Natural History, Birds/Anseres

ORDER VIII. ANSERES.

(Web-footed Birds.)

This, the last Order of Birds, is very extensive, and widely distributed. As the waters, of which these birds may, generally, be considered as the inhabitants, possess in the different regions of the globe much more in common than the land, we might expect to find their tenants, to a considerable extent, manifesting a similar community. Nor is this expectation found to be groundless, for, not only are the genera represented by peculiar species in all countries and upon all coasts, but very many even of the species in this Order are found to be truly cosmopolite, many of the Ducks, the Terns, and the Petrels completely circling the globe.

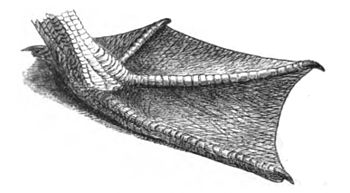

With the trifling exception of the Grebes, which have their feet formed somewhat like that of the Coot, in the last family, the whole Order before us is well marked by having the toes united to each other by a membrane stretched between them, whereby the foot acquires the form of a powerful oar, and of which a familiar example will occur to every reader, in the common Duck or Goose. In addition to this, the feet are placed far back on the body, especially in those species most eminently aquatic, a structure which, while it renders the gait of these birds awkward and shuffling on land, gives to the backward stroke of the foot in the water an impetus, which is very advantageous in swimming. The tarsus is commonly flattened sidewise, that less resistance may

FOOT OF PELICAN.

The form of the body is flattened, not however laterally as in the Waders, but horizontally, the better to float on the surface; the breast-bone is very long, affording a bony protection to the greater portion of the intestines. The plumage is remarkably thick and close, particularly on the under parts of the most aquatic kinds; besides which the skin is furnished with a dense coat of soft down. The outer surface of the plumage is in general polished and satiny, having the property (perhaps from being anointed with an oily secretion frequently applied by the beak) of throwing off water unwetted. The secretion of fat in most of these birds is copious, and it is peculiarly oily in its character. They are the only birds, as Cuvier remarks, in which the neck is longer than the legs, which is sometimes the case to a considerable extent, for the purpose of enabling them to search for food in the depths below, while they swim on the surface. The tail is commonly very short, as are also the wings; hence flight is feebly performed; and in some genera is altogether denied. It must, however, be observed, that in this Order are found the longest wings and the highest powers of flight of the whole class, in the Frigate Pelican; the Petrels and the Terns also are remarkable for their great length of wing: it is remarkable that all these birds, though web-footed, are never seen to swim, though some of them dive or rather plunge with facility.

The flesh of many of the species is extensively used and esteemed as the food of man; that of some, with their eggs, forming a main source of support to many hardy islanders. A few species have been domesticated in our waters and our poultry-yards.

Fens and morasses, broad rivers, and inland lakes, creeks, and estuaries, rocky coves, and muddy bays, precipitous islets and ledgy cliffs, the sinuous coasts of continents and islands, and the broad expanse of the horizon-bound ocean, are the resorts of the web-footed fowl. They are more numerous, particularly the marine kinds, in the colder seas both of the north and south, than in the tropical regions. Our own islands possess a very large number, almost one-third of the species marked as British belonging to this Order.

On this subject, and on the seasonal resorts and habits of these tribes we cannot refrain from presenting to our readers the following charming pictures geographically drawn by Sir William Jardine. After noting the great proportion borne by this Order in the British Fauna, and remarking, that while thousands in summer seek our precipitous coasts and headlands as breeding stations, others, scarcely less numerous, flock in winter to our bays and marine inlets,—he thus proceeds:—

"The contrast of these localities at the different seasons is most striking: rocks standing far in the ocean's void, and precipices of the most dizzy height, to which all approach by land is cut off, possess a dreary solitude for seven or eight months of the year; a few Cormorants seeking repose during the night, or some Gulls claiming a temporary shelter or resting-place from the violence of the storm, are almost the only, and then but occasional, tenants. In the throng of the season of breeding, a very different picture is seen: the whole rocks, and sea, and air, are one scene of animation, and the various groups have returned to take up their old stations, and are now employed in all the accessories of incubation, affording lessons to the ornithological student he will in vain look for elsewhere. The very rocks are lighted up, and would seem to take a brightness from the hurry around, while the cries of the inhabitants, alone discordant, harmonise with the scene.

