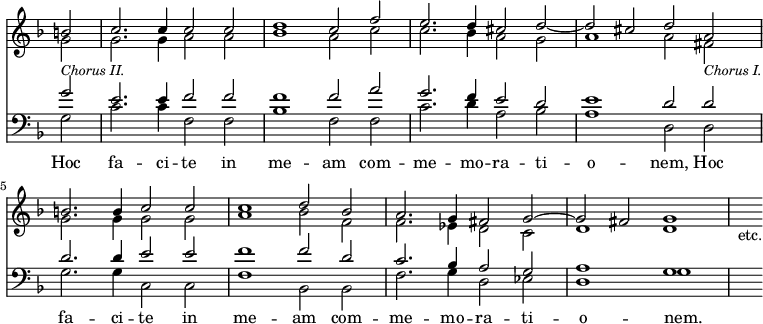

many were lost through the carelessness of the Maestro's son, Igino. The entire contents of the seven printed volumes, together with seventy-two of the Motets hitherto existing only in MS., have already been issued as a first instalment of the complete edition of Palestrina's works now in course of publication by Messrs. Breitkopf & Härtel of Leipzig; and this, probably, is as many as we can now hope for, as it is well known that some of the MS. copies we have mentioned are incomplete. Among so many gems, it is difficult to select any number for special notice. Perhaps the finest of all are those printed in the Fourth Book of Motets for five Voices, the words of which are taken from the Book of Canticles: but, the two Books of simpler compositions for four Voices are full of treasures. Some are marvels of contrapuntal cleverness; others—where the character of the words is more than usually solemn—as unpretending as the plainest Faux bourdon. As an example of the more elaborate style, we transcribe a few bars of 'Sicut cervus desiderat,' contrasting them with a lovely passage from 'Fratres ego enim accepi,' a Motet for eight Voices, in which the Institution of the Last Supper is illustrated by simple harmonies of indescribable beauty.

Sicut cervus.

Fratres ego.

Palestrina's greatest contemporaries, in the Roman School, were, Vittoria, whose Motets are second only in importance to his own, Morales, Felice and Francesco Anerio, Bernadino and Giovanni Maria Nanini, Luca Marenzio, and Francesco Suriano. The honour of the Flemish School was supported, to the last, by Orlando di Lasso, a host in himself. The Venetian School boasted, after Willaert, Cipriano di Rore, Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, and, especially, Giovanni Croce, the originality of whose style was only exceeded by its wonderful delicacy and sweetness, which are well shewn in the following example.

In England, the Motet was cultivated, with great success, by some of the best Composers of the best period. The 'Cantiones sacræ' of Tallis and Byrd, will bear comparison with the finest productions of the Roman or any other School, those of Palestrina alone excepted. And, besides these, we possess a number of beautiful Motets by Dr. Tye, John Taverner, John Shepherd, Dr. Fayrfax, Robert Johnson, John Digon, John Thorne, and several other writers not unknown to fame. Though the Latin Motet was, as a matter of course, banished from the Services of the Church after the change of Religion, its style still lived on, in the Full Anthem, of which so many glorious examples have been handed down to us, in our Cathedral Choir-books; for, the Full Anthem is a true Motet, notwithstanding the language in which it is sung; and it is certain that some of the purest specimens of the style were originally written in Latin, and adapted to English words, afterwards—as in the case of Byrd's 'Civitas sancti tui,' now always sung as 'Bow thine ear, Lord.' Orlando Gibbons's First (and only) Set of 'Madrigals and Mottets,' printed in 1612, furnishes a singular return to the old use of the word. They are all Sæcular Songs; as are, also, Martin Pierson's 'Mottects,' published eighteen years later.

The Sixth Epoch, beginning with the early years of the 17th Century, was one of sad deca-