Natural History, Birds/Scansores

ORDER III. SCANSORES.

(Climbing Birds.)

The association of the Families usually arranged in one group, under the above title, or that of Zygodactyli or yoke-footed birds, is by most naturalists felt to be unsatisfactory. Unlike in food, in form, in habits, and economy, the single character which they have in common, is that their four toes are arranged in two pairs, the outer toe being turned backward more or less permanently, like the thumb, so that these are opposible to the middle and inner toes, which point in the opposite direction. From this structure results a more efficient power of grasping, or of clinging to perpendicular or reversed surfaces, associated with climbing habits in the principal Families, as those of the Parrots and the Woodpeckers.

In the other Families, however, those of the Toucans and the Cuckoos, this disposition of the toes is not accompanied with the power of climbing, properly so called; though the latter, and perhaps the former, do certainly move about the branches of trees, in a manner diverse from that employed by the true perching or Passerine birds. At the same time it must be borne in mind that the faculty of climbing, even if common to the whole of this Order, is by no means peculiar to it; as the Creepers and Nuthatches, whose toes are arranged on the Passerine type, can climb and even run on perpendicular and inverted surfaces with much more facility than any of the so called Scansorial birds.

FOOT OF PARROT AND OF WOODPECKER.

As so little can be predicated of these birds in common, with the exception of the structural peculiarity above-noted, we defer the summary of habits and economy, until we define the respective Families which are included in the order. These are four in number, Rhamphastidæ, Psittacidæ, Picidæ, and Cuculidæ. Of these, the first is confined to the southern portion of the New World; the others are spread widely over both hemispheres.

Family I. Rhamphastidæ.

(Toucans.)

The great development of the beak in the Family with which we dismissed the Passerine Order, prepared us for its size and somewhat similar structure in the Toucans. They too are large birds, which have the beak of great size, this organ in the typical genus being nearly as large and as long as the body itself: internally it is very cellular, being permeated by a very thin and fragile network of bony fibres; hence it is exceedingly light, and is borne with so much ease and grace as entirely to remove the idea of uncouthness which those are apt to attach to it who have seen it only in figures or in stuffed specimens. The mandibles are both curved downwards to the tip, which is somewhat acute, the ridge is commonly rounded, the edges of both mandibles are regularly notched at wide intervals. The tongue is long, slender, and barbed on each side, so as to resemble a narrow feather, the beards directed forwards. The wings are short and rounded; the tail long and broad. The feet, though yoke-toed, seem to be rather adapted for grasping than climbing, and much resemble those of the Cuckoos.

The Rhamphastidæ are confined to the tropical parts of continental America, where they reside in the depth of the magnificent forests, associating in small flocks, which are said frequently to include several distinct species. They feed on the eggs and nestlings of small birds, on fruits, and also on insects. Their motions are light and elegant to an extreme degree, leaping from bough to bough with the most graceful agility; their flight, however, is laboured, and in straight lines; and though rapid, is evidently attended with much exertion; they fly with difficulty against the wind, raising the beak above the axis of the body, and propelling themselves at short intervals. They nestle in hollow trees, excavating the decaying wood with their beaks, and lay in the cavity two eggs, of a round form, and delicately white in hue.

Genus Rhamphastos. (Linn.)

The Toucans proper have the beak ungrooved, thicker than the head; the nostrils entirely concealed, and placed at the edge of the thickened frontlet of the beak. The wings are short; the four outmost quills graduated, and abruptly pointed. The tail is comparatively short; squared or but slightly rounded at the extremity. In their internal anatomy they are remarkable for the clavicles being separate, instead of uniting to form the furcula, or merrythought. They are birds of large size, generally black on the upper parts, with vivid colours, chiefly red and yellow, on the throat and breast. The beak is often tinted with brilliant hues, which vanish after death.

We know but little of the habits of the Toucans in their native forests, but in captivity the manners of two species have been detailed in interesting memoirs by Mr. Broderip and Mr. Vigors. The former of these gentlemen was informed by Mr. Swainson who had seen these birds in the forests of Brazil, that he had frequently observed them perched on the tops of lofty trees, where they remained as if watching. This circumstance, combined with others connected with the remains of food found in the stomachs of such as he dissected, had induced him to suspect that the Toucans were partly carnivorous, feeding on the eggs and young of other birds, as well as fruits and berries; and that while perched upon these high trees, they were in fact busily employed in watching the departure of the parent birds from their nests. Mr. Swainson, however, had never detected a Toucan in the fact, nor were his dissections quite conclusive as to the animal nature of their food. Dr. Such also informed Mr. Broderip that he had seen these birds in Brazil, frequently engaged in quarrels with the monkeys, and that he was certain that they fed on eggs and nestlings, as well as on a certain fruit called the toucan-berry.

