Mexico, as it was and as it is/Letter 16

LETTER XVI.

THE MUSEUM AND ITS ANTIQUITIES, CONTINUED.

Ascending by a broad flight of steps at the eastern end of the courtyard, you reach the second story of the University building, in which are the National Museum and the halls appropriated to students. On the ground floor, are a rather shabby and neglected chapel and the collegehall or recitation-room, the latter of which reminded me of some of the fine monastic chambers of the Old World, with their high ceilings, lofty windows, dark walls, carved pulpit, and oaken seats, brown with the hues of venerable age.

On the wall at the end of the first flight, as you ascend to the upper story, there is a huge picture, which covers the whole back of the building. It represents a court ceremony of the time of Charles IV.; and from the ugliness of the faces, and the characteristic mien of all the figures, there can be no doubt that it is a faithful representation, both of the persons and costume of the period depicted.

The first room you enter on your right, is a large hall which, like everything public I have yet seen in this Republic, is neglected and lumbered. Around the cornice hangs a row of the portraits of the Viceroys, in the stiff and formal guise of their several periods. Some are in military costume, some in monkish, some in civil, and some in the outlandish frills, furbelows and finery of the last century; but whether it be of wisdom, or of wickedness, nature has invariably stamped a decided character on every head.

In one corner of this apartment stand the remains of a throne, deposited among the rubbish as no longer valuable in a Republic. Near it, however, and in strange contrast, is placed the incomplete basso-relievo of a trophy of liberty; and above this, against the wall, in a rude coffin of rough pine boards, hangs a mummy, dug up not long ago on the fields of Tlaltelolco north of the city.

Yet this room is not altogether destitute of interest, if you can induce the keeper to open the shutters. The light then falls upon portraits of Ferdinand and Isabella at the end of the hall, which are worthy of the pencil of Velasquez.

Passing to the adjoining sala, we enter the Museum of Mexican Antiquities, and odd, indeed, is the jumble of fragments of the past and present that bursts upon your view.

In the centre of the room is a Castle and Fortification, made of wood and straw, with mimic guns and all the array of military power. This was the work of a poor prisoner—the labor of years of solitude and misery.

To the left is a numismatic cabinet, tolerably rich in Spanish specimens and in a collection of Roman coins, which promises, under the care of Mr. Gondra, to become exceedingly rare and valuable. Next, there is a small library of manuscripts of the early missionaries in Mexico; volumes of their sermons, poems, and records of marriages, births and baptisms soon after the conquest. It is astonishing to see how many took the name of Hernando Cortez. Next to this, again, is another case containing (among all sorts of antiquated gimcrackery,) some beautiful specimens of the rag and wax-work, which I described in a former letter. In a corner hard by, covered with dust, lie the original drawings of Palenque and the volumes of Lord Kingsborough's Mexico, presented to this Museum by that munificent antiquarian. They are rarely looked at, except by some foreign traveller who happens to straggle into the Museum.

The rest of the collection is valuable. In the adjoining cases are all the smaller Mexican Antiquities, which have been gathered together by the labor of many years, and arranged with some attention to system. In one department you find the hatchets used by the Indians; the ornaments of beads of obsidian and stone worn round their necks; the mirrors of obsidian; the masks of the same material, which they hung at different seasons before the faces of their idols; their bows and arrows and arrow-heads of obsidian, some of them so small and beautifully cut, that the smallest bird might be killed without injuring the plumage.

