Mexico, as it was and as it is/Letter 27

LETTER XXVII.

DESAGUA. CARRIAGES. MULES. TROOPS. MUSIC. OPERA. RECRUITS.

THEATRES. MEXICAN THIEVES. THE JUDGE AND TURKEY.

Mexico, lying in the lap of a valley, with mountains around it continually pouring their streams into the sandy soil, has been frequently in danger of returning to the "slime from whence she rose." Since the trees have been cut from the plains and the surface exposed to the direct action of the sun, the valley has become drier and the lake has shrunk; but Mexico has, nevertheless, been several times threatened with inundations.

In estimating the dangerous situation of the Metropolis, it is necessary for you to recollect the position and levels of the adjacent lakes. Southeastwardly is the lake of Chalco; northwestwardly the lake of Tezcoco; and north of that again, in a continuous chain, are the lakes of San Cristoval and Zumpango. The latter sheet of water is about eighteen feet higher than San Cristoval,—San Cristoval is twelve feet higher than Tezcoco,—and the level of the great Square of Mexico is not more than three feet above that of Tezcoco. Thus, the head of water which could be easily poured over the Capital is immense, especially as the river Cuautitian pours an additional stream constantly into the northern link of the chain at Zumpango. In 1629 the whole city of Mexico, with the exception of the Plaza, was laid waste by inundation. In most of the streets the water continued for upward of three years, and, until 1634, portions of the town were still traversed by canoes.

So great was the misery and want caused by this misfortune, that the Court of Spain had issued orders to abandon the Capital and build a new one, between Tacuba and Tacubaya, on upland levels, that had never been reached by the lakes before the conquest. An earthquake, however, rent the earth and freed the city of the accumulated waters; and the result of this warning was the completion of an immense Desagua or sewer, which thoroughly empties the ordinary contents of the valley. But urgent as was the necessity for this work, it was procrastinated by the dilatoriness of Mexican laborers, until the year 1789. "The whole length of the cut," is said by Mr. Ward, "to be, from the sluice called Vertideros, to the salto of the river Tula, 67,537 feet; where the waters are discharged at a spot about 300 feet beneath the level of the lake of

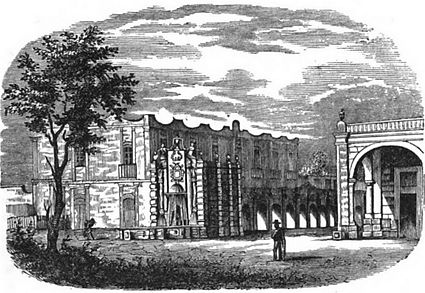

termination of an aqueduct in mexico

This Desague, and the noble aqueducts by which the city is supplied, are the only very great enterprises, of this character, in the country; and they are all owing to the energy of the old Spanish government, which emulated the magnificence of the Romans in its public improvments, connected with elegance and comfort. During the royal sway the roads, also, were properly made and repaired; but since the Revolution, when most of them were torn up to prevent the passage of troops, or destroyed by the transit of artillery, they have been abandoned to the weather and travel, so that in fact, (with the exception of the highway to Vera Cruz, which has recently been improved,) there is scarcely a road in the Republic that does not resemble more the deserted bed of a mountain stream, than a work intended to facilitate communication. The idea of " internal improvements" has never entered into the calculation of these people;—though, some years since, a scheme was set on foot to construct a railway from the coast to the Capital, and its practicability proved by a scientific recornoissance. Adventures of this character will be the first evidences of the growth of mind among the masses in Mexico, when they are taught to believe that they have other sources of wealth besides mines, and that riches do not consist alone In gold and silver. Until that period, the patient and toilsome mule will continue to be the means of transportation of the chief burdens from the sea to the interior.

If we suppose it to be perfectly practicable to make a railway of about 350 miles in length, with all its sinuosities, from Vera Cruz to the Capital, I think the following estimate may be reasonably made of the profits of such an enterprise; especially, when it is recollected that the distance will be passed in less than 24 hours, instead of four days, (as at present in the diligence,) and from eighteen to twenty-five days, by mules and wagons.

| Cost of Railway, say | $6,000,000 |

| Motive power,cars, &c. | 200,000 |

| Contingent expenses | 300,000 |

| $6,500,000 | |

| The interest of which, per annum, at 6 per cent. Will be | $ 390,000 |

It may be estimated, that about fifty thousand tons are imported annually into Vera Cruz. A ton weight is transported usually on about seven mules, each mule load being worth $25, from Vera Cruz to Mexico.