These presumptions were abundantly confirmed by the carnivorous appetite of the specimen seen by Mr. Broderip in a state of captivity. The bird had been fed exclusively on vegetable food; but one day, a Canary having escaped from its cage, and approached that of the Toucan, the latter was extremely excited, and on the barrier being removed it instantly seized the Canary and devoured it. On hearing of this incident, Mr. Broderip went to see the Toucan, and requested the keeper to bring in a small bird, in order to observe the result. On a Goldfinch being introduced into the cage, it was eagerly seized, and killed in a moment by the pressure of the powerful beak. Then holding it on the perch with one foot, the Toucan proceeded to strip off the feathers; after which he broke the bones of the limbs by a strong lateral wrench with his beak, and, tearing it to pieces, devoured it portion by portion, with the highest manifestations of enjoyment. Ever and anon he would take the prey in his beak, and hop with it from perch to perch, making a hollow clattering noise, and shivering his wings. The beak and feet of his prey gave him the most trouble, but he devoured the whole, and evidently with great relish; " for whenever he raised his prey from the perch, he appeared to exult, now masticating the morsel with his toothed bill, and applying his tongue to it, now attempting to gorge it, and now making the peculiar clattering noise, accompanied by the shivering motion above mentioned." After this, animal food was mixed with the diet of this bird, in the form of meat, varied with a living bird occasionally; and it was observed that he greatly preferred the animal to the vegetable diet, carefully picking out all the morsels of the former before he would eat the latter.

There is a peculiarity connected with the repose of the Toucans which is worth noticing, as it was observed in the species seen by Mr. Broderip, and in that in the possession of Mr. Vigors. The latter gentleman observes of his specimen, that its habits were singularly regular. As the dusk of evening approached, it finished its last meal for the day, took a few turns, as if for exercise, around the perches of its cage, and then settled on the highest, disposing itself at the moment of alighting in its singular posture of preparatory repose, its head drawn in between the shoulders, and the tail turned up vertically over its back. In this posture he generally remained about two hours, in a state between sleeping and waking, his eyes for the most part closed, but opening on the slightest interruption. At such times he would allow himself to be handled, and would even take any favourite food that was offered him, without altering his position further than by a gentle turn of the head. He would also suffer his tail to be replaced by the hand in its natural downward posture, and would then immediately return it again to its vertical position. In these movements the tail seemed to turn as if on a hinge that was operated on by a spring. At the end of about two hours he began gradually to turn his bill over his right shoulder, and to nestle it among the feathers of his back, sometimes concealing it completely within the plumage, at other times leaving a slight portion of its upper edge exposed. At the same time he drooped the feathers of his wings and those of the thigh-coverts, so as to encompass the legs and feet, and thus nearly assuming the appearance of an oval ball of feathers, he secured himself against all exposure to cold.[1]

The writer of this work had for some little time in his possession a specimen of the Keel-beaked Toucan (Rhamphastos carinatus, Swains.), which he brought to England from Jamaica. The species is not, however, a native of the West Indian islands, but of the northern extremity of South America, whence this specimen was originally procured, and the southern provinces of Mexico. We do not recollect having ever observed the upturning of the tail during repose, spoken of in the two species above-noticed. It was in the highest health and spirits; and its movements were lively and graceful, leaping from side to side of its cage, or from perch to perch, with untiring agility. It had

KEEL-BEAKED TOUCAN.

The Keel-beaked Toucan is conspicuous for the number and brilliancy of the hues that adorn its beak, which is of large size. It is remarkable also for the thin ridge or keel which runs along the upper edge of this organ; this ridge, as well as the edges of the upper mandible, is of a golden yellow; the sides are rich green; and the lower mandible is blue changing into green; the tips of both mandibles are scarlet; a narrow band of black surrounds the base of the beak. The naked skin which environs the eyes is violet, as are also the feet. The plumage of the throat and breast is lemon-yellow, margined by a crescent-band of scarlet at the lower part. The upper tail-coverts, are white, and those beneath are scarlet. All the rest of the plumage is of a shining black.

This beautiful species was considered, when Mr. Gould published his magnificent monograph of the Rhamphastidæ, as very rare; though it was seen alive by Edwards in the last century. Within a few years, however, several living individuals of this species have been brought to this country, most of which are in the noble menagerie of the Earl of Derby at Knowsley.

Family II. Psittacidæ.

(Parrots.)

In their general form, the structure of their beak, the cere that encloses its base, their thick and fleshy tongue, the arrangement and form of their toes, the scales with which their feet are clothed, many details of their internal anatomy, combined with their remarkable habits, and their great intelligence and docility,—the Parrots differ very widely from the Families with which they are usually associated, and form a group compact and well-defined among themselves, but isolated in a remarkable degree from all others. Many Naturalists of eminence, indeed, do not hesitate to assign to the Parrots the rank of an Order, commencing the series with them, thus making them precede the Birds of Prey, as the Quadrumana, which they are supposed to represent, are put before the Carnivora. "If we except," says Mr. Blyth, "the trivial character of their outer toe being reversed,—and their foot, even, is in all other respects extremely different,[2] and covered with small tubercle-like scales, instead of plates as in all the Passerinæ, and the rest of the yoke-footed genera without exception,—they have absolutely nothing in common with the other Zygodactyli [or Scansores] that should entitle them to range in the same special division: their whole structure is widely at variance, and if there be one group more than another to which they manifest any particular affinity, it is that of the Diurnal Birds of Prey, which, we conceive, should range next to them, though still very distantly allied. They certainly accord with the Falcons more than with any other bird in the contour of the beak, and the nostrils are analogously pierced in a membrane termed the cere: they have a similar enlargement of the œsophagus [or gullet], which occurs in no other zygodactyle bird, but which is glandular as in the Pigeons, secreting a lacteal substance with which the young are at first nourished; the Parrots and Pigeons being almost the only birds which subsist exclusively on vegetable diet at all ages."[3]

