Mexico, California and Arizona/Chapter 26

XXVI.

A WONDROUS VALLEY, AND A DESERT THAT BLOSSOMS

LIKE THE ROSE.

I.

the Yosemite, currently spoken of as the "Valley," is comprised in the belt formed by drawing lines across the State from San Francisco and Monterey respectively. It is a wild, strange nook among the Sierras, one of the few places not only not disappointing, but worthy of far more praise than has ever been bestowed upon it. It is like one of those mysterious regions on the outskirts of

the fairy-land of the story-books a standing resource of adventure to all the characters who enter it, and it is proper enough that our earthly paradise of Southern California should have such a region of enchantment also adjoining it.

I reached it by stage-ride of sixty miles, from the Southern Pacific Railroad, at Madera, to Clark's Station, and thence by stage and horseback of twenty-live miles to the Valley. The autumn days were lovely there. The

foliage, turned by a local climate quite as severe as that of New England, glowed with a vivid richness. The Merced River, a gentle stream, pursuing a devious way in the bottom, which is as level as a floor, reflected the color from many a mirror-like pool and sudden bend. Walls of rock rise on either hand to an elevation of three-quarters of a mile, varying from one-half to one-

eighth of a mile in width. It is rather a chasm than a valley. At night the radiance of a full yellow moon invested all its wonders with an added enchantment. The cliffs are exactly what we think cliffs ought to be, but what they seldom are. They are of the hardest granite, pleasantly gray in color, and terminate in castle and dome like forms. The precipices are sheer and unbroken to the base, with almost none of those slopes of dèbris that detract from precipices in general. It is a little valley suitable, without a hair's-breadth alteration, to the purposes of any giant, enchanter, or yellow dwarf of them all.

It is such scenery as Doré has imagined for the "Idyls of the King." One half feels himself a Sir Lancelot or Sir

Gawain, riding along this lovely and majestic mountain trail; and as if he should wear chain-armor, a winged helmet, and a sword upon which he had sworn to do deeds of redoubtable valor.

It was the coast valleys and some coast towns that we took on our first journey. This time we have come down the main line of the Southern Pacific Railway through the central plain of the State. The railway is traced along the great central valley known as the San Joaquin, on a line nearly midway between the Sierra Nevadas and the Coast Range.

The road is still comparatively new, and the settlements have attained no great dimensions. It did not as a rule touch at the older towns existing, but pursued a direct course through a country where all had to be opened up. As some of the places passed by were of considerable

size no little dissatisfaction ensued, and the mutterings are still heard. Frequent mention of this grievance

is heard by the traveller through Southern California. Some of the neglected places even maintain that they

would have been better without any railroad at all. Ref-

erences are thrown out to former glories of a dazzling sort which it is sometimes difficult to credit, though a railroad naturally effects great innovations in trade. To the ordinary observer it would appear that the introduction of a splendidly equipped railway, even if it distribute its blessings a little unequally at first, and its tariff be

high, must be a great and permanent advantage to everything remote as well as near. For the first time an adequate means has been afforded for the transport of immigrants and supplies through the whole length of the State.

The Southern Pacific Railway has completed connections which give it a transcontinental route from San Francisco, across Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, to New Orleans. Immigrants are to be brought in by steamer from Liverpool to New Orleans, and thence by rail at a rate not to exceed that to the central West. The fares to California heretofore have been almost prohibitive, which is one of the reasons why so rich a country contains as yet less than a million of people. The languid movement hither of the valuable class of immigration which pours into the West, though ascribed by some alarmists to the presence of the Chinese, is due to the cost of travel and the lack of cheap lands for settlement. The Chinese are certainly not rivals in the matter of land, since they acquire little or none of it.

The new opportunities opened to transportation, the depression of the mining interest, and rapid increase of

the Chinese, have awakened of late an exceptional interest in white immigration. A committee of some of the

most prominent persons in the State has opened an inquiry into the most effectual means of promoting it. It will no doubt set forth more clearly than has ever been

done before an account of such territory as is open to set-

tiers, whether offered by the government, the railroads, or the great ranches, its advantages and the methods of reaching it.

