Natural History, Birds/Dentirostres

TRIBE III. DENTIROSTRES.

The upper mandible of the beak in this Tribe is notched on each side near the tip; in one Family, that of the Shrikes, this indentation is very decided, and accompanied with a projecting tooth, so as to present a connecting link with the Accipitres, the beak also being very strong, hooked, and sharp-pointed, and the habits of the birds ferocious and carnivorous. But even in these the notch is confined to the horny exterior of the beak, no trace of it being to be discovered in the bone, from which, on the contrary, the tooth in the beak of the Falcons is a true process. In other Families, the notch becomes very small, so as at length to be scarcely perceptible; and, in fact, the transition from this Tribe to the Tenuirostres on the one hand, and to the Conirostres on the other, is so gradual that the points of separation cannot be determined with precision.

HEAD OF TYRANNUS.

The food of the birds of this Tribe consists very largely of insects, though not a few combine with this diet, berries and other soft fruits. None of them feed on hard seeds, which constitute the principal support of the Conirostres. With the exception of the single Family of the Finches (Fringilladæ) in the Tribe just mentioned, almost all the birds that possess musical notes are found in the Tribe now before us, of which those renowned songsters, the Nightingale of the Old World, and the Mocking-bird of the New, are members.

The Dentirostres are scattered over the whole globe, and are comprised in the following five Families, Sylviadæ, Turdidæ, Muscicapadæ, Ampelidæ, and Laniadæ.

Family I. Sylviadæ.

(Warblers.)

We have here a very extensive and widespread group of small and delicately formed birds, very many of which are noted for their powers of song. Though the habits of so vast a number of species vary considerably, yet in general the Warblers frequent groves and woods, and search for the small insects which constitute their food, among the leaves and twigs, and in the crevices of the bark of trees, rather than on the wing. Mr. Swainson thus describes the habits of these pretty little birds: —"The chief peculiarity which runs through this numerous Family is the very small size and delicate structure of its individuals. Excepting the Humming-birds, we find among these elegant little creatures the smallest birds in the creation. The diminutive Golden-crests, the Nightingale, the Whitethroat, and the Wood-wren, are all well-known examples of genuine Warblers, familiar to the British naturalist. The groups of this extensive Family, spread over all the habitable regions of the globe, are destined to perform an important part in the economy of nature: to them appears intrusted the subjugation of those innumerable minute insects which lurk within the buds, the foliage, or the flowers, of plants, and, thus protected, escape that destruction from Swallows to which they are exposed only during flight. The diminutive size of such insects renders them unfit for the nourishment of the Thrushes and the larger insectivorous birds; while their number and variety only become apparent when the boughs are shaken and their retreat disturbed. How enormous, then, would be their multiplication, had not nature provided other races of beings to check their increase. No birds appear more perfectly adapted for this purpose than are the Warblers." Mr. Swainson goes on to notice the arrival of these birds in spring, when the increasing warmth is calling the insect world into renewed life and activity, and their departure in autumn, when the hosts of minute insects begin to diminish, and no longer require to be kept within bounds. As different localities seem allotted to different tribes of insects, so similar diversity is observable in the haunts of the various groups of Warblers. Thus the Golden-crests and Wood-warblers (Sylvianæ) confine themselves principally to the higher trees, where they search for winged insects among the leaves, or capture them like the Fly-catchers, when attempting to escape. The Reed-warblers and the Nightingales (Philomelinæ) haunt the vicinity of waters, or the more dense foliage of hedges, for insects peculiar to such situations. The Stonechats (Saxicolinæ), on the contrary, prefer dry commons, and wide extended plains, feeding on insects appropriated to those localities; while those insects that affect humid and wet places are the chosen food of Wagtails and Titlarks (Motacillinæ); and, lastly, the Tits (Parirnæ) search assiduously among the buds and tender shoots of trees, thus destroying a multitude of hidden enemies to vegetation.[1]

The birds of this Family have the beak slender, tapering to the point, both of the mandibles having, in most cases, the vertical outline slightly arched, and the lateral outline slightly incurved: the tip is perceptibly notched. Their form is elegant, their plumage fine and close, and their prevailing colours are olive-brown, yellow, and blue, often chastely but beautifully arranged, and sometimes set off with deep black. Their motions are sprightly, but their flight is feeble; yet they are almost all migratory, inhabiting the torrid zone during the winter months, and visiting temperate climates in the spring, where they breed during the summer. We have remarked that most of them are musical, and though of many, the song, if heard alone, would be scarcely thought worthy of admiration, yet, when mingled with many more, each contributes its part to that concert of many notes that fills the groves in spring, and which, though a confused medley of melody, never fails to please, and even charm the auditor.

Genus Philomela.(Swains.)

The generic characters of the Nightingales are the following:— the beak straight, the upper edge rounded, the tip slightly bent, and notched; the wings, with the first quill very short, the third longest; the tarsi rather long, the feet being formed for walking and hopping as well as for perching. The genus is properly European, extending, however, into the western countries of Asia, and into the north of Africa.

The common Nightingale (Philomela luscinia, Linn.), so renowned for its song, even since the

NIGHTINGALE.

time of Homer, is of very plain and unobtrusive plumage. The upper parts are yellowish-brown, tinged with reddish on the crown, as well as on the rump and tail; the under parts greyish-white, purest on the middle of the belly; the beak and feet pale brown.

Though on the continent the Nightingale visits Sweden, Russia, and even Siberia, yet it does not spread itself over Great Britain. In the south and east of England it is common, from April to September, but does not extend beyond Dorsetshire westward, nor beyond Yorkshire northward. In Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, it is unknown. "Why they should not be found," remarks Montagu, "in all the wooded parts of Devonshire and Cornwall, which appear equally calculated for their residence, both from the mildness of the air and variety of ground, is beyond the naturalist's penetration. The bounds prescribed to all animals, and even plants, is a curious and important fact in the great works of nature. It has been observed that the Nightingale may possibly not be found in any part but where cowslips grow plentifully; certainly, with respect to Devonshire and Cornwall, this coincidence is just."

An attempt made to introduce this admired bird into Scotland, though well conducted, failed of success. Sir John Sinclair, impressed with a notion generally possessed, that the migratory songsters, both old and young, return to their native haunts, season after season, procured as many Nightingales' eggs as he could purchase in Covent Garden market at a shilling each. The eggs being carefully packed in wool, were safely transmitted to Scotland by the mail. Sir John had employed men to discover and watch the nests of several Robins, in places where the eggs might be deposited and hatched in security. The Robins' eggs having been removed, were replaced by those of the Nightingales, which all, in due time, were hatched, and the young brought up by their foster-parents until fully fledged. After they had flown, the introduced songsters were observed for some time about the vicinity; but in September, the usual period for the departure of the species, they disappeared, and never returned to the place of their birth.

