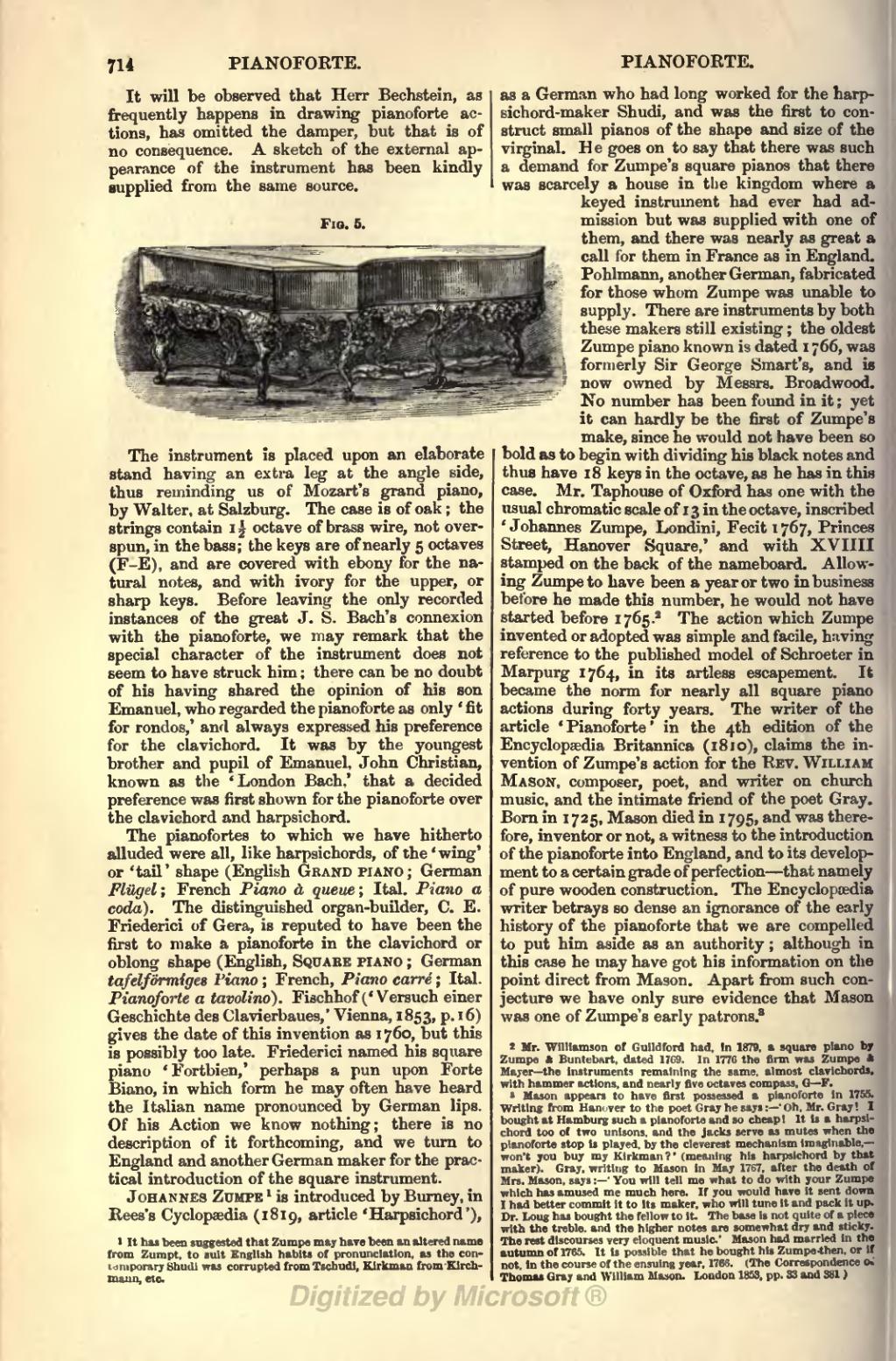

It will be observed that Herr Bechstein, as frequently happens in drawing pianoforte actions, has omitted the damper, but that is of no consequence. A sketch of the external appearance of the instrument has been kindly supplied from the same source.

Fig. 5.

The instrument is placed upon an elaborate stand having an extra leg at the angle side, thus reminding us of Mozart's grand piano, by Walter, at Salzburg. The case is of oak; the strings contain 1½ octave of brass wire, not overspun, in the bass; the keys are of nearly 5 octaves (F–E), and are covered with ebony for the natural notes, and with ivory for the upper, or sharp keys. Before leaving the only recorded instances of the great J. S. Bach's connexion with the pianoforte, we may remark that the special character of the instrument does not seem to have struck him; there can be no doubt of his having shared the opinion of his son Emanuel, who regarded the pianoforte as only 'fit for rondos,' and always expressed his preference for the clavichord. It was by the youngest brother and pupil of Emanuel, John Christian, known as the 'London Bach,' that a decided preference was first shown for the pianoforte over the clavichord and harpsichord.

