effects at the command of a composer. Handel often introduces a pause with prodigious effect before the last phrase of a chorus, as in 'Then round about the starry throne,' and many another case. Instances of the effect of the pause may be found in the delay on the last note of each line of the chorales of the German church, which is happily imitated by Mendelssohn in several of the Organ Sonatas, and in other places, where, though no pause actually occurs, and the strict time is kept up, the effect is produced by bringing in the next line of the chorale a bar or more late. Beethoven had a peculiarly effective way of introducing pauses in the first giving out of the principal subject of the movement, and so giving a feeling of suspense, as in the first movement of the Symphony No. 5 in C minor, the beginning of the last movement of the Pianoforte Trio, Op. 70, No. 1, etc. Pauses at the end of a movement, over a rest, or even over a silent bar, are intended to give a short breathing-space before going on to the next movement. They are then exactly the reverse of the direction 'attacca' [for which see vol. i. p. 100b ]. 'Pause' is the title of the last but one of the pieces in Schumann's 'Carneval,' and is an excerpt of 27 bars long from the Préambule to the whole, acting as a sort of prelude to the Marche des Davidsbündler contre les Philistins.' 'Pause' is also the title of a fine song in Schubert's 'Schöne Müllerin.'

[ J. A. F. M. ]

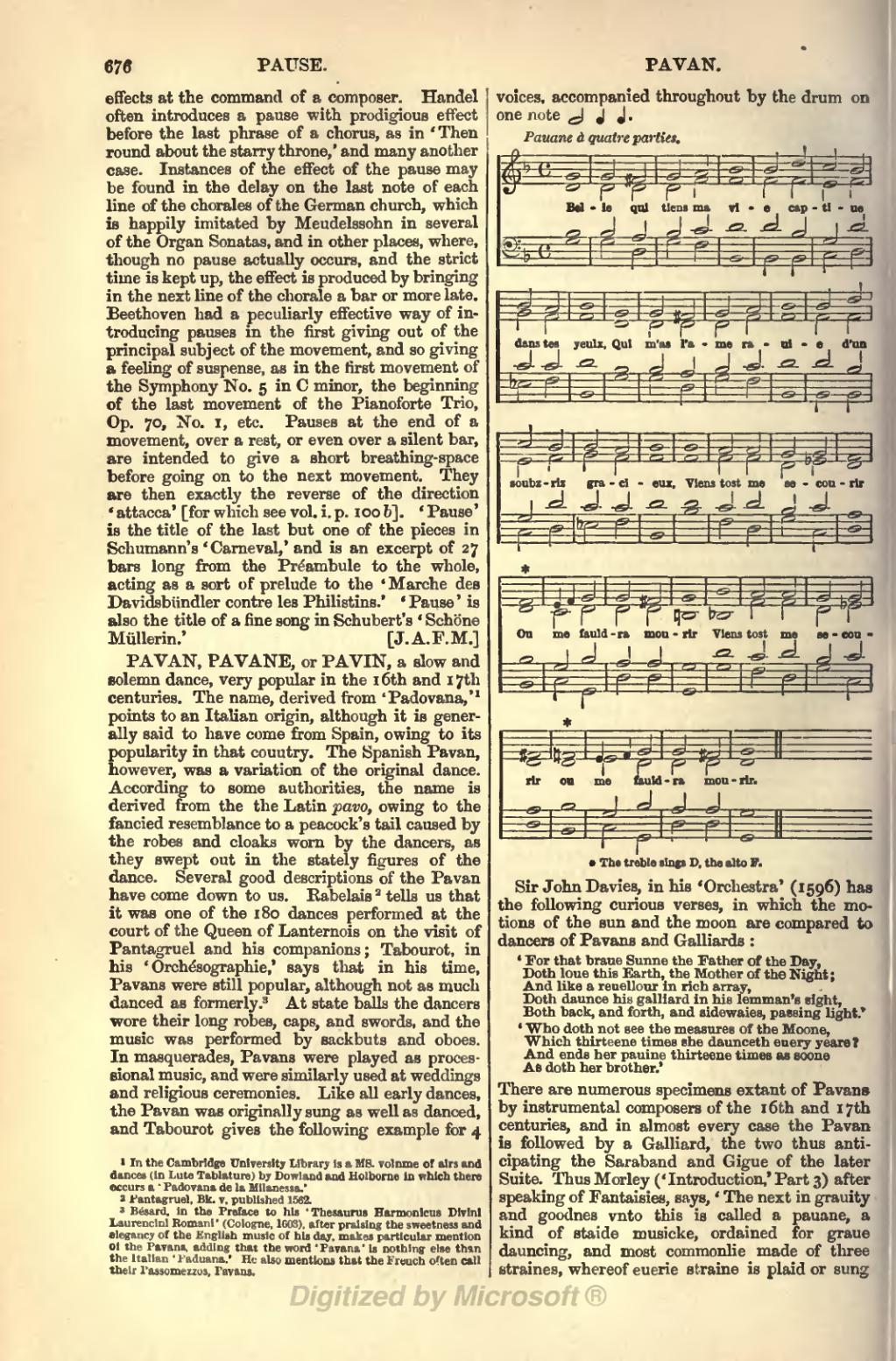

PAVAN, PAVANE, or PAVIN, a slow and solemn dance, very popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. The name, derived from 'Padovana,'[1] points to an Italian origin, although it is generally said to have come from Spain, owing to its popularity in that country. The Spanish Pavan, however, was a variation of the original dance. According to some authorities, the name is derived from the the Latin pavo, owing to the fancied resemblance to a peacock's tail caused by the robes and cloaks worn by the dancers, as they swept out in the stately figures of the dance. Several good descriptions of the Pavan have come down to us. Rabelais[2] tells us that it was one of the 180 dances performed at the court of the Queen of Lanternois on the visit of Pantagruel and his companions; Tabourot, in his 'Orchésographie,' says that in his time, Pavans were still popular, although not as much danced as formerly.