Mr. Punch's History of the Great War/Prologue

PROLOGUE

THOUGH a lover of peace, Mr. Punch from his earliest days has not been unfamiliar with war. He was born during the Afghan campaign; in his youth England fought side by side with the French in the Crimea; he saw the old Queen bestow the first Victoria Crosses in 1857; he was moved and stirred by the horrors and heroisms of the Indian Mutiny. A little later on, when our relations with France were strained by the Imperialism of Louis Napoleon, he had witnessed the rise of the volunteer movement and made merry with the activities of the citizen soldier of Brook Green. Later on again he had watched, not without grave misgiving, the growth of the great Prussian war machine which crushed Denmark, overthrew Austria, and having isolated France, overwhelmed her heroic resistance by superior numbers and science, and stripped her of Alsace-Lorraine.

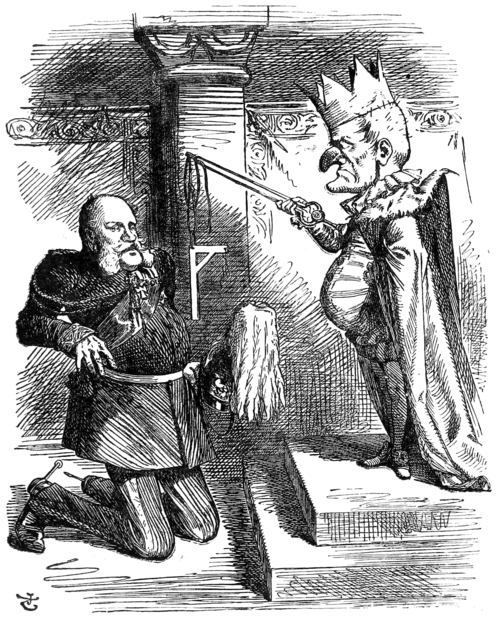

In May, 1864, Mr. Punch presented the King of Prussia with the "Order of St. Gibbet" for his treatment of Denmark.

In August of the same year he portrayed the brigands dividing the spoil and Prussia grabbing the lion's share, thus foreshadowing the inevitable conflict with Austria.

In the war of 1870–1 he showed France on her knees but defying the new Cæsar, and arraigned Bismarck before the altar of Justice for demanding exorbitant securities.

And in 1873, when the German occupation was ended by the payment of the indemnity, in a flash of prophetic vision Mr. Punch pictured France, vanquished but unsubdued, bidding her conqueror "Au revoir."

More than forty years followed, years of peace and prosperity for Great Britain, only broken by the South African war, the wounds of which were healed by a generous settlement. But all the time Germany was preparing for "The Day," steadily perfecting her war machine, enlarging her armies, creating a great fleet, and piling up colossal supplies of guns and munitions, while her professors and historians, harnessed to the car of militarism, inflamed the people against England as the jealous enemy of Germany's legitimate expansion. Abroad, like a great octopus, she was fastening the tentacles

of permeation and penetration in every corner of the globe, honeycombing Russia and Belgium, France, England and America with secret agents, spying and intriguing and abusing our hospitality. For twenty-five years the Kaiser was our frequent and honoured, if somewhat embarrassing, guest, professing friendship for England and admiration of her ways, shooting at Sandringham, competing at Cowes, sending telegrams of congratulation to the University boat-race winners, ingratiating himself with all he met by his social gifts, his vivacious conversation, his prodigious versatility and energy.

Mr. Punch was no enemy of Germany. He remembered—none better—the debt we owe to her learning and her art; to Bach and Beethoven, to Handel, the "dear Saxon" who adopted our citizenship; to Mendelssohn, who regarded England as his second home; to her fairy tales and folk-lore; to the Brothers Grimm and the Struwwelpeter; to the old kindly Germany which has been driven mad by War Lords and PanGermans. If Mr. Punch's awakening was gradual he at least recognised the dangerous elements in the Kaiser's character as far back as October, 1888, when he underlined Bismarck's warning against Cæsarism. In March, 1890, appeared Tenniel's famous cartoon "Dropping the Pilot"; in May of the same year the Kaiser appears as the Enfant Terrible of Europe, rocking the boat and alarming his fellow-rulers. In January, 1892, he is the Imperial Jack-in-the-Box with a finger in every pie; in March, 1892, the modern Alexander, who

Assumes the God,

Affects to nod,

And seems to shake the spheres;

though unfortunately never nodding in the way that Homer did. (This cartoon, by the way, caused Punch to be excluded for a while from the Imperial Palace.)

In February, 1896, Mr. Punch drew the Kaiser as Fidgety Will. In January, 1897, he was the Imperial actor-manager casting himself for a leading part in Un Voyage en Chine; in October of the same year he was "Cook's Crusader," sympathising with the Turk at the time of the Cretan ultimatum; and in April, 1903, the famous visit to Tangier suggested the Moor of Potsdam wooing Morocco to the strains of

"Unter den Linden"—always at Home,

"Under the Limelight," wherever I roam.

