from Pergolesi; in which the melody passing from note to note of the chord of F minor touches the discordant notes G, B, D, and E in passing.

Equally simple are the passing notes which are arrived at by going from an essential note of harmony to its next neighbour in the degrees of the scale on either side and back again, as in the following example from Handel.

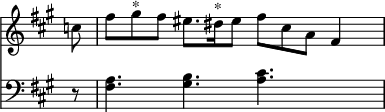

The remaining simple form is the insertion of notes melodically between notes of different chords, as (a). In modern music notes are used chromatically in the same ways, as (b).

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative d'' { \cadenzaOn << { d16^"(a)"[ c^"*"] b4 \bar "||" <d f>16^"(b)"[ fis g gis] a[ ais b c] \bar "|" <cis a>4 } \\ { fis,,8 g4 | a16 s8. <d f>16 s8. <e a,>4 } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/h/s/hs9bitxo9ek9g8qajt422hbznfx8417/hs9bitxo.png)

It would appear from such simple principles that passing notes must always be continuous from point to point; but the early masters of the polyphonic school soon found out devices for diversifying this order. The most conspicuous of these was the process of interpolating a note between the passing note and the arrival at its destination, as in the following example from Josquin des Prés—

in which the passing note E which lies properly between F and D is momentarily interrupted in its progress by the C on the other side of D being taken first. This became in time a stereotyped formula, with curious results which are mentioned in the article Harmony [vol. i. p. 678]. Another common device was that of keeping the motion of sounds going by taking the notes on each side of a harmony note in succession as

![{ \time 2/8 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative c'' << { c16[ b^"*" d^"*" c] \bar "||" g[ a^"*" fis^"*" g] \bar "||" } \\ { <e c>4 q } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/1/q1n2gikvblma9lfgr7bhyq5fz6gfmcf/q1n2gikv.png)

which is also a sufficiently common form in modern music.

A developed form which combines chromatic passing notes to a point with a leap beyond, before the point is taken, is the following from Weber's Oberon, which is curious and characteristic.

A large proportion of passing notes fall upon the unaccented portions of the bar, but powerful effects are obtained by reversing this and heavily accenting them: two examples are given in the article Harmony [vol. i. p. 683] and a curious example where they are daringly mixed up in a variety of ways may be noted in the first few bars of No. 5 of Brahms's Clavier-Stücke, Op. 76. Some writers classify as passing notes those which are taken preparatorily a semitone below a harmony note in any position, as in the following example—

![{ \time 3/8 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.TupletNumber #'stencil = ##f \override Score.TupletBracket #'bracket-visibility = ##f << \new Staff { \key g \major \partial 4 \relative d'' { \repeat unfold 4 { \times 2/3 { d16[ bes g] } } } }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key g \major \relative c' { \times 2/3 { s8 cis16_"*" } d[ a_"*"] | bes[ fis_"*" g8] } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/6/r/6r04us89e4xhsi0k3450ocpjpmuivq7/6r04us89.png)

etc.

For further examples of their use in combination and in contrary motion etc., see Harmony.

[ C. H. H. P. ]

PASSION MUSIC (Lat. Cantus Passionis Domini noslri Jesu Christi; Germ. Passions Musik). The history of the Passion of our Lord has formed part of the Service for Holy Week in every part of Christendom from time immemorial: and though, no doubt, the all-important Chapters of the Gospel in which it is contained were originally read in the ordinary tone of voice, without any attempt at musical recitation, there is evidence enough to prove that the custom of singing it to a peculiar Chaunt was introduced at a very early period into the Eastern as well as into the Western Church.

S. Gregory Nazianzen, who flourished between the years 330 and 390, seems to have been the first Ecclesiastic who entertained the idea of setting forth the History of the Passion in a dramatic form. He treated it as the Greek Poets treated their Tragedies, adapting the Dialogue to a certain sort of chaunted Recitation, and interspersing it with Choruses disposed like those of Æschylus and Sophocles. It is much to be regretted that we no longer possess the Music to which this early version was sung; for a careful examination of even the smallest fragments of it would set many vexed questions at rest. But all we know is, that the Sacred Drama really was sung throughout. [See pp. 497–498 of the present volume.]

In the Western Church the oldest known 'Cantus Passionis' is a solemn Plain Chaunt Melody, the date of which it is absolutely impossible to ascertain. As there can be no doubt that it was, in the first instance, transmitted from generation to generation by tradition only, it is quite possible that it may have undergone changes in early times; but so much care was taken in the 16th century to restore it to its