Once a Week (magazine)/Series 1/Volume 2/The ghost's night-cap

THE GHOST’S NIGHT-CAP.

Just thirty years ago—that is to say in the month of November, 1829—an English family, named Daubville, was in occupation of an old Italian villa on the Leghorn Hills. It is to be regretted that the Daubvilles wrote "Honourable" before their name, because any reader with a soul above that animula vagula, blandula, which animates the tidy form of an Irish waiting-woman, must be so heartily sick of the aristocratic eidolons which pervade our modern English novels, that he would feel a history of Mr. Stubbs the tallow-chandler, an ineffable relief from the monotonous insipidity of the purple. But, as in all essentials the following narrative is true, nothing being altered but the name of the family in which it occurred, it is necessary to state or admit that the Daubville family consisted of Lady Caroline Daubville, a widow—her two daughters, Margaret and Eliza, then with her—a son John, absent at Oxford—and of Lady Caroline’s brother-in-law, also called John, who at the moment our story opens was driving up the avenue of the Villa Ardinghelli on a visit to his sister and nieces.

The two young ladies ran down-stairs to welcome their uncle. The Honourable John Daubville was tall and spare, somewhat above fifty years of age; very bald, and with a stereotyped sneer upon his lips. A kindly-natured man in reality, he prided himself upon his scorn for all forms of superstition, all prejudice, and upon his profound disbelief of all supernatural interference with the order of nature. He had trained his mind carefully in the school of the French Encyclopedists; and Voltaire, in particular, was his great authority. The universe was a huge machine—the globe a somewhat smaller one—men and women were machines with certain functions and powers; and he—the Honourable John Daubville—was a machine of a superior class. He admitted gravitation, he bowed to centrifugal force; he detested an east wind, and he rejoiced in ortolans. All things above or beyond the experience of every day life he dismissed summarily as impossible. This was the gentleman who was conducted up-stairs, by the two young ladies, to the presence of Lady Caroline.

“And how are you, my dear sister, in this best of all possible worlds? I am glad to find you in such good quarters, and hope you will be able to find a corner in which your poor brother may repose after the fatigues of the London season last summer, and an autumn in Paris.”

“Well, brother, well,” replied Lady Caroline, “and I am glad that the villa we have chosen meets with your approbation. Right glad are we to see you: but—but—” Lady Caroline paused with a made-up smile.

“Eh! What do you mean? Is there not a room for me here?”

“Yes, dear brother, there is not only one room, but two rooms. The only objections I know to the first, are four. It is over the stable, dark, small, and looks on the court-yard. The second is a noble chamber, with a glorious view of the Mediterranean; but—but—I say again—”

“But what?”

“There is a report that it is haunted.”

“Pooh!” replied Mr. Daubville, with a look of the most ineffable contempt; “no doubt there will be room for both of us. So the ghost does not insist upon sharing my bed I shall make no objection, and indeed if he does—By the way, is it he or she?”

“He, John, he,” replied Lady Caroline, with a look worthy of Lucretia at her spinning-wheel.

“Umph? Well, if he does, being a ghost it is no great matter. Only there must be an arrangement between us as to our hours of getting up; for, as I have always understood, ghosts are in the habit of rising at cock-crow. Now, unless you could make away with all the cocks in the neighbourhood save one, and shut that one up in a dark closet till 10 a.m., and then open the door. Eh?”

“Well, well, John,” said Lady Caroline, “I see you are as sceptical as ever.”

Mr. Daubville made a profound bow.

“And so Margaret and Eliza shall conduct you to the Haunted Room.”

“By all means,” replied her brother. “I dare say your ghost and I can get on well together.”

