Natural History, Birds/Accipitres

ORDER I. ACCIPITRES.

(Birds of Prey.)

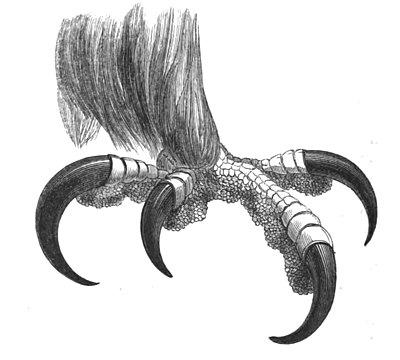

Like the carnivorous quadrupeds, these birds are fitted, by their structure, for a life of rapine. For the most part they feed on living flesh, derived from quadrupeds, birds, reptiles, or fishes, which they pursue and capture by their own strength and prowess. Their natural weapons are not less effective than those with which their mammalian representatives are armed. The beak is strong, crooked, with the point acute and curving downward, and the edges trenchant and knife-like; their feet also are very muscular, and the four toes are armed with powerful talons, long, curved, and pointed, of which those of the hind and innermost toes are the strongest. In the family of the Vultures, however, which feed on the flesh of animals already dead, these characters are much less developed, particularly those which belong to the talons, the true weapons of the more raptorial kinds, the beak being used in both mainly as an instrument of dissecting the food, not of slaying it.

The base of the beak is enveloped in a naked skin, called the cere, in which the nostrils are pierced: the stomach is simple, consisting of a membranous sac without a muscular gizzard. The breast-bone is broad, and in most cases completely ossified, without openings, so as to afford a greater attachment to the muscles of the wings, which are long and powerful. Hence the flight of these birds is usually vigorous, lofty, and long sustained.

FOOT OF EAGLE.

Contrary to what usually prevails among birds, the females in this order are one-third larger than the males. Their eggs are generally pure white, free from spots.

The Accipitres are found in every part of the world. They comprise three well-marked Families, Vulturidæ, Falconidæ, and Strigidæ. Family I. Vulturidæ.

(Vultures.)

We have just observed, that the birds of this Family are not strictly rapacious, inasmuch as their organization unfits them for violence; but their food consists of dead flesh, which in hot countries, where the Vultures chiefly occur, so quickly attains putridity as to have induced the notion that they feed exclusively on carrion. We have proved, however, by personal observation, that decomposition is not a necessary condition of the Vultures' food, for they may be frequently seen regaling themselves on the flesh of an animal within half an hour after it has been killed.

"The Vulturidæ," observes Sir William Jardine, "have universally been looked upon with a kind of disgust. Ungraceful in form, of loose and ill-kept plumage, and except when satisfying the cravings of hunger, or during the season of incubation, of sluggish and inactive manners, they present nothing attractive, while carrion being generally mentioned as their common food, associations have been created of the most loathsome character. They are not, however, without utility, for, in the warmer regions of the world, they consume the animal remains, which, without the assistance of these birds, the more ignoble carnivorous quadrupeds, and the myriads of carcase-eating insects, would soon spread pestilence around."[1]

The beak, in the Vulturidæ is somewhat lengthened, and curved downward at the point: the talons are comparatively weak, and but slightly hooked: the head, and sometimes the neck, in a greater or less degree, are naked, or clothed only with a thin down; as is also the skin that covers the stomach. The wings are powerful and ample, and the general plumage is remarkably stiff and coarse.

The Vultures are widely scattered over the globe, but most abound in the regions that lie between the tropics. There they may generally be seen at all times of the day, soaring on motionless wings at a prodigious elevation, wheeling round in large circles with a peculiarly easy and graceful flight, as they reconnoitre the distant earth below. The senses of sight and smell they possess in great perfection, and notwithstanding the assertions of Mr. Audubon, that the former only is put in requisition by them, there is abundant evidence that these birds are guided to their food by the olfactory organs, as well as by those of vision.

Genus Sarcoramphus. (Dum.)

In this genus, which is confined to America, and comprises but three species, the beak is large and strong; the nostrils are oval, and placed longitudinally at the edge of the cere; the latter, as well as the forehead, is surmounted by a thick and fleshy comb or caruncle; the third quill-feather is the longest; the hind toe is very short.

