Our Sister Republic/Chapter 16

CHAPTER XVI.

SOCIAL CONDITION AND CUSTOMS.

THERE is something curious, and—to me at least—painful, in the peculiar aspect of social life in Mexico. Though the Republic has decreed the abolition of peonage throughout Mexico, and made all men equal, at least in theory, before the law, it is powerless to break down the barriers of caste and long continued custom, which makes the woman of Mexico, though theoretically free, practically a slave. Religion has much to answer for in this; and customs as old as a race are hard to eradicate, when religion stands behind them.

The girls of the capital enjoy little of the liberty accorded to the young women of the United States, and really see but little of society until after marriage, if they are so fortunate, or unfortunate, as to ever marry at all. They are generally—I am speaking of the daughters of the wealthy or middle class families—educated in schools under the actual, though not nominal, control of the church—convents in which they were formerly educated having been abolished by law—and the system of education is not, as a rule, what we would consider liberal. They have a natural taste for music, play and sing with great ability, and often show remarkable talent for fine embroidery, wax work, drawing and painting. At home they are models of devotion to their parents, brothers, and sisters. Nowhere else on earth, have I seen such affectionate treatment of parents by children and children, by parents, as in Mexico. As a rule, the influence and control of parents over their children never fully ceases save with death, and after death their memory is cherished, it seems to me, with more fondness than elsewhere in the world.

I am proud of the daughters of my own loved land and here in this world of tropical beauty, still longed to walk once more among them, to hear the music, of their voices, and mark the air of independent self-possession which freedom gives, the bold, free step and proud grace of carriage which characterizes the haughty daughters of our conquering race. But there is one thing in which the children of Mexico far excel those of the United States, and that is, filial devotion. "Honor thy Father and thy Mother that thy days may be long upon the land which the Lord thy God giveth thee," is a command which the daughters of Mexico obey with a whole-souled earnestness that is beautiful to witness. But freedom of action outside of the family circle, there is little of any for them. An unmarried lady cannot go out upon the street alone in broad daylight; nay, she cannot even go out for a single block, in company of a gentleman, though he be the oldest friend of the family, married, and known to every man and woman on the street, according to the strict idea of social propriety in the capital. A married woman, or at least an old one, must always accompany her.

I rode out one day to Tacubuya, with a married lady friend and a young unmarried lady. Returning, we came first to the residence of the married lady, and as the carriage stopped I sprang out to help her alight; but she drew back with the remark: "But L—— is too tired to walk home, and she had better be carried there!"

"Oh yes, but it is only two blocks, and I can take her directly there in the carriage!" I remarked in my Californian simplicity.

"That will never do in Mexico!" was her prompt reply.

So I took them both to the young lady's house, left her there, and returned in the carriage with the married lady to her residence. That this incessant watching, and implied want of all confidence in the honesty and virtue of the young, is subversive of virtue, and tends to the defeat of its own object, seems to me quite clear; nevertheless, it is the custom of the country, and must be complied with by all residents in the capital. In justice to the women of Mexico let me say, that in my opinion, the custom is as unnecessary, as it is oppressive and odious in our sight.

None of the fields for independent effort and self-sustaining labor, which are open to the women of the United States, can be entered by the women of Mexico, and the future of a poor young widow, or an orphan girl with no immediate relations to care for her, may well be considered a dark and doubtful one. The natural kind-heartedness of the people, induces the most distant relatives, in such cases, to come forward to the support of the widow and the fatherless; but a life of unceasing dependence—often upon those least able to grant even that boon—is something only to be accepted as an alternative to the one thing worse.