Fifty thousand tons will then cost for transportation $8,750,000. But suppose we take only the half, or twenty-five thousand tons to be transported to the interior, and we shall have for the cost, $4,875,000, for the annual value of mule freight.

I think it would be perfectly fair to consider this sum as the income of a railway, (at least, during the first years of the enterprise,) especially when the transportation of passengers and the speed with which merchants will he served with their goods, are taken into consideration as inducements.

The statement of freights which I have made above, is only of carriage to the Capital; an equal sum, nearly, may be expected to cover the transportation from it, including passengers, and pay for the portage of coin and bullion to the coast. But, if nothing more than $4,375,000, in all, are raised as income, you will perceive that the road must pay for itself in less than two years, or yield (after deducting expenses,) more than thirty per cent, to its shareholders. If the low cost of the railway is objected to, let the estimate be doubled, and still the profits will be proportionably great, if we take into account the extension of business that will be created by the increase of facilities.

I think it may be safely stated, that two thousand passengers pass over the road every year between Vera Cruz and Mexico, each paying $50 for his seat, or, $100,000 in all. How great would be the increase of travelling—the security of life and property from robbers— the inducements to trade—and the general promotion of the prosperity of the Republic, by an outlay of money at so profitable an interest![1]

MEXICAN COACHES AND MULES.

Not the least singular of the sights of the Metropolis, are the mules harnassed to the antique vehicles still used by some of the old fashioned folks of Mexico. The carriage is usually quite globular, or tun-like, with its doors and sides covered with elaborate gilding and painting. This clumsy cavity is suspended on a carved and gaudy-colored framework, or square scaffolding, resting on enormous wheels; and the whole machine has the appearance of a big fly hanging in the midst of a spider-web. A long pole extends in front, to which are attached a pair of mules, almost hidden in a heavy harness studded with brass bosses and shining ornaments, while the tails of the luckless animals are invariably stuck into leathern bags by way of queue! A postillion, with short jacket, of brown stamped leather, embroidered with green braid; stout leggings, spurs with two-inch rowels; broad-brimmed hat, and whip of sounding thong, bestrides one of the beasts; and the whole apparatus moves off with a slow lumbering pace, that resembles in motion and appearance nothing that I can now recollect, but one of those old-fashioned wooden houses, that, in times long past, we used to see removed from street to street, until they disappeared in the suburbs.

Even the riding horses of the Mexicans are not yet freed from the ancient lumber and trappings with which their ancestors covered them. At page 163, you will find a picture of a Mexican horseman, and observe that the animal's haunches are covered with a sort of hemisphere of leather terminated by an iron fringe, that jingles with every movement. This cumbrous hide was originally designed, at the period of the conquest, as an armor for the protection of the horse from Indian arrows, while the guard was continued in front of the beast by a similar apron that shielded his neck and throat. But now, although there are no more assailants of the peaceful riders, you may still frequently observe this uncouth covering on the finest animals; and the apology for the usage is, that by continually striking on a certain part of his hind legs with the lower fringe of iron, the horse is forced into a short, ambling trot, which is held to be the summum bonum of Mexican comfort in the saddle. I confess, that I saw no beauty in the mincing gate which is thus acquired, especially as the animal most celebrated for it in Mexico scarcely advanced a dozen yards in a minute, while, from the amount of exercise he appeared to be taking, and the incessant pawing of his feet and chafing of his bit, an observer would be induced to believe he was advancing at a furious pace. It is one of those capricious luxuries to which men resort, when they have exhausted the round of natural and simple tastes.