"During the same season, upon the low sandy or muddy coasts, or extensive meres, where the tide recedes for miles, and the only interruption on the outline is the slight undulation of some mussel-scalps, the dark colour of some bed of zostera contrasting against the long bright crest of the surf, or in the middle distance some bare posts set up as a land-mark, or the timbers of some ill-fated vessel rising above the quicksand,— there reigns, on the contrary, a solitude of another kind; it is now broken only by the distant roll of the surf, by the shrill pipe of the Ring-dotterel, or the glance of its flight as it rises noiselessly; a solitary Gull or Tern that has lagged from the flock may sail along, uttering, as it were, an unwilling inward sound as it passes the intruder; every thing is calm and still, the sensation increased by the hot glimmer that spreads along the sands; there is no voice, there is no animal life. During winter the scene may at first sight appear nearly similar; the warm and flickering haze is changed for a light that can be seen into; the noise of the surge comes deeper through the clear air of frost, and with it at intervals hoarse sounds and shrill whistles, to which the ear is unaccustomed; acres of dark masses are seen, which may be taken for low rocks or scalps, and the line of the sea in the bays contains something which rises and falls, and seems as if it were about to be cast on shore with every coming swell. To the old sportsman all these signs are familiar, and he knows their meaning; but to one who has for the first time trodden these flat coasts, some distant shot or other alarm first explains every thing. The line of the coast is now one dark moving mass; the air seems alive with water-fowl, and is filled with sounds that rise and fall, and vary as the troops wheel around; and this continues until they have again settled to their rest. As dusk approaches these sounds are gradually resumed, at first coming from the ground, as warnings that it is time to be alert; as the darkness and stillness of night sets in, one large flock after another hastens to its feeding-ground, and the various calls and the noise of wings is heard with a clearness which is sufficient to enable the sportsman to mark the kinds and trace his prey to their feeding-stations, to make him aware of their approach long before they come within his reach."[1]

This Order comprises the following six Families,—Anatidæ, Colymbidæ, Alcadæ, Procellariadæ, Laridæ, and Pelecanidæ.

Family I. Anatidæ.

(Ducks.)

The beak in this great Family is thick, broad, high at the base, covered throughout almost its whole length with a soft skin, the tip alone being horny (the former supposed by some to be analogous to the cere, and the small nail-like tip to correspond to what in other birds would be the true horny beak); the edges are cut into a number of thin parallel ridges, or small teeth: the tongue is large and fleshy, with its edges toothed. The wings are in general moderately long. The males have, for the most part, the windpipe enlarged, near the point of its division, into a bony chamber, or capsule, differing in form and size; and some have this tube much prolonged, and bent back in winding folds within the swollen keel of the breast-bone: both of these peculiarities of structure have probably a connection with the loudness or intonation of the voice. The gizzard is large and muscular, and especially in those species which are more terrestrial, living largely on grain. They mostly nestle on the ground, but some on trees, and lay numerous spotless eggs; the young are at first covered with down, and are able to run and to swim as soon as they are hatched.

The remarkable laminated structure at the edges of the mandibles in the birds of this Family, and its connection with their habit of feeding, are thus commented on by Mr. Swainson. "The inconceivable multitudes of minute animals, which swarm in the northern seas, and the equally numerous profusion inhabiting the sides of rivers and fresh waters, would be without any effectual check upon their increase, but for the Family of the Ducks. By means of their broad beak, as they feed upon very small and soft substances, they capture, at one effort, considerable numbers. Strength of substance in this member is unnecessary; the beak is therefore comparatively feeble, but great breadth is obviously essential to the nature of their food. As these small insects, also, which constitute the chief food of the Anatidæ, live principally beneath the surface of the mud, it is clear that the beak should be so formed as that the bird should have the power of separating its nourishment from that which would be detrimental to the stomach. The use of the laminæ thus becomes apparent; the offensive matter is ejected between their interstices, which, however, are not sufficiently wide to admit the passage of the insect-food at the same time. The mouthful of stuff brought from the bottom is, as it were, sifted most effectually by this curiously shaped beak; the refuse is expelled, but the food is retained. It is probable, also, that the tongue is materially employed on this process; for unlike that of all [most] other birds, it is remarkably large, thick, and fleshy."[2]

BEAK OF DUCK.

Genus Anas. (Linn.)

Mr. Yarrell gives the following as the characters of the genus Anas, in which, however, he includes several species that are separated by other ornithologists. The beak about as long as the head, broad, depressed, the sides parallel, sometimes partially dilated; both mandibles furnished on the inner edges with transverse lamellæ. The nostrils small, oval, lateral, in front of the base of the beak. The legs rather short, placed under the centre of the body; tarsus somewhat rounded; toes three in front, connected by intervening membrane, hind toe free, without any pendent lobe or membrane. The wings rather long, pointed; the tail pointed or wedge-shaped. The sexes differ in plumage.

The true Ducks, as restricted, are found almost everywhere; and specimens of the same species are received from the most distant regions. The Shoveler (Anas clypeata, Linn.), for example, is found all over Europe, in the United States, at Smyrna, in North-west India, at Calcutta, and Nepaul; it is common in North Africa, and specimens have been brought from South Africa, and from the islands of Japan. The common Wild Duck again (Anas boschas, Linn.), the parent of our domesticated broods, is spread over the whole of the northern hemisphere, in a wild condition.