We illustrate this genus by the far-famed Condor of the Andes, (Sarcoramphus gryphus, Linn.), which, owing to exaggerated reports of its dimensions from the early European travellers, was formerly supposed to be identical with the fabulous Roc, of the Arabian nights, "who, as authors report, is able to trusse an elephant." It is not surprising that this bird, seen in the wildest and most magnificent scenes, far above ordinary objects of comparison, should have drawn upon the imaginations of those who observed it. Nestling in the most solitary places, often upon the ridges

CONDOR.

of rocks which border the lower limits of perpetual snow, and crowned with its extraordinary comb, the Condor, for a long time, appeared to the eyes of the scientific Humboldt, as a winged giant, and he declares that it was not until he had actually measured a dead specimen, that the optical illusion was corrected. Still it is an immense bird: there seems no doubt that individuals have actually been measured, the expanse of whose wings reached to eleven feet, and whose length from beak to tail was between three and four feet. The general colour of the Condor is a glossy black, but the greater part of the wing in the male is white, as is a ruff of soft loose feathers that encircles the base of the neck. The naked skin of the head and neck is of a purplish-red hue; and the greater portion of the beak is white.

In that lofty mountain range which runs through the whole length of South America, whose inaccessible summits are covered with perpetual snow, even beneath a vertical sun, the Condor delights to dwell, fixing his habitation in solitary grandeur at the height of 10,000 or 15,000 feet above the level of the sea. Here they are to be seen in pairs, or groups of three or four, but never associate in large numbers, like the other Vultures. It does not confine itself to dead animals to satisfy its appetite. Mr. Darwin observes, that it will frequently attack living goats and lambs; and two of them are said to unite their efforts even upon creatures so powerful as the llama, or even the puma, which they succeed in destroying. Its strength is very great, as is also its tenacity of life.

The graceful motions of these Vultures in the air, are thus graphically described by Mr. Darwin:—"When the Condors in a flock are wheeling round and round any spot, their flight is beautiful. Except when rising from the ground, I do not recollect ever having seen one of these birds flap its wings. Near Lima, I watched several for nearly half an hour, without once taking off my eyes. They moved in large curves, sweeping in circles, descending and ascending without once flapping. As they glided close over my head, I intently watched from an oblique position the outlines of the separate and terminal feathers of the wing; if there had been the least vibratory movement, these would have blended together, but they were seen distinct against the blue sky. The head and neck were moved frequently, and apparently with force; and it appeared as if the extended wings formed the fulcrum on which the movements of the neck, body, and tail acted. If the bird wished to descend, the wings were for a moment collapsed; and then when again expanded with an altered inclination, the momentum gained by the rapid descent seemed to urge the bird upwards, with the even and steady movement of a paper kite. In the case of any bird soaring, its motion must be sufficiently rapid, so that the action of the inclined surface of its body on the atmosphere may counterbalance its gravity. The force to keep up the momentum of a body moving in a horizontal plane in that fluid (in which there is so little friction) cannot be great; and this force is all that is wanted. The movement of the neck and body of the Condor, we must suppose, is sufficient for this. However this may be, it is truly wonderful and beautiful to see so great a bird, hour after hour, without any apparent exertion, wheeling and gliding over mountain and river."

Mr. Darwin supposes that the Condor breeds only once in two years, that it lays two large white eggs on the bare rock, and that the young are very long in coming to maturity. Family II. Falconidæ.

(Falcons.)

The structure and habits of the Falcons display the highest development of the destructive faculty. The feet are eminently formed for striking and trussing, and the beak for dissecting their prey, which, with scarcely an exception, consists of living animals; and for the pursuit and conquest of, these, the birds before us are endowed with vigorous limbs; the wings being for the most part long, dense, and capable of powerful flight, and the feet strong and muscular, and armed with formidable talons. In almost all cases they obtain their prey by the exercise of their own energies, either striking it down upon the wing, or pouncing upon it on the ground: all the vertebrated animals that they can overcome and kill are their victims, though some species are more restricted in their choice than others, and a few even feed upon large insects. In a state of freedom no rapacious bird would eat any other than animal food, and if it were placed in circumstances where this could not be obtained, it would probably die of hunger, rather than voluntarily have recourse to any other diet. Yet the experiments of John Hunter prove that there is no physical impossibility in the case. "That the Hawk-tribe can be made to feed upon bread, I have known," says that distinguished anatomist, "these thirty years; for to a tame Kite I first gave fat, which it ate readily; then tallow and butter; and afterwards small balls of bread rolled in fat or butter; and by decreasing the fat gradually, it at last ate bread alone, and seemed to thrive as well as when fed with meat. . . . . Spallanzani attempted in vain to make an Eagle eat bread by itself; but by enclosing the bread in meat, so as to deceive the Eagle, the bread was swallowed and digested in the stomach."[2]