"AU REVOIR!"

Germany: "Farewell, Madam, and if "

France: "Ha! We shall meet again!"

(Sept. 27, 1873)

In 1905 the Kaiser was "The Sower of Tares," the enemy of Europe.

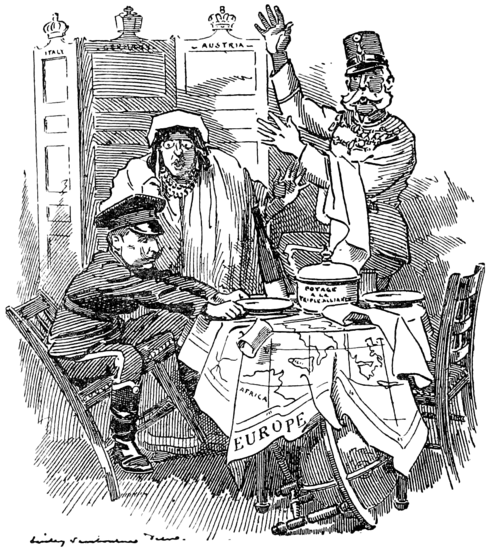

In 1910 he was Teutonising and Prussifying Turkey; in 1911 discovering to his discomfort that the Triple Entente was a solid fact.

And in September, 1913, he was shown as unable to

THE STORY OF FIDGETY WILHELM

(Up-to-date Version of "Struwwelpeter")

|

"Let me see if Wilhelm can Feb. 1, 1896.

|

"But Fidgety Will |

dissemble his disappointment at the defeat of the German-trained Turkish army by the Balkan League.

had "backed the wrong horse," culminating in the cartoon "Armageddon: a Diversion" in December, 1912, when Turkey says "Good! If only all these other Christian nations get at one another's throats I may have a dog's chance yet." Throughout the entire series the Sick Man remains cynical and impenitent, blowing endless bubble-promises of reform

from his hookah, bullying and massacring his subject races whenever he had the chance, playing off the jealousies of the Powers, one against the other, to further his own sinister ends.

Yet Mr. Punch does not wish to lay claim to any special prescience or wisdom, for, in spite of lucid intervals of foresight, we were all deceived by Germany. Nearly fifty years of peace had blinded us to fifty years of relentless preparation for war. But if we were deceived by the treachery of Germany's false professions, we had no monopoly of illusion. Germany made the huge mistake of believing that we would stand out—that we dared not support France in face of our troubles and divisions at home. She counted on the pacific influences in a Liberal Cabinet, on the looseness of the ties which bound us to our Dominions, on the "contemptible" numbers of our Expeditionary Force, on the surrender of Belgium. She had willed the War; the tragedy of Sarajevo gave her the excuse. There is no longer any need to fix the responsibility. The roots of the world conflict which seemed obscure to a neutral statesman have long been laid bare by the avowals of the chief criminal. The story is told in the Memoir of Prince Lichnowsky, in the revelations of Dr. Muehlon of Krupp's, in the official correspondence that has come to light since the Revolution of Berlin. Germany stands before the bar of civilisation as the reus confitens in the cause of light against darkness, freedom against world enslavement.

So the War began, and if "when war begins then hell opens," the saying gained a tenfold truth in the greatest War of all, when the aggressor at once began to wage it on noncombatants, on the helpless and innocent, on women and children, with a cold and deliberate ferocity unparalleled in history. Let it now be frankly owned that in the shock of this discovery Mr. Punch thought seriously of putting up his shutters. How could he carry on in a shattered and mourning world? The chronicle that follows shows how it became possible, thanks to the temper of all our people in all parts of the Empire, above all to the unwavering confidence of our sailors and soldiers, to that "wonderful spirit of light-heartedness, that perpetual sense of the ridiculous" which, in the words of one of Mr. Punch's many contributors from the front, "even under the most appalling conditions never seemed to desert them, and which indeed seemed to flourish more freely in the mud and rain of the front line trenches than in the comparative comfort of billets or 'cushy jobs.'" Tommy gave Mr. Punch his cue, and his high example was not thrown away on those at home, where, when all allowance is made for shirkers and slackers and scaremongers, callous pleasure-seekers, faint-hearted pacificists, rebels and traitors, the great majority so bore themselves as to convince Mr. Punch that it was not only a privilege but a duty to minister to mirth even at times when one hastened to laugh for fear of being obliged to weep. In this resolve he was fortified and encouraged, week after week, by the generous recognition of his efforts which came from all parts of our far-flung line.

This is no formal History of the War in the strict or scientific sense of the phrase; no detailed record of naval and military operations. There have been many occasions on which silence or reticence seemed the only way to maintain the national composure. It is Mr. Punch's History of the Great War, a mirror of varying moods, month by month, but reflecting in the main how England remained steadfastly true to her best traditions; how all sorts and conditions of men and women comported themselves throughout the greatest ordeal that had ever befallen their race.