It seems a little singular at first that lack of suitable lands can be adduced as a reason for lack of population in so vast a region, with the climate and other natural advantages of which so much has been said. It can only be understood by taking into account the unusual atmospheric dryness, and the important part played by water, which has to be brought upon the soil by costly contrivances. The locations where there is sufficient natural moisture for the maturing of crops are of small extent. They were among the first taken up. In much of the central and southern portions of the State the annual rain-fall is almost infinitesimal in quantity. At Bakersville, the capital of Kern County—whither our journey presently leads us—it is no more than from two to four inches. Light crops of grain and pasturage for stock may occasionally be got even under these conditions, but the only certain reliance is irrigation.

The springs and small streams were early appreciated at their value, and seized upon by persons who controlled with them great tracts of surrounding country, valueless except as watered from these sources. These tributary tracts are used chiefly as cattle and sheep ranges. A person owning five thousand acres will often have for his stock the free run of twenty thousand more. Cultivation is confined to the springs and water-courses, and becomes a succession of charming oases in a desert the superficial sterility of which is phenomenal.

The tenure of land by thousands of acres under a single ownership is a tradition from the Spanish and Mexican times. It has been much decried, as a great evil, and it is said that the State would be much more prosperous in a series of small farms. This is probably true, and the system as it exists may be ascribed in part to the greed of individuals, but it arises principally out of the natural features of the country. The wealth of the large holders alone enables them to undertake works of improvement, such as canal-making, drainage, and tree-planting, on an effectual scale. Perhaps the State will have to lend its assistance, and establish a public system of irrigation and drainage, before the land can be fully prepared for the small settler.

Water! water! water! How to slake the thirst of this parched, brown country, and turn it over to honest toil and thrift, is the great problem as we go southward, and the processes of irrigation are the most distinctive marks upon the landscape wherever it is improved.

II.

It is in early November that we begin to traverse the long San Joaquin Valley from Lathrop Junction, just below Stockton, southward. The side tracks of the railroad are crowded with platform-cars laden with wheat for the sea-board. The "elevator" system is not yet in use, and the grain is contained in sacks for convenient handling.

Hereabouts are some of the most famous wheat ranches. A man will plough but a single furrow a day on his farm, but this may be twenty miles long. There is sufficient rain-fall for the cereals, but not for the more exacting crops. The land gives but few bushels to the acre under the easy system of farming, but it must be remembered that there are a great many acres. The stubble of the grain-fields is whitened with wild-fowl. At a way-station a small rustic in an immense pair of boots goes over to a pool and blazes away with a shot-gun. Presently he returns, dragging by the necks an immense pair of wild-geese, almost beyond his strength to pull. The tawny color of the fields, and the great formal stacks of straw piled up in them, recall some aspects of the central table-land of Mexico. Many or spacious buildings are not necessary in the mild, dry climate of California. The prosperous ranches have, in consequence, a somewhat thin, unfurnished appearance compared with Eastern farms.

The most prominent object at each station is a long, low warehouse of the company, for the accommodation of grain. Like the station buildings generally it is painted Indian red, in "metallic" paint. The station of Merced is one of the two principal points of departure for the Yosemite Valley, Madera the other. At Merced an immense wooden hotel, for travellers bound to the Valley, overshadows the rest of the town. It rises beside the track, and the town is scattered back on the plain.

At Madera appears the end of a V-shaped wooden aqueduct, or flume, for rafting down lumber from the mountains fifty miles away to a planing-mill. Some of the hands also occasionally come down the flume in temporary boats. As the speed is prodigious these voyages abound in excitement and peril. The structure, supported on trestles, according to the formation of the ground, stretches away in interminable perspective to the mountains, which are rose-pink and purple at sunset. The scene is suggestive of the Roman Campagna, with this slight, essentially American work as a parody of the broken aqueducts and temples of the classic ancients. The lumber flume, however, is a bold and costly enterprise, though we be prone to smile at it.

