the same number of bars and therefore of accents.

[ E. P. ]

ACCENTS. Certain intonations of the voice used in reciting various portions of the liturgical services of the Church. The Ecclesiastical Accent is the simplest portion of the ancient Plainsong. Accents or marks, sometimes called pneums, for the regulation of recitation and singing were in use among the ancient Greeks and Hebrews, and are still used in the synagogues of the Jews. They are the earliest forms of notes used in the Christian Church, and it was not till the 11th and 12th centuries that they began to be superseded by the more definite notation first invented by Guido Aretino, a Benedictine monk of Pomposa in Tuscany, about 1028. Accents may be regarded as the reduction, under musical laws, of the ordinary accents of spoken language, for the avoidance of confusion and cacophony in the union of many voices; as also for the better hearing of any single voice, either in the open air, or in buildings too large to be easily filled by any one person reciting in the perpetually changing tones of ordinary speech. They may also be considered as the impersonal utterance of the language of corporate authority, as distinguished from the oratorical emphasis of individual elocution.

Precise directions are given, in the ritual books of the Church, as to the accents to be used in the various portions of the sacred offices and liturgy. Thus the Prayer Accent or Cantus Collectarum is either Ferial—an uninterrupted monotone, or Festal—a monotone with an occasional change of note as at (a), styled the punctum principale, and at (b) called the semipunctum. The following examples are taken from Guidetti's 'Directorium Chori,' compiled in the 16th century under the direction of Palestrina (ed. 1624); the English version is from Marbeck.

1. The Ordinary Week-day Accent for Prayers ('Tonus orationum ferialis').[1]

2. The following Ferial Accent (Tonus ferialis) is used at the end of certain prayers.

3. The Festival Accents for Prayers ('Tonus orationum festivus').

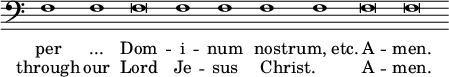

4. In the ancient Sarum use there was the fall of a perfect fifth, called the grave accent, at the close of a prayer, with a modification of the Amen, thus—:

5. There are also the accents for reciting the Holy Scriptures, viz. the Cantus or Tonus lectionis, or ordinary reading chant; the Tonus Capituli for the office lessons; the Cantus Prophetarum or Prophetiae, for reading the Prophets or other books not Gospels or Epistles; the Cantus Epistolae and Evangelii for the Epistles and Gospels; as well as other accents for special verses and responses, of great variety and beauty, which may be best learnt from the noted service-books themselves. The following examples will show their general character. The responses are for the most part sung in unison but some of them have been harmonised for several centuries, and such as are most known in the English Church are generally sung with vocal, and sometimes with organ harmonies. These harmonies have, however, in too many cases, obscured the accents themselves, and destroyed their essential characteristics. In Tallis's well-known 'Responses' the accents being given to the tenor are, in actual use, entirely lost in the accompanying treble.[2]

(a) The Tonus Lectionis.

(b) Tonus Capituli. Monotonic except at the close.

- ↑ The breves and semibreves in the above examples represent the old black notes of the same name (

and

and  ) which answered to the long and short times of syllables in prosody (– and ˇ): a more prolonged sound was indicated by the long (thus

) which answered to the long and short times of syllables in prosody (– and ˇ): a more prolonged sound was indicated by the long (thus  or

or  ).

).

- ↑ For a rearrangement of these, with a view to restore the proper supremacy of the accents themselves, see Appendix 1 to 'Accompanying Harmonies to the Rev. Halmore's Brief Directory of Plainsong'; and for the rule of their proper formation, see the 'S. Mark's Chant Book,' p. 61.