instead of being, as afterwards, subsidiary in a musical sense. The impressive effect attained by Handel—by simple means—in the piece just referred to, has been paralleled in more recent tunes by Beethoven's employment of larger orchestral resources, in the sublime 'Marcia Funebre' in his 'Sinfonia Eroica.'

The March usually begins with a crotchet before the commencing phrase, as in Handel's Marches in 'Rinaldo' (1711), in 'Scipio,' the Occasional Overture, etc. There are however numerous instances to the contrary, as in Gluck's March in 'Alceste,' that in Mozart's 'Die Zauberflöte,' and Mendelssohn's Wedding March, which latter presents the unusual example of beginning on a chord remote from the key of the piece. A March of almost equal beauty is that in Spohr's Symphony 'Die Weihe der Töne,' and here (as also in the March just referred to) we have an example of a feature found in some of the older Marches—the preliminary flourish of trumpets, or Fanfare [see vol. i. p. 502b].

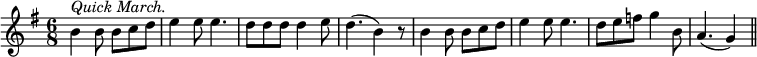

There is also, as already said, a description of march in half time—2-4 (two crotchets in a bar), called with us the Quick March—Pas redoublé, Geschwind Harsch. Good specimens of this rhythm are the two Marches (Pianoforte duets) by Schubert, No. 3, op. 40, and No. 1, op. 51, in the latter of which we have also the preliminary fanfare. The march form in pianoforte music has indeed been used by several modern composers: by Beethoven in his three Marches for two performers (op. 45); and the Funeral March in his Sonata, op. 26; and, to a much greater extent, by Franz Schubert in his many exquisite pieces of the kind for four hands, among them being two (op. 121) in a tempo (6-8), sometimes, but not, often, employed in the march style: another such specimen being the 'Rogues' March,' associated for more than a century (probably much longer) with army desertion. This is also in the style of the Quick March, the tune being identical with that of a song once popular, entitled 'The tight little Island'—it having, indeed, been similarly employed in other instances. The following is the first part of this March, whose name is better known than its melody:—

Besides the March forms already referred to, there is the Torch-dance [see Fackeltanz, vol. i. p. 501a], which, however, is only associated with pageants and festivities. These and military marches being intended for use in the open air, are of course written entirely for wind instruments, and those of percussion; and in the performance of these pieces many regimental bands, British and foreign, have arrived at a high degree of excellence.

[ H. J. L. ]

MARCHAND, Louis, a personage whose chief claim to our notice is his encounter with Bach, and, as might be imagined, his signal defeat. He was born at Lyons Feb. 2, 1669.[1] He went to Paris at an early age, became renowned there for his organ-playing, and ultimately became court organist at Versailles. By his recklessness and dissipated habits he got into trouble, and was exiled in 1717. The story goes, that the king, taking pity on Marchand's unfortunate wife, caused half his salary to be withheld from him, and devoted to her sustenance. Soon after this arrangement, Marchand coolly got up and went away in the middle of a mass which he was playing, and when remonstrated with by the king, replied, 'Sire, if my wife gets half my salary, she may play half the service.' On account of this he was exiled, on which he went to Dresden, and there managed to get again into royal favour. The King of Poland offered him the place of court organist, and thereby enraged Volumier, his Kapellmeister, who was also at Dresden, and who, in order to crush his rival, secretly invited Bach to come over from Weimar. At a royal concert, Bach being incognito among the audience, Marchand played a French air with brilliant variations of his own, and with much applause, after which Volumier invited Bach to take his seat at the clavecin. Bach repeated all Marchand's showy variations, and improvised twelve new ones of great beauty and difficulty. He then, having written a theme in pencil, handed it to Marchand, challenging him to an organ competition on the given subject. Marchand accepted the challenge, but when the day came it was found that he had precipitately fled from Dresden, and, the order of his banishment having been withdrawn, had returned to Paris, where his talents met with more appreciation. He now set up as a teacher of music, and soon became the fashion, charging the then unheard-of sum of a louis d'or a lesson. In spite of this, however, his expensive habits brought him at last to extreme poverty, and he died in great misery, Feb. 17, 1732. His works comprise 2 vols. of pieces for the clavecin, and one for the organ, and an opera, 'Pyramus et Thisbe,' which was never performed.

His ideas, says Fétis, are trivial, and his harmonies poor and incorrect. There is a curious criticism of him by Rameau, quoted in La Borde, 'Essai sur la musique' (vol. iii.), in which he says that 'no one could compare to Marchand in his manner of handling a fugue'; but, as Fétis shows, this may be explained by the fact that Rameau had never heard any great German or Italian organist.

[ J. A. F. M. ]

MARCHESI, Luigi, sometimes called Marchesini, was born at Milan, 1755. His father, who played the horn in the orchestra at Modena, was his first teacher; but his wonderful aptitude for music and his beautiful voice soon attracted

- ↑ Spitta, whose accuracy and judgment are unimpeachable, in his Life of Bach gives the date 1671, as an inference from an old engraving. But see Fétis (s.v.), who quotes an article In the Magazln Encyclopédique, 1812, tom. iv. p. 341. where this point is thoroughly investigated, and a register of Marchand's birth given.