By degrees we draw away from the wheat ranches, more and more on the uncultivated plain. The town of Fresno, two hundred miles below San Francisco, and about midway between two important streams, the San Joaquin and Kings Rivers, is in the midst of a particularly desolate tract, known, up to a very recent period, as the San Joaquin Desert. One should alight here. There is no better place for examining the marvellous capabilities of a soil which appears at first sight inhospitable to the last degree. Fresno is in the hands of enterprising persons, who push and advertise it very actively. We heard at San Francisco of the Fresno Colony, the Central Colony, American Colony, Scandinavian Colony, Temperance Colony, Washington Colony, and others of similar names clustered around Fresno. It is advertised as one of those genial places, alluring to the imagination of most of us, where one can sit down under his own vine and fig-tree, secure from the vicissitudes of climate, and find a profitable occupation open to him in the cultivation of the soil, and all at a moderate cost.

The aspect of things on alighting is very different from what had been expected, but all the substantial advantages claimed seemed realized, and the process of founding a home may be witnessed in all its stages.

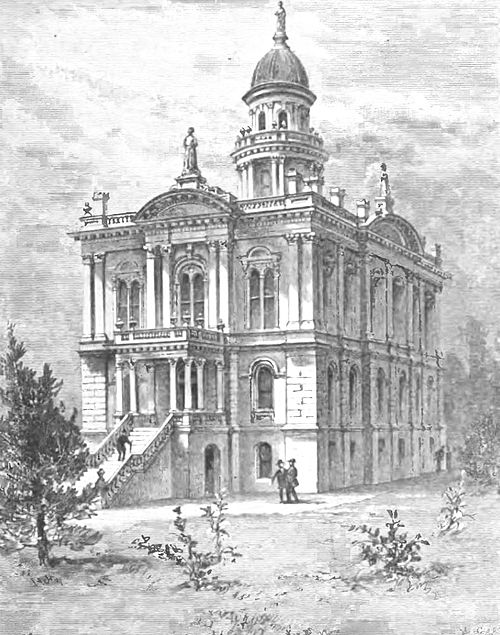

The town has a population of two thousand, most of which it has gained in the past five years. It is set down on the east side of the railroad highway, with a thin scattering of foliage slightly veiling the formality of its lines. It consists of a few streets of two-story wooden and brick buildings. The streets cross one another at right angles, and have planked sidewalks. A slight eminence above the general level is the site of the County Court-house, which somewhat resembles an Italian villa in design, and has Italian cypresses in front. The court-houses of half a dozen counties down the line, from Modesto, the capital of Stanislaus, to Bakersfield, capital of Kern, are identical

COURT-HOUSE AT FRESNO.

in pattern, so that it is both typical of its kind and evidence of an economical spirit.

A sharp distinctness of outline is characteristic of these cities of the plain. Separated from the main part of Fresno by the railroad, as by a wide boulevard, is a row of low wooden houses and shops, as clearly cut out against

the desert as bathing-houses on a beach. This is the Chinese quarter. It tells at a glance the story of the peculiar people who tenant it: the social ostracism on the one hand, and their own indomitable clannishness on the other.

There is now hardly any hamlet so insignificant, even in the wastes of Arizona, that the Chinese have not penetrated it, in search of labor and opportunities. Every settlement of the Pacific slope has its Chinese quarter, as mediaeval towns had their Ghetto for the Jews. It is not always without the place, as at Fresno; but, wherever it be, it constitutes a close corporation and a separate unit. In dress, language, and habits of life it adheres to Oriental tradition with all the persistence the new conditions will admit.

The Celestials do not introduce their own architecture, and they build little but shanties. They adapt what they find to their own purposes, as has been said, distinguishing them with such devices that the character of the dwellers within cannot be mistaken.

A great incongruity is felt between the little Yankee wooden dwellings and the tasselled lanterns, gilded signs, and hieroglyphics upon red and yellow papers with which they are profusely overspread. Here Ah Coon and Sam Sing keep laundries like the Chinese laundry the world over. Yuen Wa advertises himself as a contractor for laborers. Hop Ling, Sing Chong, and a dozen others have miscellaneous stores. In their windows are junk-shaped slippers, opium pipes, bottles of saki, rice-brandy, dried fish, goose livers, gold and silver jewelry, and packets of face-powder and hair ornaments for the women. The pig-tailed merchants themselves sit within, on

odd-looking chests arid budgets, and gossip in animated cackle with customers, or figure up their profits gravely in

brown-paper books, with a brush for

a pen. Women—much more numerous in proportion to the men than is commonly supposed—occasionally waddle by. Their

black hair is very smoothly greased, and kept in place by long silver pins. They wear wide jackets and pantaloons of a cheap black "paper cambric," which increase the natural awkwardness of

their short and ungainly figures.

