etc. and this might be treated with its appropriate answer and countersubject, if desired. Some subjects will furnish a stretto in strict canon, and this should be always reserved for the concluding portion of the fugue, by way of climax. If the fugue ends with an episode, such concluding episode is called the Coda (or tail-piece). It is also customary, in fugues of more than two parts, to introduce a Pedal, or point d'orgue, towards the end, which is a long note held out, almost always in the bass part, on which many imitations and strettos can be built which would often be otherwise impracticable. The only notes which can be thus held out as pedals are the dominant and the tonic. The tonic pedal can only be used as a close to the whole piece. The dominant pedal should occur just before the close. It is not necessary to use a tonic pedal in every fugue, but a dominant pedal is almost indispensable.

Fugues for instruments may be written with more freedom than those for voices, but in all kinds the above rules and principles should be maintained. The fugue-form is one of the most important of all musical forms, and all the great classical composers have left us samples of their skill in this department of the art of music. At the same time it must be observed that in the early days of contrapuntal writing the idea of a fugue was very different from that which we now understand by that term. In Morley's 'Plaine and easie Introduction to practicall Musicke,' published in 1597, at p. 76, we find the following definition:—'We call that a fugue, when one part beginneth, and the other singeth the same, for some number of notes (which the first did sing), as thus for example:

This we should now-a-days call a specimen of simple imitation at the octave, in two parts; yet it is from such a small germ as this that the sublime structure of a modern fugue has been gradually developed. Orazio Benevoli (d. 1672) was probably the first of the Italian composers who wrote fugues containing anything like formal development. Later, in the 17th century, however, every Italian composer of church music produced more or less elaborated fugues, those of Leo, Clari, Alessandro Scarlatti, Colonna, Durante, and Pergolesi being among the best.

But it was in Germany that fugue-writing, both vocal and instrumental, reached the highest development and attained the greatest perfection. It would fill a volume to enumerate all the great fuguists of that wonderfully musical nation during the 17th and 18th centuries. Two or three names, however, stand out in bright relief, and cannot be passed over. Sebastian Bach occupies the very pinnacle among fugue-composers, and Handel should be ranked next him. The student should diligently study the fugal works of these great masters, and make them his model. Bach has even devoted a special work to the subject, which is indispensable to the student. [See Art of Fugue.] The treatises of Mattheson, Marpurg, Fux, Albrechtsberger, and André, are also valuable. Among more modern writers may be mentioned Cherubini, Fétis, and Reicha. We abstain from mentioning the works of living authors who have contributed much valuable matter to the literature of this subject. Mozart should be quoted as the first who combined the forms of the sonata and the fugue, as in the overture to 'Die Zauberflöte,' and in the last movement of his 'Jupiter Symphony.'

It is perhaps difficult for a composer at the present day to find a great variety of original fugue-subjects. But the possible ways of treating them are so inexhaustible that a fugue can always be made to appear quite new even though the theme on which it is based be trite and hackneyed. And here we have one of the great advantages of this form of composition—namely, that it does not so absolutely require the origination of really new melodies as every other form necessarily does. But, on the other hand, it does require a command of all the resources of harmony and counterpoint to produce fugues which shall not be mere imitations of what has been done by previous composers; and it also needs genius of a high order to apply those resources so as to avoid the reproach of dryness and lack of interest so often cast upon the fugal style of composition.

[ F. A. G. O. ]

FULL ORGAN. This term, when standing alone, generally signifies that the chief manual, or Great Organ, is to be used, with all its stops brought into requisition. Sometimes the term is employed in an abbreviated form, and with an affix indicating that a portion only of the stops is to be played upon—as 'Full to Fifteenth.' In the last century the expressions 'Full Organ,' 'Great Organ,' and 'Loud Organ,' were severally used to indicate the chief manual organ.

[ E. J. H. ]

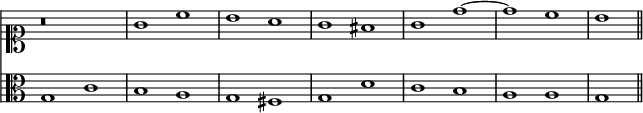

FUNDAMENTAL BASS is the root note of a chord, or the root notes of a succession of chords, which might happen to be the actual bass of a short succession of chords all in their first positions, but is more likely to be partly imaginary, as in the following short succession of complete chords, which has its fundamental bass below on a separate stave:—

Rameau was the first to develop the theory of a fundamental bass, and held that it might 'as