The room into which Mr. Daubville was conducted by his nieces, had obviously been used of old as the principal sleeping apartment of the villa. It was very large, and contrary to the received opinions with regard to haunted rooms, was very cheerful and bright. Three large windows looked out upon, or rather towards the sea, for the Villa Ardinghelli stood upon the slope of a hill, distant about three-quarters of a mile from the sandy beach. Through these windows the western sun was now pouring his rays, and illuminating the mysterious chamber. At one end of the room was a huge bed, such a bed as is only found in Italy, with the exception of that one specimen which still exists at Ware in Hertfordshire. The hangings of the bed were of old discoloured tapestry, such as a ghost might reasonably enough expect to find in any apartment devoted to the use of a lodger of his class. The bed was not only enormously broad, but high in proportion, so that it would have required considerable gymnastic powers to have reached the table land on the summit, but for a flight of steps which stood by its side. Mattrass after mattrass stuffed with the leaves of the Indian corn had been piled up, the one on the other, in order that the stately pile might attain its due proportions. Over against the bed was a large open chimney—the hearth fitted up with “dogs” of quaint old workmanship. Great blocks of fir, and the pine-cones picked up in the adjacent woods, were the fuel with which it was fed. There was a clumsy but richly-carved dressing-table placed facing the centre window, with a large mirror behind it, and well-nigh opposite this, against the fourth and remaining wall of the room, a black chestnut wardrobe, large enough to hold half-a-dozen people standing upright. Now it must not be supposed that the great bed with its hangings, the toilette-table with its mirror, the open chimney with its dogs, the wardrobe with its capabilities—though these might fairly be considered ghostly furniture—were sufficient to communicate to the apartment the feeling of a haunted room. It was so large that if the articles named did not appear quite lost in it, at any rate they seemed to be the right things in the right place. The care of the young ladies had provided three or four small tables, unquestionably of modern fashion and make, covered over with those little knick-knacks which look so charming, and which are so useless, but without which ladies do not seem to consider that bed-rooms in country-houses can be complete. A few vases of flowers contributed their share of brightness, and unwholesomeness, to the Haunted Room.

“Well, my dear girls,” said Mr. Daubville, after a glance round the room, “at any rate, I see nothing very terrible here. Your ghost must be of simple and inoffensive habits; and there is plenty of room, as I am happy to observe, in that portentous bed for us both. No window curtains either; nothing but the open shutters outside—all the better: less cover, Miss Eliza, for young ladies who might be disposed to play tricks at a poor old credulous uncle’s expense.”

“Tricks! I would not come near the place after sun-down for ten thousand pounds.”

“Hum! my dear, large sum—very. But let us have a peep into this wardrobe. There, if anywhere, we shall find the solution of the enigma in case of disturbance. Nothing in there but three racks for clothes: back all sound, and clear of the wall Not much danger there,—dressing-table without furniture, frills, or fooleries—right again—not like a conjuror’s table with all the apparatus underneath. Frame of the bedstead three inches from the ground. Egad, if anybody slips beneath that, he can’t be a body—must be a ghost—all the better.”

“Oh, uncle!” said Miss Margaret, “it’s quite awful to hear you talk so. Who wouldn’t exchange a cold, nasty, thin ghost for a good, solid, comfortable human housebreaker, with—perhaps, a flannel waistcoat on.”

“Not I, for one, Maggie. Housebreaker might make a ghost of me; ghost couldn’t turn me into a housebreaker. Let me have a look up the chimney—cross-bars—all right, again—besides, good fire, smoke him out—make the place too hot to hold him. Only one point more to guard—excuse my vigilance, but old yeomanry officer,—know what I’m about. Must take care nobody gets in at the window. Old soldier—mustn’t be caught napping. Splendid, magnificent indeed.”

“Yes, we thought you would enjoy the view.”

“It isn’t the view, you foolish girl; look at the drop—sixty—ay! I dare say seventy feet sheer down. How’s that? we only came up one pair of stairs. I see—house stands on a terrace—carriage drove in back way. Very good, indeed—no danger from without—puzzle them to get up that wall—not a balcony anywhere? No—that’s all right. Young ladies, Uncle John will undertake to make good the place against all attacks from ghosts actual, or ghosts that are to be. And now, my dear girls, if you will kindly rejoin your mother, I will make my little preparations for dinner.”

The dinner was over—the cloth was drawn, and Mr. Daubville proceeded to give the ladies an abstract of how the fashionable babies in London had been born, how the fashionable couples had been married, and how the fashionable people whose time had come, had passed away beyond the further notice of the beau monde. There was, however, throughout the evening, something forced and unnatural in the spirits of the party. The ladies appeared to look upon Uncle John as you would look upon a dear friend who was about to go up in a balloon, or down in a diving-bell, or to lead a forlorn hope, or engage in any other very perilous enterprise, from which there was very little chance that he would return alive. They would put too much sugar in his tea; place stools for his feet when he required none, and smother him with a thousand feminine attentions, which at length became actually oppressive. Uncle John at last started up, saying:—

“My journey to-day has been long and fatiguing. Pray excuse me, dear Caroline, if I take my candle, and retire for the night.”