On the other hand, most naturalists, in their systematic arrangements, and even many of those who argue for a different position and rank, agree to retain these birds in the situation and relationship in which they were placed by Linnaeus, viz., in immediate proximity to the Toucans and Woodpeckers. And, in defence of this arrangement, we will refer to the interesting observations of Mr. Vigors, whose perceptions of the affinities of birds have perhaps never been surpassed. That ornithologist, while he places the Parrots next to the Toucans, and concurs in the general views which bring these birds into neighbouring groups,—acknowledges that he is unacquainted with any forms which soften down the important difference between the bills and tongues of the one and the other of these Families; and declares his opinion that the Psittacidæ afford more difficulties to the inquirer than any other known group in the whole Class.

HEAD OF MACAW

Between the Parrots and the Woodpeckers there seemed to Mr. Vigors, at first, to be an equal diversity, arising from the structure of the beak and tongue, but he was decided in his opinion of their proximity, by observing that while there is no other group with which the former accord more closely in such characters, they possess an affinity to no birds but the Picidæ, in the structure of the foot and the use to which they apply it. Of the birds commonly considered as Climbers, possessing yoked toes, he remarks that the Parrots and the Woodpeckers are the only families whose toes are strictly and constantly disposed in pairs; the external toe of the other Scansores being retractile; and these latter are never seen to climb, at least to that extent which is common to the two families in question. "We may thus venture," he continues, "to separate the Parrots and Woodpeckers from the other Families, and to associate them together, in consequence of the affinity in these essential characteristics of the tribe. In this point of view they will compose its normal groups as Climbers par excellence; differing, however, as to the mode in which they climb; the Parrots using the foot chiefly in grasping the object, which assists them in their ascent, and in conjunction with the bill, while the Picidæ rely upon the strength and straightness of the hind toes, in supporting them in a perpendicular position on the sides of trees; in which posture they are also assisted by the strong shafts of the tail feathers. While I was influenced by these general points of coincidence in placing the Psittacidæ and Picidæ together, I recognised a group which appeared to intervene between them, and to diminish the apparent distance that exists even in the form of their bill. That important group which comprises the Linnaean Barbets, evidently exhibited the expected gradation in the structure of that member; the bill of Pogonias, Illig., approaching most nearly that of the Parrots, by its short, strong, and hooked conformation, while the straighter and more lengthened bill of the true Bucco united itself to that of Picus. Many other particulars in form, and also in extraordinary conformity in colouring, still further pointed out the affinity; and I was at length confirmed in my conjectures respecting the situation of these birds, by arriving at a knowledge of their habits being actually those of the true Woodpeckers, and of their chief affinity being to that group. The regular gradation by which these two families, united in their general characters, and those the characters, it must be remembered, most prominent and typical in their own tribe, are also united in their minuter points of formation, appears to me now eminently conspicuous."

Respecting the minuter points alluded to, Mr. Vigors remarks that some of the Psittaridæ, among which he particularises the Ring-necked Parroquets of India (Palæornis), partially employ the tail in supporting themselves as they climb, in a manner corresponding to that of the Woodpeckers. The tongue, also, peculiar to the Parrots, as he observes, becomes slenderer, and as is said, more extensible in that group of which Psittacus aterrimus, Gmel., is the representative; thus evincing an approximation, slight indeed, but still an approximation, to that of the Woodpeckers.[4]

The technical characters by which the Psittacidæ are distinguished may be briefly summed up as follows: The beak is very short, the upper mandible greatly curved downward at the tip, and overhanging the lower, which is much shorter, and, as it were, abruptly cut off at the extremity: the upper mandible is moveable: its base is enveloped in a cere, in which the nostrils are pierced. The tongue is thick, fleshy, and undivided. The feet are short and broad, and covered with numerous small rounded scales.

The power of moving the upper mandible, which is wanting to the Mammalia, is common, and almost universal, among Birds. In the present Family, however, it is much more highly developed than in other birds; the mandible not being

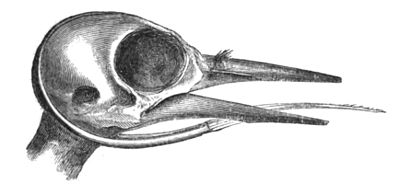

SKULL OF MACAW

connected into one piece with the skull, by elastic and yielding bony plates, as is the case with birds in general, but constituting a particular bone, distinct from the rest of the skull, and jointed to it. This mobility is rendered more conspicuous by the circumstance of their vigorous jaws being set in motion by a greater number of muscles than are found in other birds. The advantages of this peculiarity of structure are obvious, when we remember the use which a Parrot makes of this organ, as a third hand, to assist it in climbing from bough to bough, or about the bars of its cage when in confinement.