I have forgotten to say anything to you hitherto of the parades of troops, for which this Capital is in some degree famous. As I profess to have no military knowledge, you must not expect a very critical account of their appearance or manœuvres; but I have seldom seen better looking regiments in Europe than the 11th Infantry, under the command of Lombardini. The uniform is white, like the Austrian, and is kept in excellent order. The arms are clean and bright, and the officers of division appear to be well trained, and to have imparted their training to the men. On the 13th of June 1842, about eight thousand of these troops were brought together, to be reviewed by General Santa Anna, on the meadows south of the city. In line they had an extremely martial bearing, and, so far as I was able to judge of their skill, the sham-fight that took place afterward was admirably executed. Excellent and daring riders, as are all the Mexicans, they must ever have a decided advantage in their cavalry; and, although they do not present so splendid an appearance in equipments as some of the other regiments, I have no doubt they constitute the most effective arm of the Mexican service. Indeed, almost all the foreigners and even Texans, with whom I have spoken in regard to the qualities of these men, concur in a high estimate of the Mexican soldier, although they do not think so well of the Mexican officer. This in all probability, arises from the irregular manner in which persons arrive at command and the want of soldierlike education and discipline. Officers have been, most frequently, taken at once from private life or pursuits by no means warlike, and found themselves suddenly at the head of troops, without a knowledge of their duties, either in the barrack, camp, or field, or a due estimate of the virtues of obedience, and that disciplined courage arising from a perfect self-reliance in every emergency. The result of this unfortunate state of things has been, that, in conflicts with the Texans, while the men have often appeared anxious to fight, they lacked officers who were willing to lead them into the thick of the mêlée.

You can fancy nothing more odd, than the manner in which this army is recruited. A number of men are perhaps wanted to complete a new company, and a sergeant with his guard is forthwith dispatched to inspect the neighboring Indians and Meztizos. The subaltern finds a dozen or more at work in the fields; and, without even the formality of a request, immediately picks his men and orders them into the ranks. If they attempt to escape or resist, they are at once lassoed; and, at nightfall, the whole gang is marched, tied in pairs, into the cuartel of the village or the guardroom of the Palace, with a long and lugubrious procession of wives and children, weeping and howling for the loss of their martial mates. Next day the "volunteers" are handed over to the drill-sergeant; and I have often laughed most heartily at the singular group presented by these new-caught soldiers, on their first parade under their military tutor. One half of their number are always Indians, and the rest, most likely, léperos. One has a pair of trowsers, but no shirt; another a shirt and a pair of drawers; another hides himself, as well as he can, under his blanket and broad-rimmed hat; another has drawers and a military cap. But the most ridiculous looking object I remember to have seen in Mexico, was a fat and greasy lépero, who had managed to possess himself of a pair of trowsers that just reached his hips, and were kept up by a strap around his loins, together with an old uniform coat a great deal too short for him both in the sleeves and on the front. As he was not lucky enough to own a shirt, a vast continent of brown stomach lay shining in the sun between the unsociable garments! He held his head, which was supported by a tall stock, higher than any man in the squad, and marched magnificently—especially in "lock step!"

The drilling of these men is constant and severe. The sergeant is generally a well-trained soldier, and unsparing in the use of his long hard rod for the slightest symptom of neglect. In a few weeks, after the new troops acquire the ordinary routine of duty, they are put into uniform, paraded through the streets, and you would scarcely believe they ever had been the coarse Indians, and scurvy léperos, who robbed you on the road or pilfered your pockets in the streets.

It would be improper, in speaking of the Mexican military, not to notice, especially, their excellent bands of music. The Spaniards transplanted their love and taste for this beautiful science to Mexico. The Indians have caught the spirit from their task-masters;—and whether it be in the tinkling guitar or the swelling harmonies of a united corps, you can scarce go wrong, in expecting an exhibition of the art from a native. It is the custom for one of the regimental bands to meet after sundown, under the windows of the Palace, in the Plaza, which is filled with an attentive crowd of eager listeners to the choicest airs of modern composers.

I have said, that this musical taste pervades all classes; and it was, therefore, to be hoped, that a regularly established Operatic corps would have readily succeeded in the Capital. But from a variety of causes the experiment failed. The Revolution of 1841, interfered with it at the outset, in the months of August and September; and, from the unfavorable location of the house, and other circumstances, the whole enterprise was visited with a series of disastrous losses that left the management, in July, 1842, with a deficit of upward of 32,000 dollars. The singers were good; the prima donna (Madame Castellan,) and basso, unexceptionable; but the establishment never became fashionable.