The plumage of our beautiful Wild Mallard it is scarcely needful to describe; most persons are familiar with his glossy velvet-green head and neck, his collar of white, his breast and back of chestnut, his beauty-spot of shining purple, his black curling tail, and the delicately pencilled scapular-feathers that fall over his wings. It may not be generally known, however, that in the summer months this distinctive gorgeousness of plumage is laid aside, and the Drake appears for a season in the homely brown livery of his mate.

DUCK.

The tame Duck is almost omnivorous; its indiscriminate appetite, and its voracity equal those of the Hog. In a natural state it is little more particular; fishes, and their young fry, or spawn, tadpoles, slugs, water-insects, larvæ, worms, many plants, seeds, and all sorts of grain, are in turn eagerly devoured by it. Its flesh is in high estimation for the table, and various are the stratagems which man puts in requisition to capture by wholesale a bird so greatly prized. The principal of these are the decoys, by which immense multitudes are taken annually in the fenny counties of England. An interesting account of these, accompanied with illustrative engravings, appeared in the "Penny Magazine" for February, 1835. We have not space to describe the details, but some idea may be formed of their effectiveness, as well as of the abundance of this species, from the fact recorded by Pennant, that in one season thirty-one thousand two hundred Ducks were taken in only ten decoys in the neighbourhood of Wainfleet, in Lincolnshire.

The Mallard in a wild state, contrary to the habit of the domestic bird, always pairs: the Duck makes her nest in some dry spot in the marshes, often sheltered by rank herbage, or beneath some low bush; not seldom, however, the nest is built in the branches of a tree, or the head of a pollard, often at a considerable height from the ground; whence the parent is believed to carry down her young ones, one by one, in her beak. The eggs are usually from ten to fourteen in number, of a bluish white hue; when the Duck has occasion to leave them, she covers them carefully with down or other materials.

The Wild Duck is migratory as well as resident with us; those that have bred in this country are reinforced on the approach of winter by immense flocks of this and other species, which wing their way hither from the already frozen lakes and rivers of the more northern latitudes, whither the majority return in spring. Family II. Colymbidæ.

(Divers.)

Much more exclusively aquatic than the Ducks, the Family before us, as their name imports, are remarkable for the readiness and frequency with which they descend beneath the surface of the water, and for the great length of time during which they can remain immersed. They have the beak narrow, straight, and sharp pointed; the head small; the wings short and hollow; the legs, placed very far behind, near the extremity of the body, are flattened sidewise so as to present a thin edge before and behind; the toes armed with broad flat nails. In one genus the toes are united by a membrane, and there is a short tail; in the other two the toes are divided midway to the base, but are margined with broad oval membranes, and there is no vestige of a tail. The latter chiefly affect fresh waters, the former reside upon the ocean.

The backward position of the feet in these birds, while it renders them powerful and fleet swimmers and divers, greatly diminishes their ability for walking. Indeed they scarcely walk at all, for though they can shuffle along awkwardly in an erect position, it is only for a few steps, when they fall down upon their breast, or else remain sitting erect, supported upon their broad feet as a base, the whole tarsus resting on the ground. Their powers of flight are nearly as limited: but under the surface of the water the wings are expanded and used effectually as fins. The plumage is filamentous or downy, but yet remarkably dense and close lying, and has a silvery or satiny gloss, particularly on the under parts of the body.

The food of the Divers consists, according to their size and the situations they frequent, of fishes with their fry and spawn, crustacea, water-insects, tadpoles, and perhaps vegetable substances occasionally. Their geographical distribution is extensive, though the number of known species is small; the Grebes are widely scattered over the fresh waters of the globe, but the Loons are confined to the temperate and arctic oceans and their coasts.

Genus Colymbus. (Linn.)

In the Loons or true Divers, the beak is long, strong, straight, compressed, and pointed; the edges cutting, but not notched: the nostrils, on each side of the base, are perforated, and partly closed by a membrane. The legs axe thin, the tarsi compressed, placed far back, and closely attached to the hinder part of the body; the feet large, amply webbed, the outer toe longest: the hind toe jointed upon the tarsus, small; the wings short, the first quill-feather longest; the tail short and rounded.