Up-stairs, in unpainted, cobwebby, second stories, are the joss-houses. Here hideous but decorative idols grin as serenely as if in the centre of their native Tartary, and as if there were no spires of little Baptist and Methodist meeting-houses rising indignantly across the way. Pastilles burn before the idols, and crimson banners are draped about; and there are usually a few pieces of antique bronze upon which the eye of the connoisseur rests enviously.

Other interiors are cabarets, which recall those of the French working-classes. A boisterous animation reigns within. The air is thick with tobacco-smoke of the peculiar Chinese odor. Games of dominoes are played with magpie-like chatter by excited groups around long, wooden tables. Most of those present wear the customary blue cotton blouse and queer little black soft hat, and all have queues, which either dangle behind or are coiled up like the hair of women. Some, however—teamsters, perhaps here only temporarily—are dressed in the slop clothing and cowhide boots of ordinary white laborers.

The Chinamen are servants in the camps, the ranches, and the houses of the better class, track-layers and section hands on the railroad, and laborers in the factories and fields. What Southern California, or California generally, could do without them it is difficult to see. They seem, for the most part, capable, industrious, honest, and neat. One divests himself rapidly of the prejudice against

them with which he may have started. Let us hope that laborers of the better class, by whom they are to be succeeded, may at least have as many praiseworthy traits.

The town of Fresno is as yet chiefly a supply and market point for the numerous colonies by which it is environed. These colonies straggle out in various directions, beginning within a mile or two of the town. The intervening land still lies in its natural condition for settlement. It is difficult to convey an idea of its seemingly, hopeless barrenness. Instead of complaining of dry grass here one would be grateful for a blade of grass of any kind. The surface is as arid as that of a gravelled school-yard. It is even worse, for it is undermined with' holes of gophers, owls, jack-rabbits, and squirrels. To ride at any speed is certain to bring one to grief through the entangling of his horse's legs in these pitfalls. As the traveller passes there is a scampering on all sides. The gray squirrels speed for their holes with flying leaps, the jack-rabbits with kangaroo-like bounds. They run toward us, if they chance to have been absent from home in an opposite direction. Not one considers himself safe from our clearly malicious designs till he has dived headlong into his own proper tenement.

Here and there are tracts white with alkali. Flakes of this substance, at once bitter and salt to the taste, can be taken up in an almost pure condition. Elsewhere we pass through tracts of wild sunflower a tall weed, charming in flower, but now thoroughly desiccated, and rattling together like dry bones.

This description applies, for the greater part of the year, not only to Fresno, but in an almost equal degree to Bakersfield, Los Angeles, and nearly the whole of

Southern California. Without it the wonders which have been produced by human agency could not be un-

derstood. The face of nature in all this district was a blank sheet of paper. The cultivator had absolutely everything to do. He discovered on trial that he had a

soil of remarkable capacity, and, with the aid of water and the genial climate, he could draw from it whatever he pleased.

Water is the salvation of the waste places, and makes the desert blossom like the rose. One's respect for this pleasant element is, if possible, increased upon seeing what it is here capable of. It seems that, if used with sufficient art, it might almost draw a crop from cast-iron. The vegetation of Southern California is thoroughly artificial. It consists of a series of scattered plantations created by the use of water. In these the traveller finds his flowers, palms, vineyards, and orange groves, and, burying himself among them, like the ostrich with its head in the sand, he may refuse briefly to recognize that there is anything else; but, as a matter of fact, only a small beginning has been made. What has been done, however, is an earnest of what can be done. It is found that, as irrigation is practised, the land stores up part of the water, and less is needed each year. In wells, too, the water is found nearer the surface, proving that the soil acts as a natural reservoir. As time goes on, and canals and vegetation increase, no doubt important climatic changes may be looked for. In the end Southern California may be as different from what it is at present as can be imagined.

