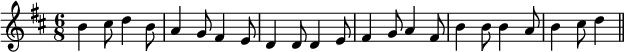

and a lesson of Nicolai's performed on the harpsichord by the sisters of his friend. Among his musical acquaintances were one Wesley Doyle, a musician's son, who published some songs at Chappell's in 1822, and Joe, the brother of Michael Kelly, the author of the 'Reminiscences.' Moore sang effectively upon these occasions some of the songs of Dibdin, then immensely popular. He now received lessons from Warren, subsesequently organist of the Dublin cathedrals, and a pupil of Dr. Philip Cogan, a noted extemporiser upon Irish melodies: but neither Doyle nor Warren's example or precept produced any effect until the future bard began to feel personal interest in music. Subsequently he says, 'Billy Warren soon became an inmate of the family: I never received from him any regular lessons; yet by standing often to listen while he was instructing my sister, and endeavouring constantly to pick out tunes, or make them when I was alone, I became a pianoforte player (at least sufficiently so to accompany my own singing) before almost any one was aware of it.' He produced a sort of masque at this time, and sang in it an adaptation of Haydn's 'Spirit-song,' to some lines of his own. On occasion of some mock coronation held at the rocky islet of Dalkey, near Dublin, Moore met Incledon, who was then and there knighted as Sir Charles Melody, the poet contributing an ode for the sportive occasion. It was the metrical translation or paraphrase of Anacreon, subsequently dedicated to the Prince Regent, that first brought Moore into public notice; about this time he alludes to the 'bursting out of his latent talent for music': further quickened by the publication of Bunting's first collection of Irish melodies in the year 1796. From this collection Moore (greatly to Bunting's chagrin) selected eleven of the sixteen airs in the first number of his Irish melodies; Bunting averred that not only was this done without acknowledgement, but that Moore and his coadjutor Stevenson had mutilated the airs. That Bunting's censures were not without foundation will appear from Carolan's air 'Planxty Kelly,' one strain of which—

was altered by Moore to the following:—

Even this ending (on a minim) is incorrect, the portion of the original air here used being

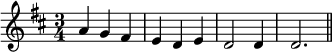

In 'Go where glory waits thee,' the ending as given by Moore destroys what in the article Irish Music we have called the narrative form; it should end as follows:—

The air was however altered thus to suit Moore's lines:—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 \key f \major \relative f' { \autoBeamOff f4 g8 a16[ bes] a8 g | f2. \bar "||" }

\addlyrics { O still re -- mem -- ber me. } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/p/np5j9qabbwajfluh5l4wh2m2pu97kmv/np5j9qab.png)

The song 'Rich and rare' ends thus in the original:—

The version of Moore is perhaps an improvement, but it is an alteration:—

Moore took to himself whatever blame these changes involved, and even defended the often rambling and inappropriate preludes of Stevenson, which he fancifully compared to the elaborate initial letters of mediaeval MSS. Moore wrote 125 of these beautiful and now famous poems. His singing of them to his own accompaniment has been frequently described as indeed deficient in physical power, but incomparable as musical recitation: not unfrequently were the hearers moved to tears, which the bard himself could with difficulty restrain; indeed it is on record that one of his lady listeners was known to faint away with emotion. Mr. N. P. Willis says, 'I have no time to describe his (Moore's) singing; its effect is only equalled by his own words. I for one could have taken him to my heart with delight!' Leigh Hunt describes him as playing with great taste on the piano, and compares his voice as he sang, to a flute softened down to mere breathing. Jeffrey, Sydney Smith, and Christopher North are equally eloquent; nay, even the utterly unmusical Sir W. Scott calls him the 'prettiest warbler he had ever known'; while Byron, almost equally deficient in musical appreciation, was moved to tears by his singing. Moore felt what he expressed, for as an illustration of the saying, 'Si vis me flere, dolendum est primum ipsi tibi,' it is recorded that on attempting 'There's a song of the olden time,' a favourite ditty of his father, for the first time after the old man's death, he broke down, and had to quit the room, sobbing convulsively.

Although as an educated musician Moore had no repute, yet, like Goldsmith, he now and then undertook to discuss such topics as harmony and counterpoint, of which he knew little or nothing. Thus we find him gravely defending consecutive fifths, and asking naïvely whether there might not be some pedantry in adhering to the rule which forbids them? That he was largely gifted with the power of creating melody, is apparent from his airs to various lines of his own; amongst them 'Love thee, dearest,' 'When midst the gay,' 'One dear smile'; and 'The Canadian boatsong,' long deemed a native air, but latterly claimed by Moore. Many of his little concerted pieces attained great popularity. The terzetto 'O, lady fair' was at one time sung everywhere; a little three-part glee, 'The Watchman'—describing two lovers, unwilling to part, yet constantly