before the first or above the second of two similar notes, indicated that the second of the two was to be 'altered,' i.e. doubled in length, again for the sake of preserving the triple rhythin; for example—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

In the absence of the dot in the above example, there would be a doubt as to whether the two breves ought not to be rendered imperfect by means of their respective semibreves, as in Ex. 1. Like the point of perfection therefore this dot preserves the first note from imperfection; but owing to the fact that it is followed by two short notes (instead of three as in Ex. 4), it also indicates the 'alteration' or doubling of the second of the two.

The third kind of dot, the 'point of division,' answers to the modern bar, but instead of being used at regular intervals throughout the composition, it was only employed in cases of doubt; for example, it would be properly introduced after the second note of Ex. 1, to divide the passage into two measures of three beats each, and to show that the two breves were to be made imperfect by means of the two semibreves, which latter would become joined to them as third and first beats respectively, thus—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Without the point of division the example might be mistaken for the 'alteration ' shown in Ex. 5.

The last of the four kinds of dots mentioned above, the 'point of addition,' was identical with our modern dot, inasmuch as it added one half to the value of the note after which it was placed. It is of somewhat later date than the others (about A. D. 1400), and belongs to the introduction of the so-called tempus imperfectum, in which the rhythm was duple instead of triple. It was applied to a note which by its position would be imperfect, and by adding one half to its value rendered it perfect, thus exercising a power similar to that of the 'point of perfection.'

[App. p.618 "Handel and Bach, and other composers of the early part of the 18th century, were accustomed to use a convention which often misleads modern students. In 6-8 or 12-8 time, where groups of dotted quavers followed by semiquavers occur in combination with triplets, they are to be regarded as equivalent to crotchets and quavers. Thus the passage

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

is played

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

not with the semiquaver sounded after the third note of the triplet, as it would be if the phrase occurred in more modern music."]

In modern music the dot is frequently met with doubled; the effect of a double dot is to lengthen the note by three-fourths, a minim with double dot

being equal to seven quavers, a doubly dotted crotchet

to seven semiquavers, and so on. The double dot was the invention of Leopold Mozart, who introduced it with the view of regulating the rhythm of certain adagio movements, in which it was at that time customary to prolong a dotted note slightly, for the sake of effect. Leopold Mozart disapproved of the vagueness of this method, and therefore wrote in his 'Violinschule' (2nd edition, Augsburg, 1769), 'It would be well if this prolongation of the dot were to be made very definite and exact; I for my part have often made it so, and have expressed my intention by means of two dots, with a proportional shortening of the next following note.' His son, Wolfgang Mozart, not only made frequent use of the double dot invented by his father, but in at least one instance, namely at the beginning of the symphony in D written for Hafner, employed a triple dot, adding seven eighths to the value of the note which preceded it. The triple dot is also employed by Mendelssohn in the Overture to Camacho's wedding, bar 2, but has never come into general use.

Dots following rests lengthen them to the same extent as when applied to notes.

In old music a dot was sometimes placed at the beginning of a bar, having reference to the last note of the preceding bar (Ex. 7); this method of writing was not convenient, as the dot might easily escape notice, and it is now superseded by the use of the bind in similar cases (Ex. 8).

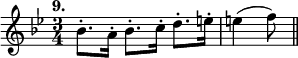

When a passage consists of alternate dotted notes and short notes, and is marked staccato, the dot is treated as a rest, and the longer notes are thus made less staccato than the shorter ones. Thus Ex. 9 (from the third movement of Beethoven's Sonata, Op. 22) should be played as in Ex. 10, and not as in Ex. 11.

![{ \time 3/4 \key bes \major \tempo "10." \relative b' { \stemDown bes8[ r16 a-.] bes8[ r16 c-.] d8[ r16 e-.] \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/1/g/1gztbisfud6uw1a4073il0tllj13uhr/1gztbisf.png)

![{ \time 3/4 \key bes \major \tempo "11." \relative b' { \stemDown bes16-.[ r r a-.] bes-.[ r r c-.] d-.[ r r e-.] \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/7/a/7a5pz0jnaowrzmus4gnt2zutgc6fx7y/7a5pz0jn.png)

In all other cases the value of the dotted note should be scrupulously observed, except in the opinion of some teachers—in the case of a dotted note followed by a group of short notes in moderate tempo; here it is sometimes considered allowable to increase the length of the dotted note and to shorten the others in proportion, for the sake of effect. (See Koch, 'Musikalisches Lexicon,' art. Punkt; Lichtenthal, 'Dizionario della Musica,'art. Punto.) Thus Ex. 12 would be rendered as in Ex. 13.