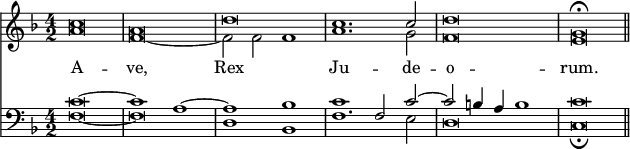

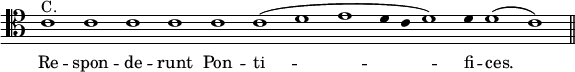

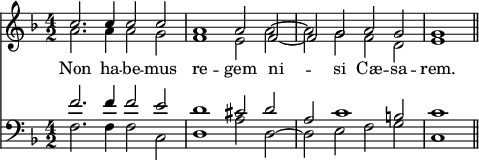

dramatic form; and the treatment required by the two forms is essentially different. Mendelssohn would have embodied the words, 'Crucify Him! crucify Him!' in a raging Chorus, like his own 'Stone him to death.' Vittoria sets them before us as they would have been reported by a weeping narrator, overwhelmed with sorrow at their cruelty; a narrator whose tone would have been all the more tearful in proportion to the sincerity of his affliction. Surely this is the way in which they should be sung to us in Holy Week. The object of singing the Passion is, to lead men to meditate upon it; not to divert their minds by a dramatic representation. And in this sense Vittoria has succeeded to perfection, as even the few subjoined extracts from his 'Passion according to S. John' will suffice to prove.

Francesco Suriano also brought out a polyphonic rendering of the exclamations of the Crowd, with harmonies which were certainly very beautiful, though they want the deep feeling which forms the most noticeable feature in Vittoria's settings, and, doubtless for that reason, have never attained an equal degree of celebrity. Vittoria's 'Passion' was first printed at Rome by Alessandro Gardano in 1585; and the first and last portions of it—the versions of S. Matthew and S. John—were published some years ago by R. Butler, 6 Hand Court, High Holborn, in a cheap edition which is no doubt still attainable. The entire work of Suriano will be found in Proske's 'Musica Divina,' vol. iv.

But it was not only with a view to its introduction into an Ecclesiastical Function that the Story of our Lord's Passion was set to Music. We find it in the Middle Ages selected as a constant and never-tiring theme for those Mysteries and Miracle Plays by means of which the history of the Christian Faith was disseminated among the people before they were able to read it for themselves. Some valuable reliques of the Music adapted to these antient versions of the Story are still preserved to us. An interesting example taken from a French 'Mystery of the Passion,' dating as far back as the 14th century, will be found at page 533 of the present volume. Fontenelle[1] speaks of a 'Mystery of the Passion' produced by a certain Bishop of Angers in the middle of the 15th century, with so much Music of a really dramatic character, that it might almost be described as a Lyric Drama. In this primitive work we first find the germ of an idea which Mendelssohn has used with striking effect in his Oratorio 'S.Paul.' [See Oratorio, p. 555.] After the Baptism of our Saviour, God the Father speaks; and it is recommended that His words 'should be pronounced very audibly and distinctly by three Voices at once, Treble, Alto, and Bass, all well in tune; and in this Harmony the whole Scene which follows should be sung.' Here then we have the first idea of the 'Passion Oratorio,' which however was not developed directly from it, but followed a somewhat circuitous course, adopting certain characteristics peculiar to the Mystery, together with certain others belonging to the Ecclesiastical 'Cantus Passionis' already described, and mingling these distinct though not discordant elements in such a manner as to produce eventually a form of Art, the wonderful beauty of which has rendered it immortal.

In the year 1573 a German version of the Passion was printed at Wittenberg, with Music for the Recitation and Choruses-introductory and final—in four parts. Bartholomäus Gese enlarged upon this plan, and produced, in 1588, a work in which our Lord's words are set for four Voices, those of the Crowd for five, those of S. Peter and Pontius Pilate for three, and those of the Maid Servant for two. In the next century Heinrich Schütz set to Music the several Narratives of each of the four Evangelists, making extensive use of the Melodies of the innumerable Chorales which were, at that period, more popular in Germany than any other kind of Sacred Music, and skilfully working them up into very elaborate Choruses. He did not, however, venture entirely to exclude the Ecclesiastical Plain Chaunt. In his work, as in all those that had preceded it, the venerable Melody was still retained in those portions of the narrative which were adapted to simple Recitative—or at least in those sung by the Evangelist—the Chorale being only introduced in the harmonised passages. But in 1672 Johann Sebastiani made a bolder experiment, and produced at Königsberg a 'Passion' in which the Recitatives were set

- ↑ Hist. du Theatre Française.