The like disappointment attended a similar essay to introduce the species into South Wales. A few years ago a gentleman of Gower, the peninsula beyond Swansea, procured some scores of young Nightingales from Norfolk and Surrey, "hoping that an acquaintance with his beautiful woods and their mild climate would induce a second visit, but the law of nature was too strong for him, and not a single bird returned."[2]

Like most of our summer visitors, the male Nightingales arrive in their migration several days before the females, and commence their song immediately. The London bird-catchers are doubly diligent at this time, aware that the males captured after they have obtained mates either do not survive the confinement, or at least continue silent. It frequents the hedge-rows and copses rather than the large woods; around London, the extensive grounds of the market-gardeners are favourite resorts with it. The nest is built either on or near the ground, among decaying leaves, and is rather loosely constructed of dried grass and slender root-fibres. The eggs are of an uniform olive hue, without spots: the young, in their first plumage, are mottled, as in the Thrushes. The song of the parents ceases as soon as the young are hatched, early in June.

The melody of the Nightingale, uttered as it is, though not exclusively, during the solemn stillness of the balmy night, has been almost universally admired; but whether the notes are plaintive and melancholy, or cheerful and sprightly, opinions are divided. The former epithets are the most commonly applied to them, especially by the poets, who were perhaps influenced by their classic recollections. As an example of the latter judgment, Coleridge may be quoted:—

"A melancholy bird! O idle thought!

In nature there is nothing melancholy:

But some night-wandering man, whose heart was pierced

With the remembrance of a grievous wrong,

Or slow distemper, or neglected love,

(And so, poor wretch! fill'd all things with himself

And made all gentle sounds tell back the tale

Of his own sorrow,) he, and such as he,

First named these notes a melancholy strain,

And many a poet echoes the conceit.

We have learnt

A different lore: we may not thus profane

Nature's sweet voices, always full of love

And joyance! Tis the merry nightingale

That crowds, and hurries, and precipitates

With fast thick warble his delicious notes,

As he were fearful that an April night

Would be too short for him to utter forth

His love-chant, and disburthen his full soul

Of all its music! ......

....Far and near

In wood and thicket over the wide grove

They answer and provoke each other's songs,

With skirmish and capricious passagings,

And murmurs musical, and swift 'jug, jug,'

And one low piping sound more sweet than all,

Stirring the air with such a harmony,

That should you close your eyes you might almost

Forget it was not day." [3]

But perhaps these opinions are not irreconcileable; for, as the Abbé La Pluche says, "the Nightingale passes from grave to gay, from a simple song to a warble the most varied, and from the softest trillings and swells to languishing and lamentable sighs, which he as quickly abandons, to return to his natural sprightliness." [4]

A notion has long prevailed that the song of the Nightingale is heard to most advantage in the east, and that it declines in sweetness and richness in proportion as it is found farther to the north and west. Thus the Nightingales of Persia, Turkey, and Greece are said to be more melodious than those of Italy, while the Italian birds are esteemed by amateurs superior to those of France; and these last to those of England. The London fanciers prefer those of Surrey to those taken north of London. Yet, perhaps, this superiority is more fancied than real; and certainly not constant, if we receive the testimony of one familiar with the melody of birds. "In 1802," observes Mr. Syme, "being at Geneva, at the residence of a friend, about three miles from the town, in a quiet, sequestered spot, surrounded by gardens and forests, and within hearing of the murmur of the Rhone,—there, in a beautiful still evening, the air soft and balmy, the windows of the house open, and the twilight chequered by trees, there we heard two Nightingales sing, indeed, most delightfully,—but not more so than one we heard down a stair, in a dark cellar, in the High Street in Edinburgh! such a place as that described in 'The Antiquary;' no window, and no light admitted, but what came from the open door, and the atmosphere charged with the fumes of tobacco and spirits; (it was a place where carriers lodged, or put up,) and the heads of the porters and chairmen, carrying luggage, nearly came in contact with the cage, which was hung at the foot of the staircase;—yet even here did this bird sing as mellow, as sweet, and as sprightly as did those of Geneva. We have often stopped to hear it, and listened with the greatest pleasure, and as the pieman passed with his jingling bell, a sound now seldom heard in the streets of Edinburgh, the bird seemed more sprightly, and warbled with renewed spirit and energy."[5]

Genus Motacilla. (Linn.)

The great extent of the Family Sylviadæ induces us to illustrate it by another form, the habits of which differ much in detail from those of the more typical Warblers. The Wagtails have been briefly but graphically described as "an active graceful race, tripping it along the smooth-shaven grass-plots, edges of ponds, and sandy river-shores in unwearied search for their insect food, and with tails which never cease to vibrate as long as their restless little bodies are in action.

The genus Motacilla, as now restricted to the Wagtails, is characterized by the beak being slender, nearly straight, slightly entering among the feathers of the forehead; the gape smooth; the wings with the first and second quills longest, the tertiary feathers greatly lengthened, extending nearly to the tip of the closed wing, a peculiarity of such birds, of various Orders, as haunt the borders of shallow water; the legs and feet long, particularly the tarsi; the tail very long, and incessantly in motion up and down. Their colours are chiefly black, white, grey, and yellow, arranged in masses with strong contrasts.

The true Wagtails are well known as the regular frequenters of the marshy meadow, the grassy banks of the placid river, or the pebbly margin of the brawling brook; the roaring mill-stream of the village is attended by its little group of "Dishwashes," as the country swains term them, and others run hither and thither among the rocks that border the lonely mountain torrent. They wade into the shallows to pick up water-insects and their larvae, as well as small pond-snails and other mollusca, run at flies that are resting on the herbage, and pursue with a short low flight such as they arouse to take wing. "When the cows are feeding in the moist low pastures," says White of Selborne (and every one must have seen the observation confirmed), "broods of Wagtails, white and grey, run round them, close up to their noses, and under their very bellies, availing themselves of the flies that settle on their legs, and probably finding worms and larvae that are roused by the trampling of their feet. Nature is such an economist, that the most incongruous animals can avail themselves of each other! Interest makes strange friendships."

Four or five species are found with us, of which the Pied Wagtail (Motacilla Yarrellii, Gould) is the most abundant. Its colours are chiefly black and white; the former spreading over the upper parts, and forming a large patch on the throat and breast: the latter being the hue of the forehead, sides of the head and neck, the lower parts, and the external feathers of the tail. In winter the black patch on the breast becomes much smaller, and the back turns grey.

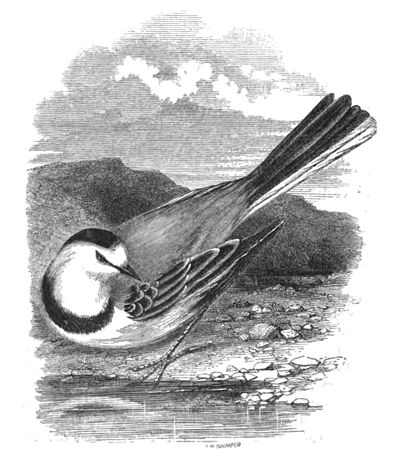

PIED WAGTAIL.

