Native Tribes of South-East Australia/Chapter 10

CHAPTER X

INITIATION CEREMONIES, WESTERN TYPE

Location of the Two Types

For convenience I have taken a line, drawn from the mouth of the Murray River to the most southern part of the Gulf of Carpentaria, as defining the common boundary of the eastern and western types of initiation ceremonies. There are, however, between those of the Bora and those of the Dieri ceremonies which have a resemblance to both, but are more like those of the western type, and are therefore taken with them.

The Banapa and Bida Tribes

A line drawn about east and west, some three hundred miles from Adelaide to the north, will separate the tribes who are circumcised from those who are both circumcised and subincised. The former are called Banapa, that is, circumcised, and the latter Bida, being both circumcised and subincised. The Bida are to the north of the said line. There also a marked change takes place in the language. South of it the words Kadla, "fire"; Kaui, "water"; Kadna, "stone"; and Kukanaui, "watercourse," are pronounced as written, but from the above line northwards, the initial K before the vowel is dropped, and the words change to Adla, Aui, Adna, and Ukana.

The tribes on each side of this line are friendly, and when any mischief is in contemplation, they join in carrying it out.

The Banapa blacks are usually circumcised when about twelve years old. The operator seizes the prepuce with a kind of forceps, and then cuts off a part with a very sharp piece of flint. He puts the detached piece in his mouth, and then throws it to some of the other men. My informant did not know what was ultimately done with it. When approaching manhood, they are seized, and the urethra is slit down for about an inch. This is done by inserting a rounded piece of bone, and cutting down to it, with a sharp piece of flint, called Yudla. The Bidas look on themselves as being superior in race to the Banapas.[1]

The blacks here spoken of as Bidas evidently are part of that great section of the tribes which have the class names Matteri and Kararu, and which as the Parnkalla extend from Port Lincoln to beyond Port Augusta.

They are therefore connected with the Lake Eyre tribes, and I commence my description of the ceremonies of the western type with those of the Dieri tribe. These ceremonies are illustrated by legends, which are repeated at the ceremonies, and form the precedents for ceremonial procedure and practice. They purport to give an account of the origin of the ceremonies, and of the Mura-muras who established them. If you ask a Dieri, "Why do you do this?" he will reply, "Our Mura-muras did so," which is a final and conclusive answer.

The following legends have been obtained for me by the Rev. Otto Siebert, not only from the Dieri, but also from other tribes both to the north and south of them. The Kadri-pariwilpa-ulu.[2] A Legend of the Yaukorka, Yantruwunta, and Eastern Dieri

As soon as they had circumcised their father, they set out on their journey, everywhere circumcising youths and men. Coming to Kunauana[6] they found a number of people who had collected to circumcise some young men by means of fire. They approached quietly, and then, suddenly springing forward, they circumcised the youths with their Tula before the men knew what was being done. Seeking for those who had performed the operation so skilfully, and seeing the two Mura-muras enveloped in a mist, they shouted out, "Kadri-pariwilpa-ulu" These now came forward, and showing the Tula to them, said, "In future make your boys into men with this, instead of using fire, which has caused the death of many; thus they will all remain living, for 'Turu nari ya tula tepi.'"[7] Turning to the youths whom they had circumcised, they admonished them not to have access to women, or even to be seen by them, while their wounds were unhealed, nor to show their wounds to any one, otherwise they would certainly die.

The two Mura-muras wandered through all the land, carrying the Tula everywhere for circumcision, and were everywhere honoured as the benefactors of mankind.

The Malku-malku-ulu.[8] A Legend of the Karanguru And Ngameni

A large number of people had assembled at Tuntchara,[9] for the circumcision ceremony, at which there was an old Mura-mura who had provided Palyara[10] for food, and who rejoiced over the sweet smell thereof as it was being cooked. In the evening, as they sat round the fire, singing the Malkara[11] song, the old Mura-mura scattered the fire about, so that all those who were sitting round it were burned by the hot coals. After a painful night, the men at early dawn were painting themselves for the ceremony, and the six young men who were to be initiated were brought forward.[12] For each youth four men placed themselves so that their bodies were bent outwards. On these men the youth was laid, and in this manner two of them were circumcised by means of the fire-stick. Then the Malku-malku-ulu came up, and instantly rushing forwards circumcised the four other boys with their stone knife before the people knew what they were doing, thus saving the former from imminent death. Then going to the astonished men they presented their stone knife to the Woningaperi,[13] and told them to use it in future, and thus preserve their boys from death.

Having done this, the Malku-malku-ulu went onwards, and at Kutchi-wirina[14] they saw, at a little distance from them, a Kutchi in human form suddenly disappear into the ground. In alarm they altered their former course and went in another direction.

Decked with the Tippa-tippa, the young Mura-muras[15] wandered onwards, hunting and seeking food as they travelled, killing a Kapita in one place, and in another finding a tract covered with Manyura[16] on which they feasted. After resting here for some time, they travelled farther and found a kangaroo lair at Chukuro-wola.[17] Thinking that there might be a kangaroo in it, the one who had sharpest sight threw his spear into it, then also the spear of his comrade, who was one-eyed, but failed to find anything in the place. Immediately afterwards they found a lace-lizard, which they carried with them until it became stinking, and black on the under side. As they still wandered on they came to a large tract of country well covered with rushes, from which they made bags in which to carry their things. Then marching on they saw a kangaroo, at which the sharp-sighted one threw a spear, and then another, without hitting it. Then he threw all his companion's spears but one, which the latter had kept in his hand, who, then throwing it, killed the kangaroo, which they carried till they came to a place where they found water. Here they rested for a time; then lifting the kangaroo from the ground, and each holding it by one leg, they swung it round their heads, singing:—

| Mina | yundru | tayila | nganas | |||

| What | thou | eat | wilt? |

| Titiba-tiuba-tiuba | yundru | tayila | nganai | |||

| Tiuba[18] | thou | eat | wilt |

| Manakata-kaia | yundru | tayila | nganai | |||

| Manakata-kata | thou | eat | wilt |

Then they laid it on the ground; but no sooner had they done so than it jumped up and hopped away so swiftly that they could not overtake it. Before long, however, they killed another kangaroo. The one who had good sight sent the one-eyed one to fetch a Tula (stone-knife) so that he could flay off the skin. While he was seeking for a Tula the other began to remove the pelt. When the one-eyed man returned with the Tula the other replaced the skin over the carcase and pretended to try the Tula on it; then, saying that it was too blunt, he sent him to Antiritcha[19] to bring back a new one. During his absence he hastily skinned the kangaroo down to the hind legs, and when the other returned from Antiritcha and offered him the new Tula, he said, "Skin the kangaroo with it yourself." Beginning to do this, the one-eyed man found that the skin was quite loose, and said, "Why have you cheated me in this way by almost removing the skin?" "Do not be angry with me," said the other, "I only wished to have a joke with you, and surprise you with an almost skinned pelt."