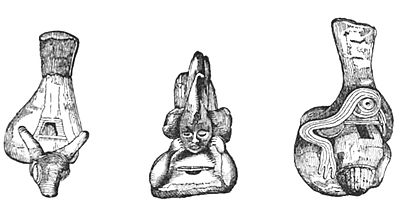

In another department are the smaller idols of the ancient Indians, in clay and stone, specimens of which, together with the small domestic altars and vases for burning incense, are exhibited in the following drawings:

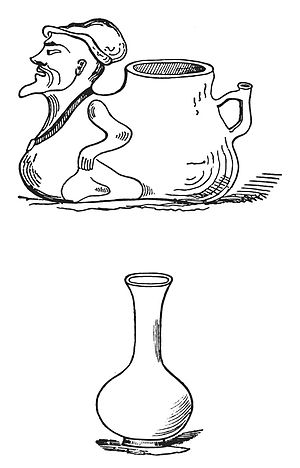

In the next case is a collection of Mexican Vases and Cups, most of which were discovered about the year 1827, in subterranean chambers, in the Island of Sacrificios.

Owing to the inertness of the Mexican Government, no thorough exploration has as yet been made, but it has been left to the enterprise of commanders of vessels, and especially of vessels of war, who, taking advantage of their detention at anchor under the lee of the island, have rummaged the sands in search of Indian remains, which have been carried to other lands, and are thus for ever lost to Mexico.

In 1841, Monsieur Dumanoir, who commanded the French corvette Ceres, undertook to explore the island. In the centre of it he discovered sepulchres, the bones in which were in admirable preservation; vases of clay, adorned with paintings and engraved; arms, idols, collars, bracelets, teeth of dogs and tigers, and a variety of architectural designs. In one place he found a vase of white marble; and in the Museum at Mexico there is now preserved another, also found at Sacrificios, of which the following is the classic shape and adornment:

I give the form of another vase found in this island, which, though neither beautiful nor classical as the one above represented, is remarkable for the oddness of its outline.

This vessel is also made of a white transparent marble.

In a neighboring cabinet is seen a curious little figure, carved in serpentine. It appears to have been a charm or talisman, and in many respects resembles the bronze figures which were found at Pompeii, and are preserved in the Secret Museum at Naples. This relic was discovered at St. Iago Tlaltelolco, immediately north of the city of Mexico; but the design appears to me too indelicate to be inserted in a work intended for general readers. It struck me as resembling the images used of old in the worship of Isis, and if it does not serve as a link in the supposed connection between the Egyptians and the Mexicans, it certainly exhibits as great a disregard for decency as characterized the great "mother of ancient art and civilization."

The figures Nos. 1 and 2, on the next page, are drawings of two Indian Axes or Hatchets, of stone, the first of which was discovered in Baltimore County, State of Maryland, and the second near St. Louis Potosi, in Mexico! I have contrasted them, as singularly alike in shape and material, both being grooved near the top for the purpose of fitting into a handle;—yet at what a distance from each other were they found![1]

The next cut represents a couple of Indian Pipes, the larger one of

which is finely glazed with red.

At the western end of this room are several models of Mines, chiefly made of the different stones found in the mineral regions of Mexico. The figures are of silver; and the various parts of the mine, the mode of obtaining the ore, of freeing them from water, of sinking shafts, the dresses, appearance and labors of the workmen, are most faithfully portrayed.

In one of the corners, behind a quantity of rubbish, old desks and benches, is the Armor of Cortéz—a plain unornamented suit of steel, from the size of which, I judge that the Conqueror was not a man of large frame or great bodily strength. Among the portraits of the Viceroys contained in this apartment, there is one of Cortéz; and in it he is depicted in a different manner from that in which we have been accustomed to know him since our boyhood, when we first made his acquaintance in school histories, drawn as a savage-looking hero with slouched hat and feather and fur-caped coat. There is no doubt, I am told, of the genuineness of the picture in this Museum; and its history is traced with certainty to the period of the third Viceroy, when the gallery of portraits was commenced. It represents him in armor, highly polished, and inlaid with. gold. One hand rests upon his plumed helmet and the other on a truncheon. The figure is slender and graceful. I should say, from the expression of the head alone, that the portrait was accurate. His eyes are raised to heaven—his gray hair curls around a rather narrow and not very lofty brow, and the lower part of his face is covered with a grizzly beard and mustache, through which appears a mouth marked with firmness and dignity. There is a look of the world, and of heaven; of veneration and authority. It is, in fact, a characteristic picture of the bigoted soldier, who slew thousands in the acquisition of gold, empire, and a new altar for the Holy Cross. Never was the biography of a hero and enthusiast, more fully written in history, than has been done by the unknown painter of this portrait on the canvas which embellished the walls of the Colonial Palace of Mexico.