The habits of these birds are peculiarly marine; they are at home amidst the desolation of the polar seas, on whose wild and frost-bound shores and islands they rear their young, laying their eggs on the bare ground. The general colours of their plumage are black and white, the latter arranged in beautifully regular rows of spots, which are commonly lost in winter. The largest and finest species is that called the Great Northern Diver, or Loon (Colymbus glacialis, Linn.), a frequent visitor to our coasts. It is larger than a Goose, its head and neck are black, glossed with purple or green; the upper parts of the body and wings black, regularly

NORTHERN DIVER.

marked with spots of white set in rows, large and square on the scapulars, elsewhere small and round. Two bands going partly round the neck and the upper breast are white, with each feather marked with black down the shaft: the under parts are pure white.

The Divers live chiefly at sea, except during the breeding season, and obtain their living by following the shoals of fishes which approach the shallows to spawn, especially the herrings, sprats, &c. These they catch with, great ease and certainty by diving, pursuing their prey with swiftness beneath the surface. Dr. Richardson found the Northern Diver more abundant on the interior lakes of Arctic America than in the ocean; he says it destroys vast quantities of fish. "It takes wing with difficulty, flies heavily, though swiftly, and frequently in a circle round those who intrude on its haunts. Its loud and very melancholy cry, like the howling of the wolf, and at times like the distant scream of a man in distress, is said to portend rain. Its flesh is dark, tough, and unpalatable."

The following interesting account of the manners of this species in captivity is given by Mr. Nuttall of Boston. "A young bird of this species which I obtained in the Salt Marsh at Chelsea Beach, and transferred to a fish-pond, made a good deal of plaint, and would sometimes wander out of his more natural element, and hide and bask in the grass. On these occasions he lay very still, until nearly approached, and then slid into the pond, and uttered his usual plaint. When out at a distance he made the same cautious efforts to hide, and would commonly defend himself in great anger, by darting at the intruder, and striking powerfully with his dagger-like bill. This bird, with a pink-coloured iris, like albinos, appeared to suffer from the glare of broad daylight, and was inclined to hide from its effects, but became very active towards the dusk of the evening. The pupil of the eye in this individual, like that of nocturnal animals, appeared indeed dilatable; and the one in question often put down his head and eyes into the water to observe the situation of his prey. This bird was a most expert and indefatigable diver, and remained down sometimes for several minutes, often swimming under water, and, as it were, flying with the velocity of an arrow in the air. Though at length inclining to become docile, and shewing no alarm when visited, it constantly betrayed its wandering habits, and every night was found to have waddled to some hiding-place, where it seemed to prefer hunger to the loss of liberty, and never could be restrained from exercising its instinct to move onward to some secure or more suitable asylum."[3]

The eggs are two in number, sometimes three, of a dark olive hue, with a few spots of brown; they are about as large as those of a goose.

Family III. Alcadæ.

(Auks.)

The haunts and habits of these singular birds are exclusively maritime; they are oceanic birds formed for diving, living on small fishes obtained in this manner, and on marine crustacea and mollusca. In the Loons we saw the feet removed to the extremity of the body, but these organs were still ample, and were used in the act of diving; in the Auks the tarsi are very short and the feet small; and in progression under water no use whatever is made of the feet, which are held out behind, like those of the Waders in flight; on the other hand, the short wings are used efficiently in these circumstances, like fins; so that the bird may be said literally to fly beneath the surface. "Their movements under water precisely resemble those of the Dyticidæ or common Water-beetles; the principal motion being more or less vertical, instead of horizontal as in the Grebes and Loons; they are therefore, together with the distinct group of Penguins, the most characteristic divers of the Class."[4]

The characters of the Family are, that the beak is varying in length, more or less compressed; the upper mandible curving to the tip, which is sometimes hooked: the wings are generally short, and in some little more than rudimentary; the tail short and graduated; the tarsi short and compressed; the toes entirely webbed, the hind toe either wanting or very small.

These birds frequently associate in immense numbers on rocky islets and precipitous cliffs that overhang the sea, on the shelves and narrow ledges of which they lay their eggs, one only deposited by each bird; the female keeping it between her feet for the purpose of incubation, as she sits in an erect position. The procuring of the eggs and young of these and similar birds, forms an important means of subsistence to many families.

The storm-lashed and iron-bound coasts of Northern Europe and America, and of the extreme southern portion of the latter continent, with the frozen islands of both the Arctic and Antarctic Oceans, are the dreary homes of the birds of this Family; some of which roam hundreds of miles out to sea.

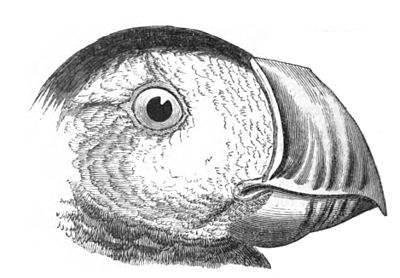

Genus Fratercula. (Briss.)

BEAK OF PUFFIN.

