of the arpeggio to fall upon the beat, as for instance in Mendelssohn's 'Lieder ohne Worte,' Book v. No. 1, where the same note often serves as the last note of an arpeggio and at the same time as an essential note of the melody, and on that account will not bear the delay which would arise if the arpeggio were played according to rule. (See Ex. 11, which could scarcely be played as in Ex. 12).

![{ \time 2/4 \key a \major \tempo "11." << {

<< \relative a'' { a8 gis fis e | cis' a gis fis \bar "||" }

\\

\relative b' { r8 \grace { b32[ d e] } gis8 r \grace { gis,32[ b d] } e8 |

r \grace { cis16[ e] } a8 r \grace { a,16[ cis] } fis8 } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key a \major \relative e

{ <e e,>8 \clef treble r8 \grace { d'32[ e gis] } b8 r \clef bass |

<e,, e,>8 \clef treble r8 \grace { cis'32[ e a] } cis 8 r \clef bass | } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/n/qnd8qtvf84x5ktrlqbnwznrze94tyo9/qnd8qtvf.png)

![{ \time 2/4 \key a \major \tempo "12." << {

<< \relative a'' { a8 ~ a32 gis16. fis8 ~ fis32 e16. | cis'8 ~ cis32 a16. gis8 ~ gis32 fis16. \bar "||" }

\\

\relative b' { r8 \times 2/3 { b64[ d e] } gis16. r8 \times 2/3 { gis,64[ b d] } e16. | r8 cis64[ e] a16. r8 a,64[ cis] fis16. } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key a \major \relative e

{ <e e,>8 \clef treble r8 \times 2/3 { d'64[ e gis] } b16 r32 r8 \clef bass | <e,, e,>8 \clef treble r8 \times 2/3 { cis'64[ e a] } cis16 r32 r8 | } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/6/u/6uypx3pcpcpdb0a27ruityhyk46flgo/6uypx3pc.png)

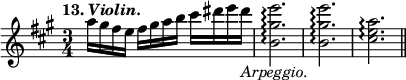

In music of the time of Bach a sequence of chords is sometimes met with bearing the word 'arpeggio'; in this case the order of breaking the chord, and even the number of times the same chord may be broken, is left to the taste of the performer, as in Bach's 'Sonata for Pianoforte and Violin,' No. 2 (Ex. 13), which is usually played as in Ex. 14.

![{ \time 3/4 \key a \major \tempo "14." \relative b' { \override TupletBracket #'bracket-visibility = ##f \override TupletNumber #'stencil = ##f \times 2/3 { b16([ gis' e'] e[ gis, b,)] b16([ gis' e'] e[ gis, b,)] b16([ gis' e'] e[ gis, b,)] } } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/p/q/pqwnzuawxwoq2w21kgg07epx354ch6z/pqwnzuaw.png)

Sometimes the arpeggio of the first chord of a sequence is written out in full, as an indication to the player of the rate of movement to be applied to the whole passage. This is the case in Bach's 'Fantasia Cromatica,' (Ex. 15), which is intended to be played as in Ex. 16. Such indications however need not always be strictly followed, and indeed Mendelssohn, speaking of the passage quoted, says in a letter to his sister: 'I take the liberty to play them (the arpeggios) with every possible crescendo and piano and ff., with pedal as a matter of course, and the bass notes doubled as well. … N.B. Each chord is broken twice, and later on only once, as it happens.' (Mendelssohn, 'Briefe,' ii. p. 241). In the same letter he gives as an illustration the passage as in Ex. 17.

![\new ChoirStaff << \new Staff = "up" { \key f \major \tempo "15." \override TupletBracket #'bracket-visibility = ##f \change Staff = "down" \times 2/3 { d16[ f a] } \times 2/3 { d' \change Staff = "up" f'[ a'] } \times 2/3 { d''[ a' f'] } \change Staff = "down" \times 2/3 { d'[ a f] } \change Staff = "up" <e' g' bes' e''>2 | << { <f'' d''>2 <fis'' ees'' c''> \bar "||" } \\ { <f' a'>2 a' } >> }

\new Staff = "down" { \clef bass \key f \major s2 <cis' g e d>_\markup { \italic "Arpeggio legato." } | << { <d' a> <c' a> | } \\ { <f d> <fis d> } >> } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/4/h/4hy2t7qkk985pyhgh22vmzpzqaje51r/4hy2t7qk.png)

![\new ChoirStaff << \new Staff = "up" { \key f \major \tempo "16." \override TupletBracket #'bracket-visibility = ##f \change Staff = "down" \times 2/3 { d16[ f a] } \times 2/3 { d' \change Staff = "up" f'[ a'] } \times 2/3 { d''[ a' f'] } \change Staff = "down" \times 2/3 { d'[ a f] } \times 2/3 { d[ e g] } cis'32 \change Staff = "up" e'[ g' bes'] e''[ bes' g' e'] \change Staff = "down" \times 2/3 { cis'16[ g e]^\markup { \raise #3 \smaller etc. } } \bar "||" }

\new Staff = "down" { \clef bass \key f \major s1 } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/f/y/fylnrrbut7rd79179dnh3nmlul9ag7z/fylnrrbu.png)

![\new ChoirStaff << \new Staff = "up" { \key f \major \tempo "17." \cadenzaOn \change Staff = "down" d,32[^\markup { \italic Ped. } d f a] \change Staff = "up" d'[ f' a' d'' a' f' d' \change Staff = "down" a f d] d,[ d f a] \change Staff = "up" d'[ f' a' d'' a' f' d' \change Staff = "down" a f d] d,[^\cresc d\! e g cis'] \change Staff = "up" \repeat percent 2 { e'[ g' bes' e'' bes' g' e' \change Staff = "down" bes g e] } \bar "||" }

\new Staff = "down" { \clef bass \key f \major \cadenzaOn s1. } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/j/bj5ww0cj2oqpq7cwoa0hjtr7khz2ozp/bj5ww0cj.png)

When an appoggiatura is applied to an arpeggio chord, it takes its place as one of the notes of the arpeggio, and occasions a delay of the particular note to which it belongs equal to the time required for its performance, whether it be long or short (Ex. 18).

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f << { \tempo "18." \relative c'' { \cadenzaOn \acciaccatura d8 <c g e>4\arpeggio \bar "|" \appoggiatura d8 < c g e>4\arpeggio \bar "|" \appoggiatura f,4 <c' g e>2\arpeggio \bar "||" } }

\new Staff { \relative e' { \cadenzaOn \set tieWaitForNote = ##t \times 2/3 { e16[ ~ g ~ d'] } <c g e>8 | << { s32 d16.->( c8) } \\ { \set tieWaitForNote = ##t \stemUp e,64[ ~ g] ~ \stemDown <g e>8.. } >> | f32([ g ~ c8.] ~ <c g e>4) | } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/2/k23zmqe08q79igb74jk56ihxldqa5cx/k23zmqe0.png)

Chords are occasionally met with (especially in Haydn's pianoforte sonatas) which are partly arpeggio, one hand having to spread the chord