At this moment, one of the window-shutters blew open with a loud crash. Margaret, who was presiding over the tea-table, in her sudden fright seized the handles of the tea-urn for support; the tea-urn gave way, and upset its scalding contents upon the accurately shaved hind-quarters of Lady Caroline’s favourite poodle, Benvenuto. The dog immediately retreated under his mistress’ chair, with one long despairing yell, like the pitch-pipe in a country church. Eliza threw herself on her knees before her mother, which touching movement of filial confidence was met in a somewhat eccentric manner by that lady, who cuffed her violently, while she lavished upon her at the same time expressions of the most devoted affection. Mr. John Daubville alone retained his presence of mind, calling out:—

“It is only the dog,” and began kicking Benvenuto under the chair. Benvenuto, whether aroused by the personal indignity offered to him, or smarting under the stimulus of his recent hot bath, or really under the impression that Mr. Daubville was the cause of the confusion, fastened his teeth on that gentleman’s calf till his eyes watered with pain. At last, but not for some time, order was restored, and Mr. Daubville, desirous of regaining the position of a man of cool head and unflinching nerve, from which he had somewhat fallen, with one vigorous kick disengaged his leg from Benvenuto’s teeth, and walking over to the window, soon ascertained that it was only the fastening of the shutter that had given way under the pressure of a sudden gust of wind.

“No, John,” said Lady Caroline. “It is not the wind, it is a warning! The Spirit of the Haunted Chamber is abroad, and bids you not to intrude upon the apartment sacred to his repose.”

“My dear sister,” said Mr. Daubville, “nonsense; in that room I will sleep to-night, though fifty thousand ghosts should be my bed-fellows.”

So saying, Mr. Daubville took up his candle and retired. His retreat would have been dignified, but that Benvenuto, who did not at all seem to consider the dispute had ended in a manner satisfactory to his own feelings, kept on making short rushes at him, thus compelling him to face about, and contest every inch of ground to the door.

There was a fine wood fire smouldering on the hearth of the Haunted Chamber, as Uncle John entered it to take up his quarters for the night. The great log had long since accomplished all that it could in the way of crackling, and blazing, and sending forth tongues of fire; and had now concentrated its efforts upon the production of a steady, rich glow. The room looked red, save at the extremity where the great bed stood; this portion of the room was so distant from the hearth, that it did not take the colour from the fire; but was so dark that you could scarcely distinguish the objects it contained. The huge bed looked indeed like a heavy shadow. It was very odd, but somehow or another Uncle John began to feel uncomfortable. The candle scarcely produced any appreciable effect either upon the red glow or the gloom.

“Ghosts,” he muttered to himself. “Pooh! pooh! not to be caught that way. I wish that confounded dog had been a ghost. However, it’s as well to guard against what they call fun—so I will load one of my pistols with powder in order to frighten any one who might be disposed to play a trick at the old gentleman’s expense, and another with powder and ball in case an intruder of a different description should drop in.” So said, and so done. “And now,” continued Uncle John, “I will put one at the right hand of the bed—that shall be the business pistol—and one at the left, for the benefit of practical jokers. Now for it—rather dark down there—well, well, what an old fool I am—ha, ha, ha! place the pistols out of my reach at once indeed—not such a simpleton as that—but I’ll take one—the one loaded with powder and ball—yes, powder and ball, and reconnoitre my quarters.” Pronouncing these last words very emphatically, Uncle John struck up with great vigour, but considerably out of tune, the old poacher’s anthem.

It’s my delight of a shiny night in the season of the year,

and marched up to the old wardrobe with his pistol cocked in one hand, and the lighted candle in the other. The wardrobe was as empty as when he had inspected it. The bed with its heavy tapestry hangings was visited in the same manner.

“Mere matter of form,” remarked Uncle John, “but old officer—must go my rounds—all habit.”

Obviously more comfortable in his mind, he now proceeded to make his preparations for the night; but the only point in these on which any stress need be laid, was the care which Mr. Daubville displayed in putting on a heavy cotton night-cap; one of the good old sort, which stood upright on the head, and was crowned at its apex with a tassel. For further security, and perhaps not altogether without a lingering sentiment of the beautiful, Uncle John proceeded to bind round his head a pink ribbon.