The Pied Wagtail is found in all parts of the British islands, subject to a partial migration, on the approach of winter, towards the more southern counties. On the continent it seems confined to Sweden and Norway, being replaced in the central and more temperate parts by a species closely resembling it, Motacilla alba, (Linn.) The eminent zoologist after whom our species has been named, thus describes its manners, in his "British Birds:" "It is ever in motion, running with facility by a rapid succession of steps in pursuit of its insect-food, moving from place to place by short undulating flights, uttering a cheerful chirping note while on the wing, alighting again on the ground with a sylph-like buoyancy, and a graceful fanning motion of the tail, from which it derives its name. It frequents the vicinity of ponds and streams, moist pastures, and the grass-plots of pleasure grounds; may be frequently seen wading in shallow water, seeking for various aquatic insects on their larvae; and a portion of a letter sent me lately by W. Rayner, Esq., of Uxbridge, who keeps a variety of birds in a large aviary near his parlour-window, for the pleasure of observing their habits, seems to prove that partiality to other prey, besides aquatic insects, has some influence on the constant visits of Wagtails to water. 'I had also during the summer and autumn of 1837 several Wagtails, the Pied and the Yellow, both of which were very expert in catching and feeding on minnows which were in a fountain in the centre of the aviary. These birds hover over the water, and, as they skim the surface, catch the minnow as it approaches the top of the water, in the most dexterous manner; and I was much surprised at the wariness and cunning of some Blackbirds and Thrushes, in watching the Wagtails catch the minnows, and immediately seizing the prize for their own dinner.' "[6]

The nest of this elegant little bird is commonly constructed of root-fibres or slender twigs, lined with hair, fine grass, and a few feathers; it is generally in the vicinity of water, at a low elevation, rarely on the ground, and in whatever situation is almost always strengthened against some firm support, as a ledge of rock, a bank, the trunk of a tree, or a wall. A hole in a wall, a crevice among loose stones, the interstices of a wood-pile or faggot-stack, the thatch of a cart-shed, or a hay-rick,—these all chosen occasionally; and Mr. Jesse has mentioned in his "Gleanings," the nest of a Wagtail built in one of the workshops of a manufactory at Taunton, amidst the incessant din of braziers who occupied the apartment. It was built near the wheel of a lathe which revolved within a foot of it, and here the bird hatched four young ones. She was perfectly familiar with the well-known faces of the workmen, and flew in and out without fear of them; but if a stranger entered, or any other persons belonging to the same factory, but not to what may be called her shop, she quitted her nest instantly, and returned not till they were gone. The male, however, had less confidence, and would not come into the room, but brought the usual supplies of food to a certain spot on the roof, whence it was brought in to the nest by his mate. Family II. Turdidæ.

(Thrushes.)

The average size of the birds of this Family is considerably superior to that of the Warblers; though the one merges into the other by insensible gradations. The beak is as long as the head, compressed at the sides; the upper mandible arched to the tip, which is not abruptly hooked; the notch is well-marked but not accompanied by a tooth; the gape furnished with bristles. The feet are long, with curved claws. The food on which the Thrushes subsist is less restricted than that of the Warblers; for besides insects and their caterpillars, snails, slugs, earthworms, &c., they feed largely on pulpy and farinaceous berries of many sorts. Many of the species are gregarious during the winter, and some through the whole year. The colours are for the most part sombre, often chaste and elegantly arranged; various shades of olive are the most prevalent hues, very frequently taking the form of spots running in chains, upon the breast and under parts. Exceptions to this subdued character of coloration are not, however, wanting in this extensive Family: thus the Orioles are distinguished for their fine contrasts of rich black and golden yellow; and the Breves (Pitta, Temm.) for their dazzling blues and greens, while some of the African Thrushes shine in the metallic lustre of burnished steel.

The Turdidæ are found in all parts of the world; the species are very numerous, and a great number are eminent as song-birds.

Genus Turdus. (Linn.)

This extensive genus, which restricted as it now is, comprises nearly a hundred and twenty species, is distinguished by having the beak slightly arched from the base to the tip, the notch distinct, and the gape set with weak and fine hairs; the wings are somewhat lengthened, the first quill so short as to be almost rudimentary, the third and fourth longest; the tail of moderate length and breadth; the feet formed for walking as well as perching on trees.

The Thrushes are, to a considerable extent, migratory in their habits, flocks frequently removing from one district of country to another, even in those climates, where the seasons are sufficiently equable to allow of their remaining without inconvenience from the weather. Thus not only do the European species resort to the more temperate parts during winter, and on the approach of summer assemble in great numbers, and return to the more northern regions, but some of the American species are continually roving about in flocks, "innumerable thousands," migrating from one region to another through the whole winter. Their food is very varied; a great portion of it is sought upon the ground, and their feet are admirably formed for walking over the places whither they chiefly resort for this purpose. In winter the various species of slugs and snails, with earthworms and grubs, that are found in open weather in moist woods and meadows, constitute their principal support; but during frosts they subsist on various berries and other wild fruits. In summer insects are abundant, and especially large caterpillars; for which they resort to the hedges, bushes, and groves. The voices of most of the species are loud and shrill; but many are admired songsters, and some, both in the Old and in the New World, are among the most eminent performers in the woodland orchestra. "The notes of some are pensive and melancholy, while others possess considerable compass of voice, accompanied with great melody. On this account they are universal favourites, and in all countries are listened to with pleasure, and with feelings which recal many recollections and associations of days which had long passed away." The flesh of the species is juicy and savoury; and as they are mostly of a size sufficient to make them worth capturing, and from their gregarious habits may often be taken in great numbers with little cost or labour, very many are killed for the table, particularly in the south of Europe, and in North America; in the latter the destruction of some of the kinds for human food is immense.

Of the seven species which, either permanently or occasionally, inhabit this country, we select for illustration the Song-Thrush or Throstle, or Mavis, (Turdus musicus, Linn.) which, though scarcely extending beyond the geographical limits of Europe, is found in every country within it, and is spread over the British Islands, during the whole year round. On the upper parts of the body, its hue is a yellowish brown, on the breast and sides, buff-orange, and on the belly, white; the whole under parts marked with triangular spots of dark brown, running in chains.

The name Song-Thrush applied to this species, as by pre-eminence, no less than its scientific appellation, indicates the prevalent opinion of its powers as a musician, in a Family where nearly all the members are musical. Its notes, usually

SONG-THRUSH.

uttered from the very summit of a tree, and day after day from the very same twig, are loud and clear, with a richness and fulness peculiar to the Thrushes. At morning and evening the woods resound with the melodious chaunt of this charming bird, frequently prolonged into the night; and if the weather be dull, the song is often continued with little intermission through the day. It has been remarked by more observers than one, that a bird's song has not only a character commons to the species, but that individual birds may often be distinguished for superior variety, power, and fulness in their notes; there being as much difference in the execution of birds of the same species, as between human voices singing the same air.