Having completed the skinning, they fastened the edges of the skin to the ground, and raised up the middle, thus forming the sky. Having done this, they said with satisfaction, "Now from this time people can walk upright, and need not hide themselves for fear of the sky falling."[20]

Pleased with their work, they turned homewards, and coming to a good pool of water, one jumped in, saying, "Let us bathe ourselves here," but in striking the water it made a cut, which caused subincision. When he showed this to his companion, the latter at once jumped into the water, and he also became subincised. Looking at himself, he said, "Now I indeed am a complete man, but it hurts me."

Having conferred on mankind the use of the Tula, they now introduced the Dirpa,[21] so that by it a young man becomes a completed man.

The Malku-malku-ulu are the benefactors of mankind, and it is said that they still live, and are even sometimes seen. They wander about invisibly, to relieve the distress of others. They carry lost children to their camp, and care for them till they are found by their friends. Such is the legend as told at the ceremonies.

The southern Dieri say that the Malku-malku-ulu wander far to the north of their country, and that their camps can be recognised by the luxuriant growth of the Moku,[22] a plant the fruit of which no one may eat, because it is the especial food of the Malku-malku-ulu.

One of these camps is said to be at Narrani,[23] not far from Cattle Lagoon on the Birdsville road. This place is celebrated, among the tribes, because it was where the Malku-malku-ulu left their shields when they commenced their wanderings; for, being the benefactors of mankind, they did not need any weapons. But the original site of their home is said to be Antiritcha, where lives Atarurpa. Who this was I have been so far unable to ascertain.

The Yuri-ulu. A Legend of the Urabunna, Kuyani, and Southern Tribes

The Yuri-ulu travelled, coming from, the north, through all the land, bringing in the use of the Tula in circumcision. Thus they came to the Beltana country, at a time when a youth was about to be made into a man. When the men were going to burn him with fire, the Yuri-ulu went into the earth, the one on his right and the other on his left, waiting for the moment when they could help him. When a man approached with a red-hot fire-stick to perform the operation, the two Yuri-ulu rose out of the earth, and instantly cutting off the foreskin with their Tula, sank back into the ground invisibly. The men who were present were astonished at the fresh wound, and saw that the boy had been circumcised. They questioned each other as to who had done it, but no one could say. The feeling was such, that they began to say to each other, "Didst thou do this? or thou? or who?" and to grasp their weapons, when he who was about to have done the operation said that he would find out the cause. Seating himself on the ground, and striking it with a club, he sang continuously that he who had circumcised the boy should come forth. Then the Yuri-ulu rose out of the earth biting their long beards, and each holding a Tula in his hand before him.

Then, properly painted and adorned, they danced, and having given the Tula to the men, whom they admonished as if they had been youths, they disappeared, followed by the praises of the assembled men.

After showing themselves in many places as life-givers, they turned back, and at Katitandra,[24] one went west, and the other went east and northwards, bringing the Tula to every tribe.Thus they still wander, showing themselves at times as living, and as life-givers.

The following legend does not seem to have any direct connection with the last, but speaks of the Yuri-ulu as being boys who had not yet been circumcised, while in the other legend it speaks of them as being the originators of the practice. This is remarkable, because while the last legend belongs to the Urabunna, this one belongs to their neighbours, the Wonkanguru.

An old blind widower lived at Mararu[25] with his two sons the Yuri-ulu, who from their early youth had to provide him with food. As they grew older they went farther afield hunting, and delighted to kill young birds with the boomerang, and to cook them for their father when they returned in the evening to their camp. One evening on returning they observed that an old man had come to the camp, and had seated himself close to them. They informed their father, and he told them to call the stranger. They did so, but received no answer, and even when they went to him and invited him to come to their father, he still remained silent. Not troubling themselves more about him, they ate their food, and darkness having come on, they lay down and slept. In the early morning the boys went out hunting, and then the stranger, after having warmed his hands at the fire to strengthen himself, seized the blind man, wrestled with him, struggled with him, struck him on the face and breast, and scratched his face with his nails till the blood came. Then taking a piece of wood he scraped the blood off. By the struggling and the scratching the dimness of the old man's eyes had been removed, so that he could see better than before. As the stranger had done to him, so he now did to the stranger—struck him and scratched him, until the blood came, which he wiped off, and then recognised the stranger as his Kami. After they had recognised each other as Kami-mara,[26] they sat down together, and the stranger told him that he had come to consult with him as to the circumcision of his sons. The two having decided that the boys should be circum- cised, they commenced their preparations. Stone axes were sharpened, Kandri[27] melted, Ngulyi[28] collected, and the axes fastened afresh to their hafts with them. The boys were sent out early next morning to hunt, and to be out of the way while the old men were at work, so as not to see what they were doing. The old men went to a place where there was a Pirha,[29] that is, a great tree, which they cut down, separated a piece of the stem, and having taken off the bark, hollowed out the inside to make a great Pirha. Then they placed it in moist earth to soften, and kept its sides apart till it became cool.

The following morning they ornamented its sides with longitudinal markings, and, laying it on its back, the stranger struck it with his open hand. Listening, but hearing no reply, he struck it again harder, and there was an echo, which they thought was a reply by the women at a distance.

Early on the following morning, while the boys still slept, the stranger started homewards to Minka-kadi,[30] to call together the people for the ceremony at which the boys were to be circumcised. After a time he returned with them, bringing with him his two daughters, who, as he and his Kami-mara had agreed, should be the wives of the two boys.

Then while the two boys were out hunting, there was held a meeting of the old men, at which they consulted as to the manner of the ceremony. Towards evening, when the boys returned, a number of men were lying in wait for them, and two who were Kami and Kadi[31] to them, respectively, sprang forwards and laid their hand on their mouths, as a sign that they should not thenceforward speak to any but themselves during the ceremonies. Then they took them apart to a place, where they built a break-wind (Katu), and taught them the Kirha song. Early the next day the women and children and the two boys were sent to a distance to hunt, so that the men might hold a council undisturbed. They collected the Tula, and selected the good from the bad. Then they decided what presents the boys should give to the Woningaperi.

In the evening, when every one had assembled on the ceremonial ground, the Yuri-ulu returned, and, as they approached, a few of the men joined them, then more, until by the time they had reached the ground they were surrounded by a great crowd, not counting the women and children. The Yuri-ulu were then taken behind their Katu (break-wind) to be decorated with emu and cockatoo feathers. This having been done, the boys were openly led to the ground, across which they marched. Each one, standing on a Kirha which rested on two spears, and supported by his Kami, grasped the Kalti[32] as high up as possible. Thus they remained for some time. Their Ngandri (mothers) were sitting in a row which extended from their Katu to the Kalti, having on each side the Katu of one half of the Ngaperi (fathers). The seated mothers, one after the other, rose and went to each of the boys, and with her open hands stroked him about the neighbourhood of the navel. When the last one had returned to her place, each boy was carried to his Katu on the back of one of his Kami, where his ornaments[33] were taken from him, and carried to his father to be given to those who were to perform the rite of circumcision on him. Then was heard the muffled sound of the Kirha being struck, and, shortly after, the sisters of the Yuri-ulu came forward, and commenced their dance in parties of four each, one of the elder girls and one of the younger. At the end of this the men carried each other about on their backs.