The soft and thick tongue so characteristic of the Parrots, is doubtless a highly sensitive organ of taste. It is covered, like that of the Mammalia, with papillæ, and being moistened by a constant secretion of saliva, they are able to select and taste different kinds of food. In some of the Australian species, which suck the nectar of flowers, the tongue, while retaining the thick form and fleshy structure common to the Family, is distinguished by the peculiarity of terminating in a number of very delicate and close-set filaments, which can be protruded and expanded like a brush. Mr. Caley records that one of these species (Trichoglossus hæmatodus, Vig.) in confinement, on being shewn a coloured drawing of a flower, applied the tip of its tongue to it, as if it would suck it; and on another occasion made a similar attempt on seeing a piece of printed cotton furniture.

The Parrots are adorned with the richest and most brilliant hues, of which a soft and lustrous green may be considered as the most prevalent, varied, however, with scarlet, yellow, and blue, in profusion, usually arranged in broad and well-defined masses. Though susceptible of increased lustre from the play of light, particularly in such as are of green hues, the plumage of the Parrots does not reflect any proper metallic radiance. They are widely scattered over the warmer regions of the globe, extending far into the southern temperate zone, but scarcely appearing beyond the tropic on the north side of the Equator. The species, which are exceedingly numerous, are for the most part very local; every large island, in the East and West Indies, and even in the groups of Polynesia, having kinds peculiar to itself. The largest and most richly coloured are the Macaws of South America and the Antilles.

BLUE AND YELLOW MACAW

The food of this Family consists almost exclusively of fruits; to which are added, by some of the Australian species in particular, the succulent parts of vegetables, bulbous roots, and unripe grain, when in a soft and milky condition. The grasping power of the foot is commonly used for the carrying of food to the beak, as if it were a hand; and the great mobility of the mandibles, aided by the fleshy tongue, enables the bird to discuss its food with much skill and discrimination, even to the performance of such a feat as Mr. Martin mentions as having often seen: "the clearing of the inside of a fresh pea from the outer skin, rejecting the latter; the whole process performed not only with facility, but with the greatest delicacy of manipulation, if this term be allowable."[5]

Parrots are monogamous; that is, a single male attaches himself to a single female; the eggs are deposited in the holes of decayed trees, or in the centre of the monstrous nests, so common in the tropics, formed by Termites, the crisp, earthy walls of which are easily chiselled away by the strong beaks of these birds. They associate in numerous flocks, whose flights from tree to tree present the most brilliant appearance, as the rays of a tropical sun glance from their gorgeous backs and wings. Their voices are loud and harsh; and of most of the species the screams have a piercing and grating character almost intolerable. Yet these are capable of wonderful modulation; the power which is possessed by many species of imitating the words of human language, the notes of vocal music, the calls of animals, and almost any sounds articulate or inarticulate, is well known; especially as developed by their extreme docility and memory, in the education of a state of captivity. This faculty is possessed by the various genera, however, in very different degrees.

Extraordinary examples of the imitative talent in these birds are on record, combined in some instances, at least, with what looks so like intelligence as to cause surprise and admiration. We quote the following interesting account from the "Gleanings" of Mr. Jesse, the more readily as that accurate observer seems, from his introductory remark, in some degree to authenticate the marvellous statement.

After speaking of the renowned Parrot belonging to Colonel O'Kelly, Mr. Jesse proceeds thus:—"There is another Parrot, which is occasionally brought from Brighton to Hampton Court, that appears to equal it in intelligence and power of imitation. I had seen and heard so much of this bird, that I requested the sister of its owner to furnish me with some particulars respecting it. The following is her lively and brilliant account of it:—

'As you wished me to write down whatever I could collect about my sister's wonderful Parrot, I proceed to do so, only premising that I will tell you nothing but what I can vouch for having myself heard. Her laugh is quite extraordinary, and it is impossible to help joining in it oneself, more especially when in the midst of it she cries out, "Don't make me laugh so. I shall die, I shall die;" and then continues laughing more violently than before. Her crying and sobbing are curious; and if you say, "Poor Poll! what is the matter?" she says, "So bad! so bad! got such a cold!" and after crying for some time will gradually cease, and making a noise like drawing a long breath, say, "Better now!" and begin to laugh.

'The first time I ever heard her speak, was one day when I was talking to the maid at the bottom of the stairs, and heard what I then considered to be a child call out "Payne! (the maid's name) I am not well, I'm not well!" and on my saying, "What is the matter with that child?" she replied, "It's only the Parrot; she always does so when I leave her alone, to make me come back;" and so it proved for on her going into the room the Parrot stopped, and then began laughing, quite in a jeering way.

