(as it must be), other classes cannot safely be classed as Diatonic and Chromatic in relation to ends, without liability to confusion. And lastly, the term Modulation itself clearly implies the process and not the result. Therefore in this place the classification will be taken to apply to the means and not to the end, to the process by which the modulation is accomplished and not the keys which are thereby arrived at.

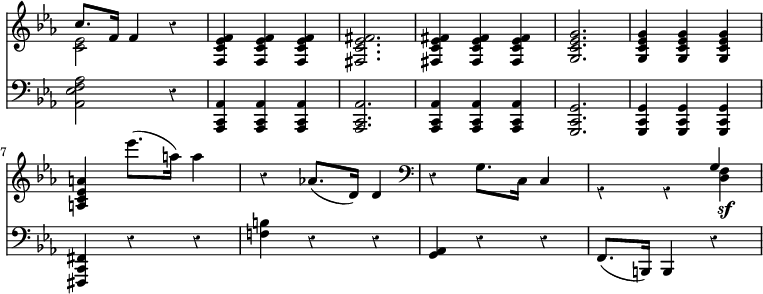

The Diatonic forms, then, are such as are effected by means of notes or chords which are exclusively diatonic in the keys concerned. Thus in the following example (Bach, Well-tempered Clavier, Bk. 2, no. 12):—

etc.

the chord at * indicates that F has ceased to be the tonic, as it is not referable to the group of harmonies characteristic of that key. However, it is not possible to tell from that chord alone to what key it is to be referred, as it is equally a diatonic harmony in either B♭, E♭, or A♭; but as the chords which follow all belong consistently to A♭, that note is obviously the tonic of the new key, and as the series is Diatonic throughout it belongs to the Diatonic class of modulations.

The Chromatic is a most ill-defined class of modulations; and it is hardly to be hoped that people will ever be sufficiently careful in small matters to use the term with anything approaching to clear and strict uniformity of meaning. Some use it to denote any modulation in the course of which there appear to be a number of accidentals—which is perhaps natural but obviously superficial. Others again apply the term to modulations from one main point to another through several subordinate transitions which touch remote keys. The objection to this definition is that each step in the subordinate transitions is a modulation in itself, and as the classification is to refer to the means, it is not consistent to apply the term to the end in this case, even though subordinate. There are further objections based upon the strict meaning of the word Chromatic itself, which must be omitted for lack of space. This reduces the limits of chromatic modulation to such as is effected through notes or chords which are chromatic in relation to the keys in question. Genuine examples of this kind are not so common as might be supposed; the following example (Beethoven, op. 31, no. 3), where passage is made from E♭ to C is consistent enough for illustration:—

The third class, called Enharmonic, which tenda to be more and more conspicuous in modern music, is such as turns mainly upon the translation of intervals which, according to the fixed distribution of notes in the modern system, are identical, into terms which represent different harmonic relations. Thus the minor seventh, G-F, appears to be the same interval as the augmented sixth G-E♯; but the former belongs to the key of C, and the latter either to B or F♯, according to the context. Again, the chord which is known as the diminished seventh is frequently quoted as affording such great opportunities for modulation, and this it does chiefly enharmonically; for the notes of which it is composed being at equal distances from each other can severally be taken as third, fifth, seventh or ninth of the root of the chord, and the chord can be approached as if belonging to any one of these roots, and quitted as if derived from any other. The passage quoted from the Leonore Overture in the article Change (vol. i. p. 333a) may be taken as an example of an enharmonic modulation which turns on this particular chord.

Enharmonic treatment really implies a difference between the intervals represented, and this is actually perceived by the mind in many cases. In some especially marked instances it is probable that most people with a tolerable musical gift will feel the difference with no more help than a mere indication of the relations of the intervals. Thus in the succeeding example the true major sixth represented by the A♭-F in (a) would have the ratio 5:3 ( = 125:75), whereas the diminished seventh represented by G♯-F♮ in (b) would have the ratio 128:75; the former is a consonance and the latter, theoretically, a rough dissonance, and though they are both represented by the same notes in our system, the impression produced by them is to a certain extent proportionate to their theoretical rather than to their actual constitution.