The Puffins are inhabitants of the northern regions, but are migratory visitors to the more temperate regions, keeping near the shore, concealing themselves by night in the clefts of rocks, or in burrows, which they themselves excavate to the depth of a yard or more. In these burrows the female lays a single egg on the bare ground. Their flight is heavy and rather quick, but only sustained for short distances, commonly just above the surface of the water, which they sometimes strike with their feet to acquire an additional impetus. In the water their speed is great, and they dive with great facility. They principally feed on marine mollusca and crustacea, to which small fishes are added.

The Common Puffin or Coulterneb (Fratercula arctica, Linn.) visits the rocky shores of the British Islands in summer, for the purpose of breeding; remaining from April to August. It is a bird of singularly grotesque appearance: its short thickset form, its erect attitude, and above all, its extraordinary beak, grooved over with furrows, and marked with bright colours, give it a very peculiar aspect. It is not much larger than a pigeon, but of stouter form, and with a greater head: the crown, hind head, whole upper parts, and a collar round the neck are black; the sides of the head and face pale grey, the whole under parts pure white: the central portion of the beak is pale blue, the base with the mouth yellow, the grooves and tip orange; the latter is the hue also of the eyelids, and of the legs and feet.

The shallow surface-earth on the summit of the coast-cliffs affords an opportunity to the Puffin to excavate its burrow; but not unfrequently it saves itself some labour by taking possession of the burrow of the rabbit; the formidable beak

PUFFIN

"Many Puffins," observes Mr. Selby, "resort to the Fern Islands, selecting such as are covered with a stratum of vegetable mould; and here they dig their own burrows, from there not being any rabbits to dispossess upon the particular islets they frequent. They commence this operation about the first week in May, and the hole is generally excavated to the depth of three feet, often in a curving direction, and occasionally with two entrances. When engaged in digging, which is principally performed by the males, they are sometimes so intent upon their work as to admit of being taken by the hand, and the same may also be done during incubation. At this period I have frequently obtained specimens, by thrusting my arm into the burrow, though at the risk of receiving a severe bite from the powerful and sharp-edged bill of the old bird. At the farther end of this hole the single egg is deposited, which in size nearly equals that of a Pullet. Its colour when first laid is white, sometimes spotted with pale ash-colour, but it soon becomes soiled and dirty from its immediate contact with the earth, no materials being collected for a nest at the end of the burrow. The young are hatched after a month's incubation, and are then covered with a long blackish down above, which gradually gives place to the feathered plumage, so that, at the end of a month, or five weeks, they are able to quit the burrow, and follow their parents to the open sea."[5]

At the lone island of St. Kilda many of these birds are said to be taken as they sit on the ledges of the rocks, by means of a noose of horse-hair attached to a slender rod of bamboo-cane. This mode is most successful in wet weather, as the Puffins then sit best upon the rocks, allowing a person to approach within a few yards, and as many as three hundred may be taken in the course of one day by an expert bird-catcher. They are sought principally for their feathers,[6] which, like those of all these and similar birds, are copious, soft, and downy; and therefore well adapted for beds.

Family IV. Procellariadæ.

(Petrels.)

The form of the beak in these birds is very remarkable, as it appears to be constituted of several distinct pieces: the upper mandible has the basal portion separated from the tip by a deep oblique furrow, and carrying on its summit, a tube (or two united into one) which contains the nostrils; the point of this mandible takes the form of a curved and pointed claw or nail; the lower mandible is likewise seamed in a similar manner, and its tip is hooked downwards.

The fore-toes are united by a membrane, the hind-toe is rudimentary, and reduced to a mere claw, which is elevated upon the tarsus. The wings are usually long, and the flight powerful.

The Petrels are eminently oceanic birds, wandering over the boundless seas in all latitudes, rarely approaching the land except in the breeding season. Some of them appear as if they were almost constantly on the wing, for they follow the course of ships for many days together, and are never seen to alight on the water, either by day

BEAK OF PETREL.

Genus Thalassidroma. (Vigors.)

In these little birds, the smallest of web-footed fowl, the beak is short, much compressed in front of the nasal tube; the tip of the upper mandible suddenly curving downwards, that of the lower angled and following the curve of the upper. The nostrils contained in one tube, but shewing two orifices. The tarsi long and slender; fore-toes webbed : hind-toe merely a small, dependent nail; the wings long and pointed; the tail square or slightly forked.

Several species seem to have been formerly confounded under the name of the Stormy Petrel, which are now found to be distinct: we select for illustration that known as Wilson's Petrel (Thalassidroma Wilsoni, Bonap.), the most commonly seen in the Atlantic. It is about as large as a Lark; of a sooty black hue, with a broad band of rusty brown across each wing, and one of pure white across the rump; the legs are long, and, with the toes and their membranes, are black, with the centre of the latter pale.