'It is singular enough, that whenever she is affronted in any way, she begins to cry, and when pleased, to laugh. If any one happens to cough or sneeze, she says, "What a bad cold!" One day, when the children were playing with her, the maid came into the room, and on their repeating to her several things which the Parrot had said, Poll looked up, and said, quite plainly, "No, I didn't." Sometimes, when she is inclined to be mischievous, the maid threatens to beat her, and she says, "No, you won't." She calls the cat very plainly, saying, "Puss! puss!" and then answers, mew: but the most amusing part is, that whenever I want to make her call it, and to that purpose say, "Puss! puss!" myself, she always answers mew, till I begin mewing, and then she begins calling puss as quick as possible. She imitates every kind of noise, and barks so naturally, that I have known her to set all the dogs on the parade at Hampton Court barking; and the consternation I have seen her cause in a party of cocks and hens, by her crowing and clucking, has been the most ludicrous thing possible. She sings just like a child, and I have more than once thought it was a human being; and it was ridiculous to hear her make what one should call a false note, and then say, "Oh, la!" and burst out laughing at herself, beginning again quite in another key. She is very fond of singing "Buy a Broom," which she says quite plainly; but in the same spirit as in calling the cat, if we say, with a view to make her repeat it, "Buy a broom," she always says, "Buy a brush" and then laughs, as a child might do when mischievous. She often performs a kind of exercise, which I do not know how to describe, except by saying that it is like the lance exercise. She puts her claw behind her, first on one side and then on the other, then in front, and round over her head, and whilst doing so, keeps saying, "Come on! come on!" and, when finished, says, "Bravo! beautiful!" and draws herself up. Before I was as well acquainted with her as I am now, she would stare in my face for some time, and then say, "How d'ye do, ma'am?" this she invariably does to strangers. One day I went into the room where she was, and said, to try her, "Poll, where is Payne gone?" and, to my astonishment, and almost dismay, she said, "Down stairs." I cannot, at this moment, recollect anything more that I can vouch for myself, and I do not choose to trust to what I am told; but from what I have myself seen and heard, she has almost made me a believer in transmigration.'"[6]

The species alluded to in this sprightly note, Mr. Jesse has not named; we may conjecture it to have been the Grey African Parrot (Psittacus erythacus, Linn.), as that species is the most renowned for its powers of imitative speech, and is the most commonly kept in captivity. We shall illustrate the Family, however, by a genus of ancient renown.

Genus Paljeornis. (Vig.)

The Ring Parroquets, as the birds of this genus are termed, are distinguished by having the beak rather thick; the upper mandible dilated, the upper part (culmen) round; the lower mandible broad, short, and notched on the margin. The wings are moderate; the first three quills nearly equal, and longest; the outer webs of the second, third, and fourth, gradually broader in the middle. The tail is graduated; that is, the feathers diminish in length from the centre outward; the middle pair much exceed the rest in length, and are very slender. The feet are short and weak, the claws rather slender, and hooked. The general form is taper and elegant, the plumage smooth and silky: the ground-colour is usually green, sometimes merging into yellow; the neck is marked with a narrow line running round it like a collar.

The accounts we find in the ancient Greek authors, of Parrots known to them, refer to some species of this beautiful genus, as we gather from their descriptions. Some three or four kinds they appear to have been familiar with, which were first introduced into Europe at the time of the conquest of India by Alexander the Great, and one of which has been named in commemoration of him, Palæornis Alexandri. In their native regions, we are informed, they were the favourite inmates of the palaces of princes, and on their introduction

ALEXANDRINE PARROQUET

into Greece, whence they soon found their way to Rome,—soon came into general and deserved estimation, for the symmetry of their form, the grace and elegance of their motions, the beauty of their colours, their great docility, and imitative powers, and their fond attachment to those by whom they were domesticated and treated with kindness. Amid the luxury of Rome, the "Indian Bird" was kept in cages of the most costly materials, nor was any price, however great, deemed extravagant, or beyond its value.

The naturalists and the poets are eloquent on the varied attractions of these charming birds, descanting with admiration on the brilliant emerald plumage, the rosy collar of the neck, and the deep ruby-red hue of the beak. The species with the whole head of a changeable blossom-colour, we may reasonably infer, were unknown to them, for we cannot imagine they would have been silent on so conspicuous a feature of loveliness. Modern research has made us familiar with some eleven or twelve species, which are as generally favourites with us as with their early classical admirers. They are spread over the Indian continent and Archipelago, from the foot of the Himalaya mountains to the northern coasts of Australia.

The Alexandrine Parroquet has the general plumage of a beautiful green hue; the collar which adorns the neck is bright red, and a spot of dark purplish red marks the shoulders; the throat and a band between the eyes are black; the beak is of a rich ruby tint. The large island of Ceylon, the Taprobane of the ancients, is the principal resort of this beautiful species at this day; and it was from this island that it was first sent to the Macedonian conqueror whose name it bears. In captivity it is an affectionate and engaging bird, courting the notice and caresses of those whom it loves. It readily learns to pronounce words with considerable distinctness.