In the same room with this picture, hangs the banner under which he conquered. It is in a large gold frame, covered with glass; and, as well as I could distinguish in the bad light in which it is placed, represents the Virgin Mary, painted on crimson silk, surrounded with stars and an inscription.

Just below this is an old Indian painting, made shortly after the conquest, of which the following engraving is a facsimile. I copied it very carefully, as an authentic record of some of the cruelties practiced by the Spaniards in subduing the chiefs of the country, and striking terror to the minds of the artless Indians.

The two figures in the left-hand corner are Cortez and Doña Marina as the mottoes above indicate. Marina holds a rosary in her hand, while the Marquis appears to be in the act of speaking and perhaps giving order for the execution represented beneath, where a Spaniard is seen in the act of loosening a blood-hound, who springs at the throat of an Indian. In the original copy all the colors are given. The hair of the victim is erect with horror, his eyes and mouth are distended, and his throat is spotted with blood, as the fangs and claws of the ferocious beast are driven through his flesh.

Aptly placed just below this curious picture is another of the last of the Kings of Tezcoco, of which I shall have occasion to speak hereafter; and beneath that again, on a stand, in the midst of a number of hideous idols carved in stone, are two Funeral Vases of baked clay, found some years since at St. Jago Tlatelolco, the northern suburb of the city.

Funeral Vase With Cover.

This vase, besides being remarkable for the ornaments in relief upon it, presents all the colors with which it was originally painted, in high preservation and brilliancy. Immediately below the rim is a winged head with an Indian dress of plumes. The eyes are wide and fixed, and the mouth is partly opened, displaying the teeth. The handles are oddly shaped, and depending from the tips of the wings is a collar formed of alternate ears of corn and sunflowers. The colors of the body of this vase are a bright azure; the upper rim is a brilliant crimson, and the next a light-pink. The head and the ends of the wings, with the stripe in the middle, are painted a light-brown. The circular ornament in the centre is crimson, and the figures on it yellow. The sunflowers are also yellow, while the two outer ears of corn are red, and the centre one blue. The band below these is brown, similar to the head and wings.

The head on this vase is very remarkable in its expression. There is a fixed, intense, stony stare in the eyes, and a pinched sharpness about the mouth, which denote its character. It was evidently the idea of an Angel of death, while the full blown sunflower, and the ripe and stripped ears of corn, denote the fullness of years.

In one of the cases are a series of interesting objects, of which the following designs will give the reader some idea.

This is a rattle, made of baked clay, finely tempered, containing a small ball, the size of a pea.

The next figures are specimens of "household gods;" some of the originals of which are now in my possession.

Like the ancient Romans, the Mexicans had their Penates, called by them Tepitoton. The sovereigns, and great lords always had six of them in their dwellings; the nobles four, and the common people two; and it is related by Clavigero, that these gods were to be found everywhere in their streets.

In this manner, the immense number of clay figures and fragments which are constantly dug up in every excavation made in the city of Mexico and its neighborhood, is satisfactorily accounted for.

Besides the rattle, given before, there are remains, or traditions, of but few other musical instruments known to the Mexicans. The Teponaztli or Indian drum, is made of hollowed wood, the exterior being covered with tasteful carving, of which the following designs will convey a

faithful idea.

These are the whistles, made of baked clay, and covered with grotesque figures in relief.

The last figures represent flageolets, made, like the whistles, of baked clay. They have four stops, and the sound is, of course, very monotonous. I have seen them used, even at the present day, in some religious ceremonials of the Indians, as an accompaniment to a drum which, though not

shaped like the teponaxth, produced quite as little music.

