notes, of which the second was the highest. Its figure varied considerably in different MSS.

4. The Clivis, Clinis, or Flexa, indicated a group of two notes, of which the second was the lowest. This, also, varied very much in form.

5. The Scandicus denoted a group of three ascending notes.

6. The Climdeus denoted three notes, descending.

7. The Cephalicus—sometimes identified with the Torculus—represented a group of three notes, of which the second was the highest.

8. The Flexa resupina—described by some writers as the Porrectus—indicated a group of three notes, of which the second was the lowest.

9. The Flexa strophica indicated three notes, of which the second was lower than the first, and the third a reiteration of the second.

10. The Quilisma was originally a kind of shake, or reiterated note; but in later times its meaning became almost identical with that of the Scandicus.

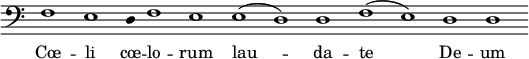

These, and others of less general importance—as the Ancus, Oriscus, Salicus, Pressus, Tramea, etc., etc.—were frequently combined into forms of great complexity, of which a great variety of examples, accurately figured, and minutely described, will be found in the works of Gerbert, P. Martini, Coussemaker, Kiesewetter, P. Lambillotte, Ambros, and the Abbé Raillard. Beyond all doubt, they were, originally, mere Accents, analogous to those of Alexandrian Greek, and intended rather as aids to declamation, than to actual singing: but, a more specific meaning was soon attached to them. They served to point out, not only the number of the notes which were to be sung to each particular syllable of the Poetry, but, in a certain sense, the manner in which they were to be treated. This was a most important step in advance; yet, the new system had also its defects. Less definite, as indications of pitch, than the Letters they displaced, the Neumæ did, indeed, shew at a glance the general conformation of the Melody they were supposed to illustrate, but entirely failed to warn the Singer whether the Interval by which he was expected to ascend, or descend, was a Tone, or a Semitone, or even a Second, Third, Fourth, or Fifth. Hence, their warmest supporters were constrained to admit, that, though invaluable as a species of memoria technica, and well fitted to recal a given Melody to a Singer who had already heard it, they could never—however carefully (curiose) they might be drawn enable him to sing a new or unknown Melody at sight. This will be immediately apparent from the following antient example, quoted by P. Martini in the first volume of his 'Storia di Musica':

Towards the close of the 8th century, we find certain small letters interspersed among the more usual Neumæ. In the celebrated 'Antiphonarium' of S. Gall[1]—an invaluable MS., which has long been received, on very weighty evidence, as a faithful transcript of the Antiphonary of S. Gregory—these small letters form a conspicuous feature in the Notation; and they are, beyond all doubt, the prototypes of our so-called 'Dynamic Signs,' the earliest recorded indications of Tempo and Expression. It is amusing to find our familiar forte foreshadowed by a little f (diminutive of fragor); and tenuto, or ben tenuto, by t, or bt (teneatur, or bene teneatur). A little c stands for celeriter (con moto); and other letters are used, which are interesting as signs of a growing desire for something more than an empty rendering of mechanical sounds. But, about the year 900,[2] a far greater improvement was brought into general use—an invention which contains within itself the germ of all that is most logical, and, practically, most enduring, in our present perfect system. The idea was very simple. A long red line, drawn horizontally across the parchment, formed the only addition to the usual scheme. All Neumæ, placed directly upon this line, were understood to represent the note F. Graver sounds were denoted by characters placed below, and more acute ones by others drawn above it. Thus, while the position of one note was absolutely fixed, that of others was rendered much more definite than heretofore.

The advantage of this new plan was so obvious, that a yellow line, intended to represent C, was soon added, at some little distance above the red cue. This quite decided the position of two notes; and, as it was evident that every note placed between the two lines must necessarily be either G, A, or B, the place of the others was no longer very difficult to determine.

- ↑ Printed, at Brussels, in fac-simile, by P. Lambillotte, in 1861. The first page is also given in the 2nd vol. of Pertz's 'Monumenta Germaniae historica.' All authorities agree in regarding the MS. as one of the most interesting reliques of early Notation we possess; but it is only right to say that its date has been hotly disputed, and that doubt has even been thrown upon the identity of its forms with those used in the older Antiphonarium.

- ↑ It is impossible to give the exact date. The antiquity of MSS. can very rarely be proved beyond the possibility of cavil.