Family III. Picidæ.

(Woodpeckers.)

Some of the distinctive peculiarities of this strongly marked Family have been incidentally presented to the reader, in tracing the affinities of the Parrots, but we will now detail them more at length. The Woodpeckers are the most typical birds of their Order, for their whole organization is rendered subservient to the particular faculty of climbing, and hence they are eminently Scansores.

The feet are very short, but of unusual strength; the rigid toes diverge from a centre, two pointing forward and two backward; and the claws are large, much curved, and very hard and sharp. The bones which form the base of the tail are large, and bend downward in a peculiar manner, so that the tail feathers do not, as in other birds, follow the line of the body, but are thrown in beneath it, their points pressing against the surface on which the feet are resting: and as the shafts of the tail-feathers are remarkably stout, rigid, and elastic, and are produced into stiff points, the barbs also being stiff and convex beneath, a powerful support is gained in the rapid perpendicular ascent of the bird up the trunks of trees, by the pressure of this powerful organ against the bark. Another peculiarity observable in the structure of the "Woodpeckers, and one admirably adapted to their habits, is the small size of the keel of the breast-bone. "Moderate powers of flight," observes Mr. Yarrell, "sufficient to transport the bird from tree to tree, are all that it

GREAT SPOTTED WOODPECKER.

The beak is hard and compact in its texture, in some species nearly resembling ivory, stout at the base, and tapering, with angled sides, to the point, which is sharpened to an edge, like a small chisel; or perhaps, the whole form may be likened to a short but stout iron nail with a flattened point. The value and efficiency of this organ will be apparent when the economy of the bird is known; it obtains its food, consisting of the larvæ of wood-boring insects, by chiselling away the bark and surrounding wood, until the subtle grub is exposed. The head, then, acts as a hammer, of which the beak is the face or point, and the curved neck the handle, and being moved by muscles of great energy, the sharp and wedge-like beak-tip is propelled against the tree in a succession of strokes given with extraordinary force and rapidity.

But as the labour required actually to chisel out every grub on which the Woodpecker subsists, would be immense, effective as its weapon is, and rapid as is its execution, there is yet another admirable contrivance which we must notice, by which the prey being once exposed, is dragged from his tortuous hiding-places, and inmost crevices. The tongue is tapered to a slender horny point, and its length is extraordinary: for it passes behind into two cartilaginous filaments, which passing under the chin, one on each side of the throat, go completely round the back of the head, and meeting at a point on the forehead, are there inserted into the skull. These branches being highly elastic, free through their whole length, except at the very extremity, and moved by proper muscles both of extension and retraction, are capable of being alternately lengthened and shortened, by which motion the horny tip of the tongue is propelled far beyond the point of the beak, and drawn in again, with a rapidity almost greater than the eye can follow.

SKULL OF WOODPECKER.

Add to this, that there is on each side of the head a very large gland, which secretes a glutinous substance; this gland being embraced and compressed by the action of the muscle that protrudes the tongue, the viscid matter is poured out upon the sides of the tongue as it is thrust forth, and this is sufficiently adhesive to attach small insects, such as ants, small grubs, beetles, &c., which are quickly drawn in and swallowed. But as many of the boring larvæ are too heavy thus to adhere, and would hold on by their tuberculous feet, or by their strong jaws, the capture of such is effected by the horny tip of the tongue being set with numerous fine barbs on each side, pointing backwards; the fine point readily pierces the skin of the insect, the barbs yielding as it enters, but when once within it cannot without much force be withdrawn, the barbs having expanded within the skin, and so the insidious grub, despite his efforts to maintain his tenancy, is dragged forth by the powerful contraction of the Woodpecker's elastic tongue.

And here let us pause a moment, and turn our thoughts from the bird before us to the Almighty Lord God, who created it for His praise; from the beautiful contrivances we have been admiring, to the Eternal Mind whose wisdom designed, and whose skill executed them. "For the invisible things of Him from the creation of the world are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even His eternal power and god-head;" so that we should be without excuse, if, discerning such wondrous proofs of the fatherly love of God even to his irrational creatures, we "glorified Him not as God, neither were thankful."

The Woodpeckers are widely scattered over both continents; no representative of the form has, however, been discovered in Australia. They chiefly affect the forests, and are among the comparatively few birds that do habitually prefer their solemn sylvan recesses. Their flight is weak and undulating; their voices loud, harsh, and sudden. They lay their eggs and bring up their young in capacious chambers, which are hollowed out of the trunks of trees by the means of their powerful beaks. Their compact, well-built form indicates strength rather than grace: their prevailing hue is black, often handsomely spotted with white, and varied with brilliant red, the latter especially upon the head. Our commonest British species has a yellowish-green for its prevailing colour, instead of the more sombre ordinary hue.

Genus Picus. (Linn.)

