Their employment obviously presupposes unity and continuity in the works in which they occur. For as long as it is necessary to condescend to the indolence or low standard of artistic perception of audiences by cutting up large musical works into short incongruous sections of tunes, songs, rondos, and so forth, figures illustrating inherent peculiarities of situation and character which play a part throughout the continuous action of the piece are hardly available. Musical dramatic works of the old order are indeed for the most part of the nature of an 'entertainment,' and do not admit of analysis as complete and logical works of art in which music and action are co-ordinate. But when it becomes apparent that music can express most perfectly the emotional condition resulting from the action of impressive outward circumstances on the mind, the true basis of dramatic music is reached; and by restricting it purely to the representation of that inward sense which belongs to the highest realisation of the dramatic situations, the principle of continuity becomes as inevitable in the music as in the action itself, and by the very same law of artistic congruity the 'leit-motive' spring into prominence. For it stands to reason that where the music really expresses and illustrates the action as it progresses, the salient features of the story must have salient points of music, more marked in melody and rhythm than those portions which accompany subordinate passages in the play; and moreover when these salient points are connected with ideas which have a common origin, as in the same personage or the same situation or idea, these salient points of music will probably acquire a recognisable similarity of melody and rhythm, and thus become 'leit-motive.'

Thus, judging from a purely theoretical point of view, they seem to be inevitable wherever there is perfect adaptation of music to dramatic action. But there is another important consideration on the practical side, which is the powerful assistance which they give to the attention of the audience, by drawing them on from point to point where they might otherwise lose their way. Moreover they act in some ways as a musical commentary and index to situations in the story, and sometimes enable a far greater depth of pregnant meaning to be conveyed, by suggesting associations with other points of the story which might otherwise slip the notice of the audience. And lastly, judged from the purely musical point of view, they occupy the position in the dramatic forms of music which 'subjects' do in pure instrumental forms of composition, and their recurrence helps greatly towards that unity of impression which it is most necessary to attain in works of high art.

As a matter of fact 'leit-motive' are not always identical in statement and restatement; but as the characters and situations to which they are appropriate vary in their surrounding circumstances in the progress of the action, so will the 'leit-motive' themselves be analogously modified. From this springs the application of variation and 'transformation of themes' to dramatic music; but it is necessary that the treatment of the figures and melodies should be generally more easily recognisable than they need to be in abstract instrumental music.

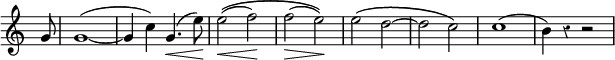

Leit-motive are perfectly adapted to instrumental music in the form known as 'programme music,' which implies a story, or some definite series of ideas; and it is probable that the earliest distinct recognition of the principle in question is in the Symphonie Fantastique of Berlioz (written before 1830), where what he calls an 'idée fixe' is used in the manner of a leit-motif. The 'idée fixe' itself is as follows:—

It seems hardly necessary to point to Wagner's works as containing the most remarkable examples of 'leit-motive,' as it is with his name that they are chiefly associated. In his earlier works there are but suggestions of the principle, but in the later works, as in Tristan and the Niblung series, they are worked up into a most elaborate and consistent system. The following examples will serve to illustrate some of the most characteristic of his 'leit-motive' and his use of them.

The curse which is attached to the Rheingold ring is a very important feature in the development of the story of the Trilogy, and its 'leitmotif,' which consequently is of frequent occurrence, is terribly gloomy and impressive. Its first appearance is singularly apt, as it is the form in which Alberich the Niblung first declaims the curse when the ring is reft from him by Wotan, as follows:—

etc.

Among the frequent reappearances of this motif, two may be taken as highly characteristic. One is towards the end of the Rheingold. where Fafner kills his brother giant Fasolt for the possession of the ring, and the leit-motif