and Oboe, which brings it out in quite a new and unexpected light—

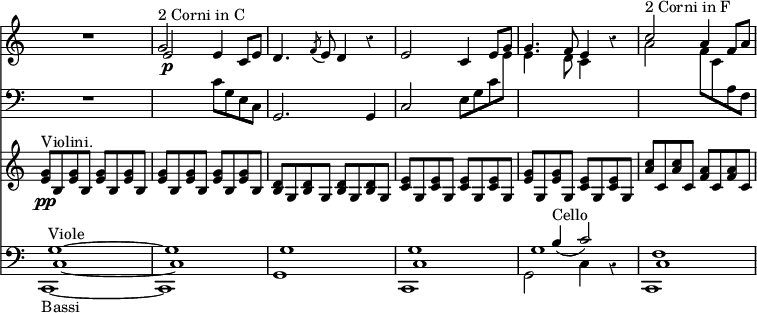

Sometimes we find this order reversed; the subject being given to the Wind, and the accompaniment to the Stringed Instruments; as in the opening movement of Weber's Overture to 'Der Freischütz'—

In either case, the successful effect of the passage depends entirely upon the completeness of the stringed skeleton. A weak point in this—whether the principal subject be assigned to it or not—renders it wholly unfit to support the harmony of the Wind Instruments, and deprives the general structure of that firmness which it is one of the chief objects of the great Master to secure.

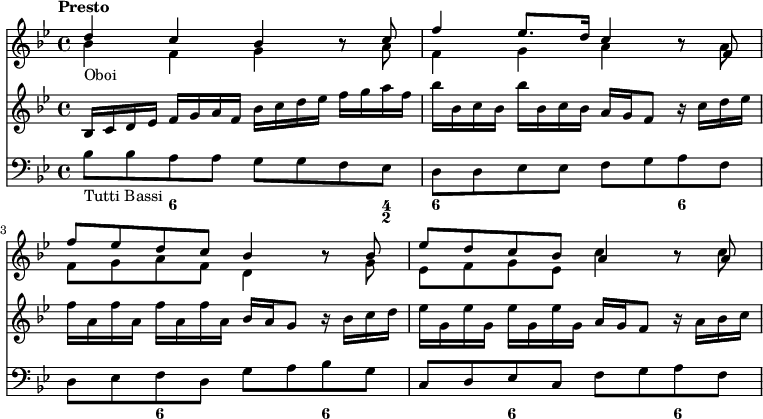

II. Breadth of tone is dependent upon several conditions; not the least important of which is the necessity for writing for every instrument with a due regard to its individual peculiarities. This premised, there is little fear of thinness, when the stringed parts are well arranged, and strengthened, where necessary, by Wind Instruments, which may either be played in unison with them—as in the Overture to 'Jephtha,' where Handel has reinforced the Violins by Oboes, and the Basses by Bassoons—or so disposed as to enrich the harmony in any other way best suited to the style of particular passages—as in that to 'Acis and Galatea,' in which the Oboes are used for filling in the harmonies indicated by the Figured Bass, while a brilliant two-part counterpoint, so perfect in itself that it scarcely seems to need anything to add to its completeness, is played by the Violins and Basses, the latter, as indicated by the expression Tutti Bassi, being strengthened by the Bassoons—

Among more modern writers, Beethoven stands pre-eminent for richness of tone, which he never fails to attain, either by careful distribution of his harmony among the instruments he employs, or in some other way suggested by his ever-ready