The typical Woodpeckers have the beak perfectly wedge-shaped, cylindrical, the upper edge straight, the lateral ridges removed from the culmen. The outer hind toe is longer than the outer fore one: the wings are somewhat lengthened and pointed, with the third quill longest. The colours of the plumage are chiefly black and white, the latter arranged on the upper parts in large patches or bars. The genus is distributed over both hemispheres.

The Greater Spotted Woodpecker (Picus major, Linn.), though not quite so common in our island as the Green Woodpecker (Brachylophus viridis, Linn.), is more widely spread, extending even to the northern extremity of Scotland and to Ireland. It is found also in all parts of the continent of Europe, from the pine forests of Norway, to the orange-groves of Italy.

This species, which in some of the counties of England is called the Witwall, the Wood-pie, and the French-pie, is about as large as a Blackbird, but of a stouter form. The colour of the upper parts is black, marked on the head, neck, and shoulders with large patches of white, and chequered on the wing-quills with square white spots in alternating bars; the hind head is of a rich crimson hue; the under parts are of a dull white, except the vent and under tail coverts, which are red.

The Spotted Woodpecker is much more strictly an arboreal bird than the green species. It climbs with great ease and dexterity, traversing the

SPOTTED WOODPECKER.

In the last edition of Pennant's "British Zoology," it is stated that this species, by putting the point of its beak into a crack of the limb of a large tree, and making a quick tremulous motion with its head, occasions a sound as if the tree were splitting, which alarms the insects, and induces them to quit their recesses: this it repeats every minute or two for half an hour, and will then fly to another tree, generally fixing itself near the top for the same purpose. The noise may be distinctly heard for half a mile. This bird will also keep its head in very quick motion while moving about the tree for food, jarring the bark, and shaking it, at the time it is seeking for insects.

Like the rest of this Family, the Spotted Woodpecker inhabits holes which it has chiselled out of the solid timber of trees; and in these warm, and weather-tight chambers, the females perform the business of incubation. Colonel Montagu relates the following instance of the pertinacity with which the bird remains in her domicile while sitting:—"It was with difficulty the bird was made to quit her eggs; for, notwithstanding a chisel and mallet were used to enlarge the hole, she did not attempt to fly out till the hand was introduced, when she quitted the tree at another opening. The eggs were five in number, perfectly white and glossy."

Family IV. Cuculidæ.

(Cuckoos.)

"So faintly," observes Mr. Swainson, " is the scansorial structure indicated in these birds, that but for their natural habits, joined to the position of their toes, we should not suspect they were so intimately connected with the more typical groups of the tribe as they undoubtedly are. They neither use their bill for climbing, like the Parrots, nor for making holes in trees, like the Woodpeckers; neither can they mount the perpendicular stems like the Certhiadæ or Creepers; and yet they decidedly climb, although in a manner peculiar to themselves. Having frequently seen different species of the Brazilian Cuckoos in their native forests, I may safely affirm that they climb in all other directions than that of the perpendicular. Their flight is so feeble from the extreme shortness of their wings, that it is evidently performed with difficulty, and it is never exercised but to convey them from one tree to another, and these flights in the thickly wooded tracts of tropical America are of course very short; they alight upon the highest boughs, and immediately begin to explore the horizontal and slanting ramifications with the greatest assiduity, threading the most tangled mazes, and leaving none unexamined. All soft insects inhabiting such situations lying in their route become their prey, and the quantities that are thus destroyed must be very great. In passing from one bough to another they simply hop, without using their wings, and their motions are so quick, that an unpractised observer, even if placed immediately beneath the tree, would soon lose sight of the bird. The Brazilian hunters give to their Cuckoos the general name of Cat's-tail; nor is the epithet inappropriate, for their long hanging tails, no less than their mode of climbing the branches, give them some distant resemblance to that quadruped. I have no doubt that the great length of tail possessed by nearly all the Cuckoos is given to them as a sort of balance, just as a rope-dancer, with such an instrument in his hands, preserves his footing when otherwise he would assuredly fall. Remote therefore as the Cuckoos unquestionably are from the typical Scansores, we yet find the functions of the tail contributing to that office [i. e. climbing], although in a very different mode to that which it performs among the Woodpeckers, the Parrots, and the Creepers. The structure of the feet, as before observed, is the only circumstance which would lead an ornithologist to place these birds among the Climbers, supposing he were entirely unacquainted with their natural history properly so called, or with their close affinity to the more perfect Scansores. The toes, indeed, are placed in pairs; that is, two directed forward, and two apparently backward; but a closer inspection will shew that the latter are not strictly posterior, and that they differ so very materially from those of the Picidæ (the preeminently typical Family of the Climbers), as clearly to indicate a different use. The organization of the external posterior toe of all the Woodpeckers, Parrots, and Toucans renders it incapable of being brought forward, even in the slightest degree; whereas, in the Cuckoos, this toe can be made to form a right angle with that which is next it in front, from which circumstance it has been termed versatile; this term, however, is not strictly correct, inasmuch as the toe cannot be brought more than half-way forward, although it can be placed entirely backward.... The Cuckoos, in fact, are half perching, half climbing birds, not only in their feet, but, as we have seen, in their manners. No one, from seeing them alive, would suppose they were truly scansorial birds; and yet it is highly probable that this singular power of varying the position of one of their toes, gives them that quickness of motion and firmness of holding, which accompanies the habit just mentioned."[8]

The technical characters of the Family, besides those already spoken of, are a beak of medium length, rather deeply cleft, both mandibles compressed and more or less curved downward; the nostrils exposed; wings for the most part short, but the tail lengthened. Their skin is remarkably thin, but the plumage, especially on the back and rump, thick and compact.