Mexico is full of young women, naturally gifted, accomplished, and fitted to become good, loving wives and mothers, who are unmarried and have no prospect of ever being sought in marriage. Years on years of war and revolution, have forced into the army and killed off, or unfitted for marriage, a large portion of the young men of Mexico, and it is calculated that there are now in the capital, from four to seven unmarried and marriageable young ladies, to every young man of marriageable age who has any disposition to marry, or is in circumstances to justify his doing so. In the United States, a young couple may safely marry, without a dollar to begin with, for new fields of enterprise are always open, and the poor, young man of to-day may be the richest of the rich a few years hence. But not so in Mexico. As a rule—there are honorable exceptions to it—the son of a Mexican family, once rich but now impoverished, lives upon such resources, as are left to him; rides his horse on the paseo at morning and evening, pays attention to his female friends in society, and while he is idly waiting for something to turn up to better his condition, lets so much of life slip by, that he at last finds himself an old bachelor and unfit to marry. In such a condition of society, a rich, young girl will of course have no lack of suitors, but the portionless girl, though never so good, beautiful, and accomplished, has but a poor chance indeed. These truths will fall unpleasantly upon some ears, and their utterance will be resented; but they are truths, nevertheless, I am sorry to be compelled to say.

The American, or other foreigner, in good social standing, can always marry well, so far as youth, beauty, and accomplishment go, in Mexico; but the chance of his marrying into a wealthy family, and profiting by it, are not nearly so much in his favor as if he were native born. Knowing what I do of Mexico, I must say, that if I were a young American, unmarried, and "fancy free," I would prefer the wider field of enterprise open to me in the United States, to the narrower field in Mexico; but if I had been born in Mexico, I would marry among my own people, settle down, and labor with all my heart and soul for the regeneration of my country. Mexico is a country well worthy the love and self-sacrifice of all her sons.

The children in Mexico strike you with surprise and admiration. You see no idle, vicious, saucy boys running around on the streets, annoying decent people by their vile language and rude behavior. All the boys you see have earnest faces, and walk with a sedate and grave demeanor like grown up men. I never saw a badly behaved child in Mexico. In the family circle the people are models for the world. The young always treat the old with the deepest respect, and the affection displayed by parents for their children and children for their parents, is most admirable. The daughter of a good family in Mexico, though grown to womanhood, will kiss the hand of her father when she meets him on the street, and always kisses her parents, brothers, and sisters at morning and evening, and many times during the day, with the greatest warmth, and earnestness. When the children marry, they usually remain under the parental roof as long as the parents live, and the parents control the house.

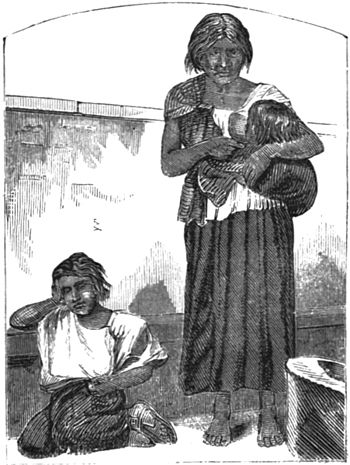

The people of Mexico are, to-day, very poor. Among the very lowest classes there is less suffering than among the class who have once been rich, and are now laboring to keep up appearances after all actual prosperity has gone, and their available resources are exhausted. Beggars lounge around everywhere, and accost you upon every street and on every block, and you can only escape their importunities while in your own house or hotel, by giving the strictest orders to your servants to exclude them. Many of these beggars are really needy, sick, maimed and helpless; but many others are graceless impostors. There is no public provision for the helpless and deserving poor, and every year the beggars increase in numbers.

TENGO NADA SEÑOR!"

The increase of late years has been very great. Only when you say "pardone!" will the street beggars bow and leave you. The numbers of horribly maimed wretches you see on the streets of Mexico is almost incredible.

The absence of anything like the bustle and noise of a northern city, is noticed at once by a stranger in Mexico. Wholesale trade there is next to none at all, and the retail stores are small, and for the most part poorly patronized. You see no drays loaded with goods for the interior, going through the streets as with us, and the cry of the auctioneer is unheard. Mexico is in no sense a commercial or manufacturing city; its productive industries hardly equaling those of a town of a tenth part of its population in the New England States. You hear the voice of the "church going bell," from morning to night, but listen in vain for the note of the steam-whistle calling operatives to their work, or the hum of busy factories, and the clanking of the laboring engine. Church towers attract the eye on all sides, but you look in vain for the factory chimney.

EARTHENWARE SELLER.