“Had the hint from the old Vicomte de Pituite. Combination of utility and elegance. Ah! wish I’d turned gray instead of bald. There are so many dyes of approved merit; but here I am as bare as a billiard-ball. Oh! for the sensation of brushing one’s hair! Those young dogs, they don’t know the blessing they enjoy. One hour now of being small-tooth-combed by a rough-handed nurse-maid, with one’s thick elfin locks matted and tangled. Talk of the first kiss of first love—nothing to—

That pleasing agony which schoolboys bear

When nursemaids small-tooth-comb their shaggy hair.

Not so bad, that, and now to bed.”

With some little trouble Mr. Daubville succeeded in performing the feat of ascending his lofty couch, but the weight of his body on the many mattrasses, stuffed as they were with the crackling leaves of the Indian corn, produced such an appalling noise, that he sat upright for some moments with a pistol in each hand, and a look of firm defiance in his face, waiting for the attack, which never came. Understanding at length the real meaning of all this disturbance, he recovered from his alarm, and carefully depositing his pistols within reach of his hands, but beyond idle region marked out in his own mind as sufficient for tossing and turning about in his sleep, and placing the candlestick with a box of matches in the tray just at the edge of the bed, Uncle John blew out the light, and in a quarter of an hour was asleep.

Three or four hours passed away—nothing had occurred to arouse him to consciousness, but somehow or other he fell a dreaming. He was hunting walruses; he was in search of the Magnetic Pole—capital sport, and majestic pursuit—but it was all so cold—so very cold. Then a change came over his dream,—he was with Dante and his Mantuan guide slowly pacing the circles where the condemned spirits expiated their misdeeds in various forms of suffering. Then he himself was a wicked pope of the opposite line of politics to that of the strong party-man whose election-squibs were framed for eternity. He was condemned to lie for ever on a bed of molten lava, with his head in a huge block of ice. Strange to say the torture was bearable, although decidedly uncomfortable. “What shall I do for pocket-handkerchiefs,” thought Uncle John, “if this goes on? I shall never be able to get at my nose.” With one appalling sneeze he awoke; it was pitch dark, and he continued sneezing. His first act was to put his hands up to his head—his night-cap was gone!

“Eh! what is this? night-cap tumbled off, despite the ribbon—never knew that happen before. Where can it be?must strike a light and see.”

This was done; the sleeper was fairly awakened; he groped everywhere—behind the pillows—under the bedclothes; he craned over the sides of the bed—got up and searched everywhere. The night-cap was not to be found. It was very odd—he must have put it on before getting into bed; he had been bald since five-and-twenty, and whatever other duty he had neglected, he had never forgotten to put on a night-cap during all these years. What made matters worse just now was that the trunk containing his provision of night-caps, had not yet been brought up into his room. There was no help for it, but to make shift by tying a stocking round his head, and so to sleep again. He was aroused by a knocking at his door; a servant entered the room with hot water. It was broad daylight, and time to get up. The friendly stocking which he had tied round his head had fallen off in the night, but was lying on the pillow, and Uncle John had a most fearful cold in his head. The night-cap was not to be found!

When he got down to the breakfast-room he found Lady Caroline and her daughters waiting to welcome him with looks of fearful interest. Everybody save Benvenuto, tantæne animis cœlestibus, mindful of the feud of the preceding evening, appeared delighted to see him safe and sound.

“Did the Spirit of the Chamber pass before you in the night, dear John?” said Lady Caroline. “You look worn and wan.”

“Ah-tschoo! ah-tschoo! ah-tschoo!”

“Oh! dear Uncle, tell us all about it—have you seen the ghost?”

“Ah-tschoo! Confound the ghost! Oh! dear! ah-tschoo.”

“Dear John, it appears to me that you are suffering from catarrh; but at least you have escaped the dangers of the supernatural world.”