The several Fresno colonies for the most part join one another, and form a continuous belt of cultivation. On

entering their confines the change is most agreeable. Close along-side the desert, the home of the gopher and

jack-rabbit, only separated from it by a narrow ditch of running water, are lovely vineyards, orchards of choice

fruits, ornamental flowers and shrubs, avenues of shade-trees, fields of corn, and green pastures of the alfalfa, a

tall and strong clover, which gives half a dozen crops a year. Embowered among these are the homes of happy families, and large establishments for the drying of fruits and converting the munificent crops of grapes into wine. Many of the homes are as yet but modest wooden cottages. Others, of a better class, are of adobe, treated in an ornamental way, with piazzas and Gothic gables.

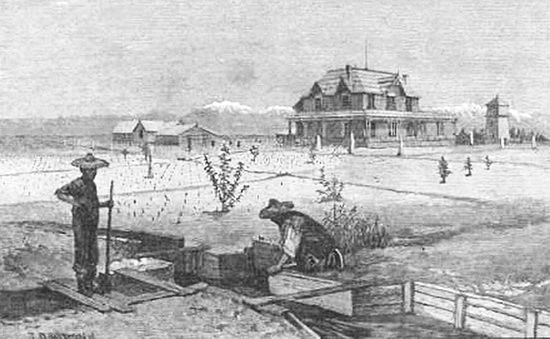

The most important residence is that of a late member of the San Francisco Stock Board, who has gone into the cultivation of grapes here on a large scale. It is a handsome villa that would do credit to any town. The improvements of the Barton place were in but an incipient state at the time of our visit. A great array of young vines brightened the recently sterile soil, but timidly and as if not quite certain of approval. Young orange and lemon trees in the door-yard were muffled in straw till they should have gained a greater hardihood to withstand the frosts. Elsewhere water was being run out from irrigating ditches over fields in preparation for the first time. It is the custom to soak them, in order that they may be perfectly levelled. Knolls or any other inequalities must not be left to hinder the equal distribution of water to the crop. A wide canal stretched back from the numerous out-buildings toward the horizon. On the verge of the wide plain showed the blue Sierras, veiled by a slight chronic dustiness of the atmosphere.

In the more established portions of the colonies some charming bits of landscape are found. The Chinese farm-hand wears a blue blouse and a wide basket-hat which he calls mow. He pronounces this hat "heap good" if complimented upon it. He prunes the vines or collects the generous clusters of grapes; or else he digs a vegetable

PRIVATE RESIDENCE AT FRESNO.

their banks. At Eisen's wine-making place, for a considerable distance, oleanders in flower are seen spaced between the trees. The water runs clear and swift. At Eisen's it turns a mill. No doubt devices for bathing in it might also be contrived if desired.

The long, symmetrical lines of trees have a foreign, or at least un-American, air. It is not difficult to recall to mind the mulberries and elms that bend over the irrigating canals of Northern Italy and drop their yellow leaves upon them in autumn like these. It might be Lombardy

again, and the glimpses of distant blue the Alps instead of the Sierras. The locks and gates for the water are of

an ephemeral structure as yet, made of planking instead of substantial brick and stone. The smaller ditches are often stopped with mere bits of board let down into grooves, instead of gates with handles. It is urged, however, that handles offer inducement to idlers to lift them up out of pure mischief, and waste the water. The colonies are not quite colonies in the usual sense; that is to say, they were not founded by persons who combined together and came at one and the same time. The lands they occupy were distributed into parcels by an original owner, and, after being provided with water facilities by an irrigation company, put upon the market at the disposal of whoever would buy. No doubt a certain general consistency rules them in keeping with the names

respectively set up, but it is not rigorous. Probably nothing need prevent a native American from joining the Scandinavian Colony, or a Scandinavian the American Colony, should he desire to do so.

As to the Temperance Colony, it must be sorely tried in a locality the most liberal and profitable yield of which

is the wine grape. It seems hardly a propitious place to have chosen. Scoffers say that in some instances while settlers will not make wine themselves they will sell their grapes to the wine-making establishments. This I merely note as "important, if true."