About midnight the women were driven away from the ground to their main camp, the Ngandri only remaining behind, at a little distance, forming a connection between the men at the ground and the women at the camp, but also keeping the latter quiet and seeing that none of them watched the ceremonies, the great Pirha was struck several times, and replied to by the Ngandri striking their stomachs with the open hand.

The boys were now taken to the camp of the Ngaperi, and there carefully watched by their Kami and Kadi, so that they should not sleep, being shaken up into wakefulness when they dozed off. Then the Woningaperi and the Taru (father-in-law) came up to them, decked with feathers, and three Neyi of each boy placed themselves together so that the boy could be laid on their backs, and there circumcised by their Taru. This being done, their Woningaperi, Kadi, Kami, and especially the Taru, were placed before

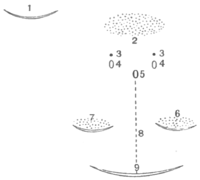

DIAGRAM XXXI. them and the last named gave to each a bundle of the hair of one of his daughters as a sign that she should be his promised wife. The boys were then taken back to their Katu.

1 is the Katu of the Yuri-ulu; 2, spectators, women and children; 3, the Kalti; 4, the two Pirha, each lying on two spears in front of a Kalti; 5, the great Pirha; 6 and 7, the Katus of the Ngaperi; 8, the Ngandri sitting in a row; 9, the Katu of the Ngaperi.[34]

The Dieri Ceremonies

It is the Pinna-pinnaru, that is, the principal Headman of the Dieri tribe, who decides when the youths shall be passed through the several stages of the initiation ceremonies. When he finds that there are a sufficient number ready, he decides on the time. The matter is brought by him before the council of elders, but so far as relates to the time and place he decides, and also which youths are to be initiated.[35]

Knocking out the Teeth

The knocking out of the two lower middle front teeth is practised sometimes earlier than in tribes which have ceremonies of the eastern type, and is not confined to boys only. When a child is from eight to twelve years of age, the teeth are taken out in the following manner. Two pieces of the Kuya-mara tree, each about a foot in length, and chisel-shaped, are placed one on either side of the tooth to be extracted, and driven tightly. Some wallaby skin is then folded two or three times and placed on the tooth, and a piece of wood about two feet long being placed against the wallaby skin, is struck with a heavy stone. Two blows suffice to loosen the tooth, which is then pulled out by the hand. This is repeated with the second tooth. As soon as the tooth is extracted, a piece of damp clay is placed on the gums to stop the bleeding. The boy, or girl, as the case may be, is forbidden during the ceremony, and for three days after, to look at the men who were present, but who turned their faces away. It is thought that a breach of this rule would cause the child's mouth to close up, and that consequently it would not be able to eat afterwards. The teeth are placed inside a bunch of emu feathers smeared with fat, and are kept for about twelve months, under the belief that if they were thrown away the eagle-hawk would cause larger ones to grow up in their places, which would turn up over the upper lip and thus cause death. The boy's teeth are carefully kept by the boy's father, and long after the mouth is completely healed he disposes of them, in the company of some old men, in the following manner. He makes a low rumbling noise, not using any words, blows two or three times with his mouth, and then jerks the teeth through his hand to a distance. He then buries them about eighteen inches in the ground. The jerking motion is to show that he has already taken all the life out of them; as, should he fail to do so, the boy would be liable to have an ulcerated mouth, an impediment in his speech, a wry mouth, and ultimately a distorted face.[36]

This is another instance of the belief that there is an intimate connection between the teeth and the person from whom they were extracted, even at a distance, and after a considerable time. I have before referred to this belief.

The Karaweli-wonkana

The Karaweli-wonkana,[37] or ceremony of circumcision, is performed when a boy is about nine or ten years of age. The proceedings are commenced by a woman walking up to the boy in the early part of the evening and quietly slipping a string over his head, to which is attached a mussel shell (Kuri). This is done by a married woman, who is not of his class or totem, or in any way related to him. This action usually brings about a disturbance, for neither the boy nor his father have been made aware of what was intended. Directly the boy finds the shell suspended round his neck he jumps up, and runs out of the camp. His father becomes enraged, for it is generally the case that fathers think their sons are too young to undergo the painful operation. He therefore attacks the elders, and a general fight ensues.

From the moment the boy runs out of the camp until several months after the operation, no woman, excepting immediately after the ceremony, is supposed to have a sight of him. On the night preceding the circumcision the women see him, or he is shown to them, for a few minutes. At this time all the available tribes-people are collected, and for the time there is unrestricted intercourse between those who are in the relation of Pirrauru to each other. Nothing is said of this at the time, but it may cause sanguinary quarrels afterwards. It is not spoken of at the ceremony, because those who may be jealous dare not show their feeling at the Karaweli-wonkana, lest it should be said that they are attempting to undermine and tamper with the old-established customs.

Immediately before a boy is circumcised, a young man picks up a handful of sand and sprinkles it as he runs round the outside of the camp. This is to keep out Kutchi and to keep in the Mura-mura of the ceremonies.[38]

It is the Kami and the Kadi who lead away the boy after he is circumcised. The Neyi and the Kaka provide him with food, and later on accompany him. Above all, however, they must be elder people, so that their teaching shall be respected. For this reason, elder rather than younger members of the relationship group are preferred.[39]

As soon as the rite has been performed the boy's father stoops over him, and gives him a new name.[40] This name has been invented by him long before, when the boy was much younger. It might be that when he was lying ill and in pain, he said something to his wife, using the child-name of his son. She repeating what he has said, he adds to it something more, now using the Matteri-tali, or man's name, of his son, which his wife now hears for the first time. If he feared that he was going to die, he would hand over the name to his brother, the Ngaperi-waka, or little father, own or tribal, of his son. This is in order that he may be able to announce the boy's new name when he is circumcised. Such a name, so given to a man in charge, would be kept as a sacred trust.

Such a name is taken from the legend of the boy's Mura-mura. This is not inherited from his mother, as is his Murdu, but from his father.

The boy's name is not exactly a secret name, but a youth when he has been once honoured with his Matteri-tali, and has been announced by it as a man, is too proud to let himself be called a boy.

