and Bassoons in the 'Quoniam tu solus' of his Mass in B minor—

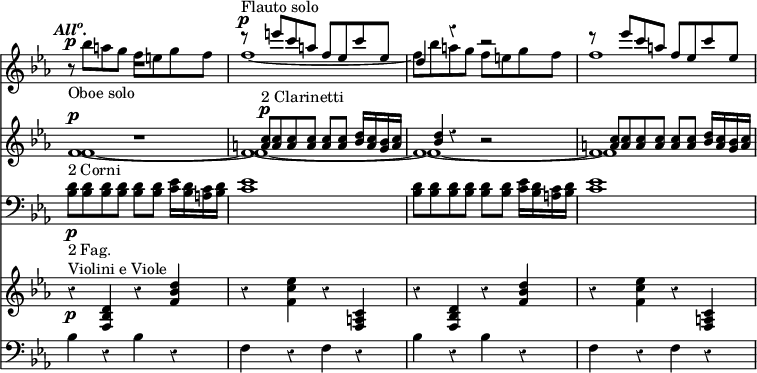

As new Wind Instruments were invented, or old ones improved, the power of producing variety of colouring became, of course, immeasurably increased. Haydn took signal advantage of this circumstance in the 'Creation' and the 'Seasons': but Mozart's delightful system of Instrumentation surpasses, in beauty, that of all his contemporaries. His alternations of light and shade are endless. Every new phrase introduces us to a new effect; and every Instrument in the Orchestra is constantly turned to account, always with due regard to its character and capabilities, and always with a happy result. In the following passage from the Overture to 'Die Zauberflöte,' for instance, the whole strength of the Wood Wind is so employed as to shew off every Instrument at its best, while the stringed accompaniment gives point to the idea, and the sustained notes on the Horns add just support enough to perfect its beauty—

It would be incorrect to say that Beethoven was a greater master of this peculiar phase of Instrumentation than Mozart; though in this, as in everything else, he certainly repeated his own ideas less frequently than any writer that ever lived. The wealth of invention exhibited in the orchestral effects of this Composer—even in those of his works which were produced after his unhappy deafness had increased to such an extent that he could not possibly have heard any one of them—is boundless. In every composition we find a hundred combinations; all perfectly distinct from one another, yet all tending, in spite of their infinite variety, to the same harmonious result; and all wrought out, with indefatigable care, in places which many less conscientious authors would have passed over as of comparatively little importance such, for instance, as the two or three concluding bars of the slow movement of the Pastoral Symphony (No 6, in F)—