Hawkers of all kinds of goods, rebosas, and serapes, bridles, saddlery, spurs, boots and shoes, jewelry, and in fact nearly everything usually kept in a country variety store, swarm about the plaza, and under the portals, on all the principal streets. Around the market, a large portion of the country produce and garden vegetables are sold by the men and women who bring it in upon their backs, in great crates or hampers. The chicken, orange, vegetable, and earthenware venders will be readily recognized by any visitor to Mexico. The protuberance of the eyes of all these people, caused by carrying such enormous back-loads from infancy, is their most marked feature.

The citizens of the capital are supplied with water, in a great measure, by licensed water carriers, who sell the contents of a three pail jar borne on their backs, and a smaller one carried in front, all for three cents, delivering it in the house. The water carrier generally finishes his work by noon, and by 2 p. m. is blind, but quietly drunk on pulque.

A curious but effective illustration of the character of the climate of Mexico, is found in the fact that comments on the weather—the staple subject of conversation with us—are seldom heard, and do not enter into or form a part of the regular topics of the day.

WATER CARRIER.

I noticed many times during our stay in the capital, that when Mr. Seward would remark, "It is a delightful day!" or pass some other comment on the weather, the Mexicans present would respond politely in the affirmative, but with an air which plainly indicated that they were in doubt as to what was meant by the remark. One day, after a glorious ride out to Tacubuya and Chapultepec, in which I had most heartily enjoyed the pure air and warm, soft sunshine, I said to one of the younger daughters of the President, a frank-hearted, outspoken, and most amiable young lady, "This is a beautiful day! "She looked at me a moment with the old look of puzzled doubt on her face, and said, "I do not understand you!" I repeated the remark, and she then replied : "Si Señor Como no” (Yes sir; why not?") and then went on to say that all the days were beautiful as a general thing; only now and then a norther making it otherwise. The fact is, that the weather is so generally beautiful, and the exceptions so rare, that the words we use so often every week in our changeable climate, have no appreciable meaning to the dwellers in this favored clime.

ORANGE SELLER.

The belief in the "evil eye," a superstition of purely Eastern origin, is quite common among the lower classes of the Mexican people. Many times I have seen a poor Mexican mother standing by the roadside, with her young infant in her arms, and on observing one of our party looking towards her, draw the end of her rebosa quickly over the face of the child, lest its fortunes should be blighted and its soul imperiled by the glance of the stranger. The superstition is confined solely to the lower class of the people, but it manifests itself exactly as it does in Arabia and the Barbary States to this day, and evidently came to America with the Spaniards.

It is customary in all Spanish American countries to offer a guest everything which he may require for his. comfort and convenience, and literally, to put the entire house, and every thing in it, at his disposal for the time being. This practice grows out of a genuine feeling of liberality, and hospitality, but the language used is such as to be quite readily misunderstood by a stranger who measures expressions by the cold matter-of-fact rule in use in colder countries, and attaches more weight to a mere formality than it is justly entitled to. When you enter the house of a friend, or even a person to whom you have a letter of introduction, in Spanish America, he at once tells you, that you are "in your own house," and that you are the master and he your guest, or something to that effect. He really expects you to make yourself at home in the broadest sense of the term, but on the other hand, pays you the compliment of supposing that you have, at least, an ordinary amount of common sense, and will know enough of what constitutes the rules and customs of society, not to abuse, the offer, and outstay your welcome.

POULTRY SELLER.

If you particularly admire any picture, or article of jewelry or furniture, he will immediately tell you that it is at your disposal, and you are quite welcome to carry it away with you. He does not, in all probability, expect you to accept the offer; but if you are ignorant or ill-bred enough to do so, he will conceal his chagrin, if he feels any, and permit you to carry away anything you fancy, however inconvenient it may be for him to part with it.

Sometimes ludicrous, and even painful results follow this misapprehension of the true value of courteous expressions made by a host or hostess to a guest. I remember a case of an English lady who was on a visit to Mexico, and on making the acquaintance of a family of wealth and position, was one day offered a beautiful and valuable set of diamonds and emeralds, which had been in the family for generations. She was told, of course, that she was welcome to take them away with her, and in the innocence of her heart did so.

VEGETABLE SELLER.