We have already mentioned the various fare on which the Thrushes regale; the species before us, while no less omnivorous, feeds with peculiar relish on shelled snails, and especially the common garden-snail, and the wood-snail (Helix hortensis, et H. nemoralis). He breaks the shell against a stone, and extracts the soft animal. Mr. Jesse, in his "Gleanings," has the following observation:— "Thrushes feed much on snails, looking for them in mossy banks. Having frequently observed some broken snail-shells near two projecting pebbles on a gravel-walk, which had a hollow between them, I endeavoured to discover the occasion of their being brought to that situation. At last, I saw a Thrush fly to the spot with a snail-shell in his mouth, which he placed between the two stones, and hammered at it with his beak till he had broken it, and was then able to feed on its contents. The bird must have discovered that he could not apply his beak with sufficient force to break the shell while it was rolling about, and he therefore found out and made use of a spot which would keep the shell in one position."[7]

The nest of the Song-Thrush is an ingenious structure, for though somewhat rough and loose externally, within it presents the appearance of a smooth, hard, cup, quite water-tight. The author of "The Architecture of Birds," thus describes its construction from personal observation:—"The interior of these nests is about the form and size of a large breakfast tea-cup, being as uniformly rounded, and, though not polished, almost as smooth. For this little cup the parent-birds lay a massive foundation of moss, chiefly the proliferous and the fern-leafed feather-moss (Hypnum prolierum et H. filicinum), or any other which is sufficiently tufted. As the structure advances, the tufts of moss are brought into a rounded wall by means of grass-stems, wheat-straw, or roots, which are twined with it and with one another up to the brim of the cup, where a thicker band of the same materials is hooped round, like the mouth of a basket. The rounded form of this frame-work is produced by the bird measuring it, at every step of the process, with its body, particularly the part extending from the thigh to the chin; and when any of the straws or other materials will not readily conform to this guage, they are carefully glued into their proper place by means of saliva, a circumstance which may be seen in many parts of the same nest, if carefully examined. When the shell, or frame, as it may be called, is completed in this manner, the bird begins the interior masonry by spreading pellets of horse or cow-dung on the basket-work of moss and straw, beginning at the bottom, which is intended to be the thickest, and proceeding gradually from the central points. This material, however, is too dry to adhere of itself with sufficient firmness to the moss, and on this account it is always laid on with the saliva of the bird as a cement; yet it must require no small patience in the little architect to lay it on so very smoothly, with no other implement besides its narrow pointed bill. It would indeed puzzle any of our best workmen to work so uniformly smooth with such a tool; but from the frame being nicely prepared, and by using only small pellets at a time, which are spread out with the upper part of the bill, the work is rendered somewhat easier.

"This wall being finished, the birds employ for the inner coating little short slips of rotten wood, chiefly that of the willow; and these are firmly glued on with the same salivary cement, while they are bruised flat at the same time, so as to correspond with the smoothness of the surface over which they are laid. This final coating, however, is seldom extended so high as the first, and neither of them is carried quite to the brim of the nest; the birds thinking it enough to bring their masonry near to the twisted band of grass, which forms the mouth. The whole wall, when finished, is not much thicker than pasteboard, and though hard, tough, and water-tight, is more warm and comfortable than at first view might appear; and admirably calculated for protecting the eggs or young from the bleak winds which prevail in the early part of the spring, when the Song-Thrush breeds."[8]

The nest of this bird is usually built in a thick bush, often an evergreen, as a holly, or in the midst of a clustering ivy; and these are selected, doubtless, because at the early season at which the Thrush builds, the deciduous trees and hedges have not yet put out their foliage, and consequently do not afford the needful concealment. There are not wanting, however, numerous instances, in which situations have been chosen, without any regard to exposure. Thus, in the "Magazine of Natural History," it is recorded

NEST OF SONG-THRUSH.

that a mill-wright engaged with three of his men in constructing a threshing-machine for a farmer living near Fife, "wrought in a cart-shed, which they had used for some time as their workshop; and one morning they observed a Mavis enter the wide door of the shed, over their heads, and fly out again after a short while. This she did two or three times, until their curiosity was excited to watch the motions of the birds more narrowly; for they began to suspect that the male and female were both implicated in this issue and entry. Upon the joists of the shed were placed along with some timber and old implements, two small harrows used for grass seeds, laid one above the other; and they were soon aware that their new companions were employed, with all the diligence of their kind, in making their nest in this singular situation. They had built it, said the workman, between one of the butts of the harrow and the adjoining tooth; and by that time, about seven o'clock, and an hour after he and his lads had commenced their work, the birds had made such progress, that they must have begun by the break of day. Of course, he did not fail to remark the future proceedings of his new friends. Their activity was incessant; and he noticed that they began to carry mortar (he said), which he and his companions well knew was for plastering the inside. Late in the same afternoon, and at six o'clock next morning, when the lads and he entered the shed, the first thing they did was to look at the Mavis's nest, which they were surprised to find occupied by one of the birds, while the other plied its unwearied toil. At last the sitting bird, or hen, as they now called her, left the nest likewise; and he ordered one of the apprentices to climb the baulks, who called out that she had laid an egg; and this she had been compelled to do some time before the nest was finished; only plastering the bottom, which could not have been done so well afterwards. When all was finished, the cock took his share in the hatching; but he did not sit so long as the hen, and he often fed her while she was upon the nest. In thirteen days the young birds were out of the shells, which the old ones always carried off"[9]

Sir William Jardine records the following anecdote as illustrating the occasional familiarity and unsuspecting confidence of this bird:—"In our own garden, last spring (1837), a somewhat singular circumstance occurred. The nest [of a Song Thrush] was placed in a common laurel bush, within easy reach of the ground, and being discovered, was many times daily visited by the younger branches of our family. It occurred to some that the poor Thrush would be hungry with a seat so constant, and a proposal was made to supply the want. A good deal of difficulty occurred, from the fear of disturbing her, but it was at last proposed that the food should be tied on the end of a stick; this was done, and the bird cautiously approached and took the first offering. The stick was gradually shortened, and in a few days the Thrush fed freely from the hand, until the young were half fledged. After this, when the parent was more frequently absent, a visit would immediately bring both male and female, who now uttered angry cries, and struck at the hand when brought near the nest."[10]

In 1833 a pair of Thrushes built their nest in a low tree at the bottom of Gray's Inn Gardens, near the gates, where passengers are going by all day long. The hen laid her complement of eggs, and was sitting on them, when a cat climbed up and killed her on the nest. The cock immediately deserted the place.

Family III. Muscicapadæ.

(Flycatchers.)