Not so, however, with the Theatres;—three of which were almost constantly in operation while I resided in Mexico. The "Principal," the resort of the old aristocracy, was the theatre of staid fashion;—the "Nuevo Mexico," a haunt of the newer people, who looked down on the "legitimate drama," and tolerated the excitement of innovation and novelty;—and the "Puente Quebrada," a species of San Carlino, where "the people" revelled in the coarser jokes and broader scenes of an ad libitum performance.

I frequently visited the Principal, but kept a box with several young friends at the Nuevo Mexico, where I found the greatest advantage in the study of the Spanish language, from the excellent recitations of the "comicos." Most of them were Castillians, who spoke their native tongue with all the distinctive niceties of pronunciation, besides producing all the newest efforts of the Spanish muse.

It was singular to observe, how from a small beginning and really excellent performances, the taste and wealth of Mexico was gradually drawn from its old loves at the Principal to the daring upstart. I have elsewhere told you that the theatre is a Mexican necessary of life. It is the legitimate conclusion of a day, and all go to it;—the old, because they have been accustomed to do so from their infancy; the middle aged, because they find it difficult to spend their time otherwise; and the young for a thousand reasons which the young will most readily understand.

The boxes are usually let by the month or year, and are, of course, the resort of families who fill them in full dress every evening, and use them as a receiving-room for the habitués of their houses; although it is not so much the custom to visit in the theatre as in Italy.

The pit is the paradise of bachelors. Its seats are arm-chairs, rented by the month, and of course never occupied but by their regular owners. The stage is large, and the scenery well painted; but the whole performance becomes rather a sort of mere repetition than acting, as the "comicos" invariably follow the words, uttered in quite a loud tone by a prompter, who sits in front beneath the stage with his head only partially concealed by a wooden hood. A constant reliance on this person, greatly impairs the dramatic effect, and makes the whole little better than bad reading; but I was glad to perceive that the actors of Nuevo Mexico had evidently studied their parts, and really performed the characters of the best dramas of the Spanish school.

I cannot but think this habitual domestication at the theatre, is injurious to the habits of the Mexicans. It makes their women live too much abroad, and cultivates a love of admiration. The dull, dawdling morning at home, is succeeded by an evening drive; and that, again, by the customary seat at the Opera or Play-house, where they listen to repetitions of the same pieces, flirt with the same cavaliers, or play the graceful with their fans. If the entertainments were of a highly intellectual character, or a development of the loftier passions of the soul, (as in the master-pieces of our English school,) there would be some excuse for an indulgence of this national taste; but the disposition of the audiences is chiefly directed, either toward comedy, or to a vapid melodrama in the most prurient style of the modern French. Love and murder,—crime and wickedness,—have converted the stage into a dramatic Newgate, where sentimental felons and beautiful females, whose morality is as questionable as the color of their cheeks, are made by turns to excite our wonder and disgust.

MEXICAN ROGUERY.

When giving you an account, the other day, of Mexican prisons and prisoners, I forgot to relate some anecdotes that are told in the Capital of the adroitness of native thievery.

Some time since, an English gentleman was quietly sauntering along the Portales—the most crowded thoroughfare of Mexico—his attention being occupied with the variety of wares offered for sale by the small dealers;—when, suddenly, he felt his hat gently lifted from his head. Before he could turn to seize the thief, the rascal was already a dozen yards distant, dodging through the crowd.

Upon another occasion, a Mexican was stopped in broad daylight, in a lonely part of the town, by three men, who demanded his cloak. Of course, he very strongly objected to parting with so valuable an article; when two of them placed themselves on either side of him, and the third, seizing the garment, immediately disappeared, leaving the victim in the grip of his companions.

His cloak gone, he naturally imagined that the thieves had no further use for him, and attempted to depart. The vagabonds, however, told him to remain patiently where he was, and he would find the result more agreeable than he expected.

In the course of fifleen minutes their accomplice returned, and politely bowing, handed the gentleman a pawnbroker's ticket!

"We wanted thirty dollars, and not the cloak," said the villain; "here is a ticket, with which you may redeem it for that sum, and as the cloak of such a Caballero is unquestionably worth at least a hundred dollars, you may consider yourself as having made seventy by the transaction! Vaya con Dios!"