Mr. Daubville, with watery eyes, and many sneezes, related to them his adventure of the previous night; it was the strangest—the most unaccountable thing. He quite lost his temper when he found that he was unable to convince his sister and nieces that he had put on a night-cap at all; but was somewhat soothed when Margaret and Eliza, who were aware of his partiality for night-caps, told him that for months past they had been engaged in working for him a night-can, which would be to other night-caps as Milan Cathedral to other cathedrals. The presentation night-cap wanted but the tassel, which the young ladies were to procure that afternoon in Leghorn, and it would be ready next day.

“Well, my dear nieces—ah-tschoo—I am much obliged to you for your magnificent present, and still more for your—ah-tschoo—consideration for my comfort. This night I suppose I must put up with—ah-tschoo—one of the ordinary material; but at least to-night I shall be able—ah-tschoo!—to recover from this wretched but temporary ailment, and be in a fit condition to do justice to your—ah-tschoo—gift.”

The day passed away—the night came. Uncle John retired, and the next morning presented himself again at breakfast, in a paroxysm of sneezes, and this time in a most unmistakeable passion.

“Caroline, I don’t—ah-tschoo—understand this abominable practical joking. It’s too bad. I shall—ah-tschoo—suffer from neuralgia during the remainder of my—ah-tschoo—days!”

“Why, dear John, what is the matter?”

“The matter—ah-tschoo! The night-cap is gone again! Ah-tschoo! tschoo! tschoo!”

In order that this recital may be disencumbered from the history of Uncle John’s sneezes, it will be sufficient to say that he related, with much indignation, how he had taken the precaution on the previous night to summon one of the servants to his presence whilst he was preparing for bed. This servant—Pietro—known in the establishment as Pietro Grande, an old man, above all suspicion of participation in any practical joke, had seen the night-cap on Mr. Daubville’s head, when he got into bed—had extinguished his light—had left him in bed with the night-cap on; but morning came, and where was the night-cap? Uncle John would not believe but that somebody had entered his room in the night and stripped his sleeping head of its honours; indeed it was easy to gather from his manner that he believed his nieces to be at the bottom of the mischief. Certainly he had not locked his door. He could not suppose that any person in the house, certainly not any person who set any value on his health or comfort, would be so inconsiderate—so wanting in respect to him—so silly, as to take part in such a miserable trick. However, he must pay the penalty, but if he could but catch them! There was a savage twinkle about Uncle John’s eye as he sneezed out these last words which seemed to imply that even the stately Lady Caroline herself would fare but ill if he found her meddling with his night-cap: and there was a pistol, as our Irish friends would say, “convanient.”

The young ladies seemed to be perfectly aware that they were suffering under the suspicions of their uncle; but either they were consummate actresses, or they were entirely innocent of the trick which, as he supposed, had been played upon him. In the course of the afternoon the cold in the head got better—colds in the head do harden up in the middle of the day—and Margaret and Eliza brought to their uncle the presentation night-cap.

It was a magnificent article made of black velvet, heavily embroidered with gold. It was padded inside, and the ingenuity of the young ladies had even contrived a moveable strap to pass under the chin, fastening with a button at either side, and which might be either used or taken off at pleasure.

“I will button it on with the strap at night, dear girls,” said Uncle John, “and it would have been well if, on this gorgeous cap, had been inscribed the motto which goes with the iron crown of Lombardy, ‘Guai a chi me tocca!’ I think it will puzzle my friends of the two last nights to get this off my head.”

It was not a little remarkable that all recollection of the haunted room seemed to have passed away from the minds of all. There was something so homely and prosaic—so grotesque, so earthy of the earth, in all this discussion about night-caps lost, and to be lost, that a ghost with any kind of self-respect could not even have attempted to hold up his head in society where such subjects formed the staple of discussion.

It may be mentioned then that, on the third night of his stay at the Villa Ardinghelli, Uncle John actually put his feet in hot water, greased his nose, and partook of a copious basin of gruel in the haunted room. In the course of the day a blacksmith had been summoned from Leghorn who had fitted a heavy night-catch on to the door, and had led a wire round to the bed-head. A bell-rope dangled from this, by help of which Uncle John without moving from his snug place, in the bed, could either shut himself up in his castle or admit visitors at pleasure. He let fall the bolt, saw that his pistols were ready, as usual, to his hand (this time both were loaded with ball), and then determined to remain awake. This resolution he acted upon for some time, soothed with the warmth and pleased with the rich red light. Gradually all sounds in the house died away. Uncle John tried the repeater under his pillow; it marked half-past eleven; he fell a-musing upon wigs! should he now without any thought of imposing upon his fellow-creatures, but simply with a view to his own comfort, seriously entertain the idea of a wig—not of young hair, but of a colour appropriate to his time of life—regarding it merely as a—a—a permanent—cap? Uncle John fell asleep.