The habits of this species are well described by the admirable ornithologist to whose memory it is dedicated. "In the month of July, on a voyage from New Orleans to New York... on entering the Gulf Stream, and passing along the coasts of Florida and the Carolinas, these birds made their appearance in great numbers, and in all weathers, contributing much, by their sprightly evolutions of wing, to enliven the scene, and affording me every day several hours of amusement. It is indeed an interesting sight to observe these little birds in a gale, coursing over the waves, down the declivities, up the ascents of the foaming surf that threatens to burst over their heads, sweeping along the hollow troughs of the sea, as in a sheltered

WILSON'S PETREL

Wilson appears to have had no knowledge of the domestic economy of this bird, but Audubon informs us that it breeds on some small islands near the southern extremity of Nova Scotia, formed of sand and light earth, scantily covered with grass. Thither the birds resort in great numbers about the beginning of June, and form burrows about two feet deep, in the bottom of which each female lays a single white egg, as large as that of a pigeon, but more oblong. A few pieces of dried grass form the only apology for a nest. The young are able to follow their parents in their seaward flights by the beginning of August.

The present species appears to affect the American more than the European side of the Atlantic Ocean, yet several specimens have been obtained in this country.

Family V. Laridæ.

(Gulls.)

Through the Skuas, which have somewhat of the form of beak we have last described, the passage from the Petrels to the Gulls is easy and obvious. These are, for the most part, birds of large size, in which the swimming and diving structure recedes, and the most prominent actions are those of flying and walking. "The whole of the Family," observes Mr. Vigors, who includes in it the Petrels, "is distinctly characterized by the strength and expansiveness of their wings, with the aid of which they traverse immeasurable tracts of the ocean in search of their food, and support their flight at considerable distances from land, seldom having recourse to their powers of swimming. We may thus discern the gradual succession by which the characters peculiar to the Order descend from the typical groups that swim and dive well and frequently, but make little use of their wings for flight, to the present groups, which are accustomed to fly much, but seldom employ their powers of swimming, and never dive."[8] One can scarcely look at a Gull, without being strongly reminded of the Wading-birds, and particularly the Plovers, to which in general form, in attitude, in the long and slender tarsus, with the hind-toe minute and set high up (as in Vanellus), in the naked space above the heel, and even in the form of the beak, straight, slender, and swelling towards the tip, as well as in their internal anatomy, they shew a manifest approach. The typical Gulls are much more land-birds than any others of their Order: those of the subgenus Xema in particular roam much inland, feed on insects and worms, build their nests among herbage in low meadows near the sea, lay eggs of an olive colour marked with large brown spots, and undergo seasonal changes of plumage; all of which might be predicated of the Charadriadæ.

The characters of the Family may be thus summed up: the beak is slender, compressed, gradually, not abruptly bent; the nostrils pierced in the middle of the mandible: the wings are very long and pointed; the hind toe elevated, very small, and not united by a membrane. The prevailing colour of the plumage is white, often varied on the upper parts by a pearly grey, or black.

These birds are found in all parts of the world, feeding greedily on all kinds of animal substances; others, as already remarked, seek their food in the interior of the land, which consists of slugs, worms, and the larvæ of insects. Some few are bold and cunning, attacking other marine birds, and forcing them to disgorge the fish they have swallowed, which these then snap up before it reaches the sea.

Genus Larus. (Linn.)

In this genus the beak is strong, hard, compressed, cutting, slightly curved towards the point; the lower mandible with a strong angle: the nostrils lateral, near the middle of the beak, pervious. The wings long, pointed; second quill feather longest, but the first nearly equal. The legs set near the middle of the body, slender, naked at the lower part; the tarsi long, palmated, yet formed for walking: the tail square or slightly forked.

One of our most abundant species is the Black-headed, or Laughing Gull (Larus ridibundus, Linn.), the upper parts of whose body are pearl-grey, the lower parts, with the whole neck, pure white; the head, and the tips of the wings black; the beak and feet scarlet.

LAUGHING GULL.

During the summer this Gull frequents marshes and wet meadows, where it produces and brings up its young; in the winter it retires to the shore. Their periodical migrations from the coast to their breeding localities and back, are so regular that they may be calculated on almost to a day.

