DUDDYNGTON, Anthony, citizen of London, contracted in 1519 to build an organ for All-Hallows, Barking, for the sum of £50.

[ V. de P. ]

DUET (It. Duetto; Fr. Duo). A composition for two voices or instruments, either with or without accompaniments. Some writers use the form 'Duet' for vocal, and 'Duo' for instrumental compositions; this distinction, however, is by no means universally adopted. Strictly speaking, a duet differs from a two-part song in the fact that while in the latter the second voice is mostly a mere accompaniment to the first, in the duet both parts are of equal importance. In cases where it is accompanied, the accompaniment should always be subordinate to the principal parts. The most important form of the duet is the 'Chamber Duet,' of which the old German and Italian masters have left many excellent examples (see especially Handel's Chamber Duets'). These duets were often in several movements, sometimes connected by recitatives, and almost invariably in the polyphonic style. The dramatic duet, as we find it in the modern opera, is entirely unrestricted as to form, which depends upon the exigences of the situation. Among the finest examples of operatic duets may be named those in the first act of 'Guillaume Tell,' in the fourth act of 'Les Huguenots,' and in the second act of 'Masaniello,' in the more modern school; while the duets in 'Fidelio' and in the operas of Mozart and Weber are models of the older classical forms of the movement. Many of the songs in Bach's cantatas in which the voice and the obligato instrument are equally prominent are really duets in character, but the term is not applied to the combination of a voice and an instrument. The word is now often employed for a pianoforte piece à quatre mains, of which Schubert's 'Grand duo' (op. 140) is a splendid example.

[ E. P. ]

DUETTINO (Ital. dimin.). A duet of short extent and concise form.

DUGAZON, Mme. Rosalie, daughter of an obscure actor named Lefèvre, born at Berlin 1755, died in Paris Sept. 22, 1821. She and her sister began their career as ballet-dancers at the Comédie Italienne, and Rosalie made her first appearance as a singer at the same theatre in 1774. She had an agreeable voice, much feeling and finesse, and played to perfection 'soubrettes,' 'paysannes,' and 'coquettes.' Her most remarkable creation was the part of Nina in Dalayrac's opera of that name. After an absence of three years during the Revolution, she reappeared in 1795, and played with unvarying success till 1806, when she retired. To this day the classes of parts in which she excelled are known as 'jeunes Dugazon' and 'meres Dugazon.'—Her son Gustave (Paris 1782–1826), a pianist and pupil of Berton's, obtained the second 'Prix de Rome' at the Conservatoire in 1806. His operas and ballets, with the exception of 'Aline' (1823), did not succeed.

[ G. C. ]

DULCIMER (Fr. Tympanon; Ital. Cembalo, Timpanon, Salterio tedesco; Germ. Hachbrett). The prototype of the pianoforte, as the psaltery was of the harpsichord. These instruments were so nearly alike that one description might serve for both, were it not for the different manner of playing them, the strings of the dulcimer being set in vibration by small hammers held in the hands, while in the psaltery the sounds were produced by plectra of ivory, metal, or quill, or even the fingers of the performer. It is also no less desirable to separate in description instruments so nearly resembling each other, on account of their ultimate development into the harpsichord and pianoforte by the addition of keys. [See Harpsichord, and Pianoforte.]

Dr. Rimbault (Pianoforte, p. 23) derives dulcimer from 'dulce melos.' Perhaps the 'dulce,'—also used in the old English 'dulsate' and 'dulsacordis,' unknown instruments unless dulcimers—arose from the ability the player had to produce sweet sounds with the softer covered ends of the hammers, just as 'piano' in pianoforte suggests a similar attribute. The Italian 'Salterio tedesco' implies a German derivation for this hammer-psaltery. [See also Cembalo.] The roughness of description used by mediæval Italians in naming one form of psaltery 'strumento di porco,' pig's head, was adopted by the Germans in their faithful translation 'Schweinskopf,' and in naming a dulcimer 'Hackbrett'—a butcher's board for chopping sausage-meat.

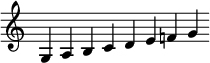

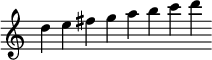

The dulcimer is a trapeze-shaped instrument of not more than three feet in greatest width, composed of a wooden framing enclosing a wrest-plank for the tuning-pins, round which the strings are wound at one end; a soundboard ornamented with two or more sound-holes and carrying two bridges between which are the lengths of wire intended to vibrate; and a hitchpin-block for the attachment of the other ends of the strings. Two, three, four, and sometimes five strings of fine brass or iron wire are grouped for each note. [App. p.619 "English dulcimers have ten long notes of brass wire in unison strings, four or five in number, and ten shorter notes of the same. The first series, struck with hammers to the left of the right-hand bridge, is tuned

the F being natural. The second series, struck to the right of the left-hand bridge, is

the F being again natural. The remainder of the latter series, struck to the left of the left-hand bridge, gives

This tuning has prevailed in other countries and is old. Chromatic tunings are modern and apparently arbitrary."] The dulcimer, laid upon a table or frame is struck with hammers, the heads of which are clothed on either side with hard and soft leather to produce the forte and piano effects. The tone, harsh in the loud playing, is always confused, as there is no damping contrivance to stop the continuance of the sounds when not required. This effect is well imitated in various places in Schubert's 'Divertissement Hongroise.' The compass of two or three octaves, from C or D in the bass clef, has always been diatonic in England, but became chromatic in Germany before the end of the 18th century. As in most mediæval musical instruments ornamentation was freely used on the soundboard, and on the outer case when one existed. The dulcimer and psaltery appear to have come to us from the East, it may be through the Crusades, for the dulcimer has been known for ages in Persia and Arabia, and also in the Caucasus, under the name of 'santir.' Its European use is now limited to the semi-oriental gypsy bands in Hungary and Transylvania. The Magyar name is 'cimbelom.' Mr. Carl Engel ('Descriptive Catalogue,' 1874) points out the remarkable resemblance between an Italian