He knew not how long he had slept; but the same sensation of coldness as on the previous nights pervaded his sleeping frame, and settled finally in his head. He awoke—clasped his head: Powers above! could it be? The velvet night-cap was gone!

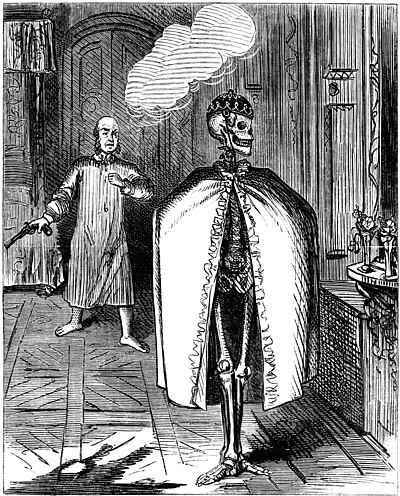

This time the night was not so far spent as it had been before when he had been roused from his slumbers by the abstraction of his caps. The fire was still burning, though now low, upon the hearth (a lurid red glow pervaded the room), but still there was an unnatual feeling abroad. Uncle John wanted to catch at his pistols; but his arms were glued to his sides, and his poor bald head grew wet with perspiration, When he moved, never so lightly, the crackling of the Indian corn-leaves underneath him was to him like the crack of doom. At last he could stand it no longer; he tried to shriek out “Who’s there?” at the top of his voice, as he would have cheered at the cover side in his younger days—his words came from him in a weak, childish treble. There was no reply. He sate up in bed, and the first object on which his eye rested, was a tall figure in what was apparently a white cloak, standing before the mirror with his black velvet cap on his head.

This sight immediately roused Uncle John’s indignation. He caught up his pistols, and, in bed as he was, called out:—

“I’ve got you at last; bring back my cap, this moment—this very moment.”

The white figure took no notice of the summons, but remained before the mirror, making the most fantastic bows and salutations to itself. You would almost have supposed it to be a dancing-master, practising a new minuet. Its attention, however, seemed to be chiefly devoted to the cap. Now it cocked it upon one side of its head, and stuck a hand upon its own side in a jaunty way; now it drew the cap well-nigh over its eyes with both its hands, and bowed its head backwards and forwards, like a Chinese Mandarin figure: then it thrust it well off the forehead in Pierrot fashion; but all this time Uncle John could never catch a glimpse of the face. Roused at length to an unbearable pitch of exasperation as the white figure seemed to evince symptoms of an intention to pull the tassel off—

“Now, take notice,” roared out Uncle John; “this pistol is loaded with ball, and I’m a nine-of-diamonds man, in solemn earnest. If you don’t bring that cap to this side of the bed, and surrender before I count three, I fire. One—two—three.”

The pistol exploded, but the draped figure treated the commencement of hostilities with the profoundest contempt, not to say derision. The only effect of the discharge was that it began turning its head round and round with great rapidity, like a dancing dervish in a paroxysm. The idea immediately occurred to Mr. Daubville, that the bullets had been drawn from his pistols; but, even so, it was strange that the figure would not turn round; and took no more notice of his existence than though he had been in his bachelor lodgings, in Norfolk Street, May Fair. He slipped out of bed with the other pistol in his hand, and stepped across to where the figure stood, still with its face to the mirror, determined to ascertain who the bold intruder might be. The gyrations of the head had ceased when Uncle John approached near enough to see over the shoulder of the figure into the mirror. As he caught the reflection, he saw that the velvet cap was upon a skull; that when the figure partly opened its drapery, it was a skeleton; and the drapery itself a shroud! In the midst of his agony of terror, he noticed particularly that two of the front teeth of the skull were deficient. Uncle John fired off his second pistol, the flash passed through the figure, lighting up the ribs, and the bullet shattered the mirror. The figure turned round, and appeared to take off the cap, and made a profound salutation to Uncle John, who sank insensible on the floor.

