became a party tune in Ireland, especially after 'Dublin's Deliverance; or the Surrender of Drogheda,' beginning

Protestant boys, good tidings I bring,

and 'Undaunted Londonderry,' commencing

Protestant boys, both valiant and stout,

had been written to it.

It has long ago lost any party signification in England, but it was discontinued as a march in the second half of the last century, in order to avoid offence to our Irish soldiers of the Roman Catholic faith.

The tune has been often referred to by dramatists and by other writers, as by Shadwell and Vanbrugh in plays, and by Sterne in Tristram Shandy. Purcell claims it as 'A new Irish tune' by 'Mr. Purcell' in the second part of Music's Handmaid, 1689, and in 1691 he used it as a ground-bass to the fifth piece in The Gordian Knot unty'd. The first strain has been commonly sung as a chorus in convivial parties:

A very good song, and very well sung,

Jolly companions every one.

And it is the tune to the nursery rhyme:

There was an old woman toss'd up on a blanket

Ninety-nine times as high as the moon.

A large number of other songs have been written to the air at various times.

[ W. C. ]

LILT (Verb and Noun), to sing, pipe, or play cheerfully, or, according to one authority, even sadly; also, a gay tune. The term, which is of Scottish origin, but is used in Ireland, would seem to be derived from the bagpipe, one variety of which is described in the 'Houlate' (an ancient allegorical Scottish poem dating 1450), as the 'Liltpype.' Whenever, in the absence of a musical instrument to play for dancing, the Irish peasant girls sing lively airs to the customary syllables la-la-la, it is called 'lilting.' The classical occurrence of the word is in the Scottish song, 'The Flowers of the Forest,' a lament for the disastrous field of Flodden, where it is contrasted with a mournful tone:—

I've heard them liltin' at the ewe milkin',

Lasses a liltin' before dawn of day;

Now there's a moanin' on ilka green loanin',

The Flowers of the Forest are a' wede away.

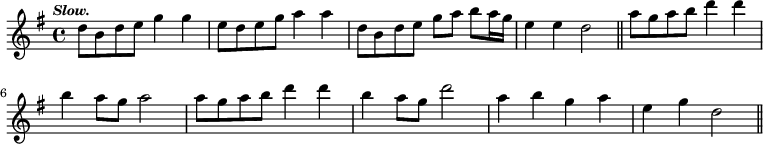

The Skene MS., ascribed (though not [1]conclusively) to the reign of James VI. of Scotland, contains six Lilts: 'Ladie Rothemayeis' (the air to the ballad of the Burning of Castle Frindraught), 'Lady Laudians' (Lothian's), 'Ladie Cassilles' (the air of the ballad of Johnny Faa), Lesleis, Aderneis, and Gilcreich's Lilts. We quote 'Ladie Cassilles':—

Mr. Dauney, editor of the Skene MS., supposes the Liltpipe to have been a shepherd's pipe, not a bagpipe, and the Lilts to have sprung from the pastoral districts of the Lowlands.

[ R. P. S. ]

LILY OF KILLARNEY. A grand opera ia 3 acts, founded on Boucicault's 'Colleen Bawn'; the words by John Oxenford, the music by Jules Benedict. Produced at the Royal English Opera, Covent Garden, Feb. 8, 1862.

[ G. ]

LIMPUS, Richard, organist, born Sept. 10, 1824, was a pupil of the Royal Academy of Music, and organist successively of Brentford; of St. Andrew's, Undershaft; and St. Michael's, Cornhill. He composed a good deal of minor music, but his claim to remembrance is as founder of the College of Organists, which owing to his zeal and devotion was established in 1864. He was secretary to the College till his death, March 15, 1875. [See Organists, College of.]

[ G. ]

LINCKE,[2] Joseph, eminent cellist and composer, born June 8, 1783, at Trachenberg in Prussian Silesia; learnt the violin from his father, a violinist in the chapel of Prince Hatzfeld, and the cello from Oswald. A mismanaged sprain of the right ancle left him lame for life.[3] At 10 he lost his parents, and was obliged to support himself by copying music, until in 1800 he procured a place as violinist in the Dominican convent at Breslau. There he studied the organ and harmony under Hanisch, and also pursued the cello under Lose, after whose departure he became first cellist at the theatre, of which C. M. von Weber was then Capellmeister. In 1808 he went to Vienna, and was engaged by Prince Rasoumowsky[4] for his private quartet-party, at the suggestion of Schuppanzigh. In that house, where Beethoven was supreme, he had the opportunity of playing the great composer's works under his own supervision.[5] Beethoven was much attached to Lincke, and continually calls him 'Zunftmeister violoncello,' or some other droll name, in his letters. The Imperial library at Berlin[6] contains a comic canon in Beethoven's writing on the names Brauchle and Lincke.

[App. p.701 "In the musical example, the sign ![]() should be over the third bar of the canon."]

should be over the third bar of the canon."]

The two Sonatas for P.F. and Cello (op. 102) were composed by Beethoven while he and Lincke were together at the Erdödys in 1815.[7]

Lincke played in Schuppanzigh's public quartets, and Schuppanzigh in turn assisted Lincke at his farewell concert, when the programme consisted entirely of Beethoven's music, and the

- ↑ See Mr. Chappell's criticisms, 'Popular Music,' p. 614.

- ↑ He always wrote his name thus, though it is usually spelled Linke.

- ↑ It is perhaps in allusion to this that Bernard writes. 'Lincke has only one fault—that he is crooked' (Krumm).

- ↑ Weiss played the viola, and the Prince the second violin.

- ↑ Compare Thayer's Beethoven, iii. 49.

- ↑ See Nohl's Beethoven's Briefe, 1867, p. 92. note.

- ↑ See Thayer, iii. 343.