The result was, that mutual friends learning the true state of the case, were compelled to go to her and explain how matters stood, much to her mortification. She at once returned the jewels with an explanation that they had proved, on trial, not to suit her complexion and style of dress, and offering in return for the courtesy shown her, to send a set of her own jewelry to the house, as a present to one of the daughters of the family. Of course her offer was declined, with many thanks, and renewed offers of service from the other side. Good common sense in this case, made up for the lack of familiarity with the social customs of the country, but I have known some of my own countrymen and countrywomen who were less fortunate.

For years, the residents of San Francisco were familiar with the face and form of an eccentric, and probably mildly insane old individual, who delighted in the sobriquet of Uncle Freddy, alias Washington the Second. What his real name was I never knew, but he was an Englishman by birth, I believe, and while he imagined, or affected to imagine himself the very counterpart of Washington, he really did resemble the portraits of Benjamin Franklin, in a remarkable degree.

Uncle Freddy could be seen parading Montgomery street any fine day, dressed in a full buckskin suit and cocked hat, regular "old Continental" style, or black velvet, similarly cut, and with knee-breeches, white stockings, and silver buckled shoes. Sometimes he carried a gorgeous banner, the legends on which commemorated his deeds of valor and humanity, and his claims upon the public crib as a benefactor of our country and race. Any contribution in acknowledgment of his eminent services was welcome, and the larger the donation the more profuse were his apologies and protestations of gratitude.

The sun of fortune seemed to shine lovingly upon Uncle Freddy, but he had a weakness like all other great men, and in an evil moment it proved his ruin. He imagined himself a woman-killer, and would indulge in the most ludicrous demonstrations of politeness towards every body on the street whose attention was drawn to his slightly obese figure, set off by the curiously antiquated costume which he affected.

San Francisco has still another speciality, in the shape of "Norton I, By the Grace of God and the Will of the people, Emperor of the United States, Protector of Mexico, and Sovereign Lord of the Guano Islands," as he styles himself in all his proclamations. You may see him to-day, dressed in a soiled and greasy uniform, cocked hat and feather, carrying a heavy cavalry sword and a huge knotty cane up and down Montgomery street, or peering curiously into the shop windows, examining every work of art, with a critical and appreciative eye.

The cares of state weigh heavily upon Norton the First, and in his advanced age he is becoming subject to certain slight ebulitions of wrath, on the slightest provocation. He daily sends off communications to the different crowned heads of Europe and Asia, commanding them to do this thing or that thing, immediately. His telegraphic dispatches would—and generally do—fill an ordinary waste-basket every week in the year, and the number of proclamations which he sends to the different newspaper offices, with command to publish at once, on penalty of instant death and confiscation of property, is beyond computation. He was a wealthy speculator in breadstuff's, in the early days of San Francisco, and probably receives more or less assistance from his old and more fortunate acquaintances, and possibly also, from a secret order of which he was once a member; but the full secret of his living and maintaining his royal state, is a mystery to most people. When Maximilian arrived in Mexico, he received communication after communication from the Emperor Norton I., signed by His Majesty in person, and adorned with seals of the size of a small cheese, giving him much good advice, and offering many suggestions as to the method of conducting the affairs of the new Empire, which it was evidently supposed would receive due consideration, as coming from an old hand and successful operator in the business of Imperialism. These documents received much attention at first, and for a long time bothered the head of the son of the House of Hapsburg-Lorraine, and all his ministers, exceedingly.

One day, Uncle Freddy mentioned to a friend, in confidence, that he had written to Queen Victoria on some subject, and the treacherous friend at once related the circumstance to the Emperor, adding that he—Uncle Freddy—had denounced the Emperor as a humbug and a swindle. From that moment the Emperor Norton First, and Washington the Second, were mortal enemies, and every day added fuel to the flame of their animosity.

Washington opened a curiosity shop on Clay street, and the Emperor went up there and smashed it, and all its contents, into a cocked-hat. Washington appealed to the police, and was told, that the Emperor being the source of all power, no writ would hold against him. Then Washington met a Chinese woman of the better class on the street, gorgeously arrayed, and as she looked at him with curiosity, bowed to her. This incident was reported to the Emperor, with the addition that the young female Mongolion was a Chinese princess, sent over to America to be married to His Majesty, in order to bring about an alliance offensive and defensive between the two Empires, and that Uncle Freddy was endeavoring to get her prejudiced against royalty, and in favor of himself.