A third instance of prigging, is worthy the particular attention of the London swell mob; and I question if it has been surpassed in adroitness, for some time past, in that notorious city, where boys are regularly taught the science of thieving, from the simple pilfer of a handkerchief, to the compound abstraction of a gold watch and guard-chain.

A TALE OF A TURKEY.

As a certain learned Judge in Mexico, some time since, walked one morning into Court, he thought he would examine whether he was in time for business; and, feeling for his repeater—found it was not in his pocket.

"As usual," said he to a friend who accompanied him, as he passed through the crowd near the door—"As usual, I have again left my watch at home under my pillow."

He went on the bench and thought no more of it. The Court adjourned and he returned home. As soon as he was quietly seated in his parlor, be bethought him of his timepiece, and turning to his wife, requested her to send for it to their chamber.

"But, my dear Judge," said she, "I sent it to you three hours ago!"

"Sent it to me, my love? Certainly not."

"Unquestionably," replied the lady, "and by the person you sent for it!"

"The person I sent for it!" echoed the Judge.

“Precisely, my dear, the very person you sent for it! You had not left home more than an hour, when a well-dressed man knocked at the door and asked to see me. He brought one of the very finest turkies I eyer saw, and said, that on your way to Court you met an indian with a number of fowls, and having bought this one, quite a bargain, you had given him a couple of reals to bring it home; with the request that I would have it killed, picked, and put to cool, as you intended to invite your brother judges to a dish of mollé with you to-morrow. And, ‘Oh! by the way, Señora,’ said he, 'his Excellency, the Judge, requested me to ask you to give yourself the trouble to go to your chamber and take his watch from under the pillow, where he says he left it, as usual, this morning, and send it to him by me.' And, of course, mi querido, I did so."

“You did?" said the Judge.

“Certainly," said the lady.

“Well," replied his Honor, “all I can say to you, my dear, is, that you are as great a goose, as the bird is a turkey. You've been robbed, madam;—the man was a thief;—I never sent for my watch;—you've been imposed on;—and, as a necessary consequence, the confounded watch is lost for ever!"

The trick was a cunning one; and after a laugh, and the restoration of the Judge's good-humor by a good meal, it was resolved actually to have the turkey for to-morrow's dinner, and his Honor's brothers of the bench to enjoy so dear a morsel.

Accordingly, after the adjournment of Court next day, they all repaired to his dwelling, with appetites sharpened by the expectation of a rare repast.

Scarcely had they entered the sala and exchanged the ordinary salutations, when the lady broke forth with congratulations to his Honor upon the recovery of his stolen watch!

"How happy am I," exclaimed she, "that the villain was apprehended!"

"Apprehended!" said the Judge, with surprise.

“Yes; and doubtless convicted, too, by this time," said his wife.

“You are always talking riddles," replied he. "Explain yourself, my dear. I know nothing of thief, watch, or conviction."

" It can't be possible that I have been again deceived," quoth the lady, “but listen:— “About one o'clock to-day, a pale, and rather interesting young gentleman, dressed in a seedy suit of black, came to the house in great haste— almost out of breath. He said that he was just from Court;—that he was one of the clerks;—that the great villain who had the audacity to steal your Honor's watch had just been arrested;—that the evidence was nearly perfect to convict him;—and all that was required to complete it was ’the turkey,’ which must be brought into Court, and for that he had been sent with a porter by your express orders."

“And you gave it him!"

"Of course I did—who could have doubted or resisted the orders of a Judge!

"Watch—and turkey—both gone! pray, what the devil, madam, are we to do for a dinner?"

But the lady had taken care of her guests, notwithstanding her simplicity and the party enjoyed both the joke and their viands.

- ↑ Since the above was written, I learned that the Government has issued orders for the repair and improvements of roads all over the Republic. An enterprise has been set on foot by Mexican merchants of great wealth and respectability, to open a communication with the Pacific, across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, partly by railway.

The railway from Vera Cruz to the River San Juan, in the direction of Jalapa, has been commenced, and laborers are already at work on four miles of the twenty-one of which it consist.