The present family seems to form the link by which the Dentirostres are connected with the Fissirostres. Like the latter, they possess a beak broad at the base, and flattened horizontally, the tip generally hooked, and the gape environed with bristles; like them, their feet are for the most part feeble, or at least not so much developed as the wings; and, like them, they feed upon winged insects, which they capture during flight. They are, however, much more sedentary in their habits; they do not pursue insects in the higher regions of the atmosphere, or wheel and course after them, as do the Swallows, but like the Todies (which have in fact often been placed in this family), they choose some prominent post of observation, where they sit and watch for vagrant insects that may pass within a short distance; on these they dart out upon the wing, but if unsuccessful at the first swoop, rarely pursue it more than a few yards; and if successful, snapping it up with the broad and bristled beak, they return to the very spot whence they sallied out, to eat it. The habit of selecting some particular twig, or the top of a post, or other spot, from which to watch and make their assaults, and to which they return after each essay, is very characteristic of these birds.

The Muscicapadæ comprise a vast number of species, scattered over every part of the globe, and differing widely in the details of generic character. They are all, however, well united together by common peculiarities of structure; and in particular, by the beak being strong, broad, flat, angular on the summit, and notched at the tip, and by the presence of strong hairs or bristles that surround its base.

Genus Muscicapa. (Linn.)

In this genus, the only British representative of the great Family to which it belongs, the beak is rather strong, triangular, sharply ridged along the upper edge, moderately dilated at the base, where it is furnished with fine but stiff hairs. The nostrils are placed near the base, are somewhat oval, and partially covered with hairs pointing forwards. The wings are rather long and pointed, the first quill very small and rudimentary, the third longest. The tail is of moderate length, either even at the extremity, or slightly forked. The feet are rather weak, the tarsus and the middle toe somewhat lengthened.

In England we have two species of this genus, of which the Spotted Flycatcher (Muscicapa grisola, Linn.) is the most common. The upper parts are dusky brown, the lower parts white, the throat, breast, and sides, spotted with narrow dashes of brown.

The Spotted Flycatcher, though sufficiently abundant throughout Great Britain, is yet only one of our migratory visitors; and its stay with us is among the very shortest. It rarely arrives before the latter end of May, when the summer is quite set in, and leaves us in September. Mr. Jesse says he has sometimes missed the species within a fortnight from the time at which the brood have quitted the nest, and expresses his

SPOTTED FLYCATCHER.

surprise that such young and tender birds should have strength sufficient to perform their migration. During this its brief sojourn, insects, and especially flies, which constitute its sustenance, are abundant; the manner in which these are taken is well described by White of Selborne, in his tenth Letter to Pennant. "There is," he observes, "one circumstance characteristic of this bird, which seems to have escaped observation, and that is, it takes its stand on the top of some stake or post, from whence it springs forth on its prey, catching a fly in the air, and hardly ever touching the ground, but returning still to the same stand for many times together." From this circumstance it is in some of the rural districts of England known as the "Post-bird." A dead branch, or the projecting twig of a tree, or the summit of a tall bush, or the angle of the roof of a house, is also not unfrequently chosen as the watch-post, the object being to secure a commanding range of observation on the surrounding air. The captured insect is never swallowed on the wing, but is held for a few seconds in the beak even after the return to the post. Insects have been supposed to be exclusively the food of this species, yet Sir William Jardine, whose accuracy of observation cannot be questioned, expressly asserts that he has occasionally seen it eat ripe cherries.

The Flycatcher is one of the least musical of British birds; its only note is a weak monotonous chirp or click; and this is uttered only while the season of incubation continues. The utterance, however, such as it is, frequently betrays the presence of the nest, which might else remain undiscovered.

The preparations for the bringing up of their family are commenced by the Flycatchers immediately on their arrival; for they have no time to lose. Various are the situations selected for the domestic economy: Sir W. Jardine mentions as a very common locality, the branches of a fruit-tree against the garden wall; a niche in the wall; capitals of pillars, or some corner amidst statuary. Mr. Martin also observes, "We have very frequently seen it between the branch of a trained fruit-tree and the wall, or in holes of the wall hidden by foliage. It will build also in the holes of aged gnarled trees, upon the ends of beams in out-houses, and in other appropriate places of concealment." From the selection of beams or rafters in tool-houses, &c., it has obtained in some parts the local appellation of "Beam-bird." But Mr. Jesse has recorded the most singular choice of a breeding locality by this bird. "I have now in my possession," he observes, "a nest of the Spotted Flycatcher, or Beam-bird, which shews the most singular habits of that bird in selecting peculiar and odd situations for building. The nest in question was found on the top of a lamp near Portland Place, London, and had five eggs in it, which had been sat upon. The top of the lamp was in the shape of a crown, and the nest was built in the hollow part of it, but perfectly concealed. In consequence of the great heat produced by the gas, the four props which supported the ornamental crown became unsoldered, and a complaint having been made to the authorities for lighting the streets, the top of the lamp, with the nest in it, was brought to them. The nest was composed of moss, hair, and fine grass. It is not a little curious that it should have been found in such a situation, and with so great a degree of heat under it. Mr. White says that in outlets about towns, where mosses, lichens, gossamer, &c., cannot be obtained, birds do not make nests so peculiar each to its species, as they do in the country. Thus the nest of the town Chaffinch has not that elegant appearance, nor is it so beautifully studded with lichens as those in the rural districts; and the Wren is obliged to construct its nest with straws and dry grasses, which do not give it that roundness and compactness so remarkable in the usual edifices of that little architect. The nest in question was not lined with feathers and spiders' webs, as is generally the case.

"I have myself discovered the Flycatcher's nest in very odd situations;—one behind a decayed piece of bark attached to an elm tree in Hampton-court Park, and another concealed amongst the ornaments of the beautiful iron gates of Hampton-court Gardens. In Mr. White's unpublished notes, he mentions a Flycatcher having built its nest in a very peculiar manner on a shelf fixed to the wall of an out-house, and behind the head of an old rake lying on the shelf. Indeed the bird would appear to have a partiality for the last mentioned implement, for in Loudon's 'Magazine of Natural History,' it is stated that a Flycatcher's nest was built upon a wooden rake lying on the ground in a cottage garden at Barnsford, near Worcester. In this nest the female laid eggs, and even sat on them, indifferent to any one passing in the garden." [11]

"A curious circumstance," observes Mr. Yarrell, "in reference to this bird, has been noticed by Thomas Andrew Knight, Esq., the President of the Horticultural Society. A Flycatcher built in his stove several successive years. He observed that the bird quitted its eggs whenever the thermometer in the house was above 72°, and resumed her place upon the nest again, when the thermometer sunk below."[12]

The eggs are four or five in number, of a greyish-white hue, marked with pale orange-brown spots.

Family IV. Ampelidæ.

(Chatterers.)

The beak in this Family is more stout in proportion to its length than in the preceding, approaching, especially in the form of the lower mandible, to that of the Conirostres; the upper mandible is, however, somewhat broad at the base, flat, with the superior edge more or less angular and ridged, and the tip distinctly notched. The feet are usually stout, with the outer toe united to the middle one, as far as, or beyond the first joint.