This last straw broke the Imperial Camel's back, and Norton the First, at once issued a peremptory order to General McDowell, for the arrest and execution of Uncle Freddy, adding, that if the order was disregarded as others had been, he would go out, sword in hand, and put down the rebellion summarily. The wags who had been carrying on the joke, seeing that matters had come to a dangerous pass, and bloodshed was not unlikely to follow, consulted together, and determined to induce Uncle Freddy to emigrate, at once, to New York. On the way down the coast, the steamer on which Uncle Freddy was a passenger, touched at Acapulco, and the venerable representative of the Father of His Country, asked Señor Mancillas, now of the Mexican Congress, who was also a passenger, to introduce him to General Juan Alvarez, then in command of the port of Acapulco, and Governor of the State of Guerrero. Mancillas thoughtlessly complied, and the old fellow at once made himself extremely familiar with the authorities on shore.

When the time for the steamer to depart arrived, Mancillas went to pay his respects and bid good-bye to General Alvarez, and was not a little surprised to find Uncle Freddy installed in the house in all the pomp of the Father of His Country, indeed, and a guest of national importance. He had informed the gallant old Republican General, that he had rendered distinguished service to Mexico during the war of 1846-7, which he had opposed with all his might, and final success. The General of course told him that he was welcome to the country, and that the house and everything in the house was his own. If he could make up his mind to spend the remainder of his days in so poor a country as Mexico, and so poor a city as Acapulco, he would feel only too happy, to have him for a guest for the rest of his life.

Uncle Freddy took a look at the premises, rather liked the way everything was arranged and proceeded to dine sumptuously. When Señor Mancillas, at his last call, reminded him that the steamer's gun had been fired, and it was time to go off in the boat, he stretched his legs comfortably in the cool verandah, and informed him that he had determined to accept the hospitable invitation which had been extended to him, make that his home, and consider himself the guest of General Alvarez and the Mexican Republic, for the remainder of his days. Mancillas argued and expostulated in vain; Uncle Freddy had struck too good a thing, and he meant to enjoy it.

At last, in a fit of very desperation, Mancillas sent a party to invite the healthy old shade of the father of his country outside the door, and then seize him, and hurry him down to the boat and off to the steamer by main strength.

When General Alvarez heard of the "outrage" he was in a great passion, and could only be appeased by hearing the whole story, and learning that the kidnaping had been done by the order of Señor Mancillas, in order to relieve him—the General—of the presence of a lunatic, whom he had thoughtlessly introduced into the house, and who proposed to take the General at his word, and stay there for life.

Uncle Freddy was borne away from the shores of Mexico sorely against his will, and when last seen, on Broadway, New York, was still bitterly bewailing the lost opportunity, like the man who being asked to "excuse" a lady to whom he had popped the question, excused her, and as he informed his friends, regretted having done so, to the end of his existence.

Many strangers are inclined to look upon the profuse offers of hospitality on the part of the Spanish American people, as utterly insincere, and made with an expectation in advance that they would never be accepted. This view of the case is, however, far too broad and sweeping. As a rule, the people of Mexico are truly hospitable in the broadest acceptation of the term, and strangers are welcomed and entertained with pleasure; but it is, of course, expected that they will use reason, and show some sense of delicacy; and a mere arbitrary translation of the expressions used would be unjust, as putting language into the mouth of the host or hostess which they never intended to use.

It is quite the fashion for foreigners of all classes, to denounce the Mexicans as a set of thieves and scoundrels, false, treacherous, cowardly, unreliable, and without a single redeeming characteristic. I will not claim for the Mexicans that they are a nation of angels and saints; they have their virtues and their faults like all other nations. But that they are more dishonest, or more given to disgraceful peculation and swindling than many of the foreigners with whom they have had to deal, I cannot believe. There are some most notable exceptions among the foreign-born residents of Mexico, but it is nevertheless the fact, that far too many of them bore but an indifferent character in their own country, came to Mexico to get rich "by hook or by crook," and have no scruples worth mentioning as to how they make the money so that they make it and get away with it. I have heard a thousand stories illustrative of the practices of foreigners of this class in Mexico; a couple will be sufficient to convey a fair idea of the conduct of those who are accustomed to denounce the Mexicans, in the most unmeasured terms, for alleged dishonesty and unreliability.