The characters of this Family may be thus expressed:—The head is wholly clothed with feathers, except the cere at the base of the beak. The beak is strong, hooked, and, in the more typical genera, furnished with a sharp projection or tooth on each side. The nostrils are more or less rounded, and pierced in the sides of the cere. The eyebrow, in most instances, projects and overhangs the eye; imparting an expression of sternness to the countenance. The outer toe is to some extent connected with the middle toe, and all are armed with strong, very sharp, and much curved talons, the points of which are preserved from injury by a mechanism for elevating them from the surface on which the bird rests; a process analogous to the sheathing of the claws in the Felidæ.

In general the female is much larger than the male adult; and the plumage of the young bird often differs greatly from that of mature age; both of which circumstances have tended not a little to introduce confusion into the natural history of this Family. The members composing it are widely scattered over the globe; and several species have been reclaimed, and trained to pursue their game at the command of man. The amusement of falconry occupied a very large share of the attention of Europe during the middle ages.

Genus Aquila. (Briss.)

We select the Eagles as the representatives of the Falconidæ not because they possess the family characters in the highest degree of development, a distinction which belongs to the genus Falco, but because their great size and strength, combined with somewhat of grandeur and dignity in their aspect, movements, and habits, have, in all ages and countries, given them a place of high consideration among birds.

This genus is characterized by having the beak somewhat lengthened, somewhat angular above, straight at the base, but much curved towards the tip: the notch or tooth of the upper mandible is almost obliterated; the nostrils are oval, and placed transversely; the cere is somewhat rough; the wings have the fourth and fifth quills the longest; the feet are stout and powerful, the tarsi feathered to the toes; the claws are remarkably strong and curved, the under surface grooved; the hind and outer claws longest.

The Eagles are widely scattered. They are birds of lofty and powerful, but not rapid flight. From the latter circumstance, they usually prefer to strike their prey on the ground, the weight of their bodies rendering them unfitted for pursuing a flying prey through its quick and tortuous evolutions. They breed in solitude, on the inaccessible crags of precipitous mountains.

The Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos, Linn.) is the noblest species of the whole Family, for size, strength, and courage. It has been esteemed

GOLDEN EAGLE.

by nations widely separated as the emblem of majesty and power: the might of the Babylonian empire was described under this image in Sacred Prophecy;[3] the iron legions of Rome in ancient, and the veterans of Napoleon in modern times, have fought and conquered beneath their eagle-standards; while at this day the Highland chieftain and the Indian Sagamore alike glory in the eagle's plume as the most honourable ornament with which they can be adorned.

This magnificent bird is about three feet in length; its plumage is of a deep and rich umber-brown, glossed on the back and wings with purple reflections; the feathers of the head and neck are narrow and pointed, of an orange-brown hue, and when shone upon by the sun, have a brilliant, almost golden appearance. The tail is barred with grey and obscure brown; but, in youth, the basal portion of the tail is white, with the tip dark brown; and in this plumage it has been often described as a distinct species, by the name of the Ring-tailed Eagle.

The Golden Eagle is found throughout the middle and north of Europe, and also in North America: in the highest mountain ranges of our own country it was formerly much more common than it is now; but in the wildest parts of the Scottish Highlands it is still a frequent ornament of their sublime scenery. The ravages committed among the flocks at lambing time, when the Eagles have young to feed, have, however, made the destruction of these noble birds an object of constant effort. In the three years ending March, 1834, one hundred and seventy one old Eagles, besides fifty-three young and eggs, were destroyed in the county of Sutherland alone, so that their numbers must be rapidly diminishing. In Ireland it appears to be still numerous; and Mr. Thompson enumerates several situations known as the eyries or breeding-places of this species.