The species composing this Family, though not very numerous, are of various forms, and are widely scattered over the globe. Many of them are distinguished for the soft and silky character of their plumage, and for the brilliant colours with which it is adorned; and not a few for unusual appendages, either to some of the feathers, or to the skin of the body. They feed principally on berries, and other soft fruits; occasionally also on insects. Genus Ampelis. (Linn.)

Until recently, the genus before us was known only by two species, one of which is spread over Europe, the northern parts of Asia as far as Japan, and the western portion of North America, as far as the Rocky Mountains; and the other inhabits the Atlantic side of the last-named continent, extending from Canada to Mexico. A third species has, however, of late years, been discovered, of much more limited range, being confined to the remote islands of Japan.

The distinctive characters of this genus may be thus summed up; the beak short, strong, elevated, broad at the base, the upper mandible curved towards its extremity, with a strongly marked notch; the gape very wide; the nostrils oval, covered at the base with feathers, or strong hairs, directed forwards; the wings moderately long, with the first, or the first and second quills longest; the tail short and nearly even; the feet rather short, plumed slightly below the heel, the outmost and middle toes connected. The plumage of the head forms a long and pointed crest, capable of being erected, which is common to both sexes. Two of the species, at least, are distinguished by having singular appendages to the secondaries of the wing, and sometimes to the feathers of the tail; the shaft of the feather being prolonged beyond the vane, and its tip dilated into a flat oval appendage, of a brilliant scarlet hue, and exactly resembling in appearance red sealing-wax. Hence these birds are frequently known by the name of Wax-wings, as from the silky softness and smoothness of the plumage generally, and particularly of that of the tail, they are sometimes called Silk-tails.

FEATHER OF CHATTERER.

We have alluded to the very wide geographical range of the only species known in Europe, which, from its greater frequency and abundance in the south-east of Germany, is commonly known as the Bohemian Chatterer, or Silk-tail (Ampelis garrulus, Linn.). Its occurrence, however, in most of the countries where it has been recognized, is desultory, irregular, and not determined by any known laws. At uncertain intervals they appear in particular districts in immense flocks, and so remarkable have such visitations appeared, that they have been carefully recorded as events of history, and supposed to be in some way ominous of great public calamities. Thus in 1530, 1551, and 1571, vast numbers appeared in northern Italy, and in 1552, along the Rhine, near Mentz, they flew in clouds so dense, as to darken the sun. Of late years, however, in Italy, and Germany, and especially in France, they have been rarely observed, and then only in small flocks that seemed to have strayed from the great body. In 1807 and 1814, they were numerous in western Europe.

In the British islands the Bohemian Chatterer can be considered only as a rare and straggling visitant, though many instances of its occurrence, and that in some numbers, are on record, more particularly in the north, and during winters of extraordinary severity. In the winter of 1787, many flocks were seen all over the county of York; in that of 1810 large flocks were dispersed over the kingdom, and in the great storm in the winter

BOHEMIAN CHATTERER.

of 1823, several were again observed. In the extreme north of Norway and Sweden, and the icy forests of Russia, they are met with in great numbers every winter, appearing much earlier than in more temperate countries; yet even here they are only migratory visitors, receding from regions still more inhospitable, which we may conjecture to be those cold and arid plains of great elevation, which occupy the central portion of Asia, or the bleak and barren wilds of northern Siberia.

The Silk-tail is somewhat less than a Thrush; its general plumage is of a vinous or purplish-red hue; the throat is deep black, as is a band on each side of the head; the crown and crest are chestnut brown; the tail and wings are black with yellow tips; the coverts have white tips; some five or six of the secondaries, and, in very old males, some of the tail-feathers also, have the dilated, scarlet appendages to the shafts already alluded to.

The Prince of Canino thus speaks of the habits of this pretty bird. "Besides their social disposition, and general love of their species, these birds appear susceptible of individual attachment, as if they felt a particular sentiment of benevolence, even independent of reciprocal sexual attraction. Not only do the male and female caress and feed each other, but the same proofs of mutual kindness have been observed between individuals of the same sex. This amiable disposition, so agreeable for others, often becomes a serious disadvantage to its possessor. It always supposes more sensibility than energy, more confidence than penetration, more simplicity than prudence, and precipitates these as well as nobler victims, into the snares prepared for them by more artful and selfish beings. Hence they are stigmatized as stupid; and as they keep generally close together, many are easily killed at once by a single discharge of a gun. They always alight on trees, hopping awkwardly on the ground. Their flight is very rapid; when taking wing they utter a note resembling the syllables zi, zi, ri, but are generally silent, notwithstanding the name that has been given them. They are, however, said to have a sweet and agreeable song in the time of breeding, though at others it is a mere whistle."[13]

The zoologist just cited speaks of the food of these birds in America, as consisting of different kinds of juicy berries, and in summer principally of insects. They are fond of the berries of the mountain ash, and poke-weed (Phytolacca), are extremely greedy of grapes, and also, though in a less degree, of juniper and laurel berries, apples, currants, figs, and other fruits. In Britain, Sir William Jardine and other naturalists, mention the various kinds of winter berries, and those of the holly in particular. And Bechstein, noticing its habits in Germany, says, "When wild we see it in the spring eating, like Thrushes, all sorts of flies and other insects; in autumn and winter, different kinds of berries; and in time of need, the buds and sprouts of the beech, maple, and various fruit-trees. Indeed, from his account of its manners in captivity, its appetite would seem to be almost omnivorous. His opinion of its character is somewhat less favourable than Prince Bonaparte's. In fact, he draws so unpleasing a picture of its greediness and dirty habits, in his work on Cage-birds, that, if correct, few would desire its captivity. The following is a portion of his observations, omitting what is more repulsive. "During the ten or twelve years that it can exist in confinement, and on very meagre food, it does nothing but eat, and repose for digestion. If hunger induces it to move, its step is awkward, and its jumps so clumsy as to be disagreeable to the eye. Its song consists only of weak and uncertain whistling, a little resembling that of the Thrush, but not so loud. While singing it moves the crest, but hardly moves the throat. If this warbling is somewhat unmusical, it has the merit of continuing throughout every season of the year. When angry, which happens sometimes near the common feeding-trough, it knocks very violently with its beak. It is readily tamed." The same writer remarks that the two kinds of univeral paste appear delicacies to it; and that it is satisfied even with bran steeped in water. It swallows every thing voraciously, and refuses nothing eatable, such as potatoes, cabbage, salad, fruit of all kinds, and especially white bread.

The Chatterer is easily taken by means of nooses, to which mellow berries are attached. It is not deterred from rushing into nets and springes, even by the sight of its companions entrapped and hanging in the nooses, uttering cries of distress. The flesh is esteemed as delicate and well-flavoured.