During the French intervention, a large European importing house, doing business in Western Mexico, landed a large invoice of goods at Manzanillo, which port was then in possession of the Republicans. The city to which they desired to send the goods for sale, was in the possession of the Imperialists, and they must deal with both parties in order to have them passed through the lines of the opposing forces. They accordingly proposed to the Republican authorities to pay the duties, contingently. As they represented that, the Imperialists would in all probability let the goods go through, but there was no certainty of their doing so, they proposed to give the Republic drafts on themselves, payable on the receipt of the acknowledgment that they had been passed. The Republicans being sorely in want of funds consented, and gave receipts to be exhibited to the Imperialists as evidence that the goods had already paid duty.

The goods went through all right, and were disposed of at swinging profits within the Imperialist lines, the Imperialist collector being convinced that a heavy duty had already been paid, and that it would be wrong to exact a second under the circumstances. Then, when the drafts were presented for payment, the drawers replied: "Oh! but you are not representative of the Government of Mexico! The Governments of Europe have acknowledged the Empire as the only legitimate Government in Mexico, and it will be necessary for you to have these drafts presented by the imperial authorities; we cannot recognize them in any other hands." The Mexican authorities were fairly outwitted, and both parties swindled out of the entire duties.

A friend of the house which perpetrated this neat little piece of thieving—for it is nothing less—told the story to me as an illustration of the shrewdness and business ability of the head of the concern, and really seemed to think it a very creditable transaction on the part of the importers, who pocketed a small fortune by the operation.

Another transaction, the parties to which were men occupying prominent positions in politics, took place at the City of Mexico. A revolutionary party was driven out of the capital by the legitimate authorities. As they—the revolutionists—were hurrying away, a gentleman of wealth, who was complicated and found it necessary or desirable to leave with them, in order to save his magnificent private residence from occupation and confiscation by the Government, made a lease of it at a nominal rent to the French minister, who immediately took possession. The owner soon made his peace with the Government, and according to the previous arrangement returned and demanded the restoration of his property. He was put off and refused on one pretext or another, until a new French minister came out to replace the first, and the property was then turned over to him, against the indignant and emphatic protest of the hapless owner. The new minister held the property until turned out of it by a decision of the last court of appeal, and then, when the owner was restored to the possession, he found that every article of furniture, all the rich and costly plate, etc., etc., was gone, and that in fact, only the four walls of the once magnificently furnished house remained. The plate was taken to the United States, and a part of it, at least, was sold at auction at Washington, and is now in the possession of a friend of mine who purchased it in good faith, little dreaming that men so high in office and authority could be guilty of having stolen it outright.

I suppress the names and dates for obvious reasons, in both cases, but the facts, especially in regard to the last transaction, are so well known in Mexico that any person can verify them who cares to do so. Such transactions are bad enough in all conscience, but they are not worthy of being mentioned in connection with such frauds as the "Jecker Claim," which was backed up—cooked up I ought to say perhaps—by the minister of a first-class European power, and in the hands of a cunning imperial schemer, served as one of the principal pretexts for the invasion of Mexico, and the attempt to establish a hostile Empire on our borders.

I ought to say on behalf of the women of Mexico, that all foreigners, even those who denounce the men in the most unjust and unmeasured terms, unite in praising their constancy, faithfulness and devotion. They are not only as wives and mothers devoted to their husbands and children, but they are ever ready to assist in every possible manner, the afflicted. The suffering of every nationality, even those who have come among them as enemies, always find them ready to sympathize, aid, and comfort to the utmost of their ability. From highest to lowest this is the rule. You have only to tell a Mexican woman that your life is in danger and that you throw yourself upon her protection, and you may be sure that she will risk her own life, honor, everything in fact, to protect you.

