this is by no means an infallible guide, as the same movement if played in a large hall and with a great number of performers would require to be taken somewhat slower than in a smaller room or with a smaller band. In this, as with all other time indications, much must be left to the discretion of the performer or conductor. If he have true musical feeling he cannot go far wrong; if he have not, the most minute directions will hardly keep him right. The word 'allegro' is also used as the name of a piece of music, either a separate piece (e.g. Chopin's 'Allegro de Concert,' op. 46), or as the first movement of a large instrumental composition. In these cases it is generally constructed in certain definite forms, for which see Symphony and Sonata. Beethoven also exceptionally uses the word 'allegro' instead of 'scherzo.' Four instances of this are to be found in his works, viz. in the symphony in C minor, the quartetts in E minor, op. 59, No. 2, and F minor, op. 95, and the Sonata quasi Fantasia, op. 27, No. 1.

[ E. P. ]

ALLEGRETTO (Ital.). A diminutive of 'allegro,' and as a time-indication somewhat slower than the latter, and also faster than 'andante.' Like 'allegro' it is frequently combined with other words, e. g. 'allegretto moderato,' 'allegretto vivace,' 'allegretto ma non troppo,' 'allegretto scherzando,' etc., either modifying the pace or describing the character of the music. The word is also used as the name of a movement, and in this sense is especially to be often found in the works of Beethoven, some of whose allegrettos are among his most remarkable compositions. It may be laid down as a rule with regard to Beethoven, that in all cases where the word 'allegretto' stands alone at the head of the second or third movement of a work it indicates the character of the music and not merely its pace. A genuine Beethoven allegretto always takes the place either of the andante or scherzo of the work to which it belongs. In the seventh and eighth symphonies, in the quartett in F minor, op. 95, and the piano trio in E flat, op. 70, No. 2, an allegretto is to be found instead of the slow movement; and in the sonatas in F, op. 10, No. 2, and in E, op. 14, No. 1, in the great quartett in F, op. 59, No. 1, and the trio in E flat, op. 70, No. 2, the allegretto takes the place of the scherzo. This use of the word alone as the designation of a particular kind of movement is peculiar to Beethoven. It is worth mentioning that in the case of the allegretto of the seventh symphony, Beethoven, in order that it should not be played too fast, wished it to be marked 'Andante quasi allegretto.' This indication however does not appear in any of the printed scores. In the slow movement of the Pastoral Symphony, Beethoven also at first indicated the time as 'Andante molto moto, quasi allegretto,' but subsequently struck out the last two words.

[ E. P. ]

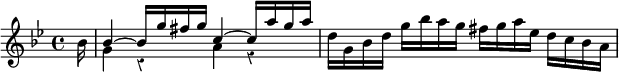

ALLEMANDE. 1. One of the movements of the Suite, and, as its name implies, of German origin. It is, with the exception of the Prelude and the Air, the only movement of the Suite which has not originated in a dance-form. The allemande is a piece of moderate rapidity—about an allegretto—in common time, and commencing usually with one short note, generally a quaver or semiquaver, at the end of the bar.

etc. J. S. Bach. Suites Anglaises, No. 3.

Sometimes instead of one there are three short notes at the beginning: as in Handel's Suites, Book i, No. 5.

etc.

The homophonic rather than the polyphonic style predominates in the music, which frequently consists of a highly figurate melody, with a comparatively simple accompaniment. Suites are occasionally met with which have no allemande (e. g. Bach's Partita in B minor), but where it is introduced it is always, unless preceded by a prelude, the first movement of a suite; and its chief characteristics are the uniform and regular motion of the upper part; the avoidance of strongly marked rhythms or rhythmical figures, such us we meet with in the Courante; the absence of all accents on the weak parts of the bar, such as are to be found in the Sarabande; the general prevalence of homophony, already referred to; and the simple and measured time of the music. The allemande always consists of two parts each of which is repeated. These two parts are usually of the length of 8, 12, or 16 bars; sometimes, though less frequently, of 10. In the earlier allemandes, such as those of Couperin, the second is frequently longer than the first: Bach, however, mostly makes them of the same length.

2. The word is also used as equivalent to the Deutscher Tanz—a dance in triple time, closely resembling the waltz. Specimens of this species of allemande are to be seen in Beethoven's '12 Deutsche Tanze, für Orchester,' the first of which begins thus:—

It has no relation whatever to the allemande spoken of above, being of Swabian origin.

3. The name is also applied to a German national dance of a lively character in 2-4 time, similar to the Contredanse.

[ E. P. ]

ALLGEMEINE MUSIKALISCHE ZEITUNG. see Musikalische Zeitung. [App. p.521 "vol. ii. 115a, 429b, and 430a."]