than at the East, and the cost of living is certainly not more.

A proper male costume for San Francisco is humorously said to be a linen duster with a fur collar. The variability of the climate within brief spaces of time is thus indicated. It varies largely, in fact, in different parts of the same day, though the mean for the year is remarkably even. The mean for—January the coldest month—is but fifty degrees, and for September—the warmest fifty-eight. It is a famous climate for work, but the average temperature, as is seen, is pretty low for comfort. People go away for warmth in the summer quite as much as for coolness. The rainy season—the winter is really the pleasantest of the year. The air is clearer then, while the prospects are verdant and best worthy to be seen. At other times fogs prevail, or bleak winds arise in the afternoon, and blow dust, in a dreary way, into the eyes of all whose misfortune calls them to be then in the streets.

We return to town from our Chinese ceremony along wide Point Lobos Avenue, the drive to the Cliff House. It is skirted on one side by the public pleasure-ground, Golden Gate Park, an area of half a mile by three miles

and a half, which is being redeemed from an original condition of drifting sand in a wonderful way. All the outer tract near the ocean is as desert and yellow as Sahara. A few scattered dwellings appear in the sands, each with its water-tank and wind-mill, a yucca-plant or two, and some knots of tough grass about it. The city appears on the edge of the steep, as if it were looking over in surprise.