The food of this species consists of insects, worms, spawn, fry, and small fishes; it has been seen dashing round some lofty elms catching cock-chafers. In spring it follows the plough as regularly as the Rook, and from the great number of worms and grubs which it devours renders no un-important benefit to the farmer. Nor is this the only way in which these birds are useful; for both their eggs and young are valued for the table. Of the former Mr. Selby speaks as being well-flavoured, free from a fishy taste, and when boiled hard, as not easily distinguishable from those of the Lapwing, for which they are sometimes substituted in the market. He adds, that the young are still eaten, though not in such demand as they formerly were, when great numbers were annually taken and fattened for the table, and when a Gullery produced a revenue of from 50l. to 80l. to the proprietor. Willoughby describes one of these colonies, which in his time annually built and bred at Norbury in Staffordshire, in an island in the middle of a great pool. " About the beginning of March hither they come; about the end of April they build. They lay three, four, or five eggs, of a dirty green colour, spotted with dark brown, two inches long, of an ounce and a half weight; blunter at one end . . . When the young are almost come to their full growth those entrusted by the lord of the soil drive them from off the island through the pool into nets set on the banks to take them. When they have taken them they feed them with the entrails of beasts, and when they are fat sell them for fourpence or five-pence a-piece. They yearly take about a thousand two hundred young ones, whence may be computed what profit the lord makes of them. About the end of July they all fly away and leave the island."

Another breeding station, which seems to have been occupied by these birds for more than three hundred years, is described in the "Catalogue of Norfolk and Suffolk birds." "Near the centre of the county of Norfolk, at the distance of about twenty-five miles from the sea, is a large piece of water called Scoulton Mere. In the middle of this mere there is a boggy island of seventy acres extent, covered with reeds, and on which there are some birch and willow trees. There is no river communicating between the mere and the sea. This mere has from time immemorial been a favourite breeding spot of the Brown-headed Gull. These birds begin to make their appearance at Scoulton about the middle of February; and by the end of the first week in March the great body of them have always arrived. They spread themselves over the neighbouring country to the distance of several miles in search of food, following the plough like Rooks. If the spring is mild the Gulls begin to lay about the middle of April; but the month of May is the time at which the eggs are found in the greatest abundance. At this season a man and three boys find constant employment in collecting them, and they have sometimes gathered upwards of a thousand in a day. These eggs are sold on the spot at the rate of fourpence a score, and are regularly sent in considerable quantities to the markets at Norwich and Lynn. . . The young birds leave the nest as soon as hatched, and take to the water. When they can fly well, the old ones depart with them, and by the middle of July they all leave Scoulton. We were a little surprised at seeing some of these Gulls alight and sit upon some low bushy willows which grew on the island. No other than the Brown-headed Gull breeds at this mere; a few of them breed also in many of the marshes contiguous to the sea-coast of Norfolk."

Family IV. Pelecanidæ.

(Pelicans.)

The most characteristic mark of this the last Family of Birds, is, that the hind-toe, which can be brought partially round to point forward, is united to the others by a connecting membrane, so that the whole four toes are webbed. Notwithstanding this structure, which seems to fit them more completely for an aquatic life, most of these birds do not swim or dive at all, but on the other hand, they perch much on trees. They are all good fliers, and some, from the extreme expanse of their wings, have extraordinary powers of flight. They spend a great deal of time upon the wing, some soaring far out over the ocean, or mounting to a most sublime elevation, others beating over a limited space, till the appearance of a fish beneath them arrests their attention, when they plunge down upon it, and instantly rise again into the air.

With the exception of the Phaetons, which have many of the characters of the Laridæ, the members of this Family have more or less naked skin about the face, and on the throat, which latter is dilatable: the tongue is very minute, and the nostrils are mere slits, scarcely or not at all perceptible; in the nestling bird, however, they are open. They all live on fishes, are almost exclusively marine, and nestle and roost either on rocks or on lofty trees: the eggs are encased with a soft, absorbent, chalky substance, laid over the hard shell; the young are at first covered with long and flossy blackish down; they remain long in the nest, and when they leave it, are generally equal, or superior to the adults in weight.

The Pelecanidæ are found in the seas and around the coasts of most parts of the globe: but the species are not numerous. The prevailing colours of their plumage are black, often glossed with metallic reflections, and white.

Genus Phalacracorax. (Briss.)

The Cormorants, to which genus belong two out of the three species of Pelecanidæ that inhabit the British coasts, are distinguished by having the beak long, straight, compressed, the upper mandible terminating in a powerful hook, the base connected with a membrane which extends to the throat, which, as well as the face, is naked. The legs are short, robust, and placed behind the middle of the body: the four toes connected, the hind-toe jointed on the inner side of the tarsus; the outer toe the longest; the claw of the middle toe comb-like on one edge. The wings moderately long, the third quill the longest; the tail stiff and rigid.

These voracious birds are of dark, but often rich colours, they undergo a seasonal change of plumage, and the young differ from the adults. In winter they perform a partial migration inland to the lakes or rivers; they habitually perch on trees, or sit on the ledges of precipitous sea-ward rocks, on which they make large nests and breed. They are susceptible of domestication, and in some countries still, as in our own formerly, are trained to catch and bring in fish.