The pianofortes to which we have hitherto alluded were all, like harpsichords, of the 'wing' or 'tail' shape (English Grand Piano; German Flügel; French Piano à queue; Ital. Piano a coda). The distinguished organ-builder, C. E. Friederici of Gera, is reputed to have been the first to make a pianoforte in the clavichord or oblong shape (English, Square Piano; German tafelförmiges Piano; French, Piano carré; Ital. Pianoforte a tavolino). Fischhof ('Versuch einer Geschichte des Clavierbaues,' Vienna, 1853, p. 16) gives the date of this invention as 1760, but this is possibly too late. Friederici named his square piano 'Fortbien,' perhaps a pun upon Forte Biano, in which form he may often have heard the Italian name pronounced by German lips. Of his Action we know nothing; there is no description of it forthcoming, and we turn to England and another German maker for the practical introduction of the square instrument.

Johannes Zumpe[1] is introduced by Burney, in Rees's Cyclopaedia (1819, article 'Harpsichord'), as a German who had long worked for the harpsichord-maker Shudi, and was the first to construct small pianos of the shape and size of the virginal. He goes on to say that there was such a demand for Zumpe's square pianos that there was scarcely a house in the kingdom where a keyed instrument had ever had admission but was supplied with one of them, and there was nearly as great a call for them in France as in England. Pohlmann, another German, fabricated for those whom Zumpe was unable to supply. There are instruments by both these makers still existing; the oldest Zumpe piano known is dated 1766, was formerly Sir George Smart's, and is now owned by Messrs. Broadwood. No number has been found in it; yet it can hardly be the first of Zumpe's make, since he would not have been so bold as to begin with dividing his black notes and thus have 18 keys in the octave, as he has in this case. Mr. Taphouse of Oxford has one with the usual chromatic scale of 13 in the octave, inscribed 'Johannes Zumpe, Londini, Fecit 1767, Princes Street, Hanover Square,' and with XVIIII stamped on the back of the nameboard. Allowing Zumpe to have been a year or two in business before he made this number, he would not have started before 1765.[2] The action which Zumpe invented or adopted was simple and facile, having reference to the published model of Schroeter in Marpurg 1764, in its artless escapement. It became the norm for nearly all square piano actions during forty years. The writer of the article 'Pianoforte' in the 4th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica (1810), claims the invention of Zumpe's action for the Rev. William Mason, composer, poet, and writer on church music, and the intimate friend of the poet Gray. Born in 1725, Mason died in 1795, and was therefore, inventor or not, a witness to the introduction of the pianoforte into England, and to its development to a certain grade of perfection—that namely of pure wooden construction. The Encyclopædia writer betrays so dense an ignorance of the early history of the pianoforte that we are compelled to put him aside as an authority; although in this case he may have got his information on the point direct from Mason. Apart from such conjecture we have only sure evidence that Mason was one of Zumpe's early patrons.[3]

- ↑ It has been suggested that Zumpe may have been an altered name from Zumpt, to suit English habits of pronunciation, as the contemporary Shudi was corrupted from Tschudi, Kirkman from Kirchmann, etc.

- ↑ Mr. Williamson of Guildford had, in 1879, a square piano by Zumpe & Buntebart, dated 1769. In 1776 the firm was Zumpe & Mayer—the instruments remaining the same, almost clavichords with hammer actions, and nearly five octaves compass, G–F.

- ↑ Mason appears to have first possessed a pianoforte in 1755. Writing from Hanover to the poet Gray he says:—'Oh, Mr. Gray! I bought at Hamburg such a pianoforte and so cheap! It is a harpsichord too of two unisons, and the jacks serve as mutes when pianoforte stop is played, by the cleverest mechanism imaginable,—won't you buy my Kirkman?' (meaning his harpsichord by that maker). Gray, writing to Mason in May 1767, after the death of Mrs. Mason, says:—'You will tell me what to do with your Zumpe which has amused me much here. If you would have it sent down I had better commit it to its maker, who will tune it and pack it up. Dr. Long has bought the fellow to it. The base is not quite of a piece with the treble, and the higher notes are somewhat dry and sticky. The rest discourses very eloquent music.' Mason had married in the autumn of 1765. It is possible that he bought his Zumpe then, or if not, in the course of the ensuing year, 1765. (The Correspondence of Thomas Gray and William Mason. London 1853, pp. 33 and 381.)