Nothing whatever is known of the domestic economy of these birds, either in the Old or the New World. They certainly have never been known to breed in any part of Europe, where indeed they are seen only in winter. Central Asia is supposed to be the scene of their summer residence, and the bringing up of their family. The kindred species of the United States (A. Carolinensis, Briss.), however, builds a large nest in the fork of a cedar or apple tree; composed of stalks of grass, coarse without, and fine within. Here it lays three or four eggs, of a bluish white, marked with dots of black and purple.

Family V. Laniadæ

(Shrikes.)

Among the most interesting phenomena of Zoology are those very numerous cases, in which some strongly marked peculiarities of structure or habit in one group are reproduced in another, widely removed from it in the totality of its organization. An instance of this analogy is now before us. The Shrikes are undoubtedly Passerine birds in their whole structure, yet no one can look upon the beak of one of these birds without being strongly reminded of that of the Falconidæ, in its strength, its arched form, its strongly hooked point, and in the distinct tooth which precedes the usual notch of the Dentinstrostral type. And this structure of the beak is accompanied by a carnivorous appetite, a rapacious cruelty, and a courage that are truly Accipitrine, and have induced their association with the birds of prey, both by unscientific and scientific observers. The Shrikes not only devour the larger and more powerful insects, but also pursue, attack, and overcome small birds and quadrupeds, seize them in their beak or claws, and bearing them to some station near, tear them to pieces with their toothed and crooked beak. Mr. Martin mentions having seen a species from New Holland (Vanga destructor, Temm.), after strangling a mouse, or crushing its skull, double it through the wires of its cage, and with every demonstration of savage triumph proceed to tear it limb from limb, and devour it.[14] Mr. Swainson, alluding to the rapacity and power of the Laniadæ, remarks that the comparisons frequently drawn between them and the Falconidæ, are no less true in fact, than beautiful in analogy; for that many of the latter sit on a tree for hours, watching for such little birds as may come within reach of a sudden swoop, when pouncing on the quarry, they seize it in their talons, bear it to their roost, and devour it piecemeal. These, he adds, are precisely the manners of the true Shrike; yet, with all this, the structure of the Falcons and Shrikes, and their more intimate relations are so different, that these birds cannot be classed in the same Order, though they illustrate that system of symbolic relationship termed analogy, which Mr. Swainson believes to pervade creation; yet the two groups are in no wise connected, and there is, in consequence, no affinity between them.

In addition to what we have said of the characters which the beak presents in this Family, we may add that the claws, as instruments of capture, are peculiarly fine and sharp in the typical species, and this character pervades, more or less, the whole Family. In general, also, the tail-coverts have a tendency to be puffed out into a soft and loose protuberance on the lower part of the back; in some, however, the shafts of these feathers are stiff and prolonged.

Representatives of the Family are scattered all over the world.

Genus Lanius. (Linn.)

The true Shrikes,—which are common to the three continents of the eastern hemisphere, and to North America, but are wanting in the southern division of that continent, as well as in Australia,—are distinguished by the following characters. The beak is rather short, and compressed at the sides, and not depressed as in the Flycatchers; the upper mandible hooked, and furnished with a strong and prominent tooth: the wings have the first three quills graduated, the third and fourth being the longest: the claws sharp, and moderately hooked: the tail usually lengthened, They are birds of much elegance of form, and the hues of the plumage are chaste and pleasing, consisting of various shades of blue-grey, rufous, and white, set off with fine contrasts of black on the head, wings, and tail.

Three species of this genus are known in England, but all as migratory visitors; of these we select as an example, the Great Grey Shrike (Lanius excubitor, Linn.), the largest, though not the most common. It is about as large as the Blackbird, but of superior elegance, from the graduated form of its long tail, as well as from the beautiful distribution of its pleasing colours. The whole upper parts are of a clear and pearly grey; the under parts pure white; the wings and tail black, tipped with white; on the former there is also a large patch of white at the base of the primaries; a band of black passes along each cheek, inclosing the eye.

The Grey Shrike cannot be considered as a regular migratory visitor to these islands, though

GREY SHRIKE.

it has occurred with considerable frequency in most parts, at least of England. Mr. Yarrell observes that it has been obtained in Surrey, Sussex, Wiltshire, Dorsetshire, Devonshire, Worcestershire, and Cheshire; and in one or two instances, in the north of Ireland. North of London it has been killed in Hertfordshire, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, Yorkshire, Cumberland, Northumberland, and Durham. Sir W. Jardine speaks of it as a rare bird in Scotland, a few instances only of its capture in the south of that kingdom having come to his knowledge. It is spread over the continent, however, from Lapland to Spain and Italy. Its appearance with us, as in the south of Europe, is in the winter months; once or twice only it has been observed in England in summer, probably through some accidental circumstance; and there is no reason to believe it ever breeds with us. Mr. Rennie, in the "Architecture of Birds," speaks of its nest as common in Kent, but this is probably a mistake. Its winter residence with us is not so infrequent a thing, but that the bird has obtained a recognition among the common people, and numerous local names attest their familiarity with it. Thus it is known by the appellations of Butcher-bird, Mattagass, Mountain Magpie, Murdering Pie, Shreek, and Shrike; and by the ancient British it was named Cigydd Mawr.

We have alluded to the interesting analogy between the Shrikes and the Falcons; nor is this so recondite as to have been remarked only by the observant man of science. In the days of falconry the species before us was actually supposed to be a degenerate sort of hawk, as appears from the curious notices of it in the books of that age. In "The Booke of Falconrie or Hawkinge" (London, 1611), we find "the Sparowhawke," immediately succeeded by "the Matagesse;" and at the end of "A generall division of Hawkes and Birdes of Prey, after the opinion of one Francesco Sforzino Vycentino, an Italian gentleman-falconer," there is the following account "Of the Matagasse:"—

"Though the Matagasse bee a Hawke of none Account or Price, neyther with us in any Use; yet neverthelesse, for that in my Division I made Recitall of her Name, according to the French Author, from whence I collected sundries of these Points and Documents appertaining to Falconrie, I think it not beside my purpose briefly to describe herre unto you, though I must needs confesse, that where the Hawke is of so slender Value, the Definition, or rather Description of her Nature and Name, must be thought of no great Regard."