******

Around the walls of this chamber of the Museum are hung old Indian paintings of portions of Mexican history; genealogies of the Mexican monarchs; computations of time; plans of the city before the conquest, and pictures of various battles and skirmishes that occurred between the

natives and the invaders. I regret to say that many of these are only copies, the originals having been taken to England shortly after the establishment of Independence, whence they have never been returned. They are placed better there, perhaps, than they would be in Mexico; where the

existing remains of antiquity excite no curiosity, and lie, from year to year, covered with dust, and unexplored on the walls and in the closets of a university. With the exception of Don Carlos Bustamante, I know no one who has devoted an hour, of late years, to these interesting studies;

and the curator of the Museum, Don Isidrio Gondra, is so continually occupied with his political duties, in the editing of the Government Gazette, and lacks so greatly the encouragement of the Government, and its dedication of even a thousand dollars a year to archaeological researches, that he does no more than open the doors of these saloons on stated days and smoke his cigar quietly in a corner; while the ladies, gentlemen, loafers and léperos, wander from case to case, and lift up their hands in astonishment at the grotesque forms.

What those forms and figures mean; what was represented by such an idol, or what by another—receives the unfailing Mexican answer: "Quien sabe?"—"who knows? who can tell?"

But I must not leave this building, without some remarks on a vase, of which the sketch of the next page is an accurate drawing, representing both its sides.

I have desired to place it before you for the purpose of comparing the figures engraved on it with the style of the figures drawn by Mr. Catherwood, in Mr. Stephens's travels in Yucatan and elsewhere. Although there are no figures to which I can at once and entirely assimilate these, yet there is a general resemblance which cannot fail to strike the most careless observer.

It will be recollected that Tula was the head-quarters, at one period, of the tribes which afterward penetrated into the Valley of Mexico, and some of which even continued still farther to the southward. May they not have been the parent stock from which sprang the builders of the numerous cities which now lie in ruins in Yucatan? And may not this vase serve to show a connection between all the people who, at the time of the conquest, dwelt on the narrow land which connects the Northern and the Southern portions of our Continent?

I recollect very well, with how much gusto Mr. Gondra brought it forth for my inspection, after he had seen the designs of Mr. Catherwood, and how perfectly his mind seems to be satisfied of the identity and character, origin and habits, of the people who formed this vessel and reared the Temples of Palenque.

******

Beyond the room in which we have been so long detained, there is still another apartment, devoted to Natural History. But the Present fares no better than the Past. The birds and beasts are badly stuffed, badly mounted, badly arranged; and when I hoped to find a collection of minerals, or, at least some rare specimens of the splendid ores of Mexico, systematically arranged, I regret to say that I met with equal disappointment.

The last time I visited the Museum, I found on the centre table of the saloon of antiquities, the armor of Alvarado. It was pleasant to know that it had at length reached so appropriate a destination, after having been hawked about the Capital by various brokers, who were at one period on the eve of selling it to me, together with the hero's commission, signed by the Emperor, for the sum of one hundred dollars! The Government gave one hundred and forty dollars for them, or I have no doubt that these relics of one of the bravest of the conquerors, and the next in repute to Cortéz, would now adorn the walls of our National Institute.

Teotaomique—profile.

Teotaomique—front.

- ↑ Axes of this shape and material have been found in many of our States. For an interesting notice of them, vide Belknap's History of New Hampshire. vol. 3rd, p, 89. "The hatchet" says this writer, "is a hard stone, eight or ten inches in length and three or four in breadth, of an oval form, flatted and rubbed to as edge at one end: near the other is a grove, in which the handle was fastened, and their process to do it was this: When the stone was prepared, they chose a very young sapling, and splitting it near the ground, they forced the hatchet into it as far as the grove, and left nature to complete the work by the growth of the wood, so as to fill the grove and adhere firmly to the stone. Then they cut the sapling above and below, and the hatchet is fit for use.'