The standard twenty-acre lot, as prepared for market at Fresno, has its main irrigating ditch, of perhaps four feet in width, connecting with the general irrigating system. For twelve and a half dollars a year it receives a water-right entitling it to the use of whatever water it may need. The buyer must make his own minor ditches, and prepare his ground from this point. He usually aims to establish in his fields a number of slightly differing level, that the water may be led to one after the other. For ground in the preliminary condition described about fifty dollars per acre is demanded. Most of the earlier settlers bought for less, and the price named strikes one as high, considering the newness of the country, and the excellent farming land to be had in the older parts of the country for less. Prices are less here, however, than at Los Angeles, Riverside, or San Diego, farther south.

It is argued in answer to objectors that though land be not nominally it is really cheap, in consideration of its extraordinary productiveness. It is held that an investment here gives better returns than anywhere, and at the same

time that the climate and other conditions promise a more pleasurable existence than could be enjoyed elsewhere. This Fresno land, for instance, yields four and five crops

of alfalfa a year. Vineyards planted but two and a half years are shown which produce five tons of grapes to the

acre. Five years is the period required for the vines to come into full bearing. It is estimated that an acre of

vines in that condition will have cost one hundred and twenty-five dollars, allowing fifty dollars as the price of the ground, and it is then counted upon for an annual yield of ten tons of grapes, at twenty dollars a ton. The rate of growth in vegetation is one of the things to note. Fruit-trees are said to advance as far in three years as in seven on the Eastern sea-board.

The personal stories of the colonists are often interesting. They have generally had some previous hard experience of the world. Such a man, working sturdily in the field preparing the ground around a new cottage of his own, lost a fortune in the San Francisco Stock Board. The funds for his present enterprise were provided by his wife, who had turned to keeping boarders, and sent him her small profits monthly until he should have made ready a place for their joint occupancy. Instances were heard of where nice properties had been secured with no other original capital than a pair of brawny hands. These, however, were exceptional. The country appears to be one where it is most desirable for the new-comer to have a small capital.

In the Central Colony a comfortable estate was owned by four spinster school-teachers of San Francisco. They had combined to purchase eighty acres. One of them lived on the place and managed it. The others contributed from their earnings until it had reached a paying basis, passed only their vacations there at present, but looked forward to making it their ultimate retreat.

The idea seems both a praiseworthy new departure in the direction of female emancipation and charming in itself. I had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the resident manager of the experiment. Her experiences, written out, would, I think, be interesting and instructive. There was an open piano in the pleasant cottage interior, and late books and magazines were scattered about. It was a bit of refined civilization dropped down in the midst of the desert.

This lady had come, she said, for rest. She took pleasure, too, in the country, and in seeing things grow. She had made mistakes in her management at first, mainly through trusting too much to others, but now had things in good control. Four farm-hands—Chinamen—were employed. The eighty acres were distributed into vineyard, orchard, and alfalfa, about one-half devoted to the vineyard. Its product was turned, not into wine, but raisins. Apricots and nectarines had been found up to this time the most profitable orchard fruits. Almonds were less so, owing to the loss of time in husking them for market. There was among other crops a field of Egyptian corn, a variety which grows tall and slender, and runs up to a bushy head instead of forming ears. The sight of it carried one back to the Biblical story of Joseph and his brethren, and the picture-writing in the Pyramids.

The grapes for raisin-making are of the sweet Muscat variety. There was a "raisin-house" piled full of the flat boxes in which raisins are traditionally packed. The process of raisin-making is very simple. The bunches of grapes are cut from the vines, and laid in trays in the open fields. They are left there, properly turned at intervals, for a matter of a fortnight. There are neither rains nor dews to dampen them and delay the curing. Then they are removed to an airy building known as a "sweat-house," where they remain possibly a month, till the last vestiges of moisture are gone. Hence they go to be packed and shipped to market.

One must walk rather gingerly at present not to discern through the young and scattering plantations the bareness beyond, but in another ten years the scene can hardly fail to be one of rich luxuriance. The site is flat and prairie-like, and I should prefer, for in my part, to locate my earthly Paradise nearer the hills. Still, the taste of the time runs to earthly Paradises which are at the same time shrewd commercial ventures, and the cultivation of the plain is much easier than that of the slopes.