After the description the author goes on to say,—"Her feeding is upon Rattes, Squirrells, and Lisards, and sometime upon certaine Birdes she doth use to prey, whome she doth intrappe and deceive by flight, for this is her Devise. She will stand at pearch upon some Tree or Poste, and there make an exceedyng lamentable Crye and Exclamation, such as Birdes are wonte to doe being wronged, or in Hazard of Mischiefe, and all to make other Fowles believe and think that she is very much distressed, and standes needefull of Ayde, whereupon the credulous sellie Birdes do flocke together presently at her Call and Voice, at which Time, if any happen to approache near her, she out of Hand ceazeth on them, and devoureth them (ungratefull, subtill Fowle!) in Requitall of their Simplicity and Paines. These Hawkes are in no Accompt with us, but poore simple Fellowes and Peasantes sometimes doe make them to the Fiste, and being reclaymed after their unskillfull Manner, do beare them hooded, as Falconers doe their other Kind of Hawkes whome they make to greater Purposes. Heere I ende of this Hawke, because I neyther accompt her worthe the name of a Hawke, in whom there resteth no Valour or Hardiness, ne yet deserving to have any more written of her Propertie and Nature, more than that she was in mine Author specified as a Member of my Division, and there reputed in the Number of long-winged Hawkes. For truely it is not the Propertie of any other Hawke, by such Devise and cowardly Will to come by their Prey, but they love to winne it by main Force of Winges at random, as the round-winged Hawkes doe, or by free stooping, as the Hawkes of the Tower doe most commonly use, as the Falcon, Gerfalcon, Sacre, Merlyn, and such like, which doe lie upon their wing, roving in the Ayre, and ruffe the Fowle, or kill it at the encounter."

Notwithstanding the slighting tone in which this author treats the attempts of the "poore fellowes" to reclaim this bird, Willughby affirms that it received a more refined and scientific consideration. "Although," says he, "it doth most commonly feed upon insects, yet doth it often set upon and kill not only small birds, as finches, wrens, &c., but (which Turner affirms himself to have seen) even Thrushes themselves: whence it is wont by our falconers to be reclaimed and made for to fly small birds."

But upon the Continent the Shrike appears to have rendered a more important service to the falconer, than the capture of small birds, even the capture of the higher kinds of Falcons themselves. Sir John Sebright informs us that the Peregrine Falcon is taken by placing in a favourable situation a small bow-net, so arranged as to be drawn over quickly by a long string that is attached to it. A pigeon of a light colour is tied on the ground as a bait, and the falconer is concealed, at a convenient distance, in a hut made of turf, to which the string reaches. The Lanius excubitor, that is, the Warder Butcher-bird,[15] from the lookout that he keeps for the Falcon, is tied on the ground near the hut; and two pieces of turf are so set up as to serve him, as well for a place of shelter from the weather, as of retreat from the Falcon. The falconer employs himself in some sedentary occupation, relying upon the vigilance of the Butcher-bird to warn him of the approach of a Hawk. This he never fails to do, by screaming loudly when he perceives his enemy at a distance, and by running under the turf when the Hawk draws near. The falconer is thus prepared to pull the net, the moment that the Falcon has pounced upon the pigeon.[16]

The Grey Shrike delights more in parks and cultivated fields, where hedge-rows and clumps of trees abound, than in deep forests, or a very open country. The small birds and quadrupeds, or large insects on which it feeds, are taken by open violence, deprived of life, and then impaled upon some thorn or sharp twig, to be more readily devoured. This habit of hanging up his meat, butcher-like, has given him both scientific and vulgar appellations. Mr. Selby says : " I had the gratification of witnessing this operation of the Shrike upon a Hedge-sparrow (Accentor modularis) which it had just killed, and the skin of which, still attached to the thorn, is now in my possession. In this instance, after killing the bird, it hovered with the prey in its bill, a short time, over the hedge, apparently occupied in selecting a thorn fit for its purpose. Upon disturbing it, and advancing to the spot, I found the Accentor firmly fixed by the tendons of the wing to the selected twig."[17] We are informed by Le Vaillant that the same habit marks this bird in the wilds of South Africa ; and he observed that the spine or thorn was invariably thrust through the head of the prey, whether insect or bird, which was not devoured at the time of impalement, but allowed to hang until the calls of hunger induced the Shrike to return to its stored provision. And the allied species in North America (L. borealis, Vieill.) resorts to the very same practice, as recorded by Heckewelder, Wilson, and others.

The same singular habits are retained in captivity. Mr. Yarrell has extracted part of a letter from Mr. Doubleday, of Epping, a well-known naturalist, to the effect that an old Grey Shrike had been in his possession twelve months, having been captured near Norwich, in October, 1835. It had become very tame, and would readily take its food from its master's hands. When a bird was given it, it invariably broke the skull, and generally ate the head first. It sometimes held the bird in its claws, and pulled it to pieces in the manner of the Hawks; but seemed to prefer forcing part of it through the wires, then pulling at it. It always hung what it could not eat up on the sides of the cage. It would often eat three small birds in a day. In the spring it was very noisy, one of its notes a little resembling the cry of the Kestrel.[18] Bechstein, also, who has added to our knowledge so many particulars of the manners of birds in captivity, states of this species, that if it be captured when it is old, mice, birds, or living insects may be thrown to it, taking care to leave it quite alone, for as long as any one is present it will touch nothing; but soon becomes more familiar, and will eat meat, and even the universal paste. An ounce of meat at least is eaten at a meal, and there should be a forked branch or crossed sticks in the cage, across the angles of which it throws the mouse or any other prey, and then darting on it behind from the opposite side of the cage, devours every morsel. Repeated instances have occurred of its voracity inducing it to dart upon small birds hung up in cages.

The imitative power attributed to the Shrike may be not altogether a fiction: different authors ascribe very different notes to it; one resembling the cry of the Kestrel is noted above; Bechstein speaks of its warbling much like the Grey Parrot, the melody interrupted, however, by harsh discordant notes; and a writer in the "Naturalist" compares some strains which he heard it utter to the notes of the Stonechat. But while listening to these, to his surprise, they were discarded, and others adopted of a softer and more melodious character, never, however, prolonged to anything like a continuous song.

According to Mr. Hewitson, the Shrike builds its nest in thick bushes and high hedges; it is composed of umbelliferous plants, roots, moss, and wool, lined with finer roots and dried grasses. The eggs are from five to seven in number, of a bluish white, spotted and blotched with brown or purplish grey.[19]

- ↑ Classif. of Brids

- ↑ Yarell's Brit. Birds, i. 303.

- ↑ The Nightingale.

- ↑ Spec. de la Nature, i. 156.

- ↑ Syme's Brit. Song-birds, p. 97.

- ↑ Yarrell's Brit. Birds, i. 398.

- ↑ "Jesse's "Gleanings," p. 36.

- ↑ Arch, of Birds, p. 125.

- ↑ Mag. of Nat. Hist. iii. 238.

- ↑ Nat. Lib. Ornithology, ii. 93.

- ↑ Jesse's "Gleanings," p. 247.

- ↑ Brit. Birds, i. 174.

- ↑ Amer. Ornithology, iv. 76. (Constable's ed.)

- ↑ Pict. Mus. i. 303.

- ↑ Lanius (Lat.), a butcher; excubitor, a watchman,

- ↑ Observations upon Hawking.

- ↑ Br.Ornith. i 149.

- ↑ Brit. Birds, i. 158.

- ↑ Hewitson's Oology, cviii.