There are eight tribes which have separate Karaweli-wonkana ceremonies, and each has its particular Karaweli-malkara, that is, the song belonging to the ceremonies.[41] Of these, that of the Pirha and the Wapiya are mentioned in the legend of the Mankara-pirna-ya-waka (Appendix).

This inheritance of the legend of the individual's Mura-mura shows that the Mura-mura is in some manner the ancestor, and connects the Dieri beliefs with the legends of the Arunta, and the Alcheringa ancestors. So far, however, I have not any evidence that the Dieri hold the Arunta belief in the re-incarnation of the supernatural ancestor.

The Wilyaru

The next ceremony after that of the Karaweli-wonkana is called Wilyaru. A young man without previous warning is led out of the camp by some old men who are of the relation of Neyi to him, and not of near, but distant relationship. On the following morning the men, old and young, except his father and elder brothers, surround him, and direct him to close his eyes. One of the old men then binds the arm of another old man tightly with string, and with a sharp piece of flint lances the vein about an inch from the elbow, causing a stream of blood to fall over the young man, until he is covered with it, and the old man is becoming exhausted. Another man takes his place, and so on until the young man becomes quite stiff from the quantity of blood adhering to him. The reason given for this practice is that it infuses courage into the young man, and also shows him that the sight of blood is nothing, so that should he receive a wound in warfare, he may account

it as a matter of no moment.[42] The next stage in the ceremony is that the young man lies down on his face, when one or two of the other young men cut from three to twelve gashes on the nape of his neck, with a sharp piece of flint. These, when healed into

FIG 39.—URABUNNA MAN, SHOWING WILYARU CUTS ON THE BACK. raised scars, denote that the person wearing, them has passed through the Wilyaru ceremony. A Dieri points with pride to these scars as showing that he is Wilyaru. Until the scars are healed, he must not turn his face to a female, nor eat in the sight of one.

Immediately after the Wilyaru, a bull-roarer, called by the Dieri Yuntha, is given to the youth. It is from six to nine inches long, by two to two and a half wide, and one-eighth thick, and a string is attached to it, made of human hair, or of native flax, from ten to twelve feet in length.[43]

It was some time after the Wilyarn ceremonies were made known to Mr. Gason that a Yuntha was shown to him, and he was required to promise never to show it to women, or to let them know that he had seen it. When he was initiated in an actual knowledge of the ceremonies, and had been present at them, he was required to promise that he would keep all their secrets, and never, even by a tracing on the ground, show them to women.

A Yuntha which has been made use of at a Wilyaru is marked with a number of small notches on the side and at one end.

If by chance a Yuntha is lost, the finder examines it to see whether it bears any notches; and, if it does, he carefully secretes it, and acquaints the elders of his find. If there are no notches, he treats it merely as a plain piece of wood, and he may even carry it to the camp and make a joke of it. The Yuntha is one of the most important secrets of the tribe, and the knowledge of it is kept inviolate from the women. The belief is that if a woman were to see a Yuntha which had been used at the ceremonies, and knew the secret of it, the Dieri tribe would ever afterwards be without snakes, lizards, and such other food.

When a Yuntha is given to the youth after the Wilyaru ceremony, he is instructed that he must twirl it round his head when he is out hunting. The Dieri think that when the Yuntha is handed to the young Wilyaru, he becomes inspired by the Mura-mura of this ceremony, and that he has the power to cause a good harvest of snakes and other reptiles by whirling it round his head when out in search of game. About a week after the ceremony, and on some dark night, he approaches the camp and commences to whirl the Yuntha, so as to make a loud noise. When this is heard, the men, excepting the elders, go out to see him, carrying with them food, which the women have prepared. They cheer up and encourage the young Wilyaru who, when he departs again, is accompanied by some of the young men, who keep him company till his wounds are healed. The young man is never seen by the women, from the time he is made Wilyaru till the time when he returns to the camp, after perhaps many months. Before he shows himself at the camp, all the blood which was caused to stream over him must be worn off, and the gashes must be thoroughly healed. During the time of his absence his near female relatives, Ngandri, Kaku, Ngatata, and Buyulu, become very anxious about him, often asking as to his whereabouts. There is great rejoicing in the camp when the Wilyaru returns finally to it, and his mothers and sisters make much of him. He is prohibited from speaking to any of the actual operators at the Wilyaru ceremony until he has given some kind of present to each. As he hands his present to one of the operators, he is told that he may speak. This custom is carried out strictly, and Mr. Gason said that he never witnessed the ceremony without afterwards receiving a present from the youth, and he was never able to induce one to speak till a present had been given by him.

The Mindari[44]

After the Wilyaru the next ceremony is that of the Mindari, which is held about once in two years, either by the Dieri or some one of the neighbouring tribes. When there is a sufficient number of young men in the tribe who have not passed this ceremony, and when the tribes are friendly with each other, a council is held, for instance by the Dieri, to fix on the time and place. This being settled, women are sent to neighbouring tribes, to invite them to be present, the preparations for which—building the huts and collecting food—is carried on, and generally occupies six to eight weeks. As soon as the first members of an arriving party come in sight, the Mindari song is sung, to show the strangers that they are received as friends. At length, when all have arrived, they wait for the full of the moon, so as to have plenty of light during the ceremonies, which commence at sunset. Meanwhile at every sunrise, and at intervals, all the men at the camp join in the Mindari song.

On the evening of the ceremony the young men are carefully dressed. The hair of the head is tied with cord so as to stand straight up, and tails of rats (Thilpa) are fastened to the top. Feathers of the owl and the emu are affixed to the forehead and the ears, and a large girdle (Yinka), made of human hair, is wound round the waist. The face is painted red and black.

The ceremonies commence by the men, women, and children shouting at the full force of their lungs for about ten minutes. Then the women go a little way from the camp, to dance by themselves, while the men proceed to a distance of about three hundred yards, to a piece of hard ground which has been neatly swept, and on which a ring has been marked. The ceremonies are opened by a little boy about four years of age, who is decked out with the down of the swan and the wild duck attached to his head, and with his face painted red and black. He dances into the ring, followed by the old men, and this dance continues for about ten minutes, when the boy ends it by running out of the ring.

All the young men then go through a number of evolutions, and this is continued till the sun rises, when the ceremony terminates and all retire to sleep during the day.

The reason for holding this ceremony is to enable all the tribes to meet and to amicably settle any disputes that may have occurred since the last Mindari.

The Kulpi[45]

Connected with initiation, there is the Kulpi rite, now known to anthropologists as subincision. At the secret council at which the circumcision ceremony is determined upon, the Headman and the heads of totems fix upon the youths who are to become Kulpi. Certain men are fixed upon to see this carried out, and they are responsible to the Headmen for the proper incision being made—clean, straight, and without any unnecessary violence.