In this fact is found the ready explanation of the escape of so many revolutionists after their defeat by the Government. The most detested wretch on the earth can appeal to the women of Mexico for food and shelter, and it will be given him. To refuse either, would be in the eyes of a Mexican woman, an unpardonable sin against God and humanity, and thus it is that men like Marguez, who have committed murders and other crimes without number, almost invariably escape justice, and succeed in reaching a foreign shore. A prisoner sentenced for a long term, applied to me to say a good word for him to the authorities, and a Mexican lady, who accompanied me at the moment, urged me to comply.

"But he is a rascal and an enemy of your family!" I said.

"Oh Señor, that is true, but he is sick and in prison, pobrecito!" was the only reply.

She is a better Christian than I.

The Mexican servants in the City of Mexico are a peculiar class. They earn but a fraction of what we in the United States would call a salary—say from three to fifteen dollars per month, five or six dollars being a fair average. They often remain several years in a family, and many of them, in fact, are born, raised, and die in the same house, and in the family of their first master. With foreigners, they are generally a little less reliable than when serving native masters, probably, because they are less closely watched, and their employers, being less familiar with their habits and peculiarities, are less able to protect themselves from their eccentricities. They will generally leave a very valuable article or large sum of money untouched, but small articles of finery and small coins are very likely to get lost, if left around loose in their reach.

With us, it is the custom to pay the largest salaries to those of our employes who have the responsibility of handling the most money, but a lady in Mexico told me with charming naivette, that the rule was just the contrary there, as those who handled the most money had the least need of a salary. It is so common a thing for the cook or purveyor for a family to make a small percentage off the purchases, that it is looked upon as quite a matter of course, and nothing is thought of it.

One day Mr. Fitch, in passing along the street in Mexico, saw a pair of patent-leather gaiters, which being highly ornamented, pleased his fancy, and he forthwith ordered a pair built to fit him. When the servant brought them home, I asked him how much they cost. He answered promptly:

"Five dollars and a half!"

I said—as I could with impunity, since Mr. Fitch did not understand Spanish:

"You ought to add fifty cents for yourself!"

"I have done so, Señor!" said the fellow promptly, smiling knowingly, as if he understood the situation at once.

But you should have added a dollar instead of fifty cents; the padre is delighted with the boots and would stand it!"

The fellow, without a moment's hesitation, turned to Mr. Fitch and told him the bill was six dollars. The money was paid, and as he received it and turned to go, he dropped five dollars into his pantaloons pocket, and transferred one-half-dollar of the balance to his jacket pocket, and with the most amiable and knowing air imaginable, held the other fifty cent piece out in his open hand for me to take, as he passed me in the doorway. He meant to do business on the square, and come to a fair divide. From what I had said, he took me for the financial man of the party, and supposed, of course, that I was—pardon the Californianism—"on the make" as well as himself. My natural and unconquerable modesty, coupled with the fact that I wore a uniform which I felt bound to honor while in a foreign land, induced me to refuse the money, and whisper to him to keep it as a present. He kept it!

The servants furnished to Mr. Seward's party by the Mexican Government during our stay in Mexico, certainly would compare favorably with any I have ever seen, being attentive and efficient, and at least, as honest as they will average anywhere. From one side of the continent to the other, our clothing and other articles of baggage were at their mercy, and we lost nothing whatever. In fact, we found it impossible to lose some things which we would gladly have left behind us.

At one point on our journey, some inconsiderate friend presented Mr. Seward with a huge petrifaction from some stone quarry. This proved a perfect fossil elephant, and after the shins of the entire party had suffered fearfully, it was left behind us—by accident of course—at Puebla. The next day we were congratulating ourselves on the loss, when Pedro, one of the servants who had accompanied us across the continent, came smiling up to the coach door, with the monstrosity carefully done up in a rag—he had carried it this way the entire distance, and was proudly conscious of having, in so doing, deserved well of his country and mankind in general. He was duly thanked, of course, and we kicked it about from one side of the coach to the other, with many a secret blessing on the donor and the faithful servant who had returned it.