"The eyry," observes Sir William Jardine, "is placed on the face of some stupendous cliff situated inland; the nest is built on a projecting shelve, or on some stumped tree that grows from the rock, generally in a situation perfectly inaccessible without some artificial means, and often out of the reach of shot either from below or from the top of the precipice. It is composed of dead branches, roots of heather, &c., entangled strongly together, and in considerable quantity, but without any lining in the inside; the eggs are two in number, white, with pale brown or purplish blotches. During the season of incubation, the quantity of food that is procured and brought hither is almost incredible; it is composed of nearly all the inhabitants, or their young, of those wild districts called forests, which, though indicating a wooded region, are often tracts where, for miles around, a tree is not seen. Hares, lambs, and the young of deer and roebuck, grouse, black-game, ptarmigan, curlews, and plovers, all contribute to the feast."

In the technical language of falconry, the Eagle was considered "ignoble," as not being capable of training for service in that sport. But the following interesting note, by Mr. Thompson, proves that however savage and indocile it may be when caught in adult age, the Eagle is not difficult to be reclaimed, if trained from the nest:—"My friend Richard Langtry, Esq., of Fortwilliam, near Belfast, has at present a Golden Eagle, which is extremely docile and tractable. It was taken last summer from a nest in Invernesshire, and came into his possession about the end of September. This bird at once became attached to its owner, who, after having it about a month, ventured to give it its liberty, a privilege which was not on the Eagle's part abused, as it came to the lure whenever called. It not only permits itself to be handled in any way, but seems to derive pleasure from the application of the hand to its eggs and plumage. The Eagle was hooded after the manner of the hunting-hawks for some time, but the practice was abandoned; and although it may be requisite, if the bird be trained for the chase, hooding is otherwise unnecessary, as it remains quiet and contented for any length of time, and no matter how far carried on its master's arm. It is quite indifferent to the presence of any persons who may be in his company, and is unwilling to leave him even to take a flight, having to be thrown into the air whenever he wishes it to do so. When this Eagle is at large he has only to hold out his arm towards it, which, as soon as perceived, even at a distance, it flies to and perches on. I have seen it thus come to him not less than a dozen times within half an hour, without any food being offered."[4]

Family III. Strigidæ.

(Owls.)

With the general structure and anatomy resembling those of the Falconidæ, we find in the birds about to be considered, striking modifications in external characters, fitting them for activity during the diminished light of the dusk or night. They have the head very large, with great, dilated, and projecting eyes, looking forwards, each surrounded by a concave disk formed of singular diverging feathers. Behind these disk-feathers is the opening of the ear, which in these birds is of immense size, and of elaborate construction. If we separate the feathers that form the hinder part of the disk, we shall expose the great ear enclosed between two valves of thin skin, from whose edges these feathers grow, and which are capable of being widely opened at the will of the bird, to catch every sound that may give notice of its prey amidst the silence and darkness. The plumage is lax and downy, a character that extends even to the wing-quills; whence the flight of the Owls is unattended with any sound produced by the striking of the air. Even the outer primary has the barbs of its edge separated like the teeth of a saw, allowing a passage to the air. The colours of the plumage are, for the most part, sombre, consisting of various tints of dull yellow, and brown, or white; often spotted, or minutely and most delicately pencilled: a peculiarity of coloration that we find in most nocturnal birds, and, by a beautiful analogy, in the moths and sphinges among Insects.

Mr. Yarrell observes, that from the loose and soft nature of the plumage in these birds, as well as their deficiency in muscle and bone, rapid flight is denied them as useless, if not dangerous, from the state of the atmosphere at the time they are destined to seek their food; but that they are recompensed for this loss, partly by their acute sense of hearing, from the structure of the ear and the size of its orifice, and partly by the beautifully serrated outer edge of the wing-primaries; which, allowing them to range without noise through the air, enables them to approach unheard their unsuspecting victim, which falls a prey to the silent flight and piercing eye of an inveterate enemy.[5]

Some of the species are distinguished by having a series of feathers more or less lengthened, on each side of the top of the head, which can be erected at pleasure; when raised they have a very distant resemblance to horns, or to the erect ears of a cat, and hence these species are familiarly spoken of as horned or eared Owls.