There was a noise in the passage outside; a calling from many voices; and amongst them the voices of Lady Caroline and her daughters were predominant. The door was broken open by the servants, and Uncle John was carried off to another apartment, and gradually brought back to consciousness. He seemed at first to have forgotten all about his adventures of the night; it was only when the circumstance of his having been found insensible on the floor of the Haunted Room was recalled to his memory, that he called out:

“The ghost—the ghost! Take me away from this accursed place. Take me away at once.”

The next morning, the Daubville family left the Villa Ardinghelli, and exchanged the neighbourhood of Leghorn for Florence. Uncle John could never be brought to speak of his adventures that terrible night in the Haunted Room.

*****

One day, in the following spring, the Daubville family, Unde John and all, were roaming about Florence, under the guidance of a learned Italian friend, who had taken upon himself to be their Cicerone round the antiquities of Florence. In the course of one of their wanderings, in a somewhat remote quarter of the town, they came to the church of San Teodoro; a church little visited by English travellers. There were two or three carriages in the piazza before the church.

“Ah! I remember,” said their conductor. “How fortunate we came here to-day. A tomb is to be opened, the tomb of a great hero in our Florentine history. Come along!”

Their guide hurried them into the church. As they were walking up the aisle, Lady Caroline whispered: “But whose tomb is it?”

Their conductor paused, waited till the whole party had joined up, and then, in that emphatic whisper peculiar to Italians, said:

“The tomb of Ambrogio dei Ardinghelli!” Uncle John followed the Abbé to the spot, when just as they came up the workmen had succeeded in heaving the marble lid off a sarcophagus. The lid was so ponderous that it had been necessary to use strong mechanical contrivances to move it. The by-standers crowded up; but only a few were allowed to approach at a time, and amongst these the place of honour was given to the English ladies. Margaret had no sooner looked in, than she shrieked out:—

“Uncle John’s night-cap!”

Uncle John himself pressed his way through the little crowd of spectators, clutched the side of the tomb with frantic grasp, and looked in. There lay the skeleton of Ambrogio with Mr. Daubville’s velvet night-cap on the grinning skull; his two cotton night-caps were by the side of the skeleton, somewhat dusty. In the tomb there were about a dozen other night-caps of various ages and fashions. Two front teeth were wanting in the skull.

Uncle John quitted the church with his party, and that evening related his story to his relations and their Italian friend. This gentleman had brought with him an extract from an old Florentine chronicler, which, as he said, would throw light upon the matter. Here it is:

“Now the skirmish having passed pleasantly, with great delectation to the noble knights and their horses, and the ground being fairly bestrewed with the bodies of the valiant combatants, ‘Where is Ambrogio?’ was the affectionate cry of his people, as they gallantly retreated at their utmost speed. At that moment Messer Ambrogio was lying on his back, unable to move from the weight of his armour, and his old enemy, Messer Buoncore dei Straccini, was kneeling on his chest—he was a heavy and worshipful lord—and tugging away at his helmet, into which he had been unable to introduce his dagger to finish the good lord’s existence, according to the merciful custom of knighthood, so cunning was the handicraft of the Spanish smith. At last the fastenings gave way, and Messer Buoncore saw with whom he had to do. ‘Quarter and ransom,’ cried Messer Ambrogio. Messer Buoncore swung the helmet round with his utmost strength, and with it struck Messer Ambrogio on the mouth, whereby two of his front teeth were smitten out, saying, ‘Ha, such quarter as thou didst show to the people of Sienna, such quarter will they show to thee.’ With that he caused Messer Ambrogio (somewhat confused in his mind by the blow he had received) to be conveyed into Sienna in a cart, and there he was beheaded. Before his death, he had entreated that his helmet might be restored to him, but this, his last request, was cruelly denied him. A few days afterwards there was a truce between the people of Sienna and the people of Florence, and the body of Messer Ambrogio, in full armour save the helmet, was restored to the Florentines. It was buried with great pomp in San Teodoro.”

The Italian told him that it was a recognised tradition in Tuscany, that the spirit of Ambrogio haunted that old Livornese villa: that the departed warrior was ever in search of some substitute for his lost helmet; and that, in his opinion, it had undoubtedly appeared to him. Uncle John did not mention his own conclusions; but from that time he was an altered man, and gave up Voltaire.

K.