No warning or notice is given to the young man. He goes out hunting with others as usual, when, on a signal being given by one of the party, he is suddenly pinioned from behind, and thrown down. He naturally struggles desperately, thinking that they are going to kill him, and calls out to his father and mother in most piteous terms, until his mouth is covered by some one's hand. Other men, who have been lying concealed, now rush up and tell him not to be frightened, for they are only going to make a Kulpi of him. If, however, he still continues to struggle, he is quietened by a blow on the head, but as a rule he submits quietly, finding himself in their power, and that moreover his life is not in danger. The old men and the bystanders encourage him by saying that he must not mind the pain, for it is nothing to what he has suffered during circumcision. The operation may last for twenty minutes, and many youths faint after it is over. In one such instance, which Mr. Gason gave me, the young man struggled violently, large drops of sweat broke out on his forehead, and tears flowed from his eyes; yet he did not make a sound or murmur, till the operation was over, when he uttered a deep groan, several sighs, and then gradually fell back into the arms of the men who were, holding him. The wound was staunched with sand. Mr. Gason lost sight of him for several months, and when he saw him again he looked quite healthy, active, and smart, and the wound had completely healed. He presented Mr. Gason with a carved boomerang, making signs to him to accept it. He, knowing the custom in such cases, did so, and it was only then that the youth ceased to be Apu-apu, that is dumb, and spoke to him. A Kulpi, as is the case with the Karaweli and the Wilyaru, may not speak till he has given presents to those who were at the ceremony, either as operators or as witnesses.

It is thought that the presence at the operation of some distinguished man, such as a great fighting-man, or the head of a totem, tends to give strength to the young man while he is undergoing it.

It is only when a young man has been made Kulpi that he is considered to be a thorough man, and in this sense Kulpi is the highest stage in the initiation ceremonies.

Professor Baldwin Spencer tells me that in all the tribes with which he is acquainted who practise subincision, all the men are subject to it. According to the information given me by Mr. S. Gason, twenty years ago, only a certain number of the men of the Died tribe were Kulpi.

From further inquiries which I have made I am now satisfied that the practice of Kulpi in the Dieri tribe was, and is, universal, and that Mr. Gason must have been in error in the above statement.[46]

The Wilpadrina[47]

On the young women coming to maturity, there is a ceremony called Wilpadrina, in which the elder men claim, and exercise, a right to the young women. The other women are cognisant of it, and are present.

The Rites in the Coast Tribes

In the Yerkla-mining tribe the rite of circumcision is very strictly observed. For some time before a youth is circumcised no woman, married or single, is allowed to take food from him, nor are they permitted to see him take food from any one else, if they can avoid doing so.

When it is decided that a certain boy shall be circumcised, the medicine-men, having held a council, call upon some of the old men to assist in capturing him. He, being aware of their intention, has previously taken to the bush, living a watchful and lonely life. The natives call him Kokitta-mining, that is, wild man. If they can get on his track, he is easily surrounded, but he sometimes evades them for months. The time for circumcision is when the youth is about eighteen years of age, that is, after he has got whiskers.A place is chosen for the ceremony which is not likely to be visited by any one, and three days are devoted to hunting and providing food.

The operation is performed by men of one of the neighbouring tribes, and the boy is taken away to a part of the tribal country fixed on by his male relations. There is little or no ceremonial observance, but some of the old men take the boy by the wrists, and pull him violently from one side to the other, uttering at the same time a kind of chant consisting of a series of "Eyah!" Whether through excitement, or anticipation of the ceremony, or by being swung about from one side to the other by the old men, the boy becomes somewhat dazed. Then the operator approaches, and suddenly seizes the prepuce, and cuts it off with a piece of flint. The wound is seared with a fire-stick. String is made from opossum and wombat hair, with which the youth is decorated, particularly about the head; and a sort of apron is made with which he is covered till the wound is healed.

After a week or a fortnight, if he is sufficiently recovered, he rejoins the tribe, and there is a great feast and corrobboree, at which both sexes join in the dancing.

The boy never sees who circumcises him; neither does he know the name of the man till the operation is over. Then he is taken away by his nearest male relation, who provides food for and looks after him.

No women are permitted to be on the ground where the circumcision is done, and must camp some distance away from the place, nor is it allowed for them to hear the matter spoken of. If any reference is made to the ceremony in their presence, they at once stop their ears with their hands.

If the boy is of the Wenung division, he is circumcised in the morning. Boys of the other classes are not, and they are left tied on the ground till the Milky Way is seen in the sky. Then the lad is asked, "Can you see the two black spots?" When he has seen them, he is allowed to go to his camp; and then the medicine-men tell him the following legend. A very long time ago a great bird came and devoured all the people, excepting three men and one woman. These were one Budera, one Kura, one Wenung, and a Kura woman. The men fought the bird and killed it; but, after it was dead, only two spears were found in the body, one belonging to the Kura, and one belonging to the Wenung man. Then they went up to the Milky Way; and the name given to two black spots, to which they went, is Nug-jil-bidai-tukaba, or the "far-away men." After the Budera man, who remained behind, had grown old, and had many children and grandchildren, he also went up to the stars; but he is only seen when he walks across the moon, and then he is angry. Budera's children were boys, and they went inland a great distance, and were absent a long time. On their return each boy brought back with him a captured wife. The Budera, before he died, marked them with their class marks.

When the rite of subincision is to be carried out, it causes great excitement in the tribe. It takes place some time after circumcision, and is called Wandai-ngrungur. When a young man has passed through this ceremony, he may claim his promised wife.

In making the subincision, the youth is laid on the ground flat on his back, his wrists and ankles being fastened to the earth by means of kangaroo sinews and pegs. A second or assistant medicine-man sits across his chest, with his face towards his feet, performing two functions at once, namely holding him down, and assisting the principal operator. The instrument used is called Meru, and is a wooden haft with a piece of very sharp flint bound on one end with sinew and mallee-scrub gum.

The wound is treated by bandaging it with a piece of flat smooth wood and the inner bark of an acacia. One of the medicine-men spins a tassel of wombat or opossum fur, which is suspended from the waist of the patient by the operator, so as to hang down and keep the flies and dust from the wound. Until it is healed, the youth has allotted to him three Wiiah, or mothers, to look after him and provide for him, until he is able to do so for himself, and through their lives they look after his welfare.It is thought that if any one but a medicine-man touches a Meru, it will cause great sickness to the young man on whom the flint was used. In such a case, if the young man became ill, the offender would have to go away and live by himself for a time. But if the young man died, the offender would be killed.