The intertropical regions, both of the Old and the New World, afford the greatest number of species to this Family; many, indeed, penetrate into the temperate zones, but it is only as summer visitants, the greater number retiring almost before the heat of the season has sensibly abated. Their food consists largely of insects, principally those which are soft-bodied, as spiders, moths, and caterpillars, varied in many cases with berries and other fruits; and some of the large species will occasionally prey on mice, reptiles, and the eggs and young of birds. Their voices are generally loud and croaking; often consisting of a repetition of a single note in long succession. Their plumage is generally of subdued, but chaste and pleasing hues, with more or less of reflected lustre; the long tail is often graduated, and handsomely barred with black and white. Africa and the islands of the Indian Ocean produce some small species, the plumage of which is radiant with emerald-green, purple, and bronzed reflections.

Genus Cuculus. (Linn.)

Of this extensive genus the distinctive characteristics are the following: the beak is broad and rather depressed at the base, with the culmen curved, and the sides compressed towards the tip, which is entire and acute; the nostrils are placed on each side of the base, in a short, broad, membranous groove, with the opening round and exposed; the wings comparatively long and pointed, the third quill longest; the tail long, usually graduated, the outmost feather on each side much shorter than the rest; the tarsi are very short, feathered below the heel, the exposed part covered with broad scales.

The species are confined to the eastern hemisphere, over the warmer parts of which they are extensively and numerously distributed: two only occur in Europe, the one as a constant, the other as an occasional summer migrant from the sunny regions of Africa: most of the species, indeed, are more or less migratory. Their habits are recluse and solitary, frequenting woods, or at least places where thick trees abound; and they are wary and jealous of the approach of man. They do not fly with much apparent power, but content themselves, in common, with gliding on steady wing from one tree to another. At the season of migration, of course, they must be able to sustain a flight protracted for many leagues. The food of these birds consists largely of caterpillars, especially the thick hairy larvæ of the greater moths; before swallowing them, the Cuckoo is said to cut off the hinder extremity of the body with its beak, and by repeated jerks to free the insect from the intestinal canal. The note is loud, and uttered frequently in a lengthened and melancholy manner, especially early in the morning, and at the approach of evening; sometimes it is emitted even in the night.

The most remarkable circumstance in the economy of this genus,—and one which, as far as is yet known, is common to the whole of its numerous and widely-spread species,—is that the female makes no nest for its own economy, but deposits its eggs in the nests of small birds, always selecting such as are insectivorous, and for the most part such as belong to the Dentirostral tribe. The whole care of "hatching and rearing the young, is now left to the foster-parent; and as the wants of so large an intruder, additional to those of their own offspring, would be more than the efforts of the selected nurses could supply, an instinct is implanted in the young Cuckoo, by which, even from the very day of its birth, it is impelled to eject from the nest the rightful tenants of it. This, in the case of our well-known Common Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus, Linn.),–whose habits are better known than those of others,—is effected by the newly-hatched Cuckoo insinuating the hinder part of its body under the young of the foster-parent, and raising it upon its loins, which are remarkably broad, and even hollowed, when, lifting it to the rim of the nest, it deliberately throws it overboard; nor does it cease until it finds itself the sole occupant of the nest, and the sole recipient of the attentions of those whose children it has thus ruthlessly murdered. In this country the Hedge Sparrow, the Pied Wagtail, the Pipit, and the Robin, are the species most frequently chosen by the Cuckoo to be the nurses of her offspring; and it must be

CUCKOO

In May—He sing all the day;

In June—He change his tune;

In July—Away he fly;

In August—Away he must.

The double note of the male Cuckoo is known to every one; and there are few, in any degree familiar with rural sounds and associations, who do not feel a thrill of pleasure when it falls upon their ear. But more especially when, for the first time in the season, it is heard in a lovely Spring morning, mellowed by distance, borne softly from some thick tree, whose tender, and yellow-green leaves, but half-opened, are as yet barely sufficient to afford the welcome stranger the concealment he loves. At such a time it is peculiarly grateful; for it seems to assure us that, indeed, "the winter is past, the rain is over and gone; the flowers appear on the earth, and the time of the singing of birds is come."

"Sweet bird! thy bower is ever green,

Thy sky is ever clear;

Thou hast no sorrow in thy song,

No winter in thy year!"

The Cuckoo is a bird of much elegance: the plumage of the superior parts is of a chaste bluish-grey tint; the under parts are white, marked on the belly with transverse bars of grey.