Owls are dispersed over all parts of the globe; and several of the species enjoy a wide geographical range.

Genus Strix. (Linn.)

This genus, which is considered as exhibiting the peculiarities of the nocturnal birds of prey in the highest degree of development, is well illustrated by the most common British species of the Family, the White, or Screech Owl. Several species, very slightly differing from this, are found in various parts of the world, which may be characterized as having the head very large, without any tufts of erectile feathers, but with the face-disks very complete, and of great width; their extent is marked by dense semicircles of rigid narrow feathers, forming a sort of collar, with turned ends, lying close upon each other in the manner of scales. The orifice of the ear, which is within this collar, is also large, as is the ear-flap (operculum). The beak is lengthened and curved only towards the point. The tarsi (or that part of the foot which is raised, commonly, but erroneously, called the leg) are rather long, and feathered; the toes are clothed with hairs.

The Owls of this genus are eminently nocturnal; their enormous facial disks, and great black eyes with dilated pupils, give them a very peculiar appearance; their colours are generally white and pale buff, marked and speckled with bluish-grey. Their voices are loud and discordant.

SCREECH OWL.

The Screech Owl (Strix flammea, Linn.), called also the Barn Owl, is common throughout the British islands, and is spread over Europe, with the exception of the extreme northern regions. Though viewed with some prejudice, it is a very useful bird, preying nearly, if not quite, exclusively, on the small quadrupeds, rats, mice, and voles, that are so annoying and injurious by their depredations. Its habit of retiring into holes and crevices by day occasionally leads it to resort to the pigeon-house, the little caverns of which must present an inviting appearance to this darkness-loving bird; hence it is often accused of preying upon the young pigeons, and crimes are laid to its charge which have been really committed by other birds, or by rats. Mr. Waterton observes, that "if this useful bird caught its food by day, instead of hunting for it by night, mankind would have ocular demonstration of its utility in thinning the country of mice, and it would be protected and encouraged everywhere. When it has young it will bring a mouse to the nest every twelve or fifteen minutes; . . . formerly I could get very few young pigeons till the rats were excluded from the dove-cot; since that took place it has produced a great abundance every year, though the Barn Owls frequent it, and are encouraged all round it;" and he adds, that the pigeons do not regard it "as a bad or suspicious character."

Mr. Thompson, in a pleasing account of a Barn Owl that had built in a dove-cot, confirms this view of its innocence and usefulness. "The White Owl," he observes, "is a well-known visitor to the dove-cot, . . . . and in such a place, or rather a loft appropriated to pigeons, in the town of Belfast, . . . . a pair once had their nest. This contained four young, which were brought up at the same time with many pigeons. The nests containing the latter were on every side, but the Owls never attempted to molest either the parents or their young. As may be conjectured, the Owl's nest was frequently inspected during the progress of the young birds; on the shelf beside them, never less than six, and often fifteen mice and young rats (no birds were ever seen;) have been observed; and this was the number they had left after the night's repast. The parent Owls, when undisturbed, remained all day in the pigeon loft."[6]

The food of the Owl is generally swallowed whole; and the bones and hair, and other indigestible parts are afterwards rejected through the throat, pressed into hard and dry pellets. In places where a pair of Owls have long been accustomed to resort, these castings accumulate in vast heaps.

Like others of this Family, the White Owl is remarkable for the harshness of its voice. During flight it will occasionally utter frightful screams. Mr. Yarrell says that it does not generally hoot; but Sir William Jardine, who shot one in the act of hooting, asserts, that at night, when not alarmed, hooting is its general cry. It also snores and hisses, and when annoyed, snaps its beak loudly.

The White Owl lays five or six eggs, but not all at once, for she lays after some young are already hatched; so that young birds, advanced eggs and fresh-laid eggs may be frequently found in the same nest. The eggs are as large as those of a hen, of a rounded form and pure white.

- ↑ Nat. Lib.—Ornithology, vol. i. p. 91.

- ↑ Animal Œconomy

- ↑ See Jer. xlviii. 40, xlix. 16; Ezek. xvii. 3, &c.

- ↑ Mag. Zool. and Bot. ii. 46.

- ↑ Zool. Journ. vol. iii.

- ↑ Mag. Zool. and Bot. ii. 178.