At Palmar, I placed it under my bed, and congratulated myself on having seen the last of it, as the coach rolled away next morning. Vain delusion! At Orizaba, next day, I went into the dilligence office to transact some business, when the agent said to me:

"Señor, you lost something at Palmar, but give yourself no uneasiness; it will be down here to night by the dilligence. They are honest people and would not take anything from you."

"Was it money that they found?" I asked, affecting a carelessness I was far from feeling.

"O no, Señor: a big rock; very curious indeed, and doubtless very valuable."

My heart was too full for words, and I could only bow my thanks and shake his hand in silence.

On leaving Orizaba I tried it on and failed more ignobly, for it was picked up and placed upon my hatbox, which it smashed down at once; and so in spite of every effort I could make, it clung to me like the nightmare, and turned up in due time at Vera Cruz.

But in that ancient city I was master of the situation. I occupied a room at a hotel, pending the arrival of Mr. Seward from Orizaba,—having gone down to the coast in advance of the remainder of the party from that point—and had no one to watch my actions, with a view of doing me a service on every occasion in spite of myself. I took it one night, carefully wrapped up in paper, and carrying it down to the city front, climbed upon some railroad material and hurled it over the wall into the shallow water outside.

I got back to the hotel unobserved, but going down to the mole next day, I observed a party of fishermen and idlers gathered about something which they had picked up and brought there in a boat; it was that accursed petrifaction again. I bought it from the happy finder for twenty-five cents, and carried it to where some men were overhauling a lot of goods in boxes. From them I borrowed a hatchet, and pretending to be deeply curious as to what was inside, proceeded with the wise look of a regular "rock-sharp," to smash it into a thousand pieces. I found no gold inside it, and in well simulated disappointment gathered up the pieces, and threw them, one after another, as far as I could send them, out into the deep water, taking good care that no two pieces, of any size, fell near together. I have not seen any of it since, thank Heaven!

The men servants are generally better posted than the female servants in the matter of foreigners. One female servant in the family of a friend who was going to the United States on a visit, was horrified at the thought of the fate that awaited her beloved mistress.

"Oh Señora for the love of God and the holy saints, don't go among those Yankees! They will eat you; they will certainly eat you!" was her constant cry when she saw the final preparations for departure being made. They left her in tears and despair, fully convinced that her dear mistress would be devoured as soon as she put her foot on American soil. She told her mistress that when the army of Gen. Scott entered Mexico, she fled to the mountains with her husband, and staid there until they left the country. They never talk back, after the manner of the Italian servants in America, but reply to every epithet with a fresh offer of service.

"You d—d drunken loafer!" thundered a master to his servant who was endeavoring to back an unusually heavy load of pulque.

"Si Señor, at your service!" was the polite and prompt reply, as the mozo lifted his hat and bowed like an India rubber man.

It takes about four servants in Mexico, to do the work of one in the United States, and as you board them, the cost of labor for a family is considerable, after all. If you pay a servant his or her wages in advance, or day by day, the chances are, that you can keep them almost any length of time; but let them get a few dollars due them, and they are almost certain to come to you, and say:

"Please Señor or Señora, I want to have my wages settled up on Saturday, as I am going to the village where my family reside, to rest a few weeks. When I have had a good rest I will come back if you want me!"

The idea of allowing money to accumulate on their hands is exceedingly against their fancy, and they make it a point to get rid of it as soon as they lay their hands upon it. I thought before this trip, that servants in the United States were the worst in the world, but heard just as much complaint about them in Mexico as in California. In all fairness I must say, that I think the Mexican servant system better, or at least, less troublesome than ours.

The census takers in the United States sometimes complain of the annoyances and indignities which they are made to suffer; but they have a glorious time compared with their fellow-laborers in Mexico. It is said that the actual population of the country can only be approximated, it being impossible to get at the number of able-bodied men in any given town. The intelligent and educated families will answer at all times, correctly; but among the lower classes from which the army is mainly recruited, it is next to impossible to get correct returns. The appearance of a man with a book, or roll of paper and pencil, is the signal for all the men capable of doing military duty to skedaddle in double-quick time, and the women, fearing that it is a preliminary arrangement for a conscription, persistently declare that there is not an able-bodied man on the premises.