the 'Hostias.' The collection of 'Urschriften,' therefore, needed only the original autographs of the 'Requiem' and 'Kyrie,' to render it complete. These MSS, alone, would have been a priceless acquisition; but, in 1838, the same Library was still farther enriched by the purchase, for 50 ducats, of the complete MS. originally sold to Count von Walsegg; and it is now conclusively proved that the 'Requiem' and 'Kyrie,' with which this MS. begins, are the original autographs needed to complete the collection of 'Urschriften'; and, that the remainder of the work is entirely in the hand-writing of Süssmayer. It is, therefore, quite certain, that, whatever else he may have effected, Süssmayer did not furnish the Instrumentation of the 'Requiem' and 'Kyrie,' as he claims to have done.[1]

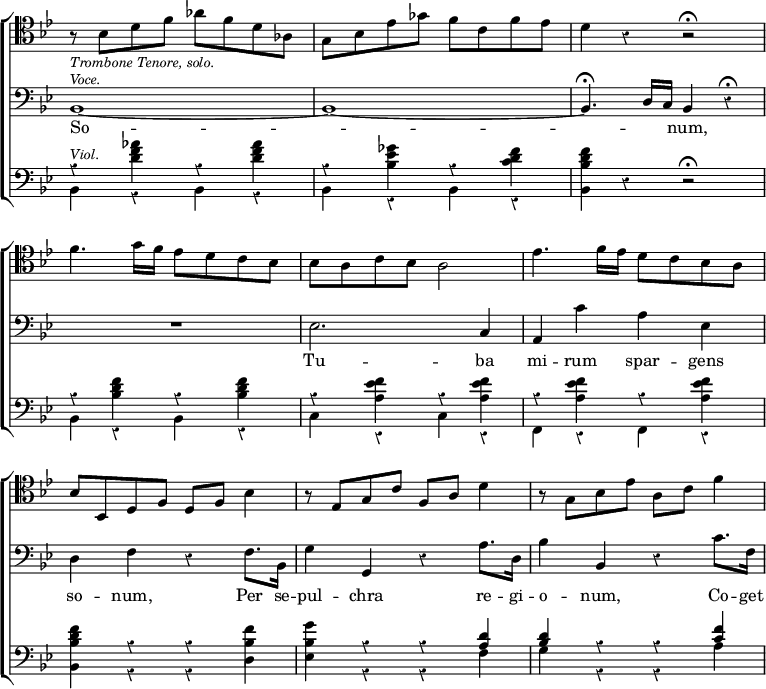

In criticising the merits of the Requiem as a work of Art, it is necessary to weigh the import of these now well-ascertained facts, very carefully indeed, against the internal evidence afforded by the Score itself. The strength of this evidence has not, we think, received, as yet, full recognition. Gottfried Weber, dazzled, perhaps, by the hypothetic excellence of another Requiem of his own production, roundly abused the entire Composition, which he described as a disgrace to the name of Mozart. Few other Musicians would venture to adopt this view; though many have taken exception to certain features in the Instrumentation more especially, some Trombone passages in the 'Tuba mirum' and 'Benedictus'—even, in one case, to the extent of doubting whether they may not have been purposely introduced, as a mask, 'to screen the fraud of an impostor.' Yet, strange to say, e first of these very passages stands, in the Vienna MS. in Mozart's own handwriting.[2]

Such passages as these, though they may, perhaps, strengthen Süssmayer's claim to have filled in certain parts of the Instrumentation, stand on a very different ground to those which concern the Composition of whole Movements. The 'Lacrymosa' is, quite certainly, one of the most beautiful Movements in the whole Requiem—and Mozart is credited with having only finished the first 8 bars of it! Yet it is impossible to study this movement, carefully, without arriving at Professor Macfarren's conclusion, that 'the whole was the work of one mind, which mind was Mozart's. Süssmayer may have written it out, perhaps; but it must have been from the recollection of what Mozart had played, or sung to him; for, we know that this very Movement occupied the dying Composer's attention, almost to the last moment of his life. In like manner, Mozart may have left no 'Urschriften' of the 'Sanctus,' 'Benedictus,' and 'Agnus Dei'—though the fact that they have never been discovered does not prove that they never existed—and yet he may have played and sung these Movements often enough to have given Süssmayer a very clear idea of what he intended to write. We must either believe that he did this, or that Süssmayer was as great a genius as he; for not one of Mozart's acknowledged Masses will bear comparison with the Requiem, either as a work of Art, or the expression of a devout religious feeling. In this respect, it stands almost alone among Instrumental Masses, which nearly always sacrifice religious feeling to technical display.

(2.) Next in importance to Mozart's immortal work are the two great Requiem Masses of Cherubini. The first of these, in C minor, was written for the Anniversary of the death of King Louis XVI. (Jan. 21, 1793), and first sung, on that occasion, at the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis, in 1817; after which it was not again heard until Feb. 14, 1820, when it was repeated, in the same Church, at the Funeral of the Duc de Berri. Berlioz regarded this as Cherubini's greatest work. It is undoubtedly full of beauties. Its general tone is one of extreme mournfulness, pervaded, throughout, by deep religious feeling. Except in the 'Dies iræ' and 'Sanctus' this style is never exchanged for a more excited one; and, even then, the treatment can scarcely be called dramatic. The deep pathos of the little Movement, interposed after the last 'Osanna,' to fulfil the usual office of the 'Benedictus'—which is here incorporated with the 'Sanctus'—exhibits the Composer's power of appealing to the feelings in its most affecting light.

- ↑ The full details of the remarkable history, which we have here given in the form of a very rapid sketch, will be found in a delightful little brochure, entitled 'The Story of Mozart's Requiem,' by William Pole, F.R.S., Mus. Doc., Oxon. (Novello & Co.)

- ↑ We make this statement on the authority of Messrs. Breitkopf & Härtel's latest Score, having had no opportunity of verifying it, by comparison with the original MS., before going to press.