There is in this tribe a rite similar to the Wilpadrina of the Dieri, accompanied by an operation by a medicine-man. Three men of the relation of father to the girl are allotted to her, who provide her with food till her wound is healed.[48]

The tribe at Fowler's Bay adjoins the Mining, and at certain times of the year the two tribes have a ceremonial meeting. Boys are circumcised at the age of about fourteen, and subsequently subincised. The medicine-man who operates swallows the prepuce, with some water. He never speaks to the boy or his parents, does not go to their camp fire, excepting in very cold weather, nor accept any food from them unless it were sent by some other person.[49]

These tribes east of the Mining adjoin the Parnkalla, who lived at Port Lincoln, whose northern extent includes the Beltana country, which is mentioned in the legend of the Yuri-ulu already given. The Parnkalla therefore bring us into the region of the Lake Eyre ceremonies. I find an account of the initiation ceremonies of this tribe in a work by C. W. Schürmann,[50] from which I shall quote, for comparison with the accounts already given.

The names of the ceremonies which form the several parts of initiation in this tribe supersede the ordinary names of the youths during the time which intervenes between the ceremonies, or immediately follows them.

The three ceremonies are the Warrara, when a boy is about the age of fifteen; the Pardnappa, at the age of sixteen or seventeen; and the Wilyalkinyi, when about eighteen.

The Warrara Ceremony

Mr. Schürmann gives a description of these ceremonies at length, which is briefly as follows. The Warrara is conducted from the camp blindfolded by a man called Yumbo, who attends the novice during the whole of the ceremony. This is held at some remote place whereat women and children are not permitted to be.

The novice is laid on the ground, covered with skins, the Yumbo sitting by him. The rest of the men prepare a number of bull-roarers, called Pullakalli, which, when tied to a handle, produce a piercing sound.

One of the men then opens a vein, causing the blood to run on the Warrara's head, face, and shoulders, also in a few drops into his mouth. A number of precepts are now impressed on him for his future conduct. These are, not to associate any longer with his mother, or the other women, nor with children, but to keep company with men. Not to quarrel with, or ill-treat, women. To abstain from eating forbidden food, such as lizards. He is warned not to betray what he has seen and heard, under pain of being speared, thrown into the fire, or otherwise dealt with.

On the following morning the novice is taken to the women, who have camped separately. A smoky fire has been made with damp grass, and the Warrara is conducted backwards to it, where one of the women is placed to receive him. He is caused to sit on the grass, and she dries and rubs his back, which has been previously covered with blood, with her skin rug. Then one of the little boys chases him through a lane formed by the body of men.

For three or four months the Warrara must keep his face blackened with charcoal, speak in low whispers, and avoid women.

The children are never allowed to approach a place where a Warrara has been made.

The Pardnappa Ceremony

The Pardnappa ceremony commences with the novice's attendant shouting "Pu! Pu!" All the women of the class to which the Pardnappa belongs, whether Matteri or Kararu, touch the shoulders and necks of the men of the same class, to express their approval of the intention to make the boy a Pardnappa.

The ceremony takes place at some neighbouring water, where game has been roasted and is now eaten. After this, the Pardnappa goes apart with those lads who last underwent the same ceremony.

One of the men takes his place in the fork of a tree of moderate height, and others crowd round and place their hands and heads against the stem of the tree, so that their backs form a sort of platform, on which the Pardnappa is placed backwards. His arms and legs are stretched out and held fast, and the man sitting in the fork of the tree descends and sits on his chest, so that he is unable to move any limb of his body.

The circumciser, who is usually a man from some distant place, performs the operation with a piece of quartz, while the lookers on recite a charm, which is supposed to have the power of allaying pain.

The Pardnappa, whose hair, prior to the operation, has been allowed to grow to a great length, has it now secured on the crown of his head in a net made of opossum-fur string. He wears a tassel of the same over the pubes, which is worn for many months afterwards.

At this period, although without any particular ceremony, subincision is performed. In support of this practice, they say it was observed by their fathers, and must therefore be upheld by themselves.

The Wilyalkinyi Ceremony

The ceremony of Wilyalkinyi is the third through which a young man has to pass, and at it "a sort of sponsors are appointed" called Indanyanya.

The Wilyalkinyi are taken blindfolded from their camp to a short distance, where the Indanyanya keep them for a time, shutting their eyes with their hands. The lads are then taken farther, and laid flat on the ground, and covered with skin rugs. At this time chips of quartz are prepared, and new names are invented for the Wilyalkinyi. thing being ready, several men open veins in their lower arms, while the young men are raised to swallow the first drops of the blood. They are then told to kneel on their hands and knees, so as to give a horizontal position to their backs, which are covered with blood. As soon as this is sufficiently coagulated, one of the men marks, with his thumb, the places where the incisions are to be made, namely, one in the middle of the neck, and two rows from the shoulders down to the hips at intervals of about a third of an inch at each cut. These are named Manka, and are ever after held in such veneration that it would be deemed to be great profanation to allude to them in the presence of women. During the cutting, which is done rapidly, as many of the men as can find room crowd round the youths, repeating in a subdued tone, but very rapidly, the following formula: "Kauwaka kanya marra marra, karndokanya marra marra pilbirri kanya marra marra." This incantation, which is derived from their ancestors, is apparently devoid of any meaning to them, but the object in saying it is to alleviate the pain of the young man, and to obviate any dangerous consequences from the lacerations. After the incisions are completed, all the youths are allowed to stand up and open their eyes. The first thing they behold is two men coming towards them, stamping, biting their beards, and swinging the Witarna[51] with such fury as if he intended to dash it against their heads; but when approaching, they place the string of the instrument round the necks of the youths in succession. Several fires are made to windward, so that the smoke will be blown over the young men. The Wilyalkinyi are given a new girdle for the waist, spun of human hair, a bandage tightly tied round the upper arm, a string of opossum hair round the neck, the end of which falls down the back, where it is tied to the girdle, a bunch of green leaves over the pubes, and, lastly, their faces, arms, and breasts are painted black. Then the men crowd round them and give advice for their future conduct. This is to abstain from quarrelling and fighting, to avoid women, and to refrain from talking loudly. The last two injunctions are observed scrupulously till the men release them four or five months later. Till then they live and sleep separately from the camp, and speak in whispers. The releasing of the Wilyalkinyis consists merely in tearing the string from their necks, and covering them with blood, in the same manner as at the earlier ceremony. After that they are admissible to all the privileges of grown men. The women and children, as has been already said, are not permitted to see any of the above ceremonies, and are camped on these occasions out of sight of the men. If their business requires them, in fetching water, wood, or anything else, to be in sight of where the men are, they must cover their heads with a skin rug and walk in a stooping posture. Any impertinent curiosity on their part is punishable with death, and it is said that instances have occurred in which this punishment has been inflicted.

I have quoted this account of the ceremonies of the Parnkalla for the reason that it gives a fairly full account of them, and also because it completes the view of these of the Lake Eyre tribes, to which the Parnkalla belong by their organisation and customs. The Wilyalkinyi ceremony is evidently the equivalent of the Wilyaru of the Dieri.

The Narrang-ga Ceremonies

On the opposite side of Spencer Gulf to Port Lincoln there is the Narrang-ga tribe. It also practised circumcision, but not subincision, and therefore it belongs probably to the Banapa already mentioned.