The Green Cormorant, or Shag (Phalacracorax cristatus, Steph.), is abundantly distributed around the British coast, and that of the north of Europe: it was also found at the Cape of Good Hope by Dr. A. Smith. The adult male in his winter dress has the whole plumage of a rich, dark, and lustrous green; the upper parts finely bronzed, and each feather margined with a border of fine velvety black; the tail is of a dead black; the base of the beak and small throat-pouch are of a fine yellow hue; the iris of the eye clear green. During the spring a fine tuft or crest of wide and outspread feathers, about an inch and a half high, capable of erection, rises from the crown and hind head, which is lost after the breeding season.

The habits of the Shag are decidedly maritime: it rarely quits the sea to follow the course of a river, nor does it perch on trees, like the other Cormorants. It makes a large nest, composed of sea-weed, in the fissures, and on the ledges of rocks; many associating together; Col. Montagu says he has seen thirty nests close together on a small rock. Three or four eggs are laid, as large as those of a hen, of a chalky white surface, varied with pale blue.

SHAG

"The most extensive colony" observes Sir William Jardine, "which has ever come under our observation, is one in the Isle of Man, on the precipitous coast adjacent to the Calf, of such elevation that the centre was out of range, either from the top or from the sea; there they nestled in deep horizontal fissures, conscious apparently of their security, and would poke out their long necks, to ascertain the reason of the noise below, or when a ball struck the rock near them, with the hope of causing them to fly. There were hundreds of nests, and the birds not sitting kept flying in front of the rock, passing and repassing so long as any thing remained to disturb them. On approaching this resort, and also at a similar, but smaller, one on St. Bee's Head, few of the birds quitted the rock ; but at the surprise of our first shots, they fell, as it were, or darted straight to the water, some of them close to the boat, so much so as at first to cause us to think that great havoc had been made ; in which we were soon undeceived, by seeing numerous heads appearing at a distance, and the birds immediately making off in safety. They soon, however, learned to sit and look down in content, though at new stations we procured specimens by one firing at the rock, and another taking the birds as they darted to the water. Caves are also resorted to as breeding places by this bird, on the ledges of which the nest is placed. On the Bass Rock, and the Isle of May, where only a few resort, they select the deep caves : and a boat, stationed at the entrance, but out of sight, may some times procure shots at the disturbed birds flying out, although they more frequently dive into the water of the cave, and swim under until far past the entrance."[9]

As an example of the great depth to which marine diving birds will descend in pursuit of prey, Mr. Yarrell mentions that the Shag has been caught in a crab-pot fixed at twenty fathoms, or one hundred and twenty feet below the surface.

We may here allude to some observations by Colonel Montagu on a Cormorant, which, though not of the present species, was nearly allied ; and with these notes we close our volume on Birds. A specimen of the Great Cormorant (P. carbo, Linn.) kept by him was extremely docile, of a grateful disposition, and by no means of a savage or vindictive spirit. He received it by coach after it had been twenty-four hours on the road; yet though it must have been very hungry, it rejected every sort of food he could offer to it, even raw flesh; but as he could not procure fish at the time, he was compelled to cram it with raw flesh, which it swallowed with evident reluctance, though it did not attempt to strike him with its formidable beak. When removed to the aquatic menagerie, it became restless and agitated at the sight of the water, and when set at liberty plunged and dived without intermission for a considerable time, without capturing or even discovering, a single fish ; when, apparently convinced that there were none to be found, it made no farther attempt for three days.

Colonel Montagu afterwards noticed the dexterity with which it seized its prey. If a fish was thrown into the water at a distance, it would dive immediately, pursuing its course under the surface, in a direct line towards the spot, never failing to take the fish, and that frequently before it reached the bottom. The quantity it would devour was astonishing; three or four pounds twice a-day were swallowed, the digestion being excessively rapid. It lived in perfect harmony with the wild Swan, wild Goose, Ducks of various species, and other birds, but to a Gull with a piece of fish it would instantly give chase; in this it seemed actuated by a desire to possess the fish, for if the Gull had time to swallow it, no resentment was manifested. Apparently the sight of the fish created a desire of possession, which ceased when it had disappeared.[10]

- ↑ Nat. Lib. Ornithology, iv. 456.

- ↑ Journ. Roy. Inst (August, 1831.)

- ↑ Quoted in Yarrell's Brit Birds, iii. 427.

- ↑ Mr. Blyth, in Cuvier's Anim. Kingd. Lond. 1840.

- ↑ Brit. Birds, iii. 470.

- ↑ Macgillivray.

- ↑ Wilson's Amer. Ornith. (Edin. 1831), ill. 166.

- ↑ Linn. Trans, vol. xv.

- ↑ Nat. Lib. Ornithology, iv. 240.

- ↑ Ornith. Dict. 102.