[3] At state balls the dancers wore their long robes, caps, and swords, and the music was performed by sackbuts and oboes. In masquerades, Pavans were played as processional music, and were similarly used at weddings and religious ceremonies. Like all early dances, the Pavan was originally sung as well as danced, and Tabourot gives the following example for 4 voices, accompanied throughout by the drum or one note

.

*The treble sings D, the alto F.

Sir John Davies, in his 'Orchestra' (1596) has the following curious verses, in which the motions of the sun and the moon are compared to dancers of Pavans and Galliards:

'For that braue Sunne the Father of the Day,

Doth loue this Earth, the Mother of the Night;

And like a reuellour in rich array,

Doth daunce his galliard in his lemman's sight,

Both back, and forth, and sidewaies, passing light.'

'Who doth not see the measures of the Moone,

Which thirteene times she dannceth euery yeare?

And ends her pauine thirteene times as soone

As doth her brother.'

There are numerous specimens extant of Pavans by instrumental composers of the 16th and 17th centuries, and in almost every case the Pavan is followed by a Galliard, the two thus anticipating the Saraband and Gigue of the later Suite. Thus Morley ('Introduction,' Part 3) after speaking of Fantaisies, says, 'The next in grauity and goodnes vnto this is called a pauane, a kind of staide musicke, ordained for grau dauncing, and most commonlie made of thr straines, whereof euerie straine is plaid or sung

- ↑ In the Cambridge University Library is a MS. volume of airs and dances (in Lute Tablature) by Dowland and Holborne in which there occurs a 'Padovana de la Milanessa.'

- ↑ Pantagruel, Bk. v, published 1562.

- ↑ Bésard, in the Preface to his 'Thesaurus Harmonious Divini Laurencini Romani' (Cologne, 1608), after praising the sweetness and elegancy of the English music of his day, makes particular mention ol the Pavans, adding that the word 'Pavana' is nothing else than the Italian 'Paduana.' He also mentions that the French often call their Passomezzos, Pavans.