When the boys became aware that they were likely to be wanted for that rite, they sometimes concealed themselves in the bush, but were hunted down. At the ceremony the boy is caused to drink blood from his own arm. In the actual rite one of the old men places his hands over the boy's eyes, and after the prepuce is cut off, it is buried at the place of initiation. For about twelve months the young man is obliged to carry with him a fire-stick, wherever he goes, and it is only after his return to the camp that he is allowed to marry. At the ceremonies no one speaks above a whisper. The bull-roarer is used, but it is not lawful for any woman, or uninitiated person, to see it. Formerly such an offence

FIG. 40.—THE NAKRANG-GA BULL-ROARER. 1 AND 2 ARE OPPOSITE SIDES. ×½ was punished with death, both of the person who showed it and the person to whom it was shown.[52]

Ceremonies at Encounter Bay

The initiation ceremonies at Encounter Bay are briefly described by H. E. A. Meyer.[53] They appear to be nearly the same as those of the Narrinyeri, whose country, according to the Rev. George Taplin, includes that of the Encounter Bay tribe.

Mr. Meyer says that in the summer time, when the nights are warm, several tribes meet together for the purpose of fighting, and afterwards dancing and singing. At such a meeting it is understood that some of the boys are made into men. In the midst of the amusements the men suddenly give a shout, and all turn towards two boys, who have been chosen, and who are suddenly seized and carried away by the men. The females cease their singing. From this time they are not allowed to accept any food from these young men. As soon as these latter are brought to the place appointed for the ceremony, two fires are lighted, and the young men are placed between them. Several of the men now pluck all the hair from the body, except the hair of the head and the beard. As soon as this is done, the whole body, except the face, is rubbed with grease and red ochre. The young men are not allowed to sleep during the whole night, but must either sit or stand until the morning, when the men return to them. They then go into the bush until sundown, when they return to their male relations, and obtain some food, but must avoid the females. They are now considered to be "Rambe" or sacred, and no female must accept any food from them, not even their own mothers, until such time as they are allowed to ask for a wife. For about a year the two young men who have been made men at the same time assist each other in singeing and plucking out each other's beards, and apply the grease to the face as well as to the other parts of the body. When the beard has grown again to a considerable length, it is a second time plucked out, after which they may ask for wives.

Narrinyeri Ceremonies

The Rev. George Taplin says[54] that, among the Narrinyeri, the boys are not allowed to cut or comb their hair, from the time when they are about ten years of age till they undergo the rites by which they are admitted to the rank of men. When the beard of a youth has grown to a sufficient length, he is made Narumbe or Kaingani, a young man. In order that this ceremony may be properly performed, and the youth admitted as an equal with the men of the Narrinyeri, it is necessary that men of several different clans should be present on the occasion. A single clan cannot make its own youths Narumbe, without the assistance of others.

Generally two youths are made Narumbe at the same time, so that they may afterwards, during the time that they are Narumbe, assist each other. They are seized at night, suddenly, by the men, and carried off to a spot some little distance from the Wurley,[55] the women resisting, or pretending to resist, the seizure, by pulling at the captives, and throwing firebrands at their captors. They are soon driven off to their Wurleys, and are compelled to stop there, while the men proceed to strip the two youths. Their matted hair is combed, or rather torn out with the point of a spear, and their moustaches and a great part of their beards are plucked out by the roots. They are then besmeared with oil and red ochre from head to foot. For three days and nights the newly made Kainganis must neither eat nor sleep, a strict watch being kept over them to prevent either. They are allowed to drink water, by sucking it up through a reed. The luxury of a drinking vessel is denied to them for several months after initiation. When, after three days, they are allowed to sleep, they rest their heads on two crossed sticks. For six months they walk about naked, or with merely the slightest covering round their loins. The condition of Narumbe lasts until their beards have been pulled out three times, and each time has grown again to about the length of about two inches. During all that period they are forbidden to eat any food which belongs to women, and the prohibition extends to twenty different kinds of game. If they eat of any of these forbidden things, it is thought that they will grow ugly. Only those animals which are the most difficult to obtain are allowed for their subsistence. Everything which they possess, or obtain, becomes Narumbe, or sacred from the touch of women. Even the bird hit by the club, or the kangaroo speared by their spear, or the fish taken by their hook, is Narumbe. Even if their implements are used by other men, the proceeds are forbidden to all females.

They are not allowed to take wives until the time during which they are Narumbe. But they are allowed the privilege of promiscuous intercourse with the younger portion of the sex.

Any violation of these customs is punished by the old men by death, sometimes by Millin, that is, magic, but often by more violent methods.

The tribes which lived on the Lower Murray and Darling Rivers and extending back to the Barrier and Grey Ranges did not practise circumcision or subincision, but had initiation ceremonies which, in some respects, resembled those of the western type.

Dr. M'Kinlay, who lived among the Maraura-speaking tribes of the Lower Darling River in the early days of settlement, told me that before the young men were admitted to rank as men they were subject for some years to very strict discipline. Every six or seven years there was a great meeting from long distances for the purpose of passing eligible candidates. In one case which came under his notice, a young man was seized by two or three men, stretched out on the ground, and all the hair plucked from his cheeks and chin, and given to his mother, who was present, crying and lamenting. He was then taken away for a week into the scrub, where he underwent some discipline; and when he returned he looked miserable and half-starved. There was no circumcision in the Maraura tribes.

The Itchumundi Ceremonies

In the tribes of the Itchumundi nation, circumcision is practised by the Wilga, Kongait, and Bulalli tribes. The Tongaranka knock out only one incisor and depilate the private parts. The tooth is either the right or the left upper incisor, according as the boy uses his right or left hand in using a digging-stick. He carries the tooth and hair with him for about three weeks; and then, selecting a tree which stands with its roots in a water-hole, he cuts a hole in the bark and conceals them therein.

I am informed that, during the ceremonies, he drinks the blood from the arm of one of the old men, and is supposed thereby to be infused with a manly spirit, and to lay aside boyish things.

After the ceremonies, he is prohibited from eating animal food, until the sore caused by knocking out the tooth is healed.

Two bull-roarers are used in these ceremonies. The larger of the two is called Bungumbelli, and is the charge of the medicine-man of the tribe. A notch is made on it for each ceremony at which it is used. The smaller one is called Purtali and is used not only at the ceremonies, but also in cases of sickness by the medicine-men as a sort of exorcism. The youth after the initiation receives presents from the men to give him a start in life, such as rugs, weapons, and such like. He is then permitted to be present at the consultations of the men.[56]

The principles which underlie the ceremonies of the western type are in some points the same as those of the eastern type. The youths are separated from the control of their mothers and from the companionship of their sisters, are usually taboo as to women during their novitiate, and are generally initiated by the men of the other moiety of the tribe.

The inculcation of obedience to the elders and observation of the tribal morality is common to both, but they are sharply distinguished by the rites of circumcision and subincision, and the practice of bleeding at the Wilyaru and similar ceremonies.

There is no direct evidence to show from whence these ceremonies have been derived, but the legends suggest a line of inter-tribal communication from the north to the south, and I incline to the belief that a northern origin will ultimately be assigned to these ceremonies. Whether they overlie older ceremonies of the eastern type or the reverse, I am unable to say. Perhaps when the initiation ceremonies of Western and Northern Australia have been carefully studied and described, it may be possible to form some opinion as to this question.

There is an absence in the western tribes of a belief in an anthropomorphic Being by whom the ceremonies were first instituted.[57]

- ↑ Dr. M'Kinlay.

- ↑ Kadri in Yaurorka, or Kaiari in Dieri, is "river-course," or "creek"; Wilpa is the sky; Uli is the dual form, "both." Kadri-pariwilpa-ulu is also the name of the Milky Way.

- ↑ Peri-gundi is a crooked, twisted place. Peri is a spot or place; gundi, or more properly Kunti, is "crooked" or "twisted." Lake Buchanan.

- ↑ Tula is the word for a flint knife used for circumcision, but is used also for any sharp flint used for cutting.

- ↑ Mira is "inflammation." This shows that while the Dieri attribute most deaths to evil magic, by "some one giving the bone," they also admit other causes. They say that long ago a great sickness came from the north and killed so many that when they woke in the morning one was alive and the other dead.

- ↑ Properly, Kudna-ngauana, from Kudna, "filth," "excrement," and ngaua, "light."

- ↑ That is, "Fire is death, and the stone is life."

- ↑ This is a Ngameni word, the Dieri equivalent being Tippa-tippa-ulu, meaning "the two with the Tippa" that is, a pubic tassel, made from the tails of the Kapita, the native rabbit (Peragale lagotis), and worn by the men for decency.

- ↑ This Ngameni and Karanguru word means "powdered human bones," and refers to a number of bones which are said to have accumulated there, by reason of deaths through the use of fire in circumcision.

- ↑ This is the long-snouted marsupial rat.

- ↑ Malkara is the word for the songs sung at these ceremonies.

- ↑ This description of the procedure at the ceremony of circumcision is part of the legend. For every custom and rite there is an equivalent in a Mura-mura legend. If, for instance, one asks a Dieri, "Why do you have this custom?" the reply is, "Our Mura-muras had that custom too, so we must follow them."

- ↑ Woningaperi is the equivalent of the Arunta Atwia-atwia, mentioned by Spencer and Gillen, p. 647. He is the man who performs the rite of circumcision.

- ↑ Kutchi is a spirit of the dead, a ghost; wirina is "to go in."

- ↑ Only the circumcised men can wear the Tippa. It is not only worn for decency, but is also by the men of the Pinya fastened to their beards. These, to show their anger, put the end of the Tippa in their mouths and bite it.

- ↑ Manyura is the Claytonia Ballonensis. (Narrative of the Horn Exped.)

- ↑ Chukuro is in Ngameni "kangaroo," and wola is "nest" or " lair."

- ↑ Tiuba-tiuba and manakata-kata are both lizards.

- ↑ After careful inquiries, it seems that Antiritcha must be supposed to be a hill or mountain, on the upper waters of the Finke River, probably in the M'Donnell Ranges.

- ↑ The belief is that the sky was fastened down to the earth, and that mankind could not walk about freely.

- ↑ Dirpa is subincision, in Dieri called kulpi.

- ↑ Probably the Cucumis trigonus, Linn.

- ↑ Narra is an abbreviation of the Yaurorka word Narrangama, which is a shield, in the Dieri called Pirha mara.

- ↑ Katitandia is Lake Eyre.

- ↑ Mararu is to complete with the hand, to strike the pirha, that is, to strike the upturned wooden bowl, in a dance. Mara is the hand, and ru is the Wonkanguru causative termination, which in the Dieri is li, as mararu, marali. The place Mararu is said by our Wonkanguru informant to be not far from Birdsville, in a south-westerly direction.

- ↑ Kami-mara is the relation which a man bears to all those who are the children of his mother's brother, or of his father's sister. It is remarkable that in this legend the "fathers-in-law" are kami-mara, while with the Wonkanguru, as among the Dieri, it is the mothers-in-law who must be in that relation. Possibly the explanation may be that this legend had its origin in a tribe farther to the north, which like the Arunta has descent counted in the male line.

- ↑ Kandri is a cementing gum prepared from the mindri plant.

- ↑ Ngulyi is the kino of a Eucalypt.

- ↑ Pirha is a bowl, cut out of a block of wood. These natives speak of a thing as being already completed when they have the material ready. Thus a Dieri will say, when he has found a tree suitable for a pirha, "Nauda ngakani pirha," that is my pirha, and similarly as to things such as weapons. In the Waramunga tribe this bowl is called Pitchi.

- ↑ Minka-kadi is a hole or cave, of which there are said to be many, in the district to the east of Mararu.

- ↑ The Kami and Kadi have charge of the boy during the ceremonies, and lead him away after the operation has been performed. The Neyi and the Kaka provide food for him and accompany him. Men of these relationships are always chosen who are much older than he, in order that they may instil respect for the laws which they have to impress upon him. Kadi is the wife's brother, or the sister's husband, which is the same person. Neyi is the elder brother, Kaka is the mother's brother. It must be borne in mind that these are group relations, own and tribal.

- ↑ Kalti is a spear. It appears to be the Nurtunja of Spencer and Gillen, op. cit. p. 122.

- ↑ Such ornaments are given to the boy by his Ngandri.

- ↑ O. Siebert.

- ↑ S. Gason.

- ↑ S. Gason.

- ↑ Karaweli is "boy," and wonkana is "to sing."

- ↑ S. Gason.

- ↑ O. Siebert.

- ↑ S. Gason.

- ↑ O. Siebert.

- ↑ S. Gason.

- ↑ S. Gason.

- ↑ S. Gason.

- ↑ S. Gason.

- ↑ J. G. Reuther.

- ↑ S. Gason.

- ↑ H. Williams.

- ↑ F. Gaskell.

- ↑ Op. cit. pp. 226, 234.

- ↑ There are two bull-roarers, of which the Witarna is the larger one.

- ↑ T. M. Sutton.

- ↑ The Native Tribes of South Australia. Adelaide, 1879.

- ↑ The Narrinyeri. Adelaide, 1847.

- ↑ Wurley is a hut or camp. This word has been carried by settlers all over South Australia.

- ↑ J. W. Boultbee.

- ↑ I observe that Spencer and Gillen, in their new work The Northern Tribes of Central Australia, p. 20, are also of the opinion that "changes in custom have been slowly passing down from north to south."