which is played at the beginning. [Appoggiatura.]

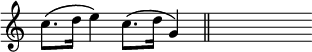

Like all graces, the Nachschlag forms part of the value of its principal note, which is accordingly curtailed to make room for it, just as in the Vorschlag the principal note loses a portion of its value at the beginning. Emanuel Bach, who is the chief authority on the subject of grace-notes, does not approve of this curtailment. He says 'All graces written in small notes belong to the next following large note, and the value of the preceding large note must therefore never be lessened.' And again 'The ugly Nachschlag has arisen from the error of separating the Vorschlag from its principal note, and playing it within the value of the foregoing note,' and he gives the following passage as an instance, which he considers would be far better rendered as in Ex. 4 than as in Ex. 3.

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 2/4 \relative c'' { c8_[^"2." \grace d b \grace c a \grace b g] \bar "||" c16.[^"3." d32 b16. c32 a16. b32 g8] \bar "||" c8[^"4." d32 b16. c32 a16. b32 g16.] \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/7/1/718632kqc27gm8ajtkw9bydb7on2oho/718632kq.png)

Nevertheless, Emanuel Bach's successors, Marpurg, Türk, Leopold Mozart, etc., have all recognised the Nachschlag as a legitimate grace, though they all protest against its being written as a small note, on account of its liability to be confounded with the Vorschlag. Marpurg refers to an early method of indicating it by means of a bent line (![]() Music characters), the angle being directed upwards or downwards according as the Nachschlag was above or below the principal note (Ex. 5), while for a springing Nachschlag, the leap of which was always into the next following principal note, an oblique line was used (Ex. 6). 'But at the present day (1755),' he goes on to say, 'the Nachschlag is always written as a small note, with the hook turned towards its own principal note' (Ex. 7).

Music characters), the angle being directed upwards or downwards according as the Nachschlag was above or below the principal note (Ex. 5), while for a springing Nachschlag, the leap of which was always into the next following principal note, an oblique line was used (Ex. 6). 'But at the present day (1755),' he goes on to say, 'the Nachschlag is always written as a small note, with the hook turned towards its own principal note' (Ex. 7).

The Nachschlag was not limited to a single note, groups of two notes (called by Türk the double Nachschlag) forming a diatonic progression, and played at the end of their principal note, being frequently met with, and groups of even more notes occasionally.

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 2/4 \mark \markup { \smaller "8." } \relative c'' { \afterGrace c4\( { b16[ c] } d8\) r | \afterGrace c4\( { d8[ c b] } a\) r \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/6/u/6ut5qip2pcfonsz382g3ze62ga972ri/6ut5qip2.png)

In the works of the great masters, the Nachschlag, though of very frequent occurrence, is almost invariably written out in notes of ordinary size, as in the following instances, among many others.

Handel, 'Messiah.'

![{ \time 3/4 \key d \major \partial 4 \mark \markup { \smaller 9. } \relative a'' { a4 | e8.[ fis16 e8. fis16 e8. fis16] | g4 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/o/2o1agdy78wol9jppsuu5ef0hhtyidod/2o1agdy7.png)

Beethoven, Symphony No. 7.

Mendelssohn, Cello Sonata, Op. 45.

Bach, Fugue No. 1. (Double Nachschlag.)

Modern composers, on the other hand, have returned to some extent to the older method of writing the Nachschlag as a small note, apparently not taking into account the possibility of its being mistaken for a Vorschlag. It is true that in most cases there is practically little chance of a misapprehension, the general character and rhythm of the phrase sufficiently indicating that the small notes form a Nachschlag. Thus in many instances in Schumann's pianoforte works the small note is placed at the end of a bar, in the position in which as Nachschlag it ought to be played, thus distinguishing it from the Vorschlag, which would be written at the beginning of the bar (Ex. 10). And in the examples quoted below from Liszt and Chopin, although the same precaution has not been taken, yet the effect intended is sufficiently clear the small notes all fall within the time of the preceding notes (Ex. 11).

Schumann, 'Warum,' Op. 12.

Liszt, 'Rhapsodie Hongroise,' No. 2.

![{ \time 2/4 \key e \major \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \mark \markup { \smaller 11. } \relative c' { << { \grace cis8 cis2 | \grace { dis16[ b cis] } \afterGrace b2 ~ { b16[ cis e d cis] } | cis2 \bar "||" } \\ { \afterGrace r4 { <gis eis>8 } q r | \afterGrace r4 { <fis d>8 } q4 } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/a/talk24ffntko7dysmkh1x46z2ixvvan/talk24ff.png)

Chopin, Nocturne, Op. 32, No. 2.

![{ \time 4/4 \key aes \major \relative d'' { des4 \grace c8 \afterGrace c4 { c8[ des c b c b' aes ees c] } a4( bes8) r \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/6/5/65p6jm1sg3a0kj4c1